Vivaldi and the Siciliana: Towards a Critical Appraisal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Music the Music-To-Go Trio Wedding Guide Go Trio Wedding

The MusicMusic----ToToToTo----GoGo Trio Wedding Guide Processionals Trumpet Voluntary.................................................................................Clarke Wedding March.....................................................................................Wagner Jesu, Joy of Man’s Desiring...................................................................... Bach Te Deum Prelude.......................................................................... Charpentier Canon ................................................................................................. Pachelbel Air from Water Music............................................................................. Handel Sleepers Awake.......................................................................................... Bach Sheep May Safely Graze........................................................................... Bach Air on the G String................................................................................... Bach Winter (Largo) from The Four Seasons ..................................................Vivaldi MidMid----CeremonyCeremony Music Meditations, Candle Lightings, Presentations etc. Ave Maria.............................................................................................Schubert Ave Maria...................................................................................Bach-Gounod Arioso......................................................................................................... Bach Meditation from Thaïs ......................................................................Massenet -

Handel's Sacred Music

The Cambridge Companion to HANDEL Edited byD oNAtD BURROWS Professor of Music, The Open University, Milton Keynes CATvTNnIDGE UNTVERSITY PRESS 165 Ha; strings, a 1708 fbr 1l Handel's sacred music extended written to Graydon Beeks quake on sary of th; The m< Jesus rath Handel was involved in the composition of sacred music throughout his strings. Tl career, although it was rarely the focal point of his activities. Only during compositi the brief period in 1702-3 when he was organist for the Cathedral in Cardinal ( Halle did he hold a church job which required regular weekly duties and, one of FIi since the cathedral congregation was Calvinist, these duties did not Several m include composing much (if any) concerted music. Virtually all of his Esther (H\ sacred music was written for specific events and liturgies, and the choice moYemenr of Handel to compose these works was dictated by his connections with The Ror specific patrons. Handel's sacred music falls into groups of works which of Vespers were written for similar forces and occasions, and will be discussed in followed b terms of those groups in this chapter. or feast, ar During his period of study with Zachow in Halle Handel must have followed b written some music for services at the Marktkirche or the Cathedral, but porarl, Ro no examples survive.l His earliest extant work is the F major setting of chanted, br Psalm 113, Laudate pueri (H\41/ 236),2 for solo soprano and strings. The tradition o autograph is on a type of paper that was available in Hamburg, and he up-to-date may have -

Scholarly Program Notes of Selected Trumpet Repertoire Jeanne Millikin Jeanne Millikin, [email protected]

Southern Illinois University Carbondale OpenSIUC Research Papers Graduate School 2011 Scholarly Program Notes of Selected Trumpet Repertoire Jeanne Millikin Jeanne Millikin, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/gs_rp Recommended Citation Millikin, Jeanne, "Scholarly Program Notes of Selected Trumpet Repertoire" (2011). Research Papers. Paper 157. http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/gs_rp/157 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at OpenSIUC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Research Papers by an authorized administrator of OpenSIUC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SCHOLARLY PROGRAM NOTES OF SELECTED TRUMPET REPERTOIRE BY Jeanne Millikin B.M., Southern Illinois University Carbondale, 2008 Research Submitted in Partial Fulfillment for MASTER OF MUSIC Department of Music in the Graduate School Southern Illinois University Carbondale August 2011 RESEARCH PAPER APPROVAL SCHOLARLY PROGRAM NOTES ON SELECTED TRUMPET REPERTOIRE By Jeanne Millikin A Research Paper Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Masters of Music in the field of Music Performance Approved by: Dr. Robert Allison, Chair Mr. Edward Benyas Dr. Richard Kelley Graduate School Southern Illinois University Carbondale July 11, 2011 AN ABSTRACT OF THE RESEARCH PAPER OF JEANNE MILLIKIN, for the Master of Music degree in TRUMPET PERFORMANCE, presented on APRIL 7, 2011, at Southern Illinois University Carbondale. TITLE: SCHOLARLY PROGRAM NOTES FOR SELECTED TRUMPET REPERTOIRE MAJOR PROFESSOR: Dr. Robert Allison The purpose of this research paper is to provide insight and research to five selected compositions in which the trumpet plays a soloistic or significant role. -

