The Education Industry: 2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Language and Communication Skills Training for the 21St Century 1

WORK. STUDY. LIVE. Language and Communication Skills Training for the 21st Century 1 Leading the world in language and communication skills training for 21st Century global citizens. We give 21st Century global citizens the communication skills and confidence to reach their full potential in life. In this increasingly connected, competitive world, everybody’s life path is unique. From your studies to your career and beyond, we can help you to not only break down language barriers, but to truly communicate, collaborate and succeed in whatever you choose to do. Our smart learning system and supportive team ensure you get desired outcomes, fast. It’s time to take your place on the international stage. Welcome to Eurocentres! EUROCENTRES WELCOME TO 1 Welcome to Eurocentres 3 Setting Standards in 21st Century Communication 5 The Eurocentres Methodology 7 Your Learning Journey 9 Outside the Classroom 11 Courses 19 Our Schools 21 Destination Finder CONTENTS 2 3 Countries in which CEFR Study abroad locations informs language policy and is used as a benchmar- Study at home locations king tool for major exams (IELTS, TOEIC, TOEFL). We set the standards other schools strive to meet. Choose Eurocentres and learn from the experts behind the most widely used communication benchmark in the world — the CEFR. Updated for the CEFR 21st Century As a unique consultant A major recent update to the Council of Europe to the CEFR adds the for language teaching communication goals and learning, Eurocentres that are central to 21st is known as the leading Century Skills — the vital developer of the Common ‘soft’ skills that are now European Framework of CENTURY widely recognised as Reference for Languages essential to work, study (CEFR). -

Great Britain and Ireland

Great Britain and Ireland London Central London Eltham Cambridge One of the largest and most cosmopolitan The school is located in the grounds of a royal As one of the most historic and popular cities in the world, London sets trends in palace in a leafy suburb called Eltham, close student cities in Europe, Cambridge is a fashion, music, design and film. Our school to Greenwich, where the world’s time is set. convenient size for getting around either on is based in Victoria with access to a private Enjoy the advantages of a quieter suburban foot or by bike. Young people from all over garden. A huge variety of bars, restaurants, location with access to city life only a the world enjoy student life and the numerous theatres and concerts means you will always 25 minute train ride from central London. opportunities to play sport, go to the theatre, have plenty of things to do. cinema, pubs and go shopping. Lidia Zhou, Italy Yuki Nakamoto, Japan Fan Vu, Ukraine The teachers are extraordinary, The main reason why I chose The teachers are very kind and because they teach with passion, Eurocentres London Eltham is have good knowledge to teach so I was more motivated to that the location of school is and the area is lovely with learn and improve my English. suitable for study, calm and lots of facilities for students. It’s the best school for me still close to the centre of I really suggest this school to to learn English because of its personalised London. -

Financial Technology Sector Summary

Financial Technology Sector Summary July 30, 2014 Financial Technology Sector Summary Table of Contents I. GCA Savvian Overview II. Market Summary III. Payments / Banking IV. Securities / Capital Markets / Data & Analytics V. Healthcare / Insurance I. GCA Savvian Overview GCA Savvian Overview Highlights Firm Statistics GCA Savvian Focus . Over 225 professionals today Mergers & Acquisitions Private Capital Markets . Full spectrum of buy-side, sell- . Agented private capital raiser . Headquarters in San Francisco and Tokyo; offices in New side and strategic advisory York, London, Shanghai, Mumbai, and Osaka . Equity and debt capital markets . Public and private company advisory services experience . Provides mergers and acquisitions advisory services, private . Core competency, with important capital & capital markets advisory services, and principal . Strategic early-stage growth relationships among the venture investing companies through industry capital and private equity defining, multi-billion dollar community transactions . Over 500 transactions completed . Publicly traded on the Tokyo Stock Exchange (2174) Senior level attention and focus, Relationships and market extensive transaction intelligence; a highly experienced team in experience and deep domain insight the industry Global Advisory Firm Market Positioning Bulge Bracket Growth Sector Focus Transaction Expertise . Senior Team with . Growth Company Focus Unparalleled Transaction . Sector Expertise / Domain Experience Knowledge . Highest Quality Client . Private Capital Access -

