Opportunities for Hydrologic Research in the Congo Basin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EAZA Best Practice Guidelines Bonobo (Pan Paniscus)

EAZA Best Practice Guidelines Bonobo (Pan paniscus) Editors: Dr Jeroen Stevens Contact information: Royal Zoological Society of Antwerp – K. Astridplein 26 – B 2018 Antwerp, Belgium Email: [email protected] Name of TAG: Great Ape TAG TAG Chair: Dr. María Teresa Abelló Poveda – Barcelona Zoo [email protected] Edition: First edition - 2020 1 2 EAZA Best Practice Guidelines disclaimer Copyright (February 2020) by EAZA Executive Office, Amsterdam. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in hard copy, machine-readable or other forms without advance written permission from the European Association of Zoos and Aquaria (EAZA). Members of the European Association of Zoos and Aquaria (EAZA) may copy this information for their own use as needed. The information contained in these EAZA Best Practice Guidelines has been obtained from numerous sources believed to be reliable. EAZA and the EAZA APE TAG make a diligent effort to provide a complete and accurate representation of the data in its reports, publications, and services. However, EAZA does not guarantee the accuracy, adequacy, or completeness of any information. EAZA disclaims all liability for errors or omissions that may exist and shall not be liable for any incidental, consequential, or other damages (whether resulting from negligence or otherwise) including, without limitation, exemplary damages or lost profits arising out of or in connection with the use of this publication. Because the technical information provided in the EAZA Best Practice Guidelines can easily be misread or misinterpreted unless properly analysed, EAZA strongly recommends that users of this information consult with the editors in all matters related to data analysis and interpretation. -

Acte Argeo Final

GEOTHERMAL RESOURCE INDICATIONS OF THE GEOLOGIC DEVELOPMENT AND HYDROTHERMAL ACTIVITIES OF D.R.C. Getahun Demissie Addis Abeba, Ethiopia, [email protected] ABSTRACT Published sources report the occurrence of more than 135 thermal springs in D.R.C. All occur in the eastern part of the country, in association with the Western rift and the associated rifted and faulted terrains lying to its west. Limited information was available on the characteristics of the thermal features and the natural conditions under which they occur. Literature study of the regional distribution of these features and of the few relatively better known thermal spring areas, coupled with the evaluation of the gross geologic conditions yielded encouraging results. The occurrence of the anomalously large number of thermal springs is attributed to the prevalence of abnormally high temperature conditions in the upper crust induced by a particularly high standing region of anomalously hot asthenosphere. Among the 29 thermal springs the locations of which could be determined, eight higher temperature features which occur in six geologic environments were found to warrant further investigation. The thermal springs occur in all geologic terrains. Thermal fluid ascent from depth is generally influenced by faulting while its emergence at the surface is controlled by the near-surface hydrology. These factors allow the adoption of simple hydrothermal fluid circulation models which can guide exploration. Field observations and thermal water sampling for chemical analyses are recommended for acquiring the data which will allow the selection of the most promising prospects for detailed, integrated multidisciplinary exploration. An order of priorities is suggested based on economic and technical criteria. -

Evidence from the Kuba Kingdom*

The Evolution of Culture and Institutions:Evidence from the Kuba Kingdom* Sara Lowes† Nathan Nunn‡ James A. Robinson§ Jonathan Weigel¶ 16 November 2015 Abstract: We use variation in historical state centralization to examine the impact of institutions on cultural norms. The Kuba Kingdom, established in Central Africa in the early 17th century by King Shyaam, had more developed state institutions than the other independent villages and chieftaincies in the region. It had an unwritten constitution, separation of political powers, a judicial system with courts and juries, a police force and military, taxation, and significant public goods provision. Comparing individuals from the Kuba Kingdom to those from just outside the Kingdom, we find that centralized formal institutions are associated with weaker norms of rule-following and a greater propensity to cheat for material gain. Keywords: Culture, values, institutions, state centralization. JEL Classification: D03,N47. *A number of individuals provided valuable help during the project. We thank Anne Degrave, James Diderich, Muana Kasongo, Eduardo Montero, Roger Makombo, Jim Mukenge, Eva Ng, Matthew Summers, Adam Xu, and Jonathan Yantzi. For comments, we thank Ran Abramitzky, Chris Blattman, Jean Ensminger, James Fenske, Raquel Fernandez, Carolina Ferrerosa-Young, Avner Greif, Joseph Henrich, Karla Hoff, Christine Kenneally, Alexey Makarin, Anselm Rink, Noam Yuchtman, as well as participants at numerous conferences and seminars. We gratefully acknowledge funding from the Pershing Square Venture Fund for Research on the Foundations of Human Behavior and the National Science Foundation (NSF). †Harvard University. (email: [email protected]) ‡Harvard University, NBER and BREAD. (email: [email protected]) §University of Chicago, NBER, and BREAD. -

