In Malawi: Selected Findings on Livelihood

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The National School Mapping and Micro-Planning Project in the Republic of Malawi - Micro-Planning Component

No. Ministry of Education, Japan International Science and Technology Cooperation Agency Republic of Malawi THE NATIONAL SCHOOL MAPPING AND MICRO-PLANNING PROJECT IN THE REPUBLIC OF MALAWI - MICRO-PLANNING COMPONENT- FINAL REPORT AUGUST 2002 KRI INTERNATIONAL CORP. SSF JR 02-118 PREFACE In response to a request from the Government of the Republic of Malawi, the Government of Japan decided to conduct the National School Mapping and Micro-Planning Project and entrusted it to the Japan International Cooperation Agency. JICA selected and dispatched a project team headed by Ms. Yoko Ishida of the KRI International Corp., to Malawi, four times between November 2000 and July 2002. In addition, JICA set up an advisory committee headed by Mr. Nobuhide Sawamura, Associate Professor of Hiroshima University, between October 2000 and June 2002, which examined the project from specialist and technical point of view. The team held discussions with the officials concerned of the Government of Malawi and implemented the project activities in the target areas. Upon returning to Japan, the team conducted further analyses and prepared this final report. I hope that this report will contribute to the promotion of the quality education provision in Malawi and to the enhancement of friendly relations between our two countries. Finally, I wish to express my sincere appreciation to the officials concerned of the Government of Malawi for their close cooperation extended to the project. August 2002 Takeo Kawakami President Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) Lake Malawi 40 ° 20° ° 40 40° 0° Kinshasa ba ANGOLA Victoria bar Lake SEYCHELLES Tanganyika Ascension ATLANTIC (UK) Luanda Aldabra Is. -

Southern Africa - Drought Fact Sheet #1, Fiscal Year (Fy) 2016 April 8, 2016

SOUTHERN AFRICA - DROUGHT FACT SHEET #1, FISCAL YEAR (FY) 2016 APRIL 8, 2016 NUMBERS AT HIGHLIGHTS HUMANITARIAN FUNDING A GLANCE FOR THE SOUTHERN AFRICA DROUGHT Eight countries in the region record lowest RESPONSE IN FY 2016 rainfall amounts in 35 years USAID/OFDA1 $216,611 12.8 Food insecurity affects 12.8 million people million USAID/FFP2 $47,158,300 Food-Insecure People in in Southern Africa; may affect nearly 36 Southern Africa* million people by late 2016 UN – March 2016 $47,374,911 USAID/FFP provides nearly $47.2 million in emergency food assistance in Malawi and 2.9 million Zimbabwe Food-Insecure People in Malawi UN – March 2016 KEY DEVELOPMENTS During the 2015/2016 October-to-January rainy season, many areas of Southern Africa experienced the lowest-recorded rainfall amounts in 35 years, resulting in widespread 2.8 drought conditions, according to the USAID-funded Famine Early Warning Systems million Network (FEWS NET). The drought, exacerbated by the 2015/2016 El Niño climatic Food-Insecure People in event, is causing deteriorating food security, agriculture, livestock, nutrition, and water Zimbabwe conditions throughout the region, with significant humanitarian needs anticipated UN – March 2016 through at least April 2017, the UN reports. Response actors report that the Southern African Development Community (SADC)— 1.5 an inter-governmental organization to promote cooperation among 15 Southern African countries on regional issues—is preparing a regional disaster declaration, response plan, million and funding appeal in coordination with the UN to support drought-affected countries in Food-Insecure People in Mozambique the region. The appeal presents an opportunity for host country governments to GRM – April 2016 prioritize requests for assistance responding to the effects of widespread drought conditions and consequent negative impacts on planting and harvesting. -

REPUBLIC of MALAWI Poverty Assessment

REPUBLIC OF MALAWI Poverty Assessment Poverty and Equity Global Practice Africa Region REPUBLIC OF MALAWI Poverty Assessment Poverty and Equity Global Practice Africa Region June, 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements ...................................................................................................................................... xv Abbreviations .............................................................................................................................................xvii CHAPTER 1: Poverty and Shared Prosperity in Malawi, 2004–2010 ..........................................................1 1.1. Snapshot of Poverty in Malawi ..................................................................................................................1 1.2. Where Are the Poor and Who Are They? ..................................................................................................5 1.2.1. Incidence of poverty and inequality across space ..........................................................................................5 1.2.2. Who are the poor? ...................................................................................................................................8 1.3. Shared Prosperity ..................................................................................................................................... 10 1.3.1. Incidence of growth of consumption and monetary poverty ......................................................................... 10 1.3.2. High and persistent -