Eurocentres, Eltham

Language Learning Worldwide 2017 English, French, Spanish, Italian, German, Japanese, Russian. eurocentres.com Book at worldwide lowest price at: https://www.languagecourse.net/school-eurocentres-eltham.php3 +1 646 503 18 10 +44 330 124 03 17 +34 93 220 38 75 +33 1-78416974 +41 225 180 700 +49 221 162 56897 +43 720116182 +31 858880253 +7 4995000466 +46 844 68 36 76 +47 219 30 570 +45 898 83 996 +39 02-94751194 +48 223 988 072 +81 345 895 399 +55 213 958 08 76 +86 19816218990 The world of Eurocentres CANADA Vancouver Toronto Lunenburg East Lansing Boston USA New York Santa Barbara EUROPE Los Angeles San Diego Galway Miami Cambridge Berlin MEXICO Playa del Carmen Dublin London Brighton Bournemouth Paris La Rochelle Amboise Lausanne Florence PERU Madrid Barcelona Cuzco Valencia Malta Eurocentres schools Partner schools Book at worldwide lowest price at: https://www.languagecourse.net/school-eurocentres-eltham.php3 +1 646 503 18 10 +44 330 124 03 17 +34 93 220 38 75 +33 1-78416974 +41 225 180 700 +49 221 162 56897 +43 720116182 +31 858880253 +7 4995000466 +46 844 68 36 76 +47 219 30 570 +45 898 83 996 +39 02-94751194 +48 223 988 072 +81 345 895 399 +55 213 958 08 76 +86 19816218990 RUSSIA St. Petersburg Moscow Kanazawa JAPAN Cairns AUSTRALIA Brisbane Gold Coast SOUTH AFRIca Perth Sydney Cape Town Melbourne Auckland NEW ZEALAND Book at worldwide lowest price at: https://www.languagecourse.net/school-eurocentres-eltham.php3 +1 646 503 18 10 +44 330 124 03 17 +34 93 220 38 75 +33 1-78416974 +41 225 180 700 +49 221 162 56897 +43 720116182 +31 -

ANNUAL REPORT 2012 Contents | Letter to Shareholders Page 1 | Form 10-K Page 5 | to Our Fellow Shareholders

ANNUAL REPORT 2012 Contents | Letter to Shareholders page 1 | Form 10-K page 5 | To Our Fellow Shareholders Fiscal year 2012 marks the beginning of a period of strategic expansion for Apollo Investment Corporation (the “Company”). As a result of the global financial crisis and increased regulation of banks and other capital providers, we believe there are sizable voids in today’s lending landscape. By increasing our focus on areas where others are not, we believe that we will be able to play a crucial role of “solution provider” for businesses in need of capital. While our core strategy remains focused on providing financing solutions to middle Issuance of Asset Backed Securities* $1,400 market companies, we intend to broaden our $1,233 investment footprint to offer a more diverse array of $1,200 $1,000 -87% private market debt solutions. More specifically, we $769 $800 plan to reduce our exposure to subordinated debt $ in billions $600 and increase our exposure to proprietary middle $400 $219 $184 market originated senior secured debt as well as $200 $127 $158 $0 other areas of specialized lending where financing 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 voids are more pronounced. * Source: Bloomberg We have begun to reposition our portfolio into investment strategies that fill some of the voids in today’s market place, leverage the Company’s strengths, take advantage of our permanent capital and offer what we believe are attractive risk adjusted returns. To that end, in April 2012, we made an equity investment in a senior loan vehicle managed by an affiliate of Madison Capital Funding, a leading middle market senior lender. -