Hybridization Between the Megasubspecies Cailliautii and Permista of the Green-Backed Woodpecker, Campethera Cailliautii

Le Gerfaut 77: 187–204 (1987) HYBRIDIZATION BETWEEN THE MEGASUBSPECIES CAILLIAUTII AND PERMISTA OF THE GREEN-BACKED WOODPECKER, CAMPETHERA CAILLIAUTII Alexandre Prigogine The two woodpeckers, Campethera cailliautii (with races nyansae, “fuel leborni”, loveridgei) and C. permista (with races togoensis, kaffensis) were long regarded as distinct species (Sclater, 1924; Chapin 1939). They are quite dissimi lar: permista has a plain green mantle and barred underparts, while cailliautii is characterized by clear spots on the upper side and black spots on the underpart. The possibility that they would be conspecific was however considered by van Someren in 1944. Later, van Someren and van Someren (1949) found that speci mens of C. permista collected in the Bwamba Forest tended strongly toward C. cailliautii nyansae and suggested again that permista and cailliautii may be con specific. Chapin (1952) formally treated permista as a subspecies of C. cailliautii, noting two intermediates from the region of Kasongo and Katombe, Zaire, and referring to a correspondence of Schouteden who confirmed the presence of other intermediates from Kasai in the collection of the MRAC (see Annex 2). Hall (1960) reported two intermediates from the Luau River and from near Vila Luso, Angola. Traylor (1963) noted intermediates from eastern Lunda. Pinto (1983) mentioned seven intermediates from Dundo, Mwaoka, Lake Carumbo and Cafunfo (Luango). Thus the contact zone between permista and nyansae extends from the region north-west of Lake Tanganyika to Angola, crossing Kasai, in Zaire. A second, shorter, contact zone may exist near the eastern border of Zaire, not far from the Equator. The map published by Short and Tarbaton (in Snow 1978) shows cailliautii from the Semliki Valley, on the Equator but I know of no speci mens of this woodpecker from this region. -

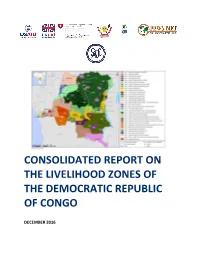

DRC Consolidated Zoning Report

CONSOLIDATED REPORT ON THE LIVELIHOOD ZONES OF THE DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF CONGO DECEMBER 2016 Contents ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS ......................................................................................... 5 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .......................................................................................................... 6 1. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................ 7 1.1 Livelihoods zoning ....................................................................................................................7 1.2 Implementation of the livelihood zoning ...................................................................................8 2. RURAL LIVELIHOODS IN DRC - AN OVERVIEW .................................................................. 11 2.1 The geographical context ........................................................................................................ 11 2.2 The shared context of the livelihood zones ............................................................................. 14 2.3 Food security questions ......................................................................................................... 16 3. SUMMARY DESCRIPTIONS OF THE LIVELIHOOD ZONES .................................................... 18 CD01 COPPERBELT AND MARGINAL AGRICULTURE ....................................................................... 18 CD01: Seasonal calendar .................................................................................................................... -