Malawi Coverage Survey 2017

Malawi Coverage Survey 2017 Measuring treatment coverage for schistosomiasis and soil transmitted helminths with preventive chemotherapy 1 Contents Contents .................................................................................................................................................. 2 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 4 Background to the Coverage Survey ....................................................................................................... 4 Schistosomiasis and STH in Malawi .................................................................................................... 5 Previous mapping ............................................................................................................................... 5 Treatment History ............................................................................................................................... 5 Previous Coverage Surveys ................................................................................................................. 6 2012 ................................................................................................................................................ 6 2014 ................................................................................................................................................ 6 2016 ............................................................................................................................................... -

ISO 3166-2 NEWSLETTER Changes in the List of Subdivision Names And

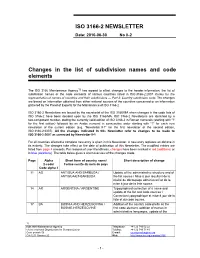

ISO 3166-2 NEWSLETTER Date: 2010-06-30 No II-2 Changes in the list of subdivision names and code elements The ISO 3166 Maintenance Agency1) has agreed to effect changes to the header information, the list of subdivision names or the code elements of various countries listed in ISO 3166-2:2007 Codes for the representation of names of countries and their subdivisions — Part 2: Country subdivision code. The changes are based on information obtained from either national sources of the countries concerned or on information gathered by the Panel of Experts for the Maintenance of ISO 3166-2. ISO 3166-2 Newsletters are issued by the secretariat of the ISO 3166/MA when changes in the code lists of ISO 3166-2 have been decided upon by the ISO 3166/MA. ISO 3166-2 Newsletters are identified by a two-component number, stating the currently valid edition of ISO 3166-2 in Roman numerals (starting with "I" for the first edition) followed by an Arabic numeral in consecutive order starting with "1" for each new newsletter of the current edition (e.g. "Newsletter II-1" for the first newsletter of the second edition, ISO 3166-2:2007). All the changes indicated in this Newsletter refer to changes to be made to ISO 3166-2:2007 as corrected by Newsletter II-1. For all countries affected a complete new entry is given in this Newsletter. A new entry replaces an old one in its entirety. The changes take effect on the date of publication of this Newsletter. The modified entries are listed from page 4 onwards. -

Agriculture and the Socio- Economic Environment

E4362 v1 REPUBLIC OF MALAWI Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Ministry of Agriculture and Food Security Agricultural Sector Wide Approach – Support Project – Additional Financing Public Disclosure Authorized ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL MANAGEMENT FRAMEWORK (ESMF) DRAFT FINAL REPORT Ministry of Agriculture and Food Security Capital Hill P O Box 30134 Public Disclosure Authorized Capital City Lilongwe 3 MALAWI January 2012 Updated November 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ........................................................................................................... ii LIST OF ACRONYMS ............................................................................................................. v EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ..................................................................................................... vii CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND ............................................ 13 1.1 The National Context .............................................................................................. 13 1.2 The Agriculture Sector ........................................................................................... 13 1.3 The Agricultural Sector Wide Approach Support Project (ASWAp-SP) ......... 14 1.3.1 Project Development Objectives ............................................................................. 15 1.3.2 Programme Components and additional activities................................................. 16 1.3.3 Description of sub-components.............................................................................. -

