How Many Ways to Craft a Cofactor?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Flavin-Containing Monooxygenases: Mutations, Disease and Drug Response Phillips, IR; Shephard, EA

Flavin-containing monooxygenases: mutations, disease and drug response Phillips, IR; Shephard, EA For additional information about this publication click this link. http://qmro.qmul.ac.uk/jspui/handle/123456789/1015 Information about this research object was correct at the time of download; we occasionally make corrections to records, please therefore check the published record when citing. For more information contact [email protected] Flavin-containing monooxygenases: mutations, disease and drug response Ian R. Phillips1 and Elizabeth A. Shephard2 1School of Biological and Chemical Sciences, Queen Mary, University of London, Mile End Road, London E1 4NS, UK 2Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, University College London, Gower Street, London WC1E 6BT, UK Corresponding author: Shephard, E.A. ([email protected]). and, thus, contribute to drug development. This review Flavin-containing monooxygenases (FMOs) metabolize considers the role of FMOs and their genetic variants in numerous foreign chemicals, including drugs, pesticides disease and drug response. and dietary components and, thus, mediate interactions between humans and their chemical environment. We Mechanism and structure describe the mechanism of action of FMOs and insights For catalysis FMOs require flavin adenine dinucleotide gained from the structure of yeast FMO. We then (FAD) as a prosthetic group, NADPH as a cofactor and concentrate on the three FMOs (FMOs 1, 2 and 3) that are molecular oxygen as a cosubstrate [5,6]. In contrast to most important for metabolism of foreign chemicals in CYPs FMOs accept reducing equivalents directly from humans, focusing on the role of the FMOs and their genetic NADPH and, thus, do not require accessory proteins. -

Citric Acid Cycle

CHEM464 / Medh, J.D. The Citric Acid Cycle Citric Acid Cycle: Central Role in Catabolism • Stage II of catabolism involves the conversion of carbohydrates, fats and aminoacids into acetylCoA • In aerobic organisms, citric acid cycle makes up the final stage of catabolism when acetyl CoA is completely oxidized to CO2. • Also called Krebs cycle or tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle. • It is a central integrative pathway that harvests chemical energy from biological fuel in the form of electrons in NADH and FADH2 (oxidation is loss of electrons). • NADH and FADH2 transfer electrons via the electron transport chain to final electron acceptor, O2, to form H2O. Entry of Pyruvate into the TCA cycle • Pyruvate is formed in the cytosol as a product of glycolysis • For entry into the TCA cycle, it has to be converted to Acetyl CoA. • Oxidation of pyruvate to acetyl CoA is catalyzed by the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex in the mitochondria • Mitochondria consist of inner and outer membranes and the matrix • Enzymes of the PDH complex and the TCA cycle (except succinate dehydrogenase) are in the matrix • Pyruvate translocase is an antiporter present in the inner mitochondrial membrane that allows entry of a molecule of pyruvate in exchange for a hydroxide ion. 1 CHEM464 / Medh, J.D. The Citric Acid Cycle The Pyruvate Dehydrogenase (PDH) complex • The PDH complex consists of 3 enzymes. They are: pyruvate dehydrogenase (E1), Dihydrolipoyl transacetylase (E2) and dihydrolipoyl dehydrogenase (E3). • It has 5 cofactors: CoASH, NAD+, lipoamide, TPP and FAD. CoASH and NAD+ participate stoichiometrically in the reaction, the other 3 cofactors have catalytic functions. -

Cofactor Strap Regulates Oxidative Phosphorylation and Mitochondrial P53 Activity Through ATP Synthase

