The Harp As a Symbol of Liminality in Tchaikovsky's the Nutcracker

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PCC Cat 20-21 Jan Changes-Without Highlights

PENSACOLA CHRISTIAN COLLEGER 2020 – 2021 CATA LO G PENSACOLA CHRISTIAN COLLEGE PENSACOLA 1 UNDERGRADUATE 2 – EMPOWERING CHRISTIAN LEADERS R TO INFLUENCE THE WORLD 20 CATALOG 37426101-2/20 AS Sophomores, Juniors, and Seniors, Come Experience PCC for Yourself at College Days! Nov. 18–20, 2020 • Mar. 24–26, 2021 • Apr. 7–9, 2021 Yes, you can come any time, but no other time is quite like College Days. You’ll get a glimpse of college academics as you visit classrooms and labs. You’ll find out what students are like as you stay in a resi- dence hall. You can go to special activities planned just for you. But that’s not all. Beyond that, you’ll experience chapel in the Crowne Centre, go to meals in the Four Winds or Varsity, and head to the Sports Center for rock climbing and more. That’s just a start of what you can do during College Days. When you’re done looking through these pages, you’ll know a good bit about PCC. But it’s not the same as being here! See for yourself what PCC is really like. Ask questions in person. And get a better idea if this is the next step God has for you. Find out more today at pcci.edu/CollegeDays or call 1-800-PCC-INFO, ext. 4, to reserve your spot. pcci.edu • [email protected] 1-800-PCC-INFO (722-4636) for new student admissions (850) 478-8496 for all other info. @ConnectPCC Pensacola Christian College @ConnectPCC PensacolaChristianCollege catalog available online at pcci.edu/Catalog PENSACOLA CHRISTIAN COLLEGER 1 UNDERGRADUATE 2 – 20 CATALOG CONTENTS General Information ............................... -

V13.N05-12.4.19X

Be sure to do your Holiday shopping with local merchants! Vol. Vol. 3, 13, No. No. 11 5 Published Every Other Published Wednesday Every Other Established Wednesday 2007 December 4 – December March 10 17, - 23, 2019 2010 City Council Member Christy Weir enjoying Thanksgiving with Jean. VUSD students help to feed hungry families. Ninth Annual Thanksgiving Aera Energy Outreach Dinner employees team The Elf Giveaway is something bigger than the by Jill Forman holidays. It started as a family dinner… The next year, the park folks asked up with Ventura Jeri and Joe Bendot, the residential their friends. Visit Ventura caretakers of Community Presbyterian And so the tradition was started. City staff and Church, had a Thanksgiving dinner for This year, close to 700 meals were is giving away their family in the Fellowship Hall ten served to anyone who came. Almost 100 students to feed years ago. volunteers set up, served, bussed tables, a host of The following year, they asked their washed dishes, socialized with the diners hungry families friends from the park to join them. Continued on page 15 Aera Energy teamed up with staff generous gifts from the City of Ventura to put the “giving” in Thanksgiving by providing by Visit Ventura 140 families from the City of Ventura Tis the season to think Elf! As in a full Thanksgiving meal with all the Visit Ventura’s Elf Giveaway, yes. But trimmings. also as in mischievous fun, lips-sealed For years the staff at the City of secrets, and the magical Big Picture too. Ventura and students from the Ventura Now through Christmas Day, Visit Unified school district. -

