TEXTILES and the MAYA ARCHAEOLOGICAL RECORD Gender, Power, and Status in Classic Period Caracol, Belize

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

What Maya Collapse? Terminal Classic Variation in the Maya Lowlands

J Archaeol Res (2007) 15:329–377 DOI 10.1007/s10814-007-9015-x ORIGINAL PAPER What Maya Collapse? Terminal Classic Variation in the Maya Lowlands James J. Aimers Published online: 17 August 2007 Ó Springer Science+Business Media, LLC 2007 Abstract Interest in the lowland Maya collapse is stronger than ever, and there are now hundreds of studies that focus on the era from approximately A.D. 750 to A.D. 1050. In the past, scholars have tended to generalize explanations of the collapse from individual sites and regions to the lowlands as a whole. More recent approaches stress the great diversity of changes that occurred across the lowlands during the Terminal Classic and Early Postclassic periods. Thus, there is now a consensus that Maya civilization as a whole did not collapse, although many zones did experience profound change. Keywords Maya Á Collapse Á Terminal Classic–Early Postclassic Introduction ‘‘Much has been published in recent years about the collapse of Maya civilization and its causes. It might be wise to preface this chapter with a simple statement that in my belief no such thing happened’’ (Andrews IV 1973, p. 243). More than three decades after Andrews made this statement, interest in the lowland Maya collapse is more intense than ever. Of the more than 400 books, chapters, or articles of which I am aware, over half were published in the last ten years. As always, speculation about the collapse follows contemporary trends (Wilk 1985), and widespread concern over war and the physical environment have made the lowland Maya into a cautionary tale for many (Diamond 2005; Gibson 2006; J. -

2 0 2 0–2 0 2 1 T R Av E L B R O C H U

2020–2021 R R ES E VE O BROCHURE NL INEAT VEL A NATGEOEXPE R T DI T IO NS.COM NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC EXPEDITIONS NORTH AMERICA EURASIA 11 Alaska: Denali to Kenai Fjords 34 Trans-Siberian Rail Expedition 12 Canadian Rockies by Rail and Trail 36 Georgia and Armenia: Crossroads of Continents 13 Winter Wildlife in Yellowstone 14 Yellowstone and Grand Teton National Parks EUROPE 15 Grand Canyon, Bryce, and Zion 38 Norway’s Trains and Fjords National Parks 39 Iceland: Volcanoes, Glaciers, and Whales 16 Belize and Tikal Private Expedition 40 Ireland: Tales and Treasures of the Emerald Isle 41 Italy: Renaissance Cities and Tuscan Life SOUTH AMERICA 42 Swiss Trains and the Italian Lake District 17 Peru Private Expedition 44 Human Origins: Southwest France and 18 Ecuador Private Expedition Northern Spain 19 Exploring Patagonia 45 Greece: Wonders of an Ancient Empire 21 Patagonia Private Expedition 46 Greek Isles Private Expedition AUSTRALIA AND THE PACIFIC ASIA 22 Australia Private Expedition 47 Japan Private Expedition 48 Inside Japan 50 China: Imperial Treasures and Natural Wonders AFRICA 52 China Private Expedition 23 The Great Apes of Uganda and Rwanda 53 Bhutan: Kingdom in the Clouds 24 Tanzania Private Expedition 55 Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia: 25 On Safari: Tanzania’s Great Migration Treasures of Indochina 27 Southern Africa Safari by Private Air 29 Madagascar Private Expedition 30 Morocco: Legendary Cities and the Sahara RESOURCES AND MORE 31 Morocco Private Expedition 3 Discover the National Geographic Difference MIDDLE EAST 8 All the Ways to Travel with National Geographic 32 The Holy Land: Past, Present, and Future 2 +31 (0) 23 205 10 10 | TRAVELWITHNATGEO.COM For more than 130 years, we’ve sent our explorers across continents and into remote cultures, down to the oceans’ depths, and up the highest mountains, in an effort to better understand the world and our relationship to it. -