Cell Death and Differentiation (2015) 22, 156–163 & 2015 Macmillan Publishers Limited All rights reserved 1350-9047/15 www.nature.com/cdd Cofactor Strap regulates oxidative phosphorylation and mitochondrial p53 activity through ATP synthase S Maniam1,4, AS Coutts1,4, MR Stratford2, J McGouran3, B Kessler3 and NB La Thangue*,1 Metabolic reprogramming is a hallmark of cancer cells. Strap (stress-responsive activator of p300) is a novel TPR motif OB-fold protein that contributes to p53 transcriptional activation. We show here that, in addition to its established transcriptional role, Strap is localised at mitochondria where one of its key interaction partners is ATP synthase. Significantly, the interaction between Strap and ATP synthase downregulates mitochondrial ATP production. Under glucose-limiting conditions, cancer cells are sensitised by mitochondrial Strap to apoptosis, which is rescued by supplementing cells with an extracellular source of ATP. Furthermore, Strap augments the apoptotic effects of mitochondrial p53. These findings define Strap as a dual regulator of cellular reprogramming: first as a nuclear transcription cofactor and second in the direct regulation of mitochondrial respiration. Cell Death and Differentiation (2015) 22, 156–163; doi:10.1038/cdd.2014.135; published online 29 August 2014 An established characteristic of tumour cells is their under- model whereby Strap unfolds to become more accessible lying metabolic changes.1 Early observations that during the DNA-damage response.12 tumour cells had persistently high -

Novel Derivatives of Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide (NAD) and Their Biological Evaluation Against NAD- Consuming Enzymes

Novel derivatives of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD) and their biological evaluation against NAD- Consuming Enzymes Giulia Pergolizzi University of East Anglia School of Pharmacy Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy July, 2012 © This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with the author and that use of any information derived there from must be in accordance with current UK Copyright Law. In addition, any quotation or extract must include full attribution. ABSTRACT Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (β-NAD+) is a primary metabolite involved in fundamental biological processes. Its molecular structure with characteristic functional groups, such as the quaternary nitrogen of the nicotinamide ring, and the two high- energy pyrophosphate and nicotinamide N-glycosidic bonds, allows it to undergo different reactions depending on the reactive moiety. Well known as a redox substrate owing to the redox properties of the nicotinamide ring, β-NAD+ is also fundamental as a substrate of NAD+-consuming enzymes that cleave either high-energy bonds to catalyse their reactions. In this study, a panel of novel adenine-modified NAD+ derivatives was synthesized and biologically evaluated against different NAD+-consuming enzymes. The synthesis of NAD+ derivatives, modified in position 2, 6 or 8 of the adenine ring with aryl/heteroaryl groups, was accomplished by Suzuki-Miyaura cross-couplings. Their biological activity as inhibitors and/or non-natural substrates was assessed against a selected range of NAD+-consuming enzymes. The fluorescence of 8-aryl/heteroaryl NAD+ derivatives allowed their use as biochemical probes for the development of continuous biochemical assays to monitor NAD+-consuming enzyme activities. -

Living with a Cobalamin Cofactor Metabolism Defect Cbl Defects Are

Living with a cobalamin cofactor metabolism defect What you should know about cbl defects that cause homocystinuria The ABCs of cobalamin (cbl) defects Cobalamin cofactor metabolism defects = cbl defects Many different cbl defects cause homocystinuria. (And a few do not.) Each type is named with a letter of the alphabet. Not actual patients or caregivers Marcus has cblC defect Shayna has cblG defect A cbl defect can affect health in many ways Cbl defects impair the body’s ability to metabolize or break down an amino acid called homocysteine. The body makes homocysteine during the metabolism of methionine, another amino acid. Most foods contain methionine. Different forms of cobalamin, also known as vitamin B12, are also involved in the methionine metabolic process. If someone has a combined disorder, then both homocysteine and methylmalonic acid can build up in their blood. If someone has a single disorder, then only homocysteine may build up in their blood. In both types of disorders, serious health problems may develop. Symptoms of combined disorders The most common cbl defect is cblC defect. Like Marcus, most people with cblC defect begin to develop symptoms before they are a year old. This is the early-onset form of cblC defect. As a baby, Marcus was often fussy and didn’t want to eat. Among other symptoms that developed over time, Marcus’s parents began to notice that his eyes wandered. People with late-onset cblC defect may not develop symptoms until later in life – from childhood to adulthood. Late-onset symptoms may be milder than early- BRAIN & SPINAL CORD GROWTH & FEEDING onset symptoms. -