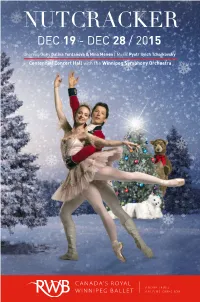

Nutcracker Dec 19 - Dec 28 / 2015

NUTCRACKER DEC 19 - DEC 28 / 2015 Choreography Galina Yordanova & Nina Menon | Music Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky Centennial Concert Hall with the Winnipeg Symphony Orchestra 1 VAL CANIPAROLI’S A CINDERELLA STORY FEB 17 - 21 / 2016 At the Centennial Concert Hall PHOTO: David PHOTO: A Cinderella Story A Cinderella Former Principal Dancers Vanessa Lawson (1997 – 2013) and Jaime Vargas (2004 - 2010) in the 2009 Production of (2004 - 2010) in the 2009 Production Lawson (1997 – 2013) and Jaime Vargas Vanessa Principal Dancers Former TICKETS FROM $29!* *plus applicable taxes & fees RWB.ORG 204.956.2792 TABLEAU Under the distinguished Patronage of His Excellency The Right Honourable David Johnston, C.C., C.M.M., C.O.M., C.D. Governor General of Canada founders: GWENETH LLOYD & BETTY FARRALLY artistic director emeritus: ARNOLD SPOHR, C.C., O.M. founding director, school professional division: DAVID MORONI, C.M. founding director, school recreational division: JEAN MACKENZIE artistic director executive director ANDRÉ LEWIS JEFF HERD Jo- Ann Sundermeier, Dmitri Dovgosolets artists PHOTO: Réjean Brandt Photography AMANDA GREEN SOPHIA LEE JO-ANN SUNDERMEIER DMITRI DOVGOSELETS LIANG XING ISSUE NO. 197 YAYOI BAN YOSUKE MINO To advertise in future issues of this program, call Larah Luna 204.957.3471 SARAH DAVEY ELIZABETH LAMONT ALANNA MCADIE TRISTAN DOBROWNEY KOSTYANTYN KESHYSHEV JOSH REYNOLDS COVER: EGOR ZDOR Jo-Ann Sundermier, Dmitri Dovgoselets PHOTO: Réjean Brandt Photography KATIE BONNELL JAIMI DELEAU YOSHIKO KAMIKUSA CHENXIN LIU ANNA O’CALLAGHAN MANAMI TSUBAI DESIGN: Aleli Estrada SARAH PO TING YEUNG LIAM CAINES TYLER CARVER STEPHAN POSSIN PRINTING: Dave’s Quick Print THIAGO DOS SANTOS LUZEMBERG SANTANA RYAN VETTER EDITOR: Larah Luna JESSE PETRIE SAEKA SHIRAI AMY YOUNG PHILIPPE LAROUCHE YUE SHI Royal Winnipeg Ballet is a chartered non-profit corporation operated by a voluntary Board of senior ballet master music director & conductor Directors, David Reid, Chair. -

Phoenix, 2004-01 Student Life

Governors State University OPUS Open Portal to University Scholarship Phoenix Student Newspapers 1-2004 Phoenix, 2004-01 Student Life Follow this and additional works at: http://opus.govst.edu/phoenix Recommended Citation Governors State University Student Life, Phoenix (2004, January). http://opus.govst.edu/phoenix/15 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Newspapers at OPUS Open Portal to University Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Phoenix by an authorized administrator of OPUS Open Portal to University Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ··--=========..-==::::----·~--=:::::::-·-------~-~-~---·---·----------·------------------···---·---·-------. ----·----·--------·-. ---·---~ nuary 200 . vo~um(~~ 3 IRsue :1 • I GSU ARCHIVES (:*lt . Senator Durbin Speaks on Funding for GSU Stephanie N. Blahut with The Library of Congress, in an effort for one year, as well as be required to attend Editor In Chief to educate teachers on using digital re sources within the classroom. It will also 45 hours of instruction Illinois Sen. Richard Durbin an link GSU and participating schools to The (on Saturdays and nounced that Governors State University Library of Congress's vast collection of during the summer). would be receiving government funding archives, reading materials, and other These are among a for the Adventures in the American Mind learning media. few of the details and (MM) program, during his speech in the "I want to make certain that we do criteria outlined in the university's library on Jan. 16, 2003. The this the right way; spend this money most MM program. program will se efficiently to train "Adventures of cure $335,000 the greatest the American Mind is over the next two number of a program that has years for GSU for teachers," said enjoyed great suc taking part in the Durbin in re cesses at other univer teaching and sponse to the sities in Illinois," said technology initia methods Con Durbin in a recent tive through The · gress will use to press release. -