2257-AV-Venice by Night Digi

VENICE BY NIGHT ALBINONI · LOTTI POLLAROLO · PORTA VERACINI · VIVALDI LA SERENISSIMA ADRIAN CHANDLER MHAIRI LAWSON SOPRANO SIMON MUNDAY TRUMPET PETER WHELAN BASSOON ALBINONI · LOTTI · POLLAROLO · PORTA · VERACINI · VIVALDI VENICE BY NIGHT Arriving by Gondola Antonio Vivaldi 1678–1741 Antonio Lotti c.1667–1740 Concerto for bassoon, Alma ride exulta mortalis * Anon. c.1730 strings & continuo in C RV477 Motet for soprano, strings & continuo 1 Si la gondola avere 3:40 8 I. Allegro 3:50 e I. Aria – Allegro: Alma ride for soprano, violin and theorbo 9 II. Largo 3:56 exulta mortalis 4:38 0 III. Allegro 3:34 r II. Recitativo: Annuntiemur igitur 0:50 A Private Concert 11:20 t III. Ritornello – Adagio 0:39 z IV. Aria – Adagio: Venite ad nos 4:29 Carlo Francesco Pollarolo c.1653–1723 Journey by Gondola u V. Alleluja 1:52 Sinfonia to La vendetta d’amore 12:28 for trumpet, strings & continuo in C * Anon. c.1730 2 I. Allegro assai 1:32 q Cara Nina el bon to sesto * 2:00 Serenata 3 II. Largo 0:31 for soprano & guitar 4 III. Spiritoso 1:07 Tomaso Albinoni 3:10 Sinfonia to Il nome glorioso Music for Compline in terra, santificato in cielo Tomaso Albinoni 1671–1751 for trumpet, strings & continuo in C Sinfonia for strings & continuo Francesco Maria Veracini 1690–1768 i I. Allegro 2:09 in G minor Si 7 w Fuga, o capriccio con o II. Adagio 0:51 5 I. Allegro 2:17 quattro soggetti * 3:05 p III. Allegro 1:20 6 II. Larghetto è sempre piano 1:27 in D minor for strings & continuo 4:20 7 III. -

Karel Keldermans

Upcoming Events Faculty Recital: Julia Bullard, viola Friday, April 12, 6 p.m. Davis Hall, GBPAC UNI Opera Presents: Serse Friday-Saturday, April 12-13, 7:30 p.m. Bengtson Auditorium, Russell Hall UNI Jazz Band Three Monday, April 15, 7:30 p.m. Bengtson Auditorium, Russell Hall The School of Music Calendar of Events is available online at music.uni.edu/events. To receive a hardcopy, please call 319-273-2028. Karel Keldermans, carillonneur In consideration of the performers and other members of the audience, please enter or leave a performance at the end of a composition. Cameras and recording equipment are not permitted. Please turn off all electronic devices, and be sure that all emergency contact cell phones and pagers are set to silent or vibrate. In the event of an emergency, please use the exit nearest to you. Please contact the usher staff if you need assistance. This event is free to all UNI students, courtesy of the Panther Pass Program. Performances like this are made possible through private support from patrons like you! Please consider contributing to School of Music scholarships or guest artist programs. Call 319-273-3915 or visit www.uni.edu/music to make your gift. Thursday, April 11, 2019, 12 p.m. UNI Campanile Program About our Guest Artist 1. Concerto Grosso . .Ronald Barnes KAREL KELDERMANS is one of the pre-eminent carillonneurs a. Largo (1927-1997) in North America. Karel has been Carillonneur for b. Siciliana Concordia Seminary in St. Louis, Missouri since 2000. He c. Pollacca retired in 2012 from the position of full-time Carillonneur for the Springfield Park District in Springfield, Illinois, where he 2. -