Directory National Association of Therapeutic Schools and Programs

NATSAP 2009 Directory National Association of Therapeutic Schools and Programs NATSAP 2009 DIRECTORY e only bee, th s th at e i m op ak H es “ h o n e y w i t h o u t f l o w e r s , ” - R o b e r t G r e e n I n g e r s o l l Schools and Programs for Young People Experiencing Behavioral, Psychiatric and Learning Diffi culties NATSAP • www.natsap.org • (301) 986-8770 1 NATSAP 2009 Directory NATSAP 2009 Directory TABLE OF CONTENTS Page About NATSAP ............................................................................................3 NATSAP Ethical Principles ..........................................................................4 Program Definitions ......................................................................................5-6 NATSAP Alumni Advisory Council ............................................................10 Questions to Ask Before Making a Final Placement ....................................11-14 Program Listing By Name ............................................................................11-14 Program Directory Listings ...........................................................................16-187 Program Listing By State ...............................................................................................188-192 By Gender ...........................................................................................193-195 By Age ................................................................................................195-199 By Program Type ................................................................................200-202 -

Therapeutic Boarding Schools, Wilderness Camps, Boot Camps and Behavior Modification Facilities, Have Sprung up in Greater Numbers Since the 1990S

CHILD ABUSE AND DECEPTIVE MARKETING BY RESIDENTIAL PROGRAMS FOR TEENS HEARING BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON EDUCATION AND LABOR U.S. HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED TENTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION HEARING HELD IN WASHINGTON, DC, APRIL 24, 2008 Serial No. 110–89 Printed for the use of the Committee on Education and Labor ( Available on the Internet: http://www.gpoaccess.gov/congress/house/education/index.html U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 41–839 PDF WASHINGTON : 2008 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate 0ct 09 2002 15:49 Jul 16, 2008 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 G:\DOCS\110TH\FC\110-89\41839.TXT HBUD1 PsN: DICK COMMITTEE ON EDUCATION AND LABOR GEORGE MILLER, California, Chairman Dale E. Kildee, Michigan, Vice Chairman Howard P. ‘‘Buck’’ McKeon, California, Donald M. Payne, New Jersey Senior Republican Member Robert E. Andrews, New Jersey Thomas E. Petri, Wisconsin Robert C. ‘‘Bobby’’ Scott, Virginia Peter Hoekstra, Michigan Lynn C. Woolsey, California Michael N. Castle, Delaware Rube´n Hinojosa, Texas Mark E. Souder, Indiana Carolyn McCarthy, New York Vernon J. Ehlers, Michigan John F. Tierney, Massachusetts Judy Biggert, Illinois Dennis J. Kucinich, Ohio Todd Russell Platts, Pennsylvania David Wu, Oregon Ric Keller, Florida Rush D. Holt, New Jersey Joe Wilson, South Carolina Susan A. Davis, California John Kline, Minnesota Danny K. Davis, Illinois Cathy McMorris Rodgers, Washington Rau´ l M. -

Usef-I Q2 2021

Units Cost Market Value U.S. EQUITY FUND-I U.S. Equities 88.35% Domestic Common Stocks 10X GENOMICS INC 5,585 868,056 1,093,655 1ST SOURCE CORP 249 9,322 11,569 2U INC 301 10,632 12,543 3D SYSTEMS CORP 128 1,079 5,116 3M CO 11,516 2,040,779 2,287,423 A O SMITH CORP 6,897 407,294 496,998 AARON'S CO INC/THE 472 8,022 15,099 ABBOTT LABORATORIES 24,799 2,007,619 2,874,948 ABBVIE INC 17,604 1,588,697 1,982,915 ABERCROMBIE & FITCH CO 1,021 19,690 47,405 ABIOMED INC 9,158 2,800,138 2,858,303 ABM INDUSTRIES INC 1,126 40,076 49,938 ACACIA RESEARCH CORP 1,223 7,498 8,267 ACADEMY SPORTS & OUTDOORS INC 1,036 35,982 42,725 ACADIA HEALTHCARE CO INC 2,181 67,154 136,858 ACADIA REALTY TRUST 1,390 24,572 30,524 ACCO BRANDS CORP 1,709 11,329 14,749 ACI WORLDWIDE INC 6,138 169,838 227,965 ACTIVISION BLIZZARD INC 13,175 839,968 1,257,422 ACUITY BRANDS INC 1,404 132,535 262,590 ACUSHNET HOLDINGS CORP 466 15,677 23,020 ADAPTHEALTH CORP 1,320 39,475 36,181 ADAPTIVE BIOTECHNOLOGIES CORP 18,687 644,897 763,551 ADDUS HOMECARE CORP 148 13,034 12,912 ADOBE INC 5,047 1,447,216 2,955,725 ADT INC 3,049 22,268 32,899 ADTALEM GLOBAL EDUCATION INC 846 31,161 30,151 ADTRAN INC 892 10,257 18,420 ADVANCE AUTO PARTS INC 216 34,544 44,310 ADVANCED DRAINAGE SYSTEMS INC 12,295 298,154 1,433,228 ADVANCED MICRO DEVICES INC 14,280 895,664 1,341,320 ADVANSIX INC 674 15,459 20,126 ADVANTAGE SOLUTIONS INC 1,279 14,497 13,800 ADVERUM BIOTECHNOLOGIES INC 1,840 7,030 6,440 AECOM 5,145 227,453 325,781 AEGLEA BIOTHERAPEUTICS INC 287 1,770 1,998 AEMETIS INC 498 6,023 5,563 AERSALE CORP -