Gavin D. Douglas Curriculum Vitae

Gavin D. Douglas Curriculum Vitae email: [email protected] Academic Position 2008-present Associate Professor, Ethnomusicology (Music Studies Dept. Head 2012-2016) UNC Greensboro. School of Music, Theatre and Dance 2002-2008 Assistant Professor, Ethnomusicology UNC Greensboro. School of Music Education 2001 PHD (Ethnomusicology) — University of Washington Dissertation: State Patronage of Burmese Traditional Music 1993 MMUS (Musicology/Ethnomusicology) — University of Texas at Austin Thesis: Popular Music in Canada: Globalism and the Struggle for National Identity 1991 BA (Philosophy) — Queen’s University 1990 BMUS (Performance Classical Guitar) — Queen’s University Publications (Books) 2010 Music in Mainland Southeast Asia: Experiencing Music Expressing Culture. New York, Oxford: Oxford University Press. Publications (Articles, peer reviewed) Forthcoming “Sound Authority in Burma,” in Sounds of Hierarchy and Power in Southeast Asia. Nathan Porath, ed. NIAS Press In Press ““Buddhist Soundscapes in Myanmar: Dhamma Instruments and Divine States of Consciousness.” Proceedings of the 4th Symposium of the ICTM Study Group on Performing Arts of Southeast Asia. Mohd Anis Md Nor and Patricia Matusky (eds.) Denpasar, Bali: Institut Seni Indonesia (ISI). In Press “Burma/Myanmar: History, Culture, Geography,” in The Sage Encyclopedia of Ethnomusicology, Janet Sturman J. and Geoffrey Golson, eds. In Press “Burma/Myanmar: Contemporary Performance Practice,” in The Sage Encyclopedia of Ethnomusicology, Janet Sturman and Geoffrey Golson, eds. 2015 “Buddhist -

Copyright 2010, Michigan Opera Theatre Copyright 2010, Michigan Opera Theatre the Official Magazine 1Sla of the Detroit Opera House ~~~Em~

Copyright 2010, Michigan Opera Theatre Copyright 2010, Michigan Opera Theatre The Official Magazine 1Sla of the Detroit Opera House ~~~eM~_---. Michigan Opera TheatreS 2000-2001 Season is lovingly dedicated to the memory of Lynn A. Townsend and Robert E. Dewar BRAVO IS A MICHIGAN OPERA THEATRE PUBLICATION Dr. David DiChiera, General Director Laura Wyss, Editor CONTRIBUTORS MICHIGAN OPERA THEATRE STAFF Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater Staff American Ballet Theatre Staff Arts'League of Michigan Staff Ballet Internationale Staff University Musical Society Staff PUBLISHER Live Publishing Company Frank Cucciarre, Design and Art Direction Chuck Rosenberg, Copy Editor Toby Faber, Director of Advertising Sales COVER PHOTO Detail from the Detroit Opera House, Mark]. Mancinelli, MJM Photography A special thanks to Jeanette Pawlaczyk and Bill Carroll Michigan Opera Theatre would like to thank Harmony House Records for donating season recordings and videos. Michigan Opera Theatre's 2000-2001 subscription and Single tickets have been graciously sponsored by Hunter House, Harmonie Park. METAL RESTORATION Physicians' service provided by Henry Ford Medical Center. Dent and scratcl-l. removal Re-a ttachmen t Alitalia is the official airline ~f Michigan Opera Theatre. • Sterling, brass, copper, bronze, and plate Pepsi-Cola is the official soft drink and juice provider for the Detroit Opera House. Starbucks Coffee is the official coffee of the Detroit Opera House. Ben Wearley, silversmith Steinway is the official piano of the Detroit Opera House and Michigan Opera Theatre. Steinway pianos are (248) 549-3016 provided by Hammel MuSiC, exclusive representative for Steinway and Sons in Michigan. President Tuxedo is the official provider of fonnal wear for the Detroit Opera House. -

Ad Pages Template

INCREASING OUR ALCOHOL TOLERANCE SINCE 1992 VOLUME 25 | ISSUE 48 | DECEMBER 1-7, 2016 | FREE HHealthealth IInsurancensurance vvs.s. PPenalty.enallttyy.. healthyheaallltthy cchoice.hoiicce. IIff youyou ddon’ton’t hhaveaavve hhealthealltth iinsurance,nsurance, yyouou ccouldould eendnd uupp payingpaayying eextraxtra mmoneyoney iinn ttaxax ppenalties,enalltties, whilewhile gettinggetting nnothingothing iinn rreturn.eturn. ButBut itit doesn’tdoesn’t havehaavve toto bebe tthathaatt wway.aayy. VisitVViisit bbeWellnm.comeeWWWeellnm.com andand browsebrowse a varietyvariety ofof hhealthealltth insuranceinsurance choices.choices. SomeSome mmayaayy costcost almostalmost thethe samesame asas payingpaayying thethe taxtaaxx ppenalty.enalltty. InIn fact,ffaact, somesome ppeopleeople areare payingpaayyyiing betweenbetween $50$50 andand $100$100 perper month.month. And,And, iinsteadnstead ofof gettinggetting nothing,nothing, youyou ccanan bebe coveredcovered ffoforoorr eeverythingverything fromffrrom preventativeprevennttaattiivve carecare ttoo peacepeace ofof mmind.ind. Real Life: The Chavez Family WithWith InsuranceInsurance WWiWithoutithouutt IInsurancensurance • PreventivePreventive CareCare • PrescriptionsPrescriptions • NONO benefitsbenefits • DDoctoroctor VVisitsisits • HHospitalospital sstaystays • NNOO ccoverageoverage • PPeaceeace ooff mmindind • SSpecialistpecialist visitsvisits • NNOO ppeaceeace ooff mmindind & ssoo mmuchuch mmore!ore! • HHigherigher PPricetagricetag Annual Cost: $2,053 Annual Cost: $2,085 ForFor ffullull ccoverageoverage JustJJuust -