Itinerary & Program

Overview Explore Belize in Central America in all of its natural beauty while embarking on incredible tropical adventures. Over nine days, this tour will explore beautiful rainforests, Mayan ruins and archeology, and islands of this tropical paradise. Some highlights include an amazing tour of the Actun Tunichil Muknal (“Cave of the Crystal Maiden”), also known at ATM cave; snorkeling the second largest barrier reef in the world, the critically endangered Mesoamerican Barrier Reef, at the tropical paradise of South Water Caye; touring Xunantunich Mayan ruin (“Sculpture of Lady”); and enjoying a boat ride on the New River to the remote Mayan village of Lamanai. Throughout this tour, we’ll have the expertise of Luis Godoy from Belize Nature Travel, a native Mayan and one of Belize’s premier licensed guides, to lead us on some amazing excursions and share in Belize’s heritage. We’ll also stay at locally owned hotels and resorts and dine at local restaurants so we can truly experience the warm and welcoming culture of Belize. UWSP Adventure Tours leaders Sue and Don Kissinger are ready to return to Belize to share the many experiences and adventures they’ve had in this beautiful country over the years. If you ask Sue if this is the perfect adventure travel opportunity for you she’ll say, “If you have an adventurous spirit, YOU BETTER BELIZE IT!” Tour Leaders Sue and Don Kissinger Sue and Don have travelled extensively throughout the United States, Canada, Central America, Africa and Europe. They met 36 years ago as UW-Stevens Point students on an international trip and just celebrated their 34th wedding anniversary. -

The Political Appropriation of Caves in the Upper Belize Valley

APPROVAL PAGE FOR GRADUATE THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF REQUIREMENTS FOR DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS AT CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, LOS ANGELES BY Michael J. Mirro Candidate Anthropology Field of Concentration TITLE: The Political Appropriation of Caves in the Upper Belize Valley APPROVED: Dr. James E. Brady Faculty Member Signature Dr. Patricia Martz Faculty Member Signature Dr. Norman Klein Faculty Member Signature Dr. ChorSwang Ngin Department Chairperson Signature DATE___________________ THE POLITICAL APPROPRIATION OF CAVES IN THE UPPER BELIZE VALLEY A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of Anthropology California State University, Los Angeles In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts By Michael J. Mirro December 2007 © 2007 Michael J. Mirro ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First, I would like to thank Jaime Awe, of the Department of Archaeology in Belmopan, Belize for providing me with the research opportunities in Belize, and specifically, allowing me to co-direct research at Barton Creek Cave. Thank you Jaime for sending Vanessa and I to Actun Tunichil Muknal in the summer of 1996; that one trip changed my life forever. Thank you Dr. James Brady for guiding me through the process of completing the thesis and for you endless patience over the last four years. I appreciate all the time and effort above and beyond the call of duty that you invested in assisting me. I would specifically like to thank Reiko Ishihara and Christophe Helmke for teaching me the ins-and-outs of Maya ceramics and spending countless hours with me classifying sherds. Without your help, I would never have had enough data to write this thesis. -

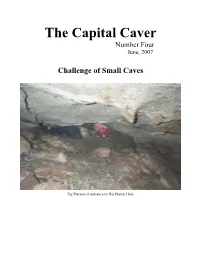

The Capital Caver Number Four June, 2007

The Capital Caver Number Four June, 2007 Challenge of Small Caves Saj Pierson in entrance to Hackberry Hole The Capital Caver Number 4 The Capital Caver is published very irregularly by the Texas Cave Management Association (TCMA) to inform TCMA members about issues involving Texas caves and karst. This issue of the Capital Caver contains an editorial to remind cavers that by no means have all Texas Caves been discovered. There are many more caves still to be found, and many sections of known caves have not been well checked. Then the relatively unstudied biology of the Barton Springs Segment of the Edwards Aquifer is considered, and the Barton Springs Segment is divided into four potential habitat zones based on food energy input and aquifer characteristics. The principal concern of this issue is how to report and compile cave information. In the past the TSS has provided information on all caves in a relatively large area through printed reports. But, advances in digital publishing and distribution have made other options attractive, and these alternatives are examined. The issues examined in the Capital Caver are the responsibility of the editor, and the opinions expressed are the responsibility of the authors of the individual articles, and do not necessarily represent the opinions or concerns of the Texas Cave Management Association. Unsigned articles are the responsibility of the editor. Material in the Capital Caver is not reviewed or authorized by the TCMA. Table of Contents Exploration and Caving . 2 Habitat Zones in the Barton Springs Segment of the Edwards Aquifer. 3 Caver FAQ's . -