Tracing the Linguistic Origins of Slaves Leaving Angola, 1811-1848

From beyond the Kwango - Tracing the Linguistic Origins of Slaves Leaving Angola, 1811-1848 DOI http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/2236-463320161203 Badi Bukas-Yakabuul Resumo Atlanta First Presbyterian Church, O Rio Quango tem sido visto há muito tempo como o limite do acesso Atlanta - EUA dos traficantes de escravos às principais fontes de cativos no interior [email protected] de Angola, a maior região de embarque de escravos para as Américas. Contudo, não há estimativas sobre o tamanho e a distribuição dessa Daniel B. Domingues da Silva enorme migração. Este artigo examina registros de africanos libertados de Cuba e Serra Leoa disponíveis no Portal Origens Africanas para estimar University of Missouri, Columbia - o número de escravos provenientes daquela região em particular durante EUA o século XIX além da sua distribuição etnolingüística. Ele demonstra [email protected] que cerca de 21 porcento dos escravos transportados de Angola naquele período vieram de além Quango, sendo a maioria oriunda dos povos luba, canioque, e suaíli. O artigo também analisa as causas dessa migração, que ajudou a transformar a diáspora africana para as Américas, especialmente para o Brasil e Cuba. Abstract The Kwango River has long been viewed as the limit of the transatlantic traders’ access to the main sources of slaves in the interior of Angola, the principal region of slave embarkation to the Americas. However, no estimates of the size and distribution of this huge migration exist. This article examines records of liberated Africans from Cuba and Sierra Leone available on the African Origins Portal to estimate how many slaves came from that particular region in the nineteenth century as well as their ethnolinguistic distribution. -

Climatic Effects on Lake Basins. Part I: Modeling Tropical Lake Levels

15 JUNE 2011 R I C K O E T A L . 2983 Climatic Effects on Lake Basins. Part I: Modeling Tropical Lake Levels MARTINA RICKO AND JAMES A. CARTON Department of Atmospheric and Oceanic Science, University of Maryland, College Park, College Park, Maryland CHARON BIRKETT Earth System Science Interdisciplinary Center, University of Maryland, College Park, College Park, Maryland (Manuscript received 28 December 2009, in final form 9 December 2010) ABSTRACT The availability of satellite estimates of rainfall and lake levels offers exciting new opportunities to estimate the hydrologic properties of lake systems. Combined with simple basin models, connections to climatic variations can then be explored with a focus on a future ability to predict changes in storage volume for water resources or natural hazards concerns. This study examines the capability of a simple basin model to estimate variations in water level for 12 tropical lakes and reservoirs during a 16-yr remotely sensed observation period (1992–2007). The model is constructed with two empirical parameters: effective catchment to lake area ratio and time delay between freshwater flux and lake level response. Rainfall datasets, one reanalysis and two satellite-based observational products, and two radar-altimetry-derived lake level datasets are explored and cross checked. Good agreement is observed between the two lake level datasets with the lowest correlations occurring for the two small lakes Kainji and Tana (0.87 and 0.89). Fitting observations to the simple basin model provides a set of delay times between rainfall and level rise ranging up to 105 days and effective catchment to lake ratios ranging between 2 and 27. -

Results of Railway Privatization in Africa

36005 THE WORLD BANK GROUP WASHINGTON, D.C. TP-8 TRANSPORT PAPERS SEPTEMBER 2005 Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Results of Railway Privatization in Africa Richard Bullock. Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized TRANSPORT SECTOR BOARD RESULTS OF RAILWAY PRIVATIZATION IN AFRICA Richard Bullock TRANSPORT THE WORLD BANK SECTOR Washington, D.C. BOARD © 2005 The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank 1818 H Street NW Washington, DC 20433 Telephone 202-473-1000 Internet www/worldbank.org Published September 2005 The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed here are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Board of Executive Directors of the World Bank or the governments they represent. This paper has been produced with the financial assistance of a grant from TRISP, a partnership between the UK Department for International Development and the World Bank, for learning and sharing of knowledge in the fields of transport and rural infrastructure services. To order additional copies of this publication, please send an e-mail to the Transport Help Desk [email protected] Transport publications are available on-line at http://www.worldbank.org/transport/ RESULTS OF RAILWAY PRIVATIZATION IN AFRICA iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface .................................................................................................................................v Author’s Note ...................................................................................................................... -

