Dr. Hepcat” Durst and the Desegregation of Radio in Central Texas, 1948-1963

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mar.-Apr.2020 Highlites

Prospect Senior Center 6 Center Street Prospect, CT 06712 (203)758-5300 (203)758-3837 Fax Lucy Smegielski Mar.-Apr.2020 Director - Editor Municipal Agent Highlites Town of Prospect STAFF Lorraine Lori Susan Lirene Melody Matt Maglaris Anderson DaSilva Lorensen Heitz Kalitta From the Director… Dear Members… I believe in being upfront and addressing things head-on. Therefore, I am using this plat- form to address some issues that have come to my attention. Since the cost for out-of-town memberships to our Senior Center went up in January 2020, there have been a few miscon- ceptions that have come to my attention. First and foremost, the one rumor that I would definitely like to address is the story going around that the Prospect Town Council raised the dues of our out-of-town members because they are trying to “get rid” of the non-residents that come here. The story goes that the Town Council is trying to keep our Senior Center strictly for Prospect residents only. Nothing could be further from the truth. I value the out-of-town members who come here. I feel they have contributed significantly to the growth of our Senior Center. Many of these members run programs here and volun- teer in a number of different capacities. They are my lifeline and help me in ways that I could never repay them for. I and the Town Council members would never want to “get rid” of them. I will tell you point blank why the Town Council decided to raise membership dues for out- of-town members. -

Waylon Jennings

TABLE OF CONTENTS 3 Introduction 4 About the Guide 5 Pre and Post-Lesson: Anticipation Guide 6 Lesson 1: Introduction to Outlaws 7 Lesson 1: Worksheet 8 Lyric Sheet: Me and Paul 9 Lesson 2: Who Were The Outlaws? 10 Lesson 3: Outlaw Influence 11 Lesson 3: Worksheet 12 Activities: Jigsaw Texts 14 Lyric Sheet: Are You Sure Hank Done It This Way 15 Lesson 4: T for Texas, T for Tennessee 16 Lesson 4: Worksheet 17 Lesson 5: Literary Lyrics 19 “London” by William Blake 20 Complete Tennessee Standards 22 Complete Texas Standards 23 Biographies 3-6 Table of Contents 2 Outlaws and Armadillos: Country’s Roaring ‘70s examines how the Outlaw movement greatly enlarged country music’s audience during the 1970s. Led by pacesetters such as Willie Nelson, Waylon Jennings, Kris Kristofferson, and Bobby Bare, artists in Nashville and Austin demanded the creative freedom to make their own country music, different from the pop-oriented sound that prevailed at the time. This exhibition also examines the cultures of Nashville and fiercely independent Austin, and the complicated, surprising relationships between the two. Artwork by Sam Yeates, Rising from the Ashes, Willie Takes Flight for Austin (2017) 3-6 Introduction 3 This interdisciplinary lesson guide allows classrooms to explore the exhibition Outlaws and Armadillos: Country’s Roaring ‘70s on view at the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum® from May 25, 2018 – February 14, 2021. Students will examine the causes and effects of the Outlaw movement through analysis of art, music, video, and nonfiction texts. In doing so, students will gain an understanding of the culture of this movement; who and what influenced it; and how these changes diversified country music’s audience during this time. -

My Guitar Is a Camera

My Guitar Is a Camera John and Robin Dickson Series in Texas Music Sponsored by the Center for Texas Music History Texas State University–San Marcos Gary Hartman, General Editor Casey_pages.indd 1 7/10/17 10:23 AM Contents Foreword ix Steve Miller Acknowledgments xi Introduction xiii Tom Reynolds From Hendrix to Now: Watt, His Camera, and His Odyssey xv Herman Bennett, with Watt M. Casey Jr. 1. Witnesses: The Music, the Wizard, and Me 1 Mark Seal 2. At Home and on the Road: 1970–1975 11 3. Got Them Texas Blues: Early Days at Antone’s 31 4. Rolling Thunder: Dylan, Guitar Gods, and Joni 54 5. Willie, Sir Douglas, and the Austin Music Creation Myth 60 Joe Nick Patoski 6. Cosmic Cowboys and Heavenly Hippies: The Armadillo and Elsewhere 68 7. The Boss in Texas and the USA 96 8. And What Has Happened Since 104 Photographer and Contributors 123 Index 125 Casey_pages.indd 7 7/10/17 10:23 AM Casey_pages.indd 10 7/10/17 10:23 AM Jimi Hendrix poster. Courtesy Paul Gongaware and Concerts West. Casey_pages.indd 14 7/10/17 10:24 AM From Hendrix to Now Watt, His Camera, and His Odyssey HERMAN BENNETT, WITH WATT M. CASEY JR. Watt Casey’s journey as a photographer can be In the summer of 1970, Watt arrived in Aus- traced back to an event on May 10, 1970, at San tin with the intention of getting a degree from Antonio’s Hemisphere Arena: the Cry of Love the University of Texas. Having heard about a Tour. -