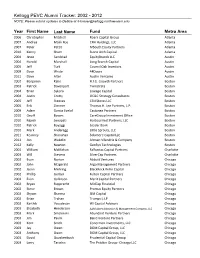

Kellogg PEVC Alumni Tracker: 2002 - 2012 NOTE: Please Submit Updates to Debbie at [email protected]

Kellogg PEVC Alumni Tracker: 2002 - 2012 NOTE: Please submit updates to Debbie at [email protected] Year First Name Last Name Fund Metro Area 2006 Christopher Mitchell Roark Capital Group Atlanta 2007 Andrea Malik Roe CRH Holdings, LLC Atlanta 2007 Peter Pettit MSouth Equity Partners Atlanta 2010 Kenny Shum Stone Arch Capital Atlanta 2004 Jesse Sandstad EquityBrands LLC Austin 2004 Harold Marshall Long Branch Capital Austin 2005 Jeff Turk Council Oak Investors Austin 2009 Dave Wride 44Doors Austin 2011 Dave Alter Austin Ventures Austin 2002 Benjamin Kahn H.I.G. Growth Partners Boston 2003 Patrick Davenport Twinstrata Boston 2004 Brian Sykora Lineage Capital Boston 2004 Justin Crotty OC&C Strategy Consultants Boston 2005 Jeff Steeves CSN Stores LLC Boston 2005 Erik Zimmer Thomas H. Lee Partners, L.P. Boston 2009 Adam Garcia Evelof Castanea Partners Boston 2010 Geoff Bowes CareGroup Investment Office Boston 2010 Rajesh Senapati HarbourVest Partners, LLC Boston 2010 Patrick Boyaggi Leader Bank Boston 2010 Mark Anderegg Little Sprouts, LLC Boston 2011 Kearney Shanahan Solamere Capital LLC Boston 2012 Jon Wakelin Altman Vilandrie & Company Boston 2012 Kelly Newton GenSyn Technologies Boston 2003 William McMahan Falfurrias Capital Partners Charlotte 2003 Will Stevens SilverCap Partners Charlotte 2002 Evan Norton Abbott Ventures Chicago 2002 John Fitzgerald Argo Management Partners Chicago 2002 Jason Mehring BlackRock Kelso Capital Chicago 2002 Phillip Gerber Fulton Capital Partners Chicago 2002 Evan Gallinson Merit Capital Partners -