Pyruvate Dehydrogenase Complex Deficiency

Pavlu‑Pereira et al. Orphanet J Rare Dis (2020) 15:298 https://doi.org/10.1186/s13023‑020‑01586‑3 RESEARCH Open Access Pyruvate dehydrogenase complex defciency: updating the clinical, metabolic and mutational landscapes in a cohort of Portuguese patients Hana Pavlu‑Pereira1, Maria João Silva1,2, Cristina Florindo1, Sílvia Sequeira3, Ana Cristina Ferreira3, Sofa Duarte3, Ana Luísa Rodrigues4, Patrícia Janeiro4, Anabela Oliveira5, Daniel Gomes5, Anabela Bandeira6, Esmeralda Martins6, Roseli Gomes7, Sérgia Soares7, Isabel Tavares de Almeida1,2, João B. Vicente8* and Isabel Rivera1,2* Abstract Background: The pyruvate dehydrogenase complex (PDC) catalyzes the irreversible decarboxylation of pyruvate into acetyl‑CoA. PDC defciency can be caused by alterations in any of the genes encoding its several subunits. The resulting phenotype, though very heterogeneous, mainly afects the central nervous system. The aim of this study is to describe and discuss the clinical, biochemical and genotypic information from thirteen PDC defcient patients, thus seeking to establish possible genotype–phenotype correlations. Results: The mutational spectrum showed that seven patients carry mutations in the PDHA1 gene encoding the E1α subunit, fve patients carry mutations in the PDHX gene encoding the E3 binding protein, and the remaining patient carries mutations in the DLD gene encoding the E3 subunit. These data corroborate earlier reports describing PDHA1 mutations as the predominant cause of PDC defciency but also reveal a notable prevalence of PDHX mutations among Portuguese patients, most of them carrying what seems to be a private mutation (p.R284X). The biochemical analyses revealed high lactate and pyruvate plasma levels whereas the lactate/pyruvate ratio was below 16; enzy‑ matic activities, when compared to control values, indicated to be independent from the genotype and ranged from 8.5% to 30%, the latter being considered a cut‑of value for primary PDC defciency. -

Biomolecules-10-00573-V2.Pdf

biomolecules Article Calculation of the Geometries and Infrared Spectra of the Stacked Cofactor Flavin Adenine Dinucleotide (FAD) as the Prerequisite for Studies of Light-Triggered Proton and Electron Transfer Martina Kieninger 1,*, Oscar N. Ventura 1 and Tilman Kottke 2 1 CCBG, DETEMA, Facultad de Química, Isidoro de María 1616, 11800 Montevideo, Uruguay; [email protected] 2 Department of Chemistry, Physical and Biophysical Chemistry, Bielefeld University, Universitätsstr. 25, 33615 Bielefeld, Germany; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +598-2-2924-8396 Received: 23 December 2019; Accepted: 27 March 2020; Published: 9 April 2020 Abstract: Flavin cofactors, like flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD), are important electron shuttles in living systems. They catalyze a wide range of one- or two-electron redox reactions. Experimental investigations include UV-vis as well as infrared spectroscopy. FAD in aqueous solution exhibits a significantly shorter excited state lifetime than its analog, the flavin mononucleotide. This finding is explained by the presence of a “stacked” FAD conformation, in which isoalloxazine and adenine moieties form a π-complex. Stacking of the isoalloxazine and adenine rings should have an influence on the frequency of the vibrational modes. Density functional theory (DFT) studies of the closed form of FAD in microsolvation (explicit water) were used to reproduce the experimental infrared spectra, substantiating the prevalence of the stacked geometry of FAD in aqueous surroundings. It could be shown that the existence of the closed structure in FAD can be narrowed down to the presence of only a single water molecule between the third hydroxyl group (of the ribityl chain) and the N7 in the adenine ring of FAD. -

How Do Bacterial Cells Ensure That Metalloproteins Get the Correct Metal?

