The National School Mapping and Micro-Planning Project in the Republic of Malawi - Micro-Planning Component

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Summary Report 2017

Malawi Country Oice Summary Report 2017 UNFPA in Malawi aims to promote universal access to sexual and reproductive health, realize reproductive rights, and reduce maternal mortality to accelerate progress on the agenda of the Programme of Action of the International Conference on Population and Development, to improve the lives of women, adolescents and youth, enabled by population dynamics, human rights and gender equality. Malawi Country Office Summary Report 2017 UNFPA supports programmes in thematic areas of: Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights including Family Planning, Maternal Health, HIV and AIDS, and Fistula Population and Development Humanitarian Emergencies Gender Equality and GBV including Ending Child Marriages These are delivered by working with the Ministry of Health and Population; Ministry of Finance, Economic Planning and Development; Ministry of Labour, Youth and Manpower Development; Ministry of Gender, Children, Disability and Social Welfare among other government institutions and non-state actors. While the Government Ministries implement some of the strategic activities on policy and guidelines, most of the community and facility based interventions at the service delivery level are implemented by District Councils and local non-governmental organizations. 1 UNFPA Malawi strategically supports seven districts of Chiradzulu, Salima, Mangochi, Mchinji, Dedza, Chikhwawa and Nkhata-bay. Nkhata Bay Northern Region Central Region Southern Region Salima Mchinji Mangochi Dedza Chikhwawa Chiradzulu Impact districts -

Map District Site Balaka Balaka District Hospital Balaka Balaka Opd

Map District Site Balaka Balaka District Hospital Balaka Balaka Opd Health Centre Balaka Chiendausiku Health Centre Balaka Kalembo Health Centre Balaka Kankao Health Centre Balaka Kwitanda Health Centre Balaka Mbera Health Centre Balaka Namanolo Health Centre Balaka Namdumbo Health Centre Balaka Phalula Health Centre Balaka Phimbi Health Centre Balaka Utale 1 Health Centre Balaka Utale 2 Health Centre Blantyre Bangwe Health Centre Blantyre Blantyre Adventist Hospital Blantyre Blantyre City Assembly Clinic Blantyre Chavala Health Centre Blantyre Chichiri Prison Clinic Blantyre Chikowa Health Centre Blantyre Chileka Health Centre Blantyre Blantyre Chilomoni Health Centre Blantyre Chimembe Health Centre Blantyre Chirimba Health Centre Blantyre Dziwe Health Centre Blantyre Kadidi Health Centre Blantyre Limbe Health Centre Blantyre Lirangwe Health Centre Blantyre Lundu Health Centre Blantyre Macro Blantyre Blantyre Madziabango Health Centre Blantyre Makata Health Centre Lunzu Blantyre Makhetha Clinic Blantyre Masm Medi Clinic Limbe Blantyre Mdeka Health Centre Blantyre Mlambe Mission Hospital Blantyre Mpemba Health Centre Blantyre Ndirande Health Centre Blantyre Queen Elizabeth Central Hospital Blantyre South Lunzu Health Centre Blantyre Zingwangwa Health Centre Chikwawa Chapananga Health Centre Chikwawa Chikwawa District Hospital Chikwawa Chipwaila Health Centre Chikwawa Dolo Health Centre Chikwawa Kakoma Health Centre Map District Site Chikwawa Kalulu Health Centre, Chikwawa Chikwawa Makhwira Health Centre Chikwawa Mapelera Health Centre -

Master Plan Study on Rural Electrification in Malawi Final Report

No. JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY (JICA) MINISTRY OF NATURAL RESOURCES AND ENVIRONMENTAL AFFAIRS (MONREA) DEPARTMENT OF ENERGY AFFAIRS (DOE) REPUBLIC OF MALAWI MASTER PLAN STUDY ON RURAL ELECTRIFICATION IN MALAWI FINAL REPORT MAIN REPORT MARCH 2003 TOKYO ELECTRIC POWER SERVICES CO., LTD. MPN NOMURA RESEARCH INSTITUTE, LTD. JR 03-023 Contents 0 Executive Summary .................................................................................................................... 1 1 Background and Objectives ........................................................................................................ 4 1.1 Background ......................................................................................................................... 4 1.2 Objectives............................................................................................................................ 8 2 Process of Master Plan................................................................................................................ 9 2.1 Basic guidelines .................................................................................................................. 9 2.2 Identification of electrification sites ................................................................................. 10 2.3 Data and information collection........................................................................................ 10 2.4 Prioritization of electrification sites................................................................................. -