African American Resource Guide

AFRICAN AMERICAN RESOURCE GUIDE Sources of Information Relating to African Americans in Austin and Travis County Austin History Center Austin Public Library Originally Archived by Karen Riles Austin History Center Neighborhood Liaison 2016-2018 Archived by: LaToya Devezin, C.A. African American Community Archivist 2018-2020 Archived by: kYmberly Keeton, M.L.S., C.A., 2018-2020 African American Community Archivist & Librarian Shukri Shukri Bana, Graduate Student Fellow Masters in Women and Gender Studies at UT Austin Ashley Charles, Undergraduate Student Fellow Black Studies Department, University of Texas at Austin The purpose of the Austin History Center is to provide customers with information about the history and current events of Austin and Travis County by collecting, organizing, and preserving research materials and assisting in their use. INTRODUCTION The collections of the Austin History Center contain valuable materials about Austin’s African American communities, although there is much that remains to be documented. The materials in this bibliography are arranged by collection unit of the Austin History Center. Within each collection unit, items are arranged in shelf-list order. This bibliography is one in a series of updates of the original 1979 bibliography. It reflects the addition of materials to the Austin History Center based on the recommendations and donations of many generous individuals and support groups. The Austin History Center card catalog supplements the online computer catalog by providing analytical entries to information in periodicals and other materials in addition to listing collection holdings by author, title, and subject. These entries, although indexing ended in the 1990s, lead to specific articles and other information in sources that would otherwise be time-consuming to find and could be easily overlooked. -

Arts and Entertainment Guide (Pdf) Download

ART MUSIC CULTURE Greater Austin & ENTERTAINMENTARTS Independence Title Explore www.IndependenceTitle.com “I didn't come here and I ain't leavin'. ” -Willie Nelson Austin’s artistic side is alive and well. including Austin Lyric Opera, Ballet institution serving up musical theater We are a creative community of Austin, and the Austin Symphony, as under the stars, celebrated its 50th designers, painters, sculptors, dancers, well as a rich local tradition of innovative anniversary in 2008. The Texas Film filmmakers, musicians . artists of all and avant-guarde theater groups. Commission is headquartered in Austin, kinds. And Austin is as much our and increasingly the city is being identity as it is our home. Austin is a creative community with a utilized as a favorite film location. The burgeoning circle of live performance city hosts several film festivals, The venues for experiencing art in theater venues, including the Long including the famed SXSW Film Festival Austin are very diverse. The nation's Center for the Performing Arts, held every Spring. Get out and about largest university-owned collection is Paramount Theatre, Zachary Scott and explore! exhibited at the Blanton Museum, and Theatre Center, Vortex Repertory you can view up-and-coming talent in Company, Salvage Vanguard Theater, our more intimate gallery settings. Scottish Rite Children's Theater, Hyde Austin boasts several world-renowned Park Theatre, and Esther's Follies. The classical performing arts organizations, Zilker Summer Musical, an Austin Performing Arts Choir A -