REVIEWS How do bacterial cells ensure that metalloproteins get the correct metal? Kevin J. Waldron and Nigel J. Robinson Abstract | Protein metal-coordination sites are richly varied and exquisitely attuned to their inorganic partners, yet many metalloproteins still select the wrong metals when presented with mixtures of elements. Cells have evolved elaborate mechanisms to scavenge for sufficient metal atoms to meet their needs and to adjust their needs to match supply. Metal sensors, transporters and stores have often been discovered as metal-resistance determinants, but it is emerging that they perform a broader role in microbial physiology: they allow cells to overcome inadequate protein metal affinities to populate large numbers of metalloproteins with the right metals. It has been estimated that one-quarter to one-third of all Both monovalent (cuprous) copper, which is expected proteins require metals, although the exploitation of ele- to predominate in a reducing cytosol, and trivalent ments varies from cell to cell and has probably altered over (ferric) iron, which is expected to predominate in an the aeons to match geochemistry1–3 (BOX 1). The propor- oxidizing periplasm, are also highly competitive, as are tions have been inferred from the numbers of homologues several non-essential metals, such as cadmium, mercury of known metalloproteins, and other deduced metal- and silver6 (BOX 2). How can a cell simultaneously contain binding motifs, encoded within sequenced genomes. A some proteins that require copper or zinc and others that large experimental estimate was generated using native require uncompetitive metals, such as magnesium or polyacrylamide-gel electrophoresis of extracts from iron- manganese? In a most simplistic model in which pro- rich Ferroplasma acidiphilum followed by the detection of teins pick elements from a cytosol in which all divalent metal in protein spots using inductively coupled plasma metals are present and abundant, all proteins would bind mass spectrometry4. -

University of Groningen Exploring the Cofactor-Binding and Biocatalytic

University of Groningen Exploring the cofactor-binding and biocatalytic properties of flavin-containing enzymes Kopacz, Malgorzata IMPORTANT NOTE: You are advised to consult the publisher's version (publisher's PDF) if you wish to cite from it. Please check the document version below. Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Publication date: 2014 Link to publication in University of Groningen/UMCG research database Citation for published version (APA): Kopacz, M. (2014). Exploring the cofactor-binding and biocatalytic properties of flavin-containing enzymes. Copyright Other than for strictly personal use, it is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). The publication may also be distributed here under the terms of Article 25fa of the Dutch Copyright Act, indicated by the “Taverne” license. More information can be found on the University of Groningen website: https://www.rug.nl/library/open-access/self-archiving-pure/taverne- amendment. Take-down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Downloaded from the University of Groningen/UMCG research database (Pure): http://www.rug.nl/research/portal. For technical reasons the number of authors shown on this cover page is limited to 10 maximum. Download date: 29-09-2021 Exploring the cofactor-binding and biocatalytic properties of flavin-containing enzymes Małgorzata M. Kopacz The research described in this thesis was carried out in the research group Molecular Enzymology of the Groningen Biomolecular Sciences and Biotechnology Institute (GBB), according to the requirements of the Graduate School of Science, Faculty of Mathematics and Natural Sciences. -

Structural Insight Into Signal Conversion and Inactivation by Ntpdase2 in Purinergic Signaling

Structural insight into signal conversion and inactivation by NTPDase2 in purinergic signaling Matthias Zebisch and Norbert Stra¨ ter* Center for Biotechnology and Biomedicine, Institute of Bioanalytical Chemistry, Faculty of Chemistry and Mineralogy, University of Leipzig, Deutscher Platz 5, 04103 Leipzig, Germany Communicated by William N. Lipscomb, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, March 13, 2008 (received for review January 4, 2008) Cell surface-located nucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolases prominent DXG motif and correspond to the - and ␥-phos- (NTPDase1, -2, -3, and -8) are oligomeric integral membrane pro- phate binding loops of soluble members of the actin/hsp70/sugar teins responsible for signal conversion and inactivation in extra- kinase superfamily (17). cellular nucleotide-mediated ‘‘purinergic’’ signaling. They catalyze NTPDases differ significantly in product formation. This is of the sequential hydrolysis of the signaling molecule ATP via ADP to considerable relevance for the regulation of nucleotide signaling. AMP. Here we present the structure of the extracellular domain of NTPDase1, which corresponds to the lymphoid cell activation Rattus norvegicus NTPDase2 in an active state at resolutions antigen CD39, hydrolyzes ATP processively to AMP [i.e., without between 1.7 Å and 2.1 Å in four different forms: (i) apo form, (ii) release of the intermediate ADP from the active site (18, 19)]. The ternary complex with the nonhydrolyzable ATP analog AMPPNP ectoenzyme is expressed by cells of the immune system, quiescent and cofactor Ca2؉,(iii) quaternary complex with Ca2؉ and bound endothelial cells, vascular smooth muscle cells, and others. Because products AMP and phosphate, and (iv) binary product complex of its ability to hydrolyze both ATP and the platelet activator ADP with AMP only. -