A Countertenor's Reference Guide to Operatic Repertoire

A COUNTERTENOR’S REFERENCE GUIDE TO OPERATIC REPERTOIRE Brad Morris A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC May 2019 Committee: Christopher Scholl, Advisor Kevin Bylsma Eftychia Papanikolaou © 2019 Brad Morris All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Christopher Scholl, Advisor There are few resources available for countertenors to find operatic repertoire. The purpose of the thesis is to provide an operatic repertoire guide for countertenors, and teachers with countertenors as students. Arias were selected based on the premise that the original singer was a castrato, the original singer was a countertenor, or the role is commonly performed by countertenors of today. Information about the composer, information about the opera, and the pedagogical significance of each aria is listed within each section. Study sheets are provided after each aria to list additional resources for countertenors and teachers with countertenors as students. It is the goal that any countertenor or male soprano can find usable repertoire in this guide. iv I dedicate this thesis to all of the music educators who encouraged me on my countertenor journey and who pushed me to find my own path in this field. v PREFACE One of the hardships while working on my Master of Music degree was determining the lack of resources available to countertenors. While there are opera repertoire books for sopranos, mezzo-sopranos, tenors, baritones, and basses, none is readily available for countertenors. Although there are online resources, it requires a great deal of research to verify the validity of those sources. -

Download Booklet

Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment Monteverdi Vespers oae released and really cemented my path on the road towards Monteverdi often sets the text in that way. I took ‘early music’. Ever since then I have wanted to the decision therefore to blend low tenors with direct performances of it and play it as many times high baritones, low baritones with basses, high as possible. It is a work of such beauty and depth tenors with countertenors etc to create more of that such a wide variety of interpretations can be the sound of a choir that can sing both high and Claudio Monteverdi made of it. I would like to explain briefly some of low within its partbooks. Vespers of the Blessed Virgin, 1610 the choices that I made in preparing for this: When we performed this as a concert, Monteverdi’s publication appears as part- I added in liturgical plainchant as I strongly ROBERT HOWARTH Director books and not as a full score. Many editors believe that Monteverdi never conceived these have undertaken the task of putting together as concert pieces but only ever to be heard in the a performing edition and I’m sure they will all church as part of a service, therefore the Psalms acknowledge that none of them are perfect. What would have been preceded by antiphons relevant lies within these books are dark mysterious codes to the day. These do affect the Psalm and the about how to interpret the music. Once an editor context in which they are heard. As we are now has made decisions on your behalf, it is difficult removing ourselves by one step and presenting not to do their version. -

Georg Friedrich Händel

Georg Friedrich Händel Georg Friedrich Händel (pronunciación alemana: [ ˈgeːɔɐk ˈfʁiːdʁɪç ˈhɛn.dəl ]; Halle, Alemania, 23 de febrero de 1685 – Londres, 14 de abril de 1759) fue un compositor alemán, posteriormente nacionalizado británico, considerado una de las cumbres del Barroco y uno de los más influyentes compositores de la música occidental y universal.1 En la historia de la música, es el primer compositor moderno2 en haber adaptado y enfocado su música para satisfacer los gustos y necesidades del público,2 en vez de los de la nobleza y de los mecenas, como era habitual. Considerado el sucesor y continuador de Henry Purcell,3 marcó toda una era en la música inglesa4 siendo el compositor más importante entre Purcell y Elgar en Inglaterra. Es el primer gran maestro de la música basada en la técnica de la homofonía5 y el más grande dentro del ámbito de los géneros de la ópera seria italiana6 y el oratorio.7 Halle y Hamburgo (1685-1706)[editar] Nació en la ciudad de Halle, ubicada en el centro este de la actual Alemania. Su padre era barbero y cirujano de prestigio y había decidido que su hijo sería abogado, pero cuando observó el interés de Händel por la música, la cual estudiaba y practicaba en secreto, cambió de idea y se mostró dispuesto a pagarle los estudios de música. De esta forma, Händel se convirtió en alumno del principal organista de Halle, Friedrich Wilhelm Zachau, quien le enseñó a tocar el órgano, el clave y el oboe. A la edad de 17 años lo nombraron organista de la catedral calvinista de Halle. -