Aspen Education Group

ASPEN ACHIEVEMENT ACADEMY A division of Aspen Education Group SUPPLEMENTAL DOCUMENTS for admission Please note: The initial application needs to be completed & submitted on line at www.aspenacademy.com Please complete these supplemental documents in addition to the application and fax to 435.836.2477 If you have questions contact your admissions counselor at 435.836.2472 ASPEN ACHIEVEMENT ACADEMY PO Box 400 / 98 South Main Street Loa, UT 84747 800.283.8334 Admissions Office 435.836.2472 Main Office 435.836.2477 FAX www.aspenacademy.com A Aspen Education Group AUTHORIZATION FOR USE OR DISCLOSURE OF HEALTH INFORMATION This form is a RELEASE OF INFORMATION FORM. Completion of this document authorizes the disclosure and/or use of individually identifiable health information, as set forth below, consistent with State and Federal law concerning the privacy of such information. Failure to provide all information requested may invalidate this Authorization. USE AND DISCLOSURE OF HEALTH INFORMATION I hereby authorize the use or disclosure of my health information as follows: Patient Name: Persons/Organizations authorized to use or disclose the information: 1 Aspen Achievement Academy Persons/Organizations authorized to receive the information: Aspen Achievement Academy Name/Title: Name/Title: Address: Address: City: City: State: Zip: State: Zip: E-mail address: E-mail address: Phone ( ) Phone ( ) Purpose of requested use or disclosure: 2 This Authorization applies to the following information (select only one of the following):3 All health information pertaining to any medical history, mental or physical condition and treatment received. [Optional] Except: Only the following records or types of health information (including any dates): EXPIRATION This Authorization expires [insert date or event]:4 NOTICE OF RIGHTS AND OTHER INFORMATION I may refuse to sign this Authorization. -

Private Equity Benchmark Report

Preqin Private Equity Benchmarks: All Private Equity Benchmark Report As of 31st March 2014 alternative assets. intelligent data. Preqin Private Equity Benchmarks: All Private Equity Benchmark Report As of 31st March 2014 Report Produced on 9th October 2014 This publication is not included in the CLA Licence so you must not copy any portion of it without the permission of the publisher. All rights reserved. The entire contents of the report are the Copyright of Preqin Ltd. No part of this publication or any information contained in it may be copied, transmitted by any electronic means, or stored in any electronic or other data storage medium, or printed or published in any document, report or publication, without the express prior written approval of Preqin Ltd. The information presented in the report is for information purposes only and does not constitute and should not be construed as a solicitation or other offer, or recommendation to acquire or dispose of any investment or to engage in any other transaction, or as advice of any nature whatsoever. If the reader seeks advice rather than information then he should seek an independent fi nancial advisor and hereby agrees that he will not hold Preqin Ltd. responsible in law or equity for any decisions of whatever nature the reader makes or refrains from making following its use of the report. While reasonable efforts have been used to obtain information from sources that are believed to be accurate, and to confi rm the accuracy of such information wherever possible, Preqin Ltd. Does not make any representation or warranty that the information or opinions contained in the report are accurate, reliable, up-to-date or complete. -

The Brief Mergermarket’S Weekly Private Equity Round-Up

The Brief mergermarket’s Weekly Private Equity Round-Up 4 December 2009 | Issue 41 Editorial 1 The Noticeboard 2 Private Equity Opportunities 3 Deals of the Week 9 Pipeline 16 Statistics 19 League & Activity Tables 22 Top Deals 31 Investor Profile: Blackstone Group Holdings LLC 34 Notes & Contacts 36 The Week That Was..... The last seven days: private equity in review Over the past seven days, global private equity deal Mongolia-based Gobi Coal and Energy from En+ Group making was steady but somewhat unspectacular with for US$25m. Although the value of the deal falls firmly 15 transactions coming to the market, worth a collective in the lower end of the market, it is the largest private US$2.57bn. The top deal of the week was seen in Italy equity-related deal announced in Mongolia this decade. where Bridgepoint Capital and AXA Private Equity moved to acquire the gaming business of Snai, the company Deal flow over the second half of 2009 has certainly engaged in the design, construction and provision of suggested that private equity houses are becoming technology and services in the gambling industry, for a increasingly willing to return to the market after the total consideration of US$898m. global financial crisis. However, this week there was a sharp reminder to the asset class that the effects of The deal could prove to be an astute investment by the the economic downturn will be felt for some time yet buyout houses with Italy’s gaming market the second with beleaguered buyout firm Candover announcing largest in Europe and tipped to see annual growth of that it has agreed with investors to terminate the €3bn around 4-6% over the next five years.