FEWS NET Malawi Enhanced Market Analysis September 2018

FEWS NET Malawi Enhanced Market Analysis 2018 MALAWI ENHANCED MARKET ANALYSIS SEPTEMBER 2018 This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by Chemonics International Inc. for the Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS NET), contract number AID-OAA-I-12-00006. The authors’Famine views Early expressed Warning inSystem this publications Network do not necessarily reflect the views of the 1 United States Agency for International Development or the United States government. FEWS NET Malawi Enhanced Market Analysis 2018 About FEWS NET Created in response to the 1984 famines in East and West Africa, the Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS NET) provides early warning and integrated, forward-looking analysis of the many factors that contribute to food insecurity. FEWS NET aims to inform decision makers and contribute to their emergency response planning; support partners in conducting early warning analysis and forecasting; and provide technical assistance to partner-led initiatives. To learn more about the FEWS NET project, please visit www.fews.net. Disclaimer This publication was prepared under the United States Agency for International Development Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS NET) Indefinite Quantity Contract, AID-OAA-I-12-00006. The authors’ views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States government. Acknowledgements FEWS NET gratefully acknowledges the network of partners in Malawi who contributed their time, analysis, and data to make this report possible. Recommended Citation FEWS NET. 2018. Malawi Enhanced Market Analysis. Washington, DC: FEWS NET. -

The Decline in Mine Migrancy and Increase in Informal Labour Migration from Northern Malawi to South Africa, 1970S-1980S1

Mine migrancy and... informal labour migration... northern Malawi to South Africa, New Contree, 79, December 2017, pp. 65-85 The decline in mine migrancy and increase in informal labour migration from northern Malawi to South Africa, 1970s-1980s1 Harvey C Chidoba Banda University of the Witwatersrand [email protected] Abstract International labour migration from Malawi to South Africa is more than a century old. Malawian migrants started going to, largely, South African mines around the 1870s and 1880s following the establishment of diamond and gold mines. This migration took two forms: formal migration to the mines and informal migration to different sectors of the economy. Formal migration, initially masterminded by the Witwatersrand Native Labour Association (WNLA) and later by The Employment Bureau of Africa (TEBA), declined in the 1970s and finally collapsed in the 1980s. This article critiques this decline in mine labour migrancy by analysing the developments in the 1970s and 1980s. Contrary to previous scholarship, the article centrally argues that the decline could be traced from as early as the 1960s and that the 1974 plane crash incident and the 1987 HIV wrangle between Malawi and South Africa merely brought mine migrancy to a grinding halt. The article largely uses archival and oral sources. On the use of the latter, interviews were conducted among migrants and ex-migrants from Mzimba and Nkhata-Bay, the two districts historically associated with labour migration to South Africa from northern Malawi. Keywords: Migrancy; Formal migration; Informal migration; Selufu; Wenela; Theba; Internalisation. Introduction This article examines the decline of mine migrancy from northern Malawi districts of Mzimba and Nkhata-Bay to the South African mines in the 1970s and 1980s. -

Political Salience of Cultural Difference: Why Chewas and Tumbukas Are Allies in Zambia and Adversaries in Malawi DANIEL N

American Political Science Review Vol. 98, No. 4 November 2004 The Political Salience of Cultural Difference: Why Chewas and Tumbukas Are Allies in Zambia and Adversaries in Malawi DANIEL N. POSNER University of California, Los Angeles his paper explores the conditions under which cultural cleavages become politically salient. It does so by taking advantage of the natural experiment afforded by the division of the Chewa T and Tumbuka peoples by the border between Zambia and Malawi. I document that, while the objective cultural differences between Chewas and Tumbukas on both sides of the border are identical, the political salience of the division between these communities is altogether different. I argue that this difference stems from the different sizes of the Chewa and Tumbuka communities in each country relative to each country’s national political arena. In Malawi, Chewas and Tumbukas are each large groups vis- a-vis` the country as a whole and, thus, serve as viable bases for political coalition-building. In Zambia, Chewas and Tumbukas are small relative to the country as a whole and, thus, not useful to mobilize as bases of political support. The analysis suggests that the political salience of a cultural cleavage depends not on the nature of the cleavage itself (since it is identical in both countries) but on the sizes of the groups it defines and whether or not they will be useful vehicles for political competition. ultural differences are claimed to be at the Why do some cultural differences matter for politics root of many of the world’s conflicts, both and others not? Cwithin states (Gurr 2000; Horowitz 1985, 2001; To pose this question is not, of course, to deny that Lake and Rothchild 1998) and among them political differences sometimes do follow cultural lines. -

Malawi Fourth Integrated Household Survey (IHS4) 2016-2017 Basic Information Document