Off the Beaten Path EXPLORING HAMILTON POOL’S WATERFALL and GEOLOGICAL WONDERS

Iid Guide AUSTIN2015/2016 Off the Beaten Path EXPLORING HAMILTON POOL’S WATERFALL AND GEOLOGICAL WONDERS TUNE IN: ESSENTIAL YOUR GUIDE TO AUSTIN’S NEARBY GEMS: PERFECT MUSIC EXPERIENCES NEIGHBORHOODS HILL COUNTRY ROAD TRIPS PAGE 10 PAGE 15 PAGE 45 WE DITCHED THE LANDSCAPES FOR MORE SOUNDSCAPES. If you’re going to spend some time in Austin, shouldn’t you stay in a suite that feels like it’s actually in Austin? EXPLORE OUR REINVENTION at Radisson.com/AustinTX AUSTIN CONVENTION & VISITORS BUREAU 111 Congress Ave., Suite 700, Austin, TX 78701 800-926-2282, Fax: 512-583-7282, www.austintexas.org President & CEO Robert M. Lander Vice President & Chief Marketing Officer Julie Chase Director of Marketing Communications Jennifer Walker Director of Digital Marketing Katie Cook Director of Content & Publishing Susan Richardson Director of Austin Film Commission Brian Gannon Senior Communications Manager Shilpa Bakre Tourism & PR Manager Lourdes Gomez Film, Music & Marketing Coordinator Kristen Maurel Marketing & Tourism Coordinator Rebekah Grmela AUSTIN VISITOR CENTER 602 E. Fourth St., Austin, TX 78701 866-GO-AUSTIN, 512-478-0098 Hours: Mon. – Sat. 9 a.m. – 5 p.m., Sun. 10 a.m.– 5 p.m. Director of Retail and Visitor Services Cheri Winterrowd Visitor Center Staff Erin Bevins, Harrison Eppright, Tracy Flynn, Patsy Stephenson, Spencer Streetman, Cynthia Trenckmann PUBLISHED BY MILES www.milespartnership.com Sales Office: P.O. Box 42253, Austin, TX 78704 512-432-5470, Fax: 512-857-0137 National Sales: 303-867-8236 Corporate Office: 800-303-9328 PUBLICATION TEAM Account Director Rachael Root Publication Editor Lisa Blake Art Director Kelly Ruhland Ad & Data Manager Hanna Berglund Account Executives Daja Gegen, Susan Richardson Contributing Writers Amy Gabriel, Laura Mier, Kelly Stocker SUPPORT AND LEADERSHIP Chief Executive Officer/President Roger Miles Chief Financial Officer Dianne Gates Chief Operating Officer David Burgess For advertising inquiries, please contact Daja Gegen at [email protected]. -

The Dicks Top: the Dicks in the Early 1980S

The Dicks Top: The Dicks in the early 1980s. Photo: Mark Christal. Bottom: The Dicks in 2005. L to R: Buxf Parrot (bass), Gary Floyd (vocals), Pat Deason (drums). Photo: Carlos Lowry. 4 The Dicks The Dicks were confrontational right out of the gate. A seminal band, and not just because singer Gary Floyd sometimes threw condoms filled with fake cum into the crowd. By all accounts, the Dicks challenged their audiences and revealed new possibilities. They made their concerts a hell of an experience and created memorable political music with a sound that was completely their own. The Dicks formed in Austin in 1980. They relocated to San Francisco and changed personnel halfway through the duration of the group, before breaking up in 1986. When one thinks of early hardcore punk music in Texas, a small but critical list of bands comes to mind immediately: the Big Boys, Dirty Rotten Imbeciles (DRI), Butthole Surfers, Really Red, the Stains (later renamed MDC), the Offenders and the Dicks. The Dicks first came to the ears of many with a three song 7”, The Dicks Hate the Police . The band re - leased this 7” in 1980 on their own Radical Records label (by the way, no relation to the more well known R Radical label that Dave Dictor from Stains and MDC created soon after). The song “The Dicks Hate the Police” is an exceptionally memorable and passionate first statement for a band. These lyrics by guitarist Glen Taylor remain stinging and painful, especially while being delivered in a voice that is both mournful and pissed off at the same time: Daddy, Daddy, Daddy Proud of his son He’s got a good job Kills niggers and Mexicans We’ll tell you something and it’s true If you can’t find justice it’ll find you The popular Seattle-based band Mudhoney covered the song as “Hate the Police.” This brought the Dicks’ music to the attention of many thousands of people that might not have heard them otherwise. -