Southern Africa - Drought Fact Sheet #1, Fiscal Year (Fy) 2016 April 8, 2016

SOUTHERN AFRICA - DROUGHT FACT SHEET #1, FISCAL YEAR (FY) 2016 APRIL 8, 2016 NUMBERS AT HIGHLIGHTS HUMANITARIAN FUNDING A GLANCE FOR THE SOUTHERN AFRICA DROUGHT Eight countries in the region record lowest RESPONSE IN FY 2016 rainfall amounts in 35 years USAID/OFDA1 $216,611 12.8 Food insecurity affects 12.8 million people million USAID/FFP2 $47,158,300 Food-Insecure People in in Southern Africa; may affect nearly 36 Southern Africa* million people by late 2016 UN – March 2016 $47,374,911 USAID/FFP provides nearly $47.2 million in emergency food assistance in Malawi and 2.9 million Zimbabwe Food-Insecure People in Malawi UN – March 2016 KEY DEVELOPMENTS During the 2015/2016 October-to-January rainy season, many areas of Southern Africa experienced the lowest-recorded rainfall amounts in 35 years, resulting in widespread 2.8 drought conditions, according to the USAID-funded Famine Early Warning Systems million Network (FEWS NET). The drought, exacerbated by the 2015/2016 El Niño climatic Food-Insecure People in event, is causing deteriorating food security, agriculture, livestock, nutrition, and water Zimbabwe conditions throughout the region, with significant humanitarian needs anticipated UN – March 2016 through at least April 2017, the UN reports. Response actors report that the Southern African Development Community (SADC)— 1.5 an inter-governmental organization to promote cooperation among 15 Southern African countries on regional issues—is preparing a regional disaster declaration, response plan, million and funding appeal in coordination with the UN to support drought-affected countries in Food-Insecure People in Mozambique the region. The appeal presents an opportunity for host country governments to GRM – April 2016 prioritize requests for assistance responding to the effects of widespread drought conditions and consequent negative impacts on planting and harvesting. -

REPUBLIC of MALAWI Poverty Assessment

REPUBLIC OF MALAWI Poverty Assessment Poverty and Equity Global Practice Africa Region REPUBLIC OF MALAWI Poverty Assessment Poverty and Equity Global Practice Africa Region June, 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements ...................................................................................................................................... xv Abbreviations .............................................................................................................................................xvii CHAPTER 1: Poverty and Shared Prosperity in Malawi, 2004–2010 ..........................................................1 1.1. Snapshot of Poverty in Malawi ..................................................................................................................1 1.2. Where Are the Poor and Who Are They? ..................................................................................................5 1.2.1. Incidence of poverty and inequality across space ..........................................................................................5 1.2.2. Who are the poor? ...................................................................................................................................8 1.3. Shared Prosperity ..................................................................................................................................... 10 1.3.1. Incidence of growth of consumption and monetary poverty ......................................................................... 10 1.3.2. High and persistent -

In Malawi: Selected Findings on Livelihood

The Program on Governance and Local Development The Local Governance Performance Index (LGPI) in Malawi: Selected Findings on Livelihood Report October 2016 SERIES 2016:5 Acknowledgements This project reflects fruitful collaboration of researchers at the Christian Michelson Institute, including Ragnhild Muriaas, Lise Rakner and Vibeke Wang; the Institute for Public Opinion and Research, including Asiyati Chiweza, Boniface Dulani, Happy Kayuni, Hannah Swila and Atusaye Zgambo; and the Program on Governance and Local Development, including Adam Harris, Kristen Kao, Ellen Lust, Maria Thorson, Jens Ewald, Petter Holmgren, Pierre Landry and Lindsay Benstead during implementation, and in addition Ruth Carlitz, Sebastian Nickel, Benjamin Akinyemi, Laura Lungu and Tove Wikehult in the process of data cleaning and analysis. We gratefully recognize the hard work of colleagues at the Institute for Public Opinion and Research who lead the survey research teams. These include, Ellasy Chimimba, Grace Gundula, Steve Liwera, Shonduri Manda, Alfred Mangani, Razak Mussa, Bernard Nyirenda, Charles Sisya and Elizabeth Tizola. We also thank Jane Steinberg, who provided excellent and timely editing of this report. Finally, we reserve special recognition for Ruth Carlitz, who led this report. This project has been made possible with the financial support of the Moulay Hicham Foundation, the Carnegie Corporation of New York, The World Bank and Yale University, which funded development of the Local Governance Performance Index, and the Swedish Research Council and the Research Council of Norway, which funded implementation in Norway. We are grateful for their support. 1 Executive Summary Malawi is one of the poorest countries in the world, with a gross national income per capita of just 747 U.S. -