Lake Tanganyika Geochemical and Hydrographic Study: 1973 Expedition

UC San Diego SIO Reference Title Lake Tanganyika Geochemical and Hydrographic Study: 1973 Expedition Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4ct114wz Author Craig, Harmon Publication Date 1974-12-01 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Scripps Institution of Oceanography University of California, San Diego La Jolla, California 92037 LAKE TANGANYIKA GEOCHEMICAL AND HYDROGRAPHIC STUDY: 1973 EXPEDITION Compiled by: H. Craig December 19 74 SIO Reference Series 75-5 TABLE OF- CONTENTS SECTTON I. [NTI<OI)UC'I' LON SECTION 11. STATION POSITIONS, SAEZI'LING I.OCATIONS, STATION 1 CAST LISTS, BT DATA SFCTION 111. HYDROGRAPHIC DATA, MEASUREMENTS AT SIO 111-1. Hydrographic Data: T, c1 111-2. Total C02 and C13/~12Ratios 111-3. Radiunl-226 111-4. Lead-210 111-5. Hel.ium and He 3 /He4 Ratios 111-6. Deuterium and Oxygen-18 111-7. References, Section 111 SECTION IV. LAW CKEMISTRY: EZEASIIREMENTS AT MLT IV-1. Major Ions IV-2. Nutrients IV-3. Barium SECTION V. UNIVERSITY OF MIAMI CONTRIBUTIONS V-1. Tritium Measurements V-2. Equation oE State STA'SLON I'OSITIONS, LAKE SURFACE IJKSl$I< SAMPLES RIVER SAMPLE LOCATIONS STATION 1: Complete Cast List STATION 1: Bottle Depths by Cast STATION 1: Depths Sampled and Corresponding Dot tle Numbers 16 Bc\TltYTI1ERMOGRAP1I MEASUREMENTS 18 MY1)ROGMPI-IIC DATA: STATION 1 STATIONS 2, 3 STATIONS 4, 5 CMLORZDIS DATA: STATIONS A, B, C; RIVERS TOTAL C02 AND 6C13: STATION 1 STATIONS 2 - 5 RADIUM-226 PROFILES: STATIOV 1 LEAD-210 PROFI1,E : STATION 1 I-IELIUM 3 AND 4 PROFILES DEUTERIUM, OXYGEN-18: STATION 1 STATIONS 2, 3 STATIONS 4, 5 STATIONS A, B, C; RIVER SAMPLES D, 018, CHLORIDE; TIME SERIES: STATION 5 RUZIZI RIVER MAJOR ION DATA: STATION 1 67 RIVER SAMPLES 68 NUTRIENT DATA: STATION 1 7 1 STATIONS 2 - 5 7 2 RIVER SMLES 7 3 SILICATE: RUZIZI RIVER, STATION 5, TIME SERIES 74 BARIUM: STATION 1 75 TRITIUM DATA: LAKE SURFACE AND STATION 1 RIVER ShElPLES sii T,oci~Cion oE Stations, 1,nlte surface s;~n~ples, ant1 Kiver samples. -