Raymond Monelle. 2006. the Musical Topic: Hunt, Military, and Pastoral

Raymond Monelle. 2006. The Musical Topic: Hunt, Military, and Pastoral. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press. Reviewed by Andrew Haringer Raymond Monelle, who passed away earlier this year, was something of an anomaly in the academic community. As far as I am aware, he is the only musicologist to have a pop song written in his honor: "Keep in Sight of Raymond Monelle" by Canadian in die band Barcelona Pavilion. He was that rare breed of the true performer-scholar who remained active as a composer, jazz pianist, and conductor, nurturing the boyhood talents of now-prominent Scottish musicians Donald Runnicles and James MacMillan in the latter capacity. Following his retirement in 2002, he even wrote a novel about the adolescence of Alban Berg, which currently remains unpublished. l However, it is for his groundbreaking work in musical semiotics, and topic theory in particular, for which Dr. Monelle is most likely to be remem bered' and here too he deviated from the norm. Over the past two decades, he developed an approach to the study of music signification that was at once solidly grounded in the methodologies of the past, and yet refreshingly devoid of dogmatic prejudice and any pretense of quasi-scientific rigor. It was this judicious blend of a solid foundation and an adventurous spirit that ensured glowing reviews of Monelle's first two books by scholars of such different temperaments as Kofi Agawu (1994) and Susan McClary (2001).1t is therefore surprising that his third and, in my estimation, greatest book-The Musical Topic: Hunt, Military, and Pastoral-met with so little fanfare when it appeared four years ago. -

Early Music Influences in Paul Hindemith's Compositions for the Viola Domenico L

James Madison University JMU Scholarly Commons Dissertations The Graduate School Fall 2014 Early music influences in Paul Hindemith's Compositions for the Viola Domenico L. Trombetta James Madison University Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/diss201019 Part of the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Trombetta, Domenico L., "Early music influences in Paul Hindemith's Compositions for the Viola" (2014). Dissertations. 5. https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/diss201019/5 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the The Graduate School at JMU Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of JMU Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Early Music Influences in Paul Hindemith’s Compositions for the Viola Domenico Luca Trombetta A thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty of JAMES MADISON UNIVERSITY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts School of Music December 2014 To my wife Adelaide ii CONTENTS DEDICATION…………………………………………………………………………….ii LIST OF MUSICAL EXAMPLES……………………………………………………….iv LIST OF FIGURES………………………………………………………………………vi ABSTRACT……………………………………………………………………………..vii INTRODUCTION………………………………………………………………………...1 I. The Origins of Hindemith’s Interest in Early Music………………………………….5 II. The Influence of Bach’s D-Minor Chaconne for Solo Violin on Hindemith’s Viola Sonatas op. 11, no.5 and op. 31, no.4………………………………………………..14 III. Viola Concerto Der Schwanendreher………………………………………………..23 IV. Trauermusik for Viola and Strings…………………………………………………..35 CONCLUSION…………………………………………………………………………..42 BIBLIOGRAPHY………………………………………………………………………..45 APPENDICES…………………………………………………………………………...48 A. Musical Examples B. Figures iii Musical Examples 1a Hindemith, Solo Viola Sonata Op. 11, No. 5, movt. IV (In Form und Zeitmass einer Passacaglia), Theme…………………............................................49 1b Bach, Chaconne, Theme………………………………………………………....49 1c Hindemith, Solo Viola Sonata Op. -