Raoul Hernandez

Raoul Hernandez PROFESSIONAL GOAL Clinical professorship at the university level. EDUCATION Stanford University, Stanford, Calif., M.A., Communication, 1992 Pomona College, Claremont, Calif., B.A., English 1987 EXPERTISE / PROPOSED CLASSES Editing Music Journalism Reporting Art of the Review Music Interview Technique Film Editing in Real Time Public Speaking Jazz History LANGUAGES Spanish (bilingual) PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE Music Editor/Senior Editor The Austin Chronicle, 1994-present Assistant Music Editor The Austin Chronicle, 1993-1994 2603 Roxmoor Dr. Editorial Assistant Austin, Texas, 78723 The San Francisco Examiner, 1991-1992 News Assistant (512) 914-4441 National Broadcasting Company: KNBR-68, San Francisco, 1987-1988 [email protected] Delivery Adolescent @ChroniclyRaoul The Contra Costa Times, Walnut Creek, Calif., 1975-1980 BOOKS EDITOR Bentley, Bill, Smithsonian Rock & Roll: Live & Unseen, Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Books, 2017 CONTRIBUTOR The Jesus Lizard & David Yow, The Jesus Lizard Book, New York: Akashic Books, 2014 Powell, Austin & Doug Freeman, The Austin Chronicle Music Anthology, Austin: The University of Texas Press, 2011 Peveto, Geoff & Paula Scher, Rock Paper Show: Flatstock Volume One, New York: Soundscreen Design, 2011 PERIODICALS (select) PUBLICATIONS “The Austin Music Awards’ Ecstatic “John Carpenter, Rock Star,” Experience, The Austin Chronicle, The Austin Chronicle, 15 June 2016 1 March 2018 “Charles Attal Discusses C3/Live Nation “Where Does Margo Price Get Off?” Deal,” The Austin Chronicle, 26 -

Texas Music Conference, Dallas Public Library Additional On-Line

Texas Music Conference, Dallas Public Library Additional On‐Line Information As Big as All of Texas: Overview of Music in the Lone Star State (Kevin Mooney) Presenter biography: http://www.music.txstate.edu/facultystaff/bios/mooney.html Subject information: http://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/TT/xbt2.html http://ecommons.txstate.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1006&context=jtmh http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Texas_music http://www.txstate.edu/ctmh Big D Meets the Big Easy—And All That (Texas) Jazz (Tim Schuller) Subject information: http://openlibrary.org/b/OL8165270M/MusicHound‐Blues http://www.centexjazz.com http://www1.onr.com/atjs http://www.tjea.org http://www.texasjazz‐fest.org Dancing about History: The Continuing Saga of the Fort Griffin Fandangle (Jim Coker) Presenter biography: http://dallaslibrary.org/fineArts/docs/coker.pdf Subject information: http://www.fortgriffinfandangle.org http://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/FF/kkf2.html http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fort_Griffin_Fandangle From the Delta to Deep Ellum: Texas Blues (Jay Brakefield, Michael Dyson, Alan Govenar) Presenter biography: http://www.docarts.com http://www.blueshoeproject.org http://www.theeagle.com http://dallaslibrary.org/fineArts/docs/govenar.pdf Subject information: http://texasbluesassociation.com http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Texas_blues http://www.texasbluesradio.com http://dentonblues.com King of Western Swing: The Life and Legacy of Bob Wills (Jeffrey W. Storie) Presenter biography: http://webtest.dbu.edu/fine_arts/Faculty/MusicFaculty‐JeffreyStorie.asp -

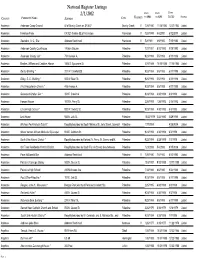

National Register Listings 2/1/2012 DATE DATE DATE to SBR to NPS LISTED STATUS COUNTY PROPERTY NAME ADDRESS CITY VICINITY

