Pacific Americas Shorebird Conservation Strategy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Proxy Voting Guidelines Benchmark Policy Recommendations TITLE

UNITED STATES Proxy Voting Guidelines Benchmark Policy Recommendations TITLE Effective for Meetings on or after February 1, 2021 Published November 19, 2020 ISS GOVERNANCE .COM © 2020 | Institutional Shareholder Services and/or its affiliates UNITED STATES PROXY VOTING GUIDELINES TABLE OF CONTENTS Coverage ................................................................................................................................................................ 7 1. Board of Directors ......................................................................................................................................... 8 Voting on Director Nominees in Uncontested Elections ........................................................................................... 8 Independence ....................................................................................................................................................... 8 ISS Classification of Directors – U.S. ................................................................................................................. 9 Composition ........................................................................................................................................................ 11 Responsiveness ................................................................................................................................................... 12 Accountability .................................................................................................................................................... -

Discovery Park

Final Vegetation Management Plan Discovery Park Prepared for: Seattle Department of Parks and Recreation Seattle, Washington Prepared by: Bellevue, Washington March 5, 2002 Final Vegetation Management Plan Discovery Park Prepared for: Seattle Department of Parks and Recreation 100 Dexter Seattle, Washington 98109 Prepared by: 11820 Northup Way, Suite E300 Bellevue, Washington 98005-1946 425/822-1077 March 5, 2002 This document should be cited as: Jones & Stokes. 2001. Discovery Park. Final Vegetation Management Plan. March 5. (J&S 01383.01.) Bellevue, WA. Prepared for Seattle Department of Parks and Recreation, Seattle, WA. Table of Contents 1 INTRODUCTION AND APPROACH........................................................................................1 1.1 Introduction....................................................................................................................1 1.2 Approach .......................................................................................................................2 2 EXISTING CONDITIONS AND RECENT VEGETATION STUDIES ........................................3 2.1 A Brief Natural History of Discovery Park .........................................................................3 2.2 2001 Vegetation Inventory ...............................................................................................4 2.3 Results of Vegetation Inventory ........................................................................................4 2.3.1 Definitions ......................................................................................................4 -

Acoustic Monitoring of Night-Migrating Birds: a Progress Report

Acoustic Monitoring of Night-Migrating Birds: A Progress Report William R. Evans Kenneth V. Rosenberg Abstract—This paper discusses an emerging methodology that to give regular vocalizations in night migration are the vireos uses electronic technology to monitor vocalizations of night-migrat- (Vireonidae), flycatchers (Tyrannidae), and orioles (Icterinae). ing birds. On a good migration night in eastern North America, If a monitoring protocol is consistently maintained, an array thousands of call notes may be recorded from a single ground-based, of microphone stations can provide information on how the audio-recording station, and an array of recording stations across a species composition and number of vocal migrants vary across region may serve as a “recording net” to monitor a broad front of time and space. Such data have application for monitoring migration. Data from pilot studies in Florida, Texas, New York, and avian populations and identifying their migration routes. In British Columbia illustrate the potential of this technique to gather addition, detection and classification of distinctive call-types information that cannot be gathered by more conventional methods, is possible with computers (Mills 1995; Taylor 1995), thus such as mist-netting or diurnal counts. For example, the Texas information on bird populations might be gained automati- station detected a major migration of grassland sparrows, and a cally. In this paper, we summarize the current state of station in British Columbia detected hundreds of Swainson’s knowledge for identifying night-flight calls to species; present Thrushes; both phenomena were not detected with ground monitor- selected results from four ongoing studies that are monitoring ing efforts. -

Baja California's Sonoran Desert

Baja California’s Sonoran Desert By Debra Valov What is a Desert? It would be difficult to find any one description that scarce and sporadic, with an would fit all of the twenty or so deserts found on our annual average of 12-30 cm (4.7- planet because each one is a unique landscape. 12 inches). There are two rainy seasons, December- While an expanse of scorching hot sand dunes with March and July-September, with the northern the occasional palm oasis is the image that often peninsula dominated by winter rains and the south comes to mind for the word desert, in fact, only by summer rains. Some areas experience both about 10% of the world’s deserts are covered by seasons, while in other areas, such as parts of the sand dunes. The other 90% comprise a wide variety Gulf coast region, rain may fail for years on end. of landscapes, among these cactus covered plains, Permanent above-ground water reserves are scarce foggy coastal slopes, barren salt flats, and high- throughout most of the peninsula but ephemeral, altitude, snow-covered plateaus. However, one seasonal pools and rivers do appear after winter characteristic that all deserts share is aridity—any storms in the north or summer storms (hurricanes place that receives less than 10 inches (25 and thunderstorms—chubascos) in the south. There centimeters) of rain per year is generally considered are also a number of permanent oases, most often to be a desert and the world’s driest deserts average formed where aquifers (subterranean water) rise to less than 10 mm (3/8 in.) annually. -