Malawi Coverage Survey 2017

Malawi Coverage Survey 2017 Measuring treatment coverage for schistosomiasis and soil transmitted helminths with preventive chemotherapy 1 Contents Contents .................................................................................................................................................. 2 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 4 Background to the Coverage Survey ....................................................................................................... 4 Schistosomiasis and STH in Malawi .................................................................................................... 5 Previous mapping ............................................................................................................................... 5 Treatment History ............................................................................................................................... 5 Previous Coverage Surveys ................................................................................................................. 6 2012 ................................................................................................................................................ 6 2014 ................................................................................................................................................ 6 2016 ............................................................................................................................................... -

Connectivity Solutions for 752 PEPFAR Supported MOH Clinics

REQUEST FOR PROPOSALS (RFP) #MAL-122019-EMR Connectivity Solutions for 752 PEPFAR Supported MOH Clinics ELIZABETH GLASER PEDIATRIC AIDS FOUNDATION (EGPAF) NED BANK House, City Centre, P.O. Box 2543, Lilongwe, Malawi FIRM DEADLINE: Friday, 17 January 2020 at 11am INTRODUCTION Elizabeth Glaser Pediatric AIDS Foundation (“EGPAF” or “Foundation”), a non-profit organization, is a world leader in the fight to eliminate pediatric AIDS. Our mission is to prevent pediatric HIV infection and to eliminate pediatric AIDS through research, advocacy, and prevention and treatment programs. For more information, please visit http://www.pedaids.org. OBJECTIVE OF THE ASSIGNMENT | SCOPE OF WORK | EXPECTED DELIVERABLES EGPAF seeks to contract with a reputable Vendor to immediately meet our current connectivity needs (with the possibility of fulfilling future needs as they arise) in support of an ambitious national Electronic Medical Records (EMR) initiative. It is anticipated that the selected Vendor can assess our requirements, develop a comprehensive and effective solution to implement at all 752 PEPFAR-supported MOH Clinics throughout Malawi (see Attachment 1), and eventually implement and install, in coordination with the necessary Foundation staff, all necessary infrastructure at each site to reflect its proposed solution(s). More specifically, the selected Contractor is expected to offer a fast and affordable Carrier Backbone network services to cover 752 clinics across the 28 Districts in Malawi to support regular and incremental data transmission from the Clinics/health facilities to a Central Data Repository hosted at the Ministry of Health. The winning Contractor will be responsible for installation of last mile connection to connect each health facility to the backbone network, including configuring Point-to-Point connections between the health facility and the Central Data Repository. -

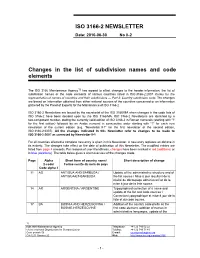

ISO 3166-2 NEWSLETTER Changes in the List of Subdivision Names And

ISO 3166-2 NEWSLETTER Date: 2010-06-30 No II-2 Changes in the list of subdivision names and code elements The ISO 3166 Maintenance Agency1) has agreed to effect changes to the header information, the list of subdivision names or the code elements of various countries listed in ISO 3166-2:2007 Codes for the representation of names of countries and their subdivisions — Part 2: Country subdivision code. The changes are based on information obtained from either national sources of the countries concerned or on information gathered by the Panel of Experts for the Maintenance of ISO 3166-2. ISO 3166-2 Newsletters are issued by the secretariat of the ISO 3166/MA when changes in the code lists of ISO 3166-2 have been decided upon by the ISO 3166/MA. ISO 3166-2 Newsletters are identified by a two-component number, stating the currently valid edition of ISO 3166-2 in Roman numerals (starting with "I" for the first edition) followed by an Arabic numeral in consecutive order starting with "1" for each new newsletter of the current edition (e.g. "Newsletter II-1" for the first newsletter of the second edition, ISO 3166-2:2007). All the changes indicated in this Newsletter refer to changes to be made to ISO 3166-2:2007 as corrected by Newsletter II-1. For all countries affected a complete new entry is given in this Newsletter. A new entry replaces an old one in its entirety. The changes take effect on the date of publication of this Newsletter. The modified entries are listed from page 4 onwards. -

Crop Residues As a Potential Renewable Energy Source for Malawi’S Cement Industry