Arrival Belize/ San Ignacio 5 Nights Options, Such As Actun Tunichil Muknal (Challenging, the Arrival Belize International Airport

water cave system in a canoe equipped with a powerful spotlight. While canoeing through the cave, see large and colorful formations, skeletal remains and other cultural artifacts left behind by the Maya centuries ago. BLD DAY FOUR – Lamanai Ruins & River Cruise Getting to Lamanai Ruins is half the fun! After a comfortable highway drive, board a riverboat at Tower Hill Bridge and head up the New River. The river is lined with hardwood trees, orchids and bromeliads, and you might see dainty wading birds called jacanas lightly walking on lily pads, while elusive crocodiles bask in the morning sunlight. At the entrance to the New River Lagoon, the ruins of Lamanai (Maya for "Submerged Crocodile") rise into view. Embark on a jungle hike to visit the Temple of the Mask, one of the tallest Mayan pyramids; the stucco mask of the Sun God "Kinich Ahau"; and the Temple of the Jaguar Masks. These impressive sites appear to materialize out of the rainforest amid the chatter of birds and the haunting call of the howler monkeys. BLD DAY FIVE – Dia libre / options Enjoy a day at your resort, shop, explore the adjacent ruins of Cahal Pech ($5), or select (additional fee) from popular DAY ONE – Arrival Belize/ San Ignacio 5 nights options, such as Actun Tunichil Muknal (challenging, the Arrival Belize International Airport. Your Interact ultimate jungle and Maya cave adventure), Caracol ruins, zip- Representative will greet you in the airport lobby. Transfer to lining, river rafting, or horseback riding. Fees vary from $85 to the Maya Heartland via the Hummingbird Highway. -

Belize Tropical & Mayan Adventure

BELIZE TROPICAL & MAYAN ADVENTURE January 11-19, 2018 Tour Leaders: Sue & Don Kissinger Mayan Ruins at Lamanai (photo by Sue Kissinger) Overview Explore Belize, Central America in all of its natural beauty while embarking on incredible tropical adventures. Over nine days, this tour will explore beautiful rainforests, Mayan ruins and archeology, and islands of this tropical paradise. Some highlights include an amazing tour of the Actun Tunichil Muknal (ATM) cave, snorkeling the second largest barrier reef in the world at South Water Caye, cave tubing the Jaguar Paw Caves, an expedition to the Caracol Mayan Ruins, and a boat trip through the jungle to the remote Mayan village of Lamanai. Throughout this tour, we will have the expertise of Luis Godoy from Belize Nature Travel, a native Mayan and one of Belize’s premier licensed guides, to guide us on some amazing excursions and share in Belize’s heritage. We’ll also stay at locally-owned hotels and resorts and dine at local restaurants so we can truly experience the warm and welcoming culture of Belize. UWSP Adventure Tours leaders Sue & Don Kissinger are ready to return to Belize to share the many experiences and adventures they’ve had in this beautiful country over the years. If you ask Sue if this is the perfect adventure travel opportunity for you she’ll say, “If you have an adventurous spirit, YOU BETTER BELIZE IT!” Tour Itinerary Jan. 11 (Thursday) – Arrive in Paradise! Your adventure begins when you arrive at the Belize International Airport in Belize City where our guides will greet us and transfer the group to the Hotel De La Fuente, in Orange Walk Towne (35 miles from the airport or 1 hour drive). -