Malawi Fourth Integrated Household Survey (IHS4) 2016-2017 Basic Information Document November 2017 National Statistical Office, P.O Box 333 Zomba Malawi www.nso.malawi.net ACRONYMS ADD Agricultural Development Division ADMARC Agricultural Development and Marketing Corporation CAPI Computer Assisted Personal Interviewing DFID Department for International Development EA Enumeration Area FAO Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations GTZ German Development Corporation IFAD International Fund for Agricultural Development IHPS Integrated Household Panel Survey 2013 IHS1 First Integrated Household Survey 1997-1998 IHS3 Second Integrated Household Survey 2004-2005 IHS3 Third Integrated Household Survey 2010-2011 IHS4 Fourth Integrated Household Survey 2016-2017 LSMS Living Standards Measurement Study LSMS-ISA LSMS–Integrated Surveys on Agriculture MCC Millennium Challenge Corporation MGDS Malawi Growth and Development Strategy MDG Millennium Development Goal MK Malawi Kwacha NACAL National Census of Agriculture and Livestock NSO National Statistical Office of Malawi PHC Population and Housing Census PSU Primary Sampling Unit SDG Sustainable Development Goal TA Traditional Authority WFP World Food Programme WMS Welfare Monitoring Survey 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.00 INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................................... 4 2.00 SURVEY DESIGN ....................................................................................................................... -

Project Summary……………………………………………………………………………...Iv Results Based Logical Framework…………………….……………………………………...Vi Project Time Frame………………………………………………………………………….Viii

AFRICAN DEVELOPMENT BANK GROUP TANZANIA/MALAWI: STRENGTHENING TRANSBOUNDARY COOPERATION AND INTEGRATED NATURAL RESOURCES MANAGEMENT IN THE SONGWE RIVER BASIN RDGS/AHWS/PGCL May 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS Currency Equivalents…………………………………………………………….…………….i Acronyms and Abbreviations………………………………………………………………….ii Loan Information…………………………………..…………………………………………iii Project Summary……………………………………………………………………………...iv Results Based Logical Framework…………………….……………………………………...vi Project Time Frame………………………………………………………………………….viii 1. STRATEGIC THRUST & RATIONALE .......................................................................... 8 1.1. Project linkages with country strategy and objectives ................................................ 8 1.2. Rationale for Bank’s involvement............................................................................... 9 1.3. Donors coordination .................................................................................................... 4 2. PROJECT DESCRIPTION ................................................................................................ 6 2.1. Project Description ...................................................................................................... 6 2.2. Technical solution retained and other alternatives explored ..................................... 13 2.3. Project type .................................................................................................................. 7 2.4. Project cost and financing arrangements .................................................................... -

Mapping Protocol Integrated Control of Schistosomiasis and Intestinal Helminths in Sub-Saharan Africa (ICOSA)

Malawi MoH/ICOSA: Mapping Protocol Integrated Control of Schistosomiasis and Intestinal Helminths in sub-Saharan Africa (ICOSA) Programme Manager: SCI Country Co-ordinator: Mr Samuel Jemu Dr Charlotte Gower Ministry of Health SCI PO Box 30377 Department of Infectious Disease Epidemiology Lilongwe 3 Imperial College London (St Mary’s Campus) MALAWI Norfolk Place London W2 1PG, UK Tel: +265 999 048 269 Tel: +44 207 594 3626 Email: [email protected] [email protected] Technical Advisor: Biostatistician: Dr Narcis Kabatereine Dr Ben Styles VCD, Ministry of Health SCI 15 Bombo Road Department of Infectious Disease Epidemiology PO Box 1661 Imperial College London (St Mary’s Campus) Kampala, Uganda Norfolk Place London W2 1PG, UK Tel: +256 Tel: +44 207 594 3474 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] This protocol was produced using material from several individuals within the ICOSA consortium. ABSTRACT Schistosomiasis is a highly focalised disease which has been shown to have hugely varied distribution within a small radius. Therefore clear mapping data to establish regions of high and low prevalence is essential in order to assign a treatment plan that reduces worm burden significantly and decreases morbidity associated with schistosomiasis and soil transmitted helminths. In order to produce the most cost-effective, yet sufficiently detailed mapping strategy, a number of alternative mapping methodologies have been considered. The proposed strategy, in our opinion, is a time efficient and cost-effective method which is also sensitive to budget limitations and the potential economical and logistical strains placed on the Ministry. We believe this protocol will reduce costs without losing specificity for directed treatment to schools with the highest burden of disease.