Volume 28 Number 4 Crop residues as a potential renewable energy source for Malawi’s cement industry Kenneth J. Gondwe 1* , Sosten S. Chiotha 2, Theresa Mkandawire 1, Xianli Zhu 3, Jyoti Painuly 3, John L.Taulo 4 1 University of Malawi-The Polytechnic, Blantyre, Malawi 2 Leadership for Environment and Development, Zomba, Malawi 3 UNEP-DTU Partnership, Technical University of Denmark, Copenhagen, Denmark 4 Industrial Research Centre, Malawi University of Science and Technology, Limbe, Malawi Abstract sumption would be avoided and 46 128 t of carbon Crop residues have been undervalued as a source dioxide emission reduction achieved per year. For of renewable energy to displace coal in the national sustainability, holistic planning and implementation energy mix for greenhouse emission reduction in would be necessary to ensure the needs of various Malawi. Switching to crop residues as an alternative users of crop residues are met. Furthermore, there energy source for energy-intensive industries such would be a need to address social, economic and as cement manufacturing is hampered by uncertain - environmental barriers of the crop residue-based ties in crop residue availability, cost and quality. In biomass energy supply chain. Future research this study, future demand for energy and availability should focus on local residue-to-product ratios and of crop residues was assessed, based on data at the their calorific values. sub-national level. Detailed energy potentials from crop residues were computed for eight agricultural Keywords: biomass energy, clinker, energy-inten - divisions. The results showed that the projected total sive industry, coal, CO 2 emissions energy demands in 2020, 2025 and 2030 were approximately 177 810 TJ, 184 210 TJ and Highlights 194 096 TJ respectively. -

Agriculture and the Socio- Economic Environment

E4362 v1 REPUBLIC OF MALAWI Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Ministry of Agriculture and Food Security Agricultural Sector Wide Approach – Support Project – Additional Financing Public Disclosure Authorized ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL MANAGEMENT FRAMEWORK (ESMF) DRAFT FINAL REPORT Ministry of Agriculture and Food Security Capital Hill P O Box 30134 Public Disclosure Authorized Capital City Lilongwe 3 MALAWI January 2012 Updated November 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ........................................................................................................... ii LIST OF ACRONYMS ............................................................................................................. v EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ..................................................................................................... vii CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND ............................................ 13 1.1 The National Context .............................................................................................. 13 1.2 The Agriculture Sector ........................................................................................... 13 1.3 The Agricultural Sector Wide Approach Support Project (ASWAp-SP) ......... 14 1.3.1 Project Development Objectives ............................................................................. 15 1.3.2 Programme Components and additional activities................................................. 16 1.3.3 Description of sub-components.............................................................................. -

MALAWI Main Health Facilities and Population Density March 2020

MALAWI Main Health Facilities and Population Density March 2020 Chitipa Chitipa District CHITIPA Hospital Karonga District Karonga old Hospital Hospital KARONGA Chilumba UNITED REPUBLIC OF TANZANIA RUMPHI Rumphi Rumphi District Hospital ZAMBIA NORTHERN MZUZU CITY Mzuzu Central MZUZU Hospital Nkhata Bay NKHATA BAY Nkhata Bay MZIMBA District Hospital Mzimba District Hospital LIKOMA LILONGWE CITY Lake Malawi MOZAMBIQUE Lilongwe Central Hospital Bwaila/Bottom Hospital NKHOTAKOTA KASUNGU Nkhotakota District Hospital Kasungu Kasungu District Hospital NTCHISI ZOMBA CITY Ntchisi District CENTRAL Hospital DOWA Dzaleka Refugee Camp (44,385) MCHINJI Dowa SALIMA Dowa District Salima District Mchinji District Hospital Hospital ZOMBA Hospital LILONGWE CITY ZOMBA CITY Zomba Central Hospital DEDZA LILONGWE Dedza Dedza District BLANTYRE CITY Hospital Mangoche Mangochi District ZOMBA MANGOCHI Hospital NTCHEU Ntcheu Ntcheu District Hospital BLANTYRE CITY Capital City MACHINGA CHIRADZULU Balaka District Liwonde BLANTYRE Queen Elizabeth Central Hospital Hospital Major town MOZAMBIQUE Machinga District Hospital BALAKA Refugee camp / settlement Machinga LIMBE Lake (Number of refugees) ZOMBA CITY Chilwa NENO Road Zomba Central Hospital Mwanza District Hospital SOUTHERN ZOMBA District BLANTYRE PHALOMBE THYOLO BLANTYRE Region MWANZA Chiradzulu District Hospital CHIRADZULU International border BLANTYRE CITY MULANJE Chikwawa District Health facility Hospital Thyolo District Mulanje District Hospital Hospital Central Hospital District Hospital CHIKWAWA THYOLO Population density (People per Sq. Km) < 100 Bangula 101 - 250 NSANJE 251 - 500 ZIMBABWE Nsanje District Hospital 501 - 1,000 > 1,000 The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. Creation date: 3 Apr 2020 Sources: OSM, UNCS, UNOCHA, Camps: UNHCR, Health Facilities: HDX/WHO-CDC, Population Density: Malawi NSO Feedback: [email protected] | Twitter: @UNOCHA_ROSEA | www.unocha.org/rosea | www.reliefweb.int.