Understanding the Archaeology of a Maya Capital City Diane Z

Research Reports in Belizean Archaeology Volume 5 Archaeological Investigations in the Eastern Maya Lowlands: Papers of the 2007 Belize Archaeology Symposium Edited by John Morris, Sherilyne Jones, Jaime Awe and Christophe Helmke Institute of Archaeology National Institute of Culture and History Belmopan, Belize 2008 Editorial Board of the Institute of Archaeology, NICH John Morris, Sherilyne Jones, George Thompson, Jaime Awe and Christophe G.B. Helmke The Institute of Archaeology, Belmopan, Belize Jaime Awe, Director John Morris, Associate Director, Research and Education Brian Woodye, Associate Director, Parks Management George Thompson, Associate Director, Planning & Policy Management Sherilyne Jones, Research and Education Officer Cover design: Christophe Helmke Frontispiece: Postclassic Cao Modeled Diving God Figure from Santa Rita, Corozal Back cover: Postclassic Effigy Vessel from Lamanai (Photograph by Christophe Helmke). Layout and Graphic Design: Sherilyne Jones (Institute of Archaeology, Belize) George Thompson (Institute of Archaeology, Belize) Christophe G.B. Helmke (Københavns Universitet, Denmark) ISBN 978-976-8197-21-4 Copyright © 2008 Institute of Archaeology, National Institute of Culture and History, Belize. All rights reserved. Printed by Print Belize Limited. ii J. Morris et al. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We wish to express our sincerest thanks to every individual who contributed to the success of our fifth symposium, and to the subsequent publication of the scientific contributions that are contained in the fifth volume of the Research Reports in Belizean Archaeology. A special thanks to Print Belize and the staff for their efforts to have the Symposium Volume printed on time despite receiving the documents on very short notice. We extend a special thank you to all our 2007 sponsors: Belize Communication Services Limited, The Protected Areas Conservation Trust (PACT), Galen University and Belize Electric Company Limited (BECOL) for their financial support. -

Where Is Lowland Maya Archaeology Headed?

Journal of Archaeological Research, Vol. 3, No. L 1995 Where Is Lowland Maya Archaeology Headed? Joyce Marcus 1 This article isolates three important trends in Lowland Maya archaeology during the last decade: (1) increased use of the conjunctive approach, with renewed appreciation of context and provenience; (2) waning use of the label "unique" to describe the Maya; and (3) an effort to use the Lowland Maya as a case study in social evolution. KEY WORDS: Maya archaeology; conjunctive approach; direct historic approach. INTRODUCTION I have been asked to review the last decade of Lowland Maya ar- chaeology and discuss any major trends that can be discerned. The task presents numerous problems, not the least of which is the fact that one has little time to deliberate on data so newly produced. I also do not want to run the risk of extolling current research at the expense of that done by our predecessors. Finally, the volume of literature on Maya archaeology has been increasing so rapidly in recent years that one cannot hope to do more than cite a fraction of it. I have tried to compensate for this by in- cluding a 400-entry bibliography at the end of the review. At least three major trends can be seen in the last decade of Lowland Maya archaeology, and I organize my presentation around them. The first trend is a substantial increase in the integration of multiple lines of evi- dence-in effect, what Walter W. Taylor (t948) called "the conjunctive ap- proach" (Carmack and Weeks, 1981; Fash and Sharer, 1991, Marcus, 1983; Sabloff, 1990). -

Antiquity Lijiagou and the Earliest Pottery in Henan Province, China

Antiquity http://journals.cambridge.org/AQY Additional services for Antiquity: Email alerts: Click here Subscriptions: Click here Commercial reprints: Click here Terms of use : Click here Lijiagou and the earliest pottery in Henan Province, China Youping Wang, Songlin Zhang, Wanfa Gu, Songzhi Wang, Jianing He, Xiaohong Wu, Tongli Qu, Jingfang Zhao, Youcheng Chen and Ofer Bar-Yosef Antiquity / Volume 89 / Issue 344 / April 2015, pp 273 - 291 DOI: 10.15184/aqy.2015.2, Published online: 08 April 2015 Link to this article: http://journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S0003598X15000022 How to cite this article: Youping Wang, Songlin Zhang, Wanfa Gu, Songzhi Wang, Jianing He, Xiaohong Wu, Tongli Qu, Jingfang Zhao, Youcheng Chen and Ofer Bar-Yosef (2015). Lijiagou and the earliest pottery in Henan Province, China. Antiquity, 89, pp 273-291 doi:10.15184/aqy.2015.2 Request Permissions : Click here Downloaded from http://journals.cambridge.org/AQY, IP address: 129.234.252.65 on 09 Apr 2015 Lijiagou and the earliest pottery in Henan Province, China Youping Wang 1,∗, Songlin Zhang2,WanfaGu2, Songzhi Wang2, Jianing He1, Xiaohong Wu1, Tongli Qu1, Jingfang Zhao1, Youcheng Chen1 & Ofer Bar-Yosef3 Research 0 km 2000 It has long been believed that the earliest ceramics in the central plain of China N were produced by the Neolithic cultures of Jiahu 1 and Peiligang. Excavations at Lijiagou in Henan Province, dating to Beijing the ninth millennium BC, have, however, revealed evidence for the earlier production Lijiagou of pottery, probably on the eve of millet and wild rice cultivation in northern and southern China respectively. It is assumed that,asinotherregionssuchassouth- west Asia and South America, sedentism preceded incipient cultivation. -