List of Dubbed Films by DIMAS

www.dimas.sk List of dubbed films by verzia07|2012 DIMAS - Digital Master Studio ORIGINÁLNY NÁZOV SLOVENSKÝ, /CZ/ DISTRIBUČNÝ NÁZOV 300_ 300_ 2012_ 2012_ 1 ½ KNIGHTS–INSEARCHOFTHERAVISHINGPRINCESSHERZELINDE JEDEN A POL RYTIERA 10 000 BC 10 000 PRED KRISTOM 11_59_00 23_59_00 13 GHOSTS 13 DUCHOV 13 GOING ON 30 CEZ NOC TRIDSIATNIČKOU 15 MINUTES 15 MINÚT 16 BLOCKS 16 BLOKOV 17 AGAIN ZNOVA 17 20,000 LEAGUES UNDER TOMEČEKHE SEA 20 000 MÍĽ POD MOROM 3 LITTLE PIGS 3 MALÉ PRASIATKA 30 000 MILE UNDER THE SEA 30 000 MÍĽ POD MOROM 40 DAYS AND 4O NIGHTS 40 DNÍ A 40 NOCÍ 7 MUMMIES 7 MÚMIÍ 8 SECONDS 8 SEKÚND 8 SIMPLE RULES FORDATINGMYTEENAGDAUGHTER 8 JEDNODUCHÝCH PRAVIDIEL, AKO … 01-28 92 IN THE SHADE 33 VE STÍNU A CHRISTMAS CAROL VIANOČNÁ NÁVŠTEVA A DANGEROUS PLACE NEBEZPEČNÉ MÍSTO A FOOL AND HIS MONEY POSADNUTÝ PENIAZMI /POSEDLÍ PENĚZI A MEMORY IN THE HEART SPOMIENKY V SRDCI A POINT MENT FOR A KILLING DOKTOR SMRŤ A PRICE ABOVE RUBIES DRAHŠIA NEŽ RUBÍNY A ROUND THE WORLD CESTA OKOLO SVETA ZA 80 DNÍ A SIMPLE WISH JEDNODUCHÉ ŽELANIE A WALKING THE CLOUDS PRECHÁDZKA V OBLAKOCH ABRAHAM I ABRAHÁM I ABRAHAM II ABRAHÁM II ABSOLUTE ZERO ABSOLÚTNA NULA ABSOLUTHE TRUTH ABSOLÚTNA PRAVDA ACCEPTED NEPRIJATÝ? FPOHO! ACCUSED AT 17 MOJA DCÉRA NIE JE VRAH ACE VENTURA_ PET DETECTIVE ZVIERACÍ DETEKTÍV ADDAMS FAMILY RODINA ADDAMSOVCOV ADDAMS FAMILY VALUES RODINA ADDAMSOVCOV II ADRIFT ODSÚDENÍ ZOMRIEŤ-OTVORENÉ MORE 2 ADRIFT ÚPLNÉ BEZVETRIE 2 /DVA/ ADVENTURE OF SCAMPER DOBRODRUŽSTVO TUČNIAKA MILKA ADVENTURE OF SHARKBOY AND LAVAGIRL IN 3-D DOBRODRUŽSTVÁ NA PLANÉTE DETÍ ADVENTURES OF BLACK FEATHER DOBRODRUŽSTVÁ ČIERNEHO HAVRANA ADVENTURES OF BLACK FEATHER DOBRODRUŽSTVÁ/DOBRODRUŽSTVÍ ČERNÉHO.. -