Antonio Lucio VIVALDI

AN IMPORTANT NOTE FROM Johnstone-Music ABOUT THE MAIN ARTICLE STARTING ON THE FOLLOWING PAGE: We are very pleased for you to have a copy of this article, which you may read, print or save on your computer. You are free to make any number of additional photocopies, for johnstone-music seeks no direct financial gain whatsoever from these articles; however, the name of THE AUTHOR must be clearly attributed if any document is re-produced. If you feel like sending any (hopefully favourable) comment about this, or indeed about the Johnstone-Music web in general, simply vis it the ‘Contact’ section of the site and leave a message with the details - we will be delighted to hear from you ! Una reseña breve sobre VIVALDI publicado por Músicos y Partituras Antonio Lucio VIVALDI Antonio Lucio Vivaldi (Venecia, 4 de marzo de 1678 - Viena, 28 de julio de 1741). Compositor del alto barroco, apodado il prete rosso ("el cura rojo" por ser sacerdote y pelirrojo). Compuso unas 770 obras, entre las cuales se cuentan 477 concerti y 46 óperas; especialmente conocido a nivel popular por ser el autor de Las cuatro estaciones. johnstone-music Biografia Vivaldi un gran compositor y violinista, su padre fue el violinista Giovanni Batista Vivaldi apodado Rossi (el Pelirrojo), fue miembro fundador del Sovvegno de’musicisti di Santa Cecilia, organización profesional de músicos venecianos, así mismo fue violinista en la orquesta de la basílica de San Marcos y en la del teatro de S. Giovanni Grisostomo., fue el primer maestro de vivaldi, otro de los cuales fue, probablemente, Giovanni Legrenzi. -

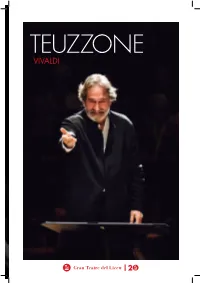

Teuzzone Vivaldi

TEUZZONE VIVALDI Fitxa / Ficha Vivaldi se’n va a la Xina / 11 41 Vivaldi se va a China Xavier Cester Repartiment / Reparto 12 Teuzzone o les meravelles 57 d’Antonio Vivaldi / Teuzzone o las maravillas Amb el teló abaixat / de Antonio Vivaldi 15 A telón bajado Manuel Forcano 21 Argument / Argumento 68 Cronologia / Cronología 33 English Synopsis 84 Biografies / Biografías x x Temporada 2016/17 Amb el suport del Departament de Cultura de la Generalitat de Catalunyai la Diputació de Barcelona TEUZZONE Òpera en tres actes. Llibret d’Apostolo Zeno. Música d’Antonio Vivaldi Ópera en tres actos. Libreto de Apostolo Zeno. Música de Antonio Vivaldi Estrenes / Estrenos Carnestoltes 1719: Estrena absoluta al Teatro Arciducale de Màntua / Estreno absoluto en el Teatro Arciducale de Mantua Estrena a Espanya / Estreno en España Febrer / Febrero 2017 Torn / Turno Tarifa 24 20.00 h G 8 25 18.00 h F 8 Durada total aproximada 3h 15m Uneix-te a la conversa / Únete a la conversación liceubarcelona.cat #TeuzzoneLiceu facebook.com/liceu @liceu_cat @liceu_opera_barcelona 12 pag. Repartiment / Reparto 13 Teuzzone, fill de l’emperador de Xina Paolo Lopez Teuzzone, hijo del emperador de China Zidiana, jove vídua de Troncone Marta Fumagalli Zidiana, joven viuda de Troncone Zelinda, princesa tàrtara Sonia Prina Zelinda, princesa tártara Sivenio, general del regne Furio Zanasi Sivenio, general del reino Cino, primer ministre Roberta Mameli Cino, primer ministro Egaro, capità de la guàrdia Aurelio Schiavoni Egaro, capitán de la guardia Troncone / Argonte, emperador Carlo Allemano de Xina / príncep tàrtar Troncone / Argonte, emperador de China / príncipe tártaro Direcció musical Jordi Savall Dirección musical Le Concert des Nations Concertino Manfredo Kraemer Sobretítols / Sobretítulos Glòria Nogué, Anabel Alenda 14 pag.