National Register Listings 2/1/2012 DATE DATE DATE TO SBR TO NPS LISTED STATUS COUNTY PROPERTY NAME ADDRESS CITY VICINITY AndersonAnderson Camp Ground W of Brushy Creek on SR 837 Brushy Creek V7/25/1980 11/18/1982 12/27/1982 Listed AndersonFreeman Farm CR 323 3 miles SE of Frankston Frankston V7/24/1999 5/4/2000 6/12/2000 Listed AndersonSaunders, A. C., Site Address Restricted Frankston V5/2/1981 6/9/1982 7/15/1982 Listed AndersonAnderson County Courthouse 1 Public Square Palestine7/27/1991 8/12/1992 9/28/1992 Listed AndersonAnderson County Jail * 704 Avenue A. Palestine9/23/1994 5/5/1998 6/11/1998 Listed AndersonBroyles, William and Caroline, House 1305 S. Sycamore St. Palestine5/21/1988 10/10/1988 11/10/1988 Listed AndersonDenby Building * 201 W. Crawford St. Palestine9/23/1994 5/5/1998 6/11/1998 Listed AndersonDilley, G. E., Building * 503 W. Main St. Palestine9/23/1994 5/5/1998 6/11/1998 Listed AndersonFirst Presbyterian Church * 406 Avenue A Palestine9/23/1994 5/5/1998 6/11/1998 Listed AndersonGatewood-Shelton Gin * 304 E. Crawford Palestine9/23/1994 4/30/1998 6/3/1998 Listed AndersonHoward House 1011 N. Perry St. Palestine3/28/1992 1/26/1993 3/14/1993 Listed AndersonLincoln High School * 920 W. Swantz St. Palestine9/23/1994 4/30/1998 6/3/1998 Listed AndersonLink House 925 N. Link St. Palestine10/23/1979 3/24/1980 5/29/1980 Listed AndersonMichaux Park Historic District * Roughly bounded by South Michaux St., Jolly Street, Crockett Palestine1/17/2004 4/28/2004 Listed AndersonMount Vernon African Methodist Episcopal 913 E. -

Mosser/Musser Family

MOSSER/MUSSER FAMILY WW by ANITA L. MOTT HERITAGE BOOKS, INC. M& FAMILY HISTORY LIBRARY 35 NORTH WEST TEMPLE SALT LAKE CITY, UTAH 84150 . Copyright 1999 Anita L. Mott Published 1999 by HERITAGE BOOKS, INC. 1540E Pointer Ridge Place Bowie, Maryland 20716 1-800-398-7709 http://www.heritagebooks.com ISBN: 0-7884-1187-X A Complete Catalog Listing Hundreds of Titles On History, Genealogy, and Americana Available Free Upon Request ^ ^ Q* Mosser/Musser Family Anita L. Mott. A genealogical survey of the Mosser family in America from colonial time to the present day. This enlightening text helps to dispel much of the confusion surrounding the history of the family in North America, specifically the wide variation in spellings of the name as the family spread across the country. A traditional German surname, the original Mosser was often misinterpreted in public records due to peculiarities in handwriting and the language barrier between the German immigrants and the various ship's stewards, custom house officials and later census takers whose records form the bulk of the early data on the family. In some cases, members of immediate families would each be registered under a different surname creating a tangled web of Mossers, Mosers, Mussers, Musers, Messers, Mosiers, Moyers and even a few Masons for today's genealogists to contend with. The text begins with a brief history of the family and the establishment of the "Pennsylvania Dutch" community. Individual chapters are devoted to the lines of descent from Hans Martin Mosser, Hans Adam Mosser, Hans Paulus Mosser and Philip Moser. Further chapters are included on Mosers not yet placed within known lines of descent and an exploration of twelve collateral lines for the allied families Boehm, Everett, Hower, Koppenhoffer, Lichtenwallner, Long, Oswald, Seberling and Wannamaker. -

Talk to Me: the History of San Antonio's West Side Sound

“Talk to Me” The History of San Antonio’s West Side Sound1 Alex La Rotta 8 The Twisters (background) playing behind the Royal Jesters, ca 1958. Courtesy Ramn Hernández. Contrary to its name, the “West Side Sound” did not actually originate on the West Side of San Antonio. Nor, for that matter, is it a singular “sound” that can be easily defined or categorized. In fact, the term “West Side Sound” was not widely used until San Antonio musician Doug Sahm applied it to his band, the West Side Horns, on his 1983 album, The West Side Sound Rolls Again. Since then, journalists, music fans, and even Sahm himself 9 have retrofitted the term to describe a particular style that emerged from San Antonio and the greater South Texas region beginning in the 1950s and continuing into the early twenty-first century.2 So what, then, is the West Side Sound? To quote historian Allen Olsen, the West Side Sound is “a remarkable amalgamation of different ethnic musical influences found in and around San Antonio and South-Central Texas. It includes blues, conjunto, country, rhythm and blues, polka, swamp pop, rock and roll, and other seemingly disparate styles.”3 To others, the West Side Sound is more of a feeling than a specific musical genre. In the words of Texas Tornados drummer Ernie Durawa, “It’s just that San Antonio thing…nowhere else in the world has it.”4 Both descriptions of the West Side Sound are accurate, but they really only tell part of the story of this remarkable musical hybrid.