MTO 22.4: Gotham, Pitch Properties of the Pedal Harp

Volume 22, Number 4, December 2016 Copyright © 2016 Society for Music Theory Pitch Properties of the Pedal Harp, with an Interactive Guide * Mark R. H. Gotham and Iain A. D. Gunn KEYWORDS: harp, pitch, pitch-class set theory, composition, analysis ABSTRACT: This article is aimed at two groups of readers. First, we present an interactive guide to pitch on the pedal harp for anyone wishing to teach or learn about harp pedaling and its associated pitch possibilities. We originally created this in response to a pedagogical need for such a resource in the teaching of composition and orchestration. Secondly, for composers and theorists seeking a more comprehensive understanding of what can be done on this unique instrument, we present a range of empirical-theoretical observations about the properties and prevalence of pitch structures on the pedal harp and the routes among them. This is particularly relevant to those interested in extended-tonal and atonal repertoires. A concluding section discusses prospective theoretical developments and analytical applications. 1 of 21 Received June 2016 I. Introduction [1.1] Most instruments have a relatively clear pitch universe: some have easy access to continuous pitch (unfretted string instruments, voices, the trombone), others are constrained by the 12-tone chromatic scale (most keyboards), and still others are limited to notes of the diatonic or pentatonic scales (many non-Western-orchestral members of the xylophone family). The pedal harp, by contrast, falls somewhere between those last two categories: it is organized around a diatonic configuration, but can reach all 12 notes of the chromatic scale, and most (but not all) pitch-class sets. -

Preliminary Thoughts on Burmese Modes

UC Irvine UC Irvine Previously Published Works Title Preliminary Thoughts on Burmese Modes Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1pd9g1bf Journal Asian Music, VIII(I) Author Garfias, R Publication Date 1975 License CC BY 4.0 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Preliminary Thoughts on Burmese Modes Author(s): Robert Garfias Source: Asian Music, Vol. 7, No. 1, Southeast Asia Issue (1975), pp. 39-49 Published by: University of Texas Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/833926 Accessed: 16-05-2017 22:09 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms University of Texas Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Asian Music This content downloaded from 128.200.102.71 on Tue, 16 May 2017 22:09:55 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms PRELIMINARY THOUGHTS ON BURMESE MODES by Robert Garfias Little precise written information exists concerning the theory of Burmese music. Upon closely investigating the present performance practice of Burmese musicians, however, it becomes apparent that a rather complex orally transmitted theory of the music exists. It is never taught as theory per se, but the knowledge is acquired as the musician adds one composition after another to his repertoire. -

Surrounded by Sound. Experienced Orchestral Harpists' Professional

Surrounded by Sound. Experienced Orchestral Harpists’ Professional Knowledge and Learning Lonnert, Lia 2015 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Lonnert, L. (2015). Surrounded by Sound. Experienced Orchestral Harpists’ Professional Knowledge and Learning. Lund University, Faculty of Fine and Performing Arts, Malmö Academy of Music, Department of Research in Music Education. Total number of authors: 1 General rights Unless other specific re-use rights are stated the following general rights apply: Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal Read more about Creative commons licenses: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. LUND UNIVERSITY PO Box 117 221 00 Lund +46 46-222 00 00 Surrounded by Sound Experienced Orchestral Harpists’ Professional Knowledge and Learning Lia Lonnert 3 © Lia Lonnert Malmö Faculty of Fine and Performing Arts Malmö Academy of Music ISBN 978-91-982297-1-4 ISSN 1404-6539 Printed in Sweden by Media-Tryck, Lund University Lund 2015 En del av Förpacknings- och Tidningsinsamlingen (FTI) 4 Contents Prelude ............................................................................................................... -

The Harp and the Orchestra: an Introductory Guide

THE HARP AND THE ORCHESTRA: AN INTRODUCTORY GUIDE BY ADRIANA HORNE Submitted to the faculty of the Jacobs School of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree, Doctor of Music in Harp Performance Indiana University December, 2013 Accepted by the faculty of the Indiana University Jacobs School of Music, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Music Doctoral Committee ______________________________________ Susann McDonald, Research Director ______________________________________ Elzbieta Szmyt, Chair ______________________________________ Brent Gault ______________________________________ Kathryn Lukas 28 January 2014 ii Copyright © 2013 Adriana Horne iii Acknowledgements Thank you to Elzbieta Szmyt, Kathryn Lukas, and Brent Gault for their help in making this document possible. Special thanks to Susann McDonald for providing such a wealth of encouragement, inspiration, and guidance through the years. iv Table of Contents Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................ iv Table of Contents ................................................................................................................ v List of Examples .............................................................................................................. viii List of Appendices .......................................................................................................... viiii Chapter 1 : The Harp and the Orchestra ............................................................................