Struggle for North America Prepare to Read

0120_wh09MODte_ch03s3_s.fm Page 120 Monday, June 4, 2007 10:26WH09MOD_se_CH03_S03_s.fm AM Page 120 Monday, April 9, 2007 10:44 AM Step-by-Step WITNESS HISTORY AUDIO SECTION 3 Instruction 3 A Piece of the Past In 1867, a Canadian farmer of English Objectives descent was cutting logs on his property As you teach this section, keep students with his fourteen-year-old son. As they focused on the following objectives to help used their oxen to pull away a large log, a them answer the Section Focus Question piece of turf came up to reveal a round, and master core content. 3 yellow object. The elaborately engraved 3 object they found, dated 1603, was an ■ Explain why the colony of New France astrolabe that had belonged to French grew slowly. explorer Samuel de Champlain. This ■ Analyze the establishment and growth astrolabe was a piece of the story of the of the English colonies. European exploration of Canada and the A statue of Samuel de Champlain French-British rivalry that followed. ■ Understand why Europeans competed holding up an astrolabe overlooks Focus Question How did European for power in North America and how the Ottawa River in Canada (right). their struggle affected Native Ameri- Champlain’s astrolabe appears struggles for power shape the North cans. above. American continent? Struggle for North America Prepare to Read Objectives In the 1600s, France, the Netherlands, England, and Sweden Build Background Knowledge L3 • Explain why the colony of New France grew joined Spain in settling North America. North America did not Given what they know about the ancient slowly. -

The Systematic Position of the Surfbird, Aphriza Virgata

THE SYSTEMATIC POSITION OF THE SURFBIRD, APHRIZA VIRGATA JOSEPH R. JEHL, JR. University of Michigan Museum of Zoology Ann Arbor, Michigan 48104 The taxonomic relationships of the Surfbird, ( 1884) elevated the tumstone-Surfbird unit Aphriza virgata, have long been one of the to family rank. But, although they stated (p. most controversial problems in shorebird clas- 126) that Aphrizu “agrees very closely” with sification. Although the species has been as- Arenaria, the only points of similarity men- signed to a monotypic family (Shufeldt 1888; tioned were “robust feet, without trace of web Ridgway 1919), most modern workers agree between toes, the well formed hind toe, and that it should be placed with the turnstones the strong claws; the toes with a lateral margin ( Arenaria spp. ) in the subfamily Arenariinae, forming a broad flat under surface.” These even though they have reached no consensuson differences are hardly sufficient to support the affinities of this subfamily. For example, familial differentiation, or even to suggest Lowe ( 1931), Peters ( 1934), Storer ( 1960), close generic relationship. and Wetmore (1965a) include the Arenariinae Coues (1884605) was uncertain about the in the Scolopacidae (sandpipers), whereas Surfbirds’ relationships. He called it “a re- Wetmore (1951) and the American Ornithol- markable isolated form, perhaps a plover and ogists ’ Union (1957) place it in the Charadri- connecting this family with the next [Haema- idae (plovers). The reasons for these diverg- topodidae] by close relationships with Strep- ent views have never been stated. However, it silas [Armaria], but with the hind toe as well seems that those assigning the Arenariinae to developed as usual in Sandpipers, and general the Charadriidae have relied heavily on their appearance rather sandpiper-like than plover- views of tumstone relationships, because schol- like. -