Download (PDF)

CURICULA VITAE (Academic) NAME: Diane Zaino Chase DATE: December 2019 Vice President for Academic Innovation, Student Success, and Strategic Initiatives Claremont Graduate University 150 E. 10th Street Claremont, CA 91711 telephone: office: (909) 607-3306 e-mail: [email protected] web-site: http://www.caracol.org EDUCATION: 1982 PhD. in Anthropology, University of Pennsylvania Dissertation: SPATIAL AND TEMPORAL VARIABILITY IN POSTCLASSIC NORTHERN BELIZE, University Microfilms International No. 8307296. 1975 B.A. with Honors in Anthropology, University of Pennsylvania EMPLOYMENT HISTORY: Claremont Graduate University 2019-present: Vice President for Academic Innovation, Student Success, and Strategic Initiatives. University of Nevada, Las Vegas: Administrative Positions 2016-2019: Executive Vice President and Provost. University of Nevada, Las Vegas: Academic Positions 2016-2019: Professor, Department of Anthropology, College of Liberal Arts. University of Central Florida: Administrative Positions 2015-2016: Vice Provost, Academic Program Quality, Academic Affairs. 2014-2015: Executive Vice Provost, Academic Affairs. 2014 (4/1-7/31): Interim Provost and Vice President, Academic Affairs. 2010-2014: Executive Vice Provost, Academic Affairs. 2010 (7/1-7/30): Interim Provost and Vice President, Academic Affairs. 2008-2010: Vice Provost. Academic Affairs. 2007-2008: Associate Vice President (Planning and Evaluation), Academic Affairs. 2006-2007: Interim Chair, Department of Theater, College of Arts and Humanities. 2005-2007: Assistant Vice President (International and Interdisciplinary Studies), Academic Affairs. 2004-2005: Interim Asst. Vice President (International and Interdisciplinary Studies), Academic Affairs. 2003-2004: Interim Assistant Vice President (Interdisciplinary Programs), Academic Affairs. 2000-2003: Interdisciplinary Coordinator, Academic Affairs. University of Central Florida: Academic Positions 2006-2016(4/30): Pegasus Professor, Department of Anthropology, College of Sciences. -

Estimation of Quantitative Descriptors of Northeastern

Estimation of quantitative descriptors of northeastern Mediterranean karst behavior: multiparametric study and local validation of the Siou-Blanc massif (Toulon, France) Stéphane Binet, Jacques Mudry, Catherine Bertrand, Yves Guglielmi, René Cova To cite this version: Stéphane Binet, Jacques Mudry, Catherine Bertrand, Yves Guglielmi, René Cova. Estimation of quantitative descriptors of northeastern Mediterranean karst behavior: multiparametric study and local validation of the Siou-Blanc massif (Toulon, France). Hydrogeology Journal, Springer Verlag, 2006, 14 (7), pp.1107-1121. 10.1007/s10040-006-0044-1. insu-00617825 HAL Id: insu-00617825 https://hal-insu.archives-ouvertes.fr/insu-00617825 Submitted on 30 Aug 2011 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Estimation of quantitative descriptors of northeastern Mediterranean karst behavior: multiparametric study and local validation of the Siou-Blanc massif (Toulon, France) Stéphane Binet & Jacques Mudry & Catherine Bertrand & Yves Guglielmi & René Cova S. Binet ()) : J. Mudry : C. Bertrand EA2642 Géosciences, Déformation, Ecoulement, Transfert, Université of Franche- Comté, 16 route de Gray, 25030, Besancon, France e-mail: [email protected] e-mail: jacques.mudry@univ- fcomte.fr e-mail: [email protected] Y. Guglielmi Géosciences Azur, Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, Université Nice Sophia-Antipolis, 250 rue Albert Einstein, 06560, Valbonne, France e-mail: [email protected] R.