Assessing the Thiamine Diphosphate Dependent Pyruvate Dehydrogenase E1 Subunit for Carboligation Reactions with Aliphatic Ketoacids

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Article Assessing the Thiamine Diphosphate Dependent Pyruvate Dehydrogenase E1 Subunit for Carboligation Reactions with Aliphatic Ketoacids Stefan R. Marsden, Duncan G. G. McMillan and Ulf Hanefeld * Biokatalyse, Afdeling Biotechnologie, Technische Universiteit Delft, Van der Maasweg 9, 2629HZ Delft, The Netherlands; [email protected] (S.R.M.); [email protected] (D.G.G.M.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 12 October 2020; Accepted: 12 November 2020; Published: 16 November 2020 Abstract: The synthetic properties of the Thiamine diphosphate (ThDP)-dependent pyruvate dehydrogenase E1 subunit from Escherichia coli (EcPDH E1) was assessed for carboligation reactions with aliphatic ketoacids. Due to its role in metabolism, EcPDH E1 was previously characterised with respect to its biochemical properties, but it was never applied for synthetic purposes. Here, we show that EcPDH E1 is a promising biocatalyst for the production of chiral α-hydroxyketones. WT EcPDH E1 shows a 180–250-fold higher catalytic efficiency towards 2-oxobutyrate or pyruvate, respectively, in comparison to engineered transketolase variants from Geobacillus stearothermophilus (TKGST). Its broad active site cleft allows for the efficient conversion of both (R)- and (S)-configured α-hydroxyaldehydes, next to linear and branched aliphatic aldehydes as acceptor substrates under kinetically controlled conditions. The alternate, thermodynamically controlled self-reaction of aliphatic aldehydes was shown to be limited to low levels of conversion, which we propose to be due to their large hydration constants. Additionally, the thermodynamically controlled approach was demonstrated to suffer from a loss of stereoselectivity, which makes it unfeasible for aliphatic substrates. Keywords: Thiamine diphosphate; transketolase; C-C bond formation; kinetic control; acyloins 1. -

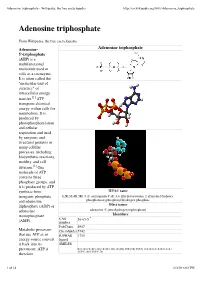

Adenosine Triphosphate - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Adenosine triphosphate - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Adenosine_triphosphate Adenosine triphosphate From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Adenosine- Adenosine triphosphate 5'-triphosphate (ATP) is a multifunctional nucleotide used in cells as a coenzyme. It is often called the "molecular unit of currency" of intracellular energy transfer.[1] ATP transports chemical energy within cells for metabolism. It is produced by photophosphorylation and cellular respiration and used by enzymes and structural proteins in many cellular processes, including biosynthetic reactions, motility, and cell division.[2] One molecule of ATP contains three phosphate groups, and it is produced by ATP synthase from IUPAC name inorganic phosphate [(2R,3S,4R,5R)-5-(6-aminopurin-9-yl)-3,4-dihydroxyoxolan-2-yl]methyl(hydroxy- and adenosine phosphonooxyphosphoryl)hydrogen phosphate diphosphate (ADP) or Other names adenosine adenosine 5'-(tetrahydrogen triphosphate) monophosphate Identifiers CAS 56-65-5 (AMP). number PubChem 5957 Metabolic processes ChemSpider 5742 that use ATP as an IUPHAR 1713 energy source convert ligand it back into its SMILES precursors. ATP is O=P(O)(O)OP(=O)(O)OP(=O)(O)OC[C@H]3O[C@@H](n2cnc1c(ncnc12)N) [C@H](O)[C@@H]3O therefore 1 of 14 6/3/10 6:02 PM Adenosine triphosphate - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Adenosine_triphosphate continuously recycled InChI in organisms: the 1/C10H16N5O13P3 human body, which /c11-8-5-9(13-2-12-8)15(3-14-5)10-7(17)6(16)4(26-10)1-25-30(21,22)28-31(23,24)27-29(18,19)20