Birds of Chile a Photo Guide

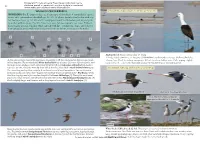

© Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be 88 distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical 89 means without prior written permission of the publisher. WALKING WATERBIRDS unmistakable, elegant wader; no similar species in Chile SHOREBIRDS For ID purposes there are 3 basic types of shorebirds: 6 ‘unmistakable’ species (avocet, stilt, oystercatchers, sheathbill; pp. 89–91); 13 plovers (mainly visual feeders with stop- start feeding actions; pp. 92–98); and 22 sandpipers (mainly tactile feeders, probing and pick- ing as they walk along; pp. 99–109). Most favor open habitats, typically near water. Different species readily associate together, which can help with ID—compare size, shape, and behavior of an unfamiliar species with other species you know (see below); voice can also be useful. 2 1 5 3 3 3 4 4 7 6 6 Andean Avocet Recurvirostra andina 45–48cm N Andes. Fairly common s. to Atacama (3700–4600m); rarely wanders to coast. Shallow saline lakes, At first glance, these shorebirds might seem impossible to ID, but it helps when different species as- adjacent bogs. Feeds by wading, sweeping its bill side to side in shallow water. Calls: ringing, slightly sociate together. The unmistakable White-backed Stilt left of center (1) is one reference point, and nasal wiek wiek…, and wehk. Ages/sexes similar, but female bill more strongly recurved. the large brown sandpiper with a decurved bill at far left is a Hudsonian Whimbrel (2), another reference for size. Thus, the 4 stocky, short-billed, standing shorebirds = Black-bellied Plovers (3). -

The All-Bird Bulletin

Advancing Integrated Bird Conservation in North America Spring 2014 Inside this issue: The All-Bird Bulletin Protecting Habitat for 4 the Buff-breasted Sandpiper in Bolivia The Neotropical Migratory Bird Conservation Conserving the “Jewels 6 Act (NMBCA): Thirteen Years of Hemispheric in the Crown” for Neotropical Migrants Bird Conservation Guy Foulks, Program Coordinator, Division of Bird Habitat Conservation, U.S. Fish and Bird Conservation in 8 Wildlife Service (USFWS) Costa Rica’s Agricultural Matrix In 2000, responding to alarming declines in many Neotropical migratory bird popu- Uruguayan Rice Fields 10 lations due to habitat loss and degradation, Congress passed the Neotropical Migra- as Wintering Habitat for tory Bird Conservation Act (NMBCA). The legislation created a unique funding Neotropical Shorebirds source to foster the cooperative conservation needed to sustain these species through all stages of their life cycles, which occur throughout the Western Hemi- Conserving Antigua’s 12 sphere. Since its first year of appropriations in 2002, the NMBCA has become in- Most Critical Bird strumental to migratory bird conservation Habitat in the Americas. Neotropical Migratory 14 Bird Conservation in the The mission of the North American Bird Heart of South America Conservation Initiative is to ensure that populations and habitats of North Ameri- Aros/Yaqui River Habi- 16 ca's birds are protected, restored, and en- tat Conservation hanced through coordinated efforts at in- ternational, national, regional, and local Strategic Conservation 18 levels, guided by sound science and effec- in the Appalachians of tive management. The NMBCA’s mission Southern Quebec is to achieve just this for over 380 Neo- tropical migratory bird species by provid- ...and more! Cerulean Warbler, a Neotropical migrant, is a ing conservation support within and be- USFWS Bird of Conservation Concern and listed as yond North America—to Latin America Vulnerable on the International Union for Conser- Coordination and editorial vation of Nature (IUCN) Red List. -

A Wood-Concrete Nest Box to Study Burrow-Nesting Petrels

Bedolla-Guzmán et al.: Wood-concrete nest boxes to study petrels 249 A WOOD-CONCRETE NEST BOX TO STUDY BURROW-NESTING PETRELS YULIANA BEDOLLA-GUZMÁN1,2, JUAN F. MASELLO1, ALFONSO AGUIRRE-MUÑOZ2 & PETRA QUILLFELDT1 1Department of Animal Ecology and Systematics, Justus Liebig University Giessen, Heinrich-Buff-Ring 38, 35392 Giessen, Germany 2Grupo de Ecología y Conservación de Islas, A.C., Moctezuma 836, Zona Centro, 22800, Ensenada, Baja California, Mexico ([email protected]) Received 6 July 2016, accepted 31 August 2016 Artificial nests have been a useful research and conservation tool is an extended period of bi-parental care, and parents return to feed for a variety of petrel species (Podolsky & Kress 1989, Priddel & the chick only at night (Brooke 2004). Carlile 1995, De León & Mínguez 2003, Bolton et al. 2004). They facilitate observation and provide easy access, reducing overall At San Benito West Island, 140 artificial wooden nests were disturbance to seabirds (Wilson 1986, Priddel & Carlile 1995) deployed by previous researchers, beginning in 1999, to study the and increasing data-collection efficiency (Wilson 1986). Likewise, breeding biology of Cassin’s Auklet Ptychoramphus aleuticus. restoration programs using artificial nests have improved the Auklets readily accepted and used the nest boxes. In the first year, number of potential nest sites, breeding success (Priddel & Carlile the occupancy rate was 30%, increasing to 80% in the fifth year 1995, De León & Mínguez 2003, Bolton et al. 2004, Bried et al. (Shaye Wolf, pers. comm.). At San Benito, auklets breed earlier 2009, McIver et al. 2016) and adult survival rates (Libois et al. -