Case 1:19-Cv-03737 Document 1 Filed 12/15/19 Page 1 of 79

Case 1:19-cv-03737 Document 1 Filed 12/15/19 Page 1 of 79 TERRENCE COLLINGSWORTH (DC Bar # 471830) International Rights Advocates 621 Maryland Ave NE Washington, D.C. 20002 Tel: 202-543-5811 E-mail: [email protected] Counsel for Plaintiffs UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA ________________ JANE DOE 1, Individually and on behalf of Proposed Class Members; JOHN DOE 1, Individually and on behalf of Proposed Class Members; JOHN DOE 2, Individually and on behalf of Proposed Class Members; JENNA ROE 3, Individually and on behalf of Proposed Class Members; JAMES DOE 4, Individually and on Case No. CV: behalf of Proposed Class Members; JOHN DOE 5, Individually and on behalf of Proposed Class Members; JENNA DOE 6, Individually and on CLASS COMPLAINT FOR behalf of Proposed Class Members; INJUNCTIVE RELIEF AND JANE DOE 2, Individually and on DAMAGES behalf of Proposed Class Members; JENNA DOE 7, Individually and on behalf of Proposed Class Members; JURY TRIAL DEMANDED JENNA DOE 8, Individually and on behalf of Proposed Class Members; JOHN DOE 9, Individually and on behalf of Proposed Class Members; JENNA DOE 10, Individually and on behalf of Proposed Class Members; JENNA DOE 11, Individually and on behalf of Proposed Class Members; JANE DOE 3, Individually and on behalf of Proposed Class Members; JOHN DOE 12, Individually and on 1 Case 1:19-cv-03737 Document 1 Filed 12/15/19 Page 2 of 79 behalf of Proposed Class Members; and JOHN DOE 13, Individually and on behalf of Proposed Class Members; all Plaintiffs C/O 621 Maryland Ave. -

New Species of Congoglanis (Siluriformes: Amphiliidae) from the Southern Congo River Basin

New Species of Congoglanis (Siluriformes: Amphiliidae) from the Southern Congo River Basin Richard P. Vari1, Carl J. Ferraris, Jr.2, and Paul H. Skelton3 Copeia 2012, No. 4, 626–630 New Species of Congoglanis (Siluriformes: Amphiliidae) from the Southern Congo River Basin Richard P. Vari1, Carl J. Ferraris, Jr.2, and Paul H. Skelton3 A new species of catfish of the subfamily Doumeinae, of the African family Amphiliidae, was discovered from the Kasai River system in northeastern Angola and given the name Congoglanis howesi. The new species exhibits a combination of proportional body measurements that readily distinguishes it from all congeners. This brings to four the number of species of Congoglanis, all of which are endemic to the Congo River basin. ECENT analyses of catfishes of the subfamily Congoglanis howesi, new species Doumeinae of the African family Amphiliidae Figures 1, 2; Table 1 R documented that the species-level diversity and Doumea alula, Poll, 1967:265, fig. 126 [in part, samples from morphological variation of some components of the Angola, Luachimo River, Luachimo rapids; habitat infor- subfamily were dramatically higher than previously mation; indigenous names]. suspected (Ferraris et al., 2010, 2011). One noteworthy discovery was that what had been thought to be Doumea Holotype.—MRAC 162332, 81 mm SL, Angola, Lunda Norte, alula not only encompassed three species, but also that Kasai River basin, Luachimo River, Luachimo rapids, 7u219S, they all lacked some characters considered diagnostic of 20u509E, in residual pools downstream of dam, A. de Barros the Doumeinae. Ferraris et al. (2011) assigned those Machado, E. Luna de Carvalho, and local fishers, 10 Congoglanis species to a new genus, , which they hypoth- February 1957. -

Tapori Newsletter

TAPORI ADDRESS is a worldwide friendship network 12, RUE PASTEUR which brings together children from 95480 PIERRELAYE Tapori different backgrounds who want alll FRANCE children to have the same chances. They learn from children whose MAIL everyday life is very different from theirs. They think and act for a fairer [email protected] Newsletter world by inventing a way of living where no one is left behind. WEBSITE N°430, November 2020-January 2021 fr.tapori.org Dear Taporis, After a long break due to the Covid-19 pandemic, we discovered that many of you went back to school. Despite the resumption of classes, some cannot go to school every day. Many have not been able to go back at all. We wish you a lot of courage, whatever your situation is. We hope you can keep the desire to learn. In this letter, we want to share with you the messages that we received from children from different countries. They tell us about how each one does their part to take care of others and of the planet, like the hummingbird, bringing water droplets to the great fire. "I look after you. You look after me." ; is the message that stood out from their reflections and their actions. Another theme in their messages was the water that surrounds them in their everyday life. You will discover children living by rivers, lakes and seas who know very well that every single one of their actions, as simple as they might seem, can impact their community. We hope that their messages can inspire you and that you can yourself be committed, wherever you are.