Mummies and Mummification Practices in the Southern and Southwestern United States Mahmoud Y

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Karl Reinhard Papers/Publications Natural Resources, School of 1998 Mummies and mummification practices in the southern and southwestern United States Mahmoud Y. El-Najjar Yarmouk University, Irbid, Jordan Thomas M. J. Mulinski Chicago, Illinois Karl Reinhard University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/natresreinhard El-Najjar, Mahmoud Y.; Mulinski, Thomas M. J.; and Reinhard, Karl, "Mummies and mummification practices in the southern and southwestern United States" (1998). Karl Reinhard Papers/Publications. 13. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/natresreinhard/13 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Natural Resources, School of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Karl Reinhard Papers/Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Published in MUMMIES, DISEASE & ANCIENT CULTURES, Second Edition, ed. Aidan Cockburn, Eve Cockburn, and Theodore A. Reyman. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998. 7 pp. 121–137. Copyright © 1998 Cambridge University Press. Used by permission. Mummies and mummification practices in the southern and southwestern United States MAHMOUD Y. EL-NAJJAR, THOMAS M.J. MULINSKI AND KARL J. REINHARD Mummification was not intentional for most North American prehistoric cultures. Natural mummification occurred in the dry areas ofNorth America, where mummies have been recovered from rock shelters, caves, and over hangs. In these places, corpses desiccated and spontaneously mummified. In North America, mummies are recovered from four main regions: the south ern and southwestern United States, the Aleutian Islands, and the Ozark Mountains ofArkansas. -

Chapter 8 Migration Studies

Chapter 8 Migration Studies 100 Migration Studies Overview Theme he Pacific Flyway is a route taken by migratory birds during flights between breeding grounds in the north and wintering grounds in the south. Steigerwald Lake National Wildlife Refuge plays an important role in migration by providing birds with a protected resting area during their arduous journey. Migration makes it possible for birds to benefit the most from favorable weather conditions; they breed and feed in the north during the summer and rest and feed in the warmer south during the winter. This pattern is called return migration — the most common type of migration by birds. Through a variety of activities, students will learn about the factors and hazards of bird migration on the Pacific Flyway. Background The migration of birds usually refers to their regular flights between summer and winter homes. Some birds migrate thousands of miles, while others may travel less than a hundred miles. This seasonal movement has long been a mystery to humans. Aristotle, the naturalist and philosopher of ancient Greece, noticed that cranes, pelicans, geese, swans, doves, and many other birds moved to warmer places for the winter. Like others of times past, he proposed theories that were widely accepted for hundreds of years. One of his theories was that many birds spent the winter sleeping in hollow trees, caves, or beneath the mud in marshes. 101 Through natural selection, migration evolved as an advantageous behavior. Birds migrate north to nest and breed because the competition for food and space is substantially lower there. In addition, during the summer months the food supply is considerably better in many northern climates (e.g., Arctic regions). -

List of Species Likely to Benefit from Marine Protected Areas in The

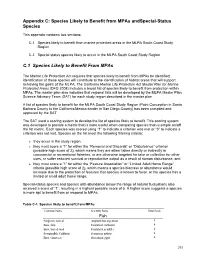

Appendix C: Species Likely to Benefit from MPAs andSpecial-Status Species This appendix contains two sections: C.1 Species likely to benefit from marine protected areas in the MLPA South Coast Study Region C.2 Special status species likely to occur in the MLPA South Coast Study Region C.1 Species Likely to Benefit From MPAs The Marine Life Protection Act requires that species likely to benefit from MPAs be identified; identification of these species will contribute to the identification of habitat areas that will support achieving the goals of the MLPA. The California Marine Life Protection Act Master Plan for Marine Protected Areas (DFG 2008) includes a broad list of species likely to benefit from protection within MPAs. The master plan also indicates that regional lists will be developed by the MLPA Master Plan Science Advisory Team (SAT) for each study region described in the master plan. A list of species likely to benefit for the MLPA South Coast Study Region (Point Conception in Santa Barbara County to the California/Mexico border in San Diego County) has been compiled and approved by the SAT. The SAT used a scoring system to develop the list of species likely to benefit. This scoring system was developed to provide a metric that is more useful when comparing species than a simple on/off the list metric. Each species was scored using “1” to indicate a criterion was met or “0” to indicate a criterion was not met. Species on the list meet the following filtering criteria: they occur in the study region, they must score a “1” for either