Therapeutic Boarding Schools, Wilderness Camps, Boot Camps and Behavior Modification Facilities, Have Sprung up in Greater Numbers Since the 1990S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

177-May:Masternl 1-20.Qxd

Places for Struggling Teens™ Published by Woodbury Reports, Inc.™ “It is more important to get it right, than to get it first.” May 2009 - Issue #177 NORTHWEST GET-TOGETHER IS UNIQUE By: Lon Woodbury We are striving to make the upcoming Get-Together on May 15 as unique as the previous three have been. The goal is to emphasize networking and socializing time in a fairly small, informal and interactive setting among everybody who is interested in the network of private, parent choice schools, programs and services, Yes, there will be interesting and valuable presentations, but that is only part of the program. Of at least equal importance is the chance to visit with old friends and make news ones. Those of us who work in this network frequently attend conferences, primarily the IECA and NATSAP conferences. They are invaluable and enjoyable. However, they are usually in expensive hotels or conference centers in cities, and there is a frantic pace from the large numbers attending and being packed with presentations. Each conference is developed around one type of professional (The IECA focuses on the needs of Educational Consultants, NATSAP for school administrative staff….). Frequently, an attendee must choose between whether to have that needed and long-awaited conversation with a colleague or to attend a breakout session occurring at the same time with information important for the attendee’s job. Or, they sometimes take advantage of exploring or shopping in the nearby area. At the NorthWest Get-Together, we are consciously trying to break out of these patterns. The concept was inspired by a meeting called years ago by Rob Spear, then President of the CEDU schools. -

Directory National Association of Therapeutic Schools and Programs

NATSAP 2009 Directory National Association of Therapeutic Schools and Programs NATSAP 2009 DIRECTORY e only bee, th s th at e i m op ak H es “ h o n e y w i t h o u t f l o w e r s , ” - R o b e r t G r e e n I n g e r s o l l Schools and Programs for Young People Experiencing Behavioral, Psychiatric and Learning Diffi culties NATSAP • www.natsap.org • (301) 986-8770 1 NATSAP 2009 Directory NATSAP 2009 Directory TABLE OF CONTENTS Page About NATSAP ............................................................................................3 NATSAP Ethical Principles ..........................................................................4 Program Definitions ......................................................................................5-6 NATSAP Alumni Advisory Council ............................................................10 Questions to Ask Before Making a Final Placement ....................................11-14 Program Listing By Name ............................................................................11-14 Program Directory Listings ...........................................................................16-187 Program Listing By State ...............................................................................................188-192 By Gender ...........................................................................................193-195 By Age ................................................................................................195-199 By Program Type ................................................................................200-202 -

Aspen Education Group

ASPEN ACHIEVEMENT ACADEMY A division of Aspen Education Group SUPPLEMENTAL DOCUMENTS for admission Please note: The initial application needs to be completed & submitted on line at www.aspenacademy.com Please complete these supplemental documents in addition to the application and fax to 435.836.2477 If you have questions contact your admissions counselor at 435.836.2472 ASPEN ACHIEVEMENT ACADEMY PO Box 400 / 98 South Main Street Loa, UT 84747 800.283.8334 Admissions Office 435.836.2472 Main Office 435.836.2477 FAX www.aspenacademy.com A Aspen Education Group AUTHORIZATION FOR USE OR DISCLOSURE OF HEALTH INFORMATION This form is a RELEASE OF INFORMATION FORM. Completion of this document authorizes the disclosure and/or use of individually identifiable health information, as set forth below, consistent with State and Federal law concerning the privacy of such information. Failure to provide all information requested may invalidate this Authorization. USE AND DISCLOSURE OF HEALTH INFORMATION I hereby authorize the use or disclosure of my health information as follows: Patient Name: Persons/Organizations authorized to use or disclose the information: 1 Aspen Achievement Academy Persons/Organizations authorized to receive the information: Aspen Achievement Academy Name/Title: Name/Title: Address: Address: City: City: State: Zip: State: Zip: E-mail address: E-mail address: Phone ( ) Phone ( ) Purpose of requested use or disclosure: 2 This Authorization applies to the following information (select only one of the following):3 All health information pertaining to any medical history, mental or physical condition and treatment received. [Optional] Except: Only the following records or types of health information (including any dates): EXPIRATION This Authorization expires [insert date or event]:4 NOTICE OF RIGHTS AND OTHER INFORMATION I may refuse to sign this Authorization. -

Ever Unconventional, Long Controversial | Local/State | the Bulletin Page 1 of 6

Ever unconventional, long controversial | Local/State | The Bulletin Page 1 of 6 Ever unconventional, long controversial The school’s history is a twisted one, involving atypical therapy methods and company mergers, good intentions and success stories, but also cases of what some, including the state, call abuse. The story behind the academy’s closure. By Keith Chu / The Bulletin Published: November 15. 2009 4:00AM PST An era ended when Mount Bachelor Academy closed Nov. 3, following allegations of child abuse by the state Department of Human Services. The private school for troubled teens, located 26 miles east of Prineville, was one of the last of its kind — a school whose methods originated in the Synanon self-help group, which was widely considered a cult by the late 1970s. It’s also a school that counts hundreds, if not thousands, Rob Kerr / The Bulletin file photo of devoted graduates and parents who swear that Mount The academy’s better days ... Many students and Bachelor Academy put their children on the right track, or parents attest to Mount Bachelor Academy’s successes. even saved their lives. In 2003, The Bulletin interviewed 18-year-old Pedro Macias and his mother, Sally, of Mexico City, on And for years, MBA was a flagship of Aspen Education graduation day. The “old” Pedro had been kicked out of Group, a company that grew to become one of the biggest school and had a problem with marijuana. But after his providers of therapeutic, emotional-growth and weight-loss time at the academy, “it’s an incredible change,” his facilities in the U.S. -

185-January:Masternl 1-20.Qxd

Places for Struggling Teens™ Published by Woodbury Reports, Inc.™ “It is more important to get it right, than to get it first.” January 2010 - Issue #185 JEFFREY M. GEORGI, CAFETY AND THE ADOLESCENT BRAIN By Lon Woodbury The highlight of the recent Independent Educational Consultants Association (IECA) conference in Charlotte, NC, was a three hour presentation on Saturday morning November 14, 2009, by Jeffrey M. Georgi on the Adolescent Brain. Georgi is the Clinical Director of the Duke University Addictions Program, an author and a popular speaker. The ballroom was full, which is remarkable considering it was on a Saturday morning after a long and exhausting conference. The wide attendance was a powerful testimony to his expertise and knowledge of the subject. The attendees were not disappointed, and many remarked to me how much they had learned from the presentation. A major emphasis, since he was speaking to a group of professional educators, was outlining the development of the brains of adolescents. A major point was that a person’s brain was not fully developed until a person is into his/her twenties. This conclusion from exhaustive research tells us that many of the impulsive, silly and self-destructive decisions adolescents make are because their brains are not yet fully developed. Their forebrain is not developed enough to put a check on impulsive behaviors. In a sense, when an adolescent does something dumb, it’s because their brain has not developed enough to think through the consequences. “If it feels good, do it” seems to be the mantra for the adolescent brain. -

Ernst & Young Entrepreneur of the Year 2007

Isaac Larian MGA Entertainment Ernst & Young Entrepreneur Of The Year 2007 Presenting Sponsor National Sponsors !@# When just being nominated is an honor. Winning has its advantages, but with the Ernst & Young Entrepreneur Of The Year® awards, it is truly an accomplishment just to be nominated. Bank of America salutes all the regional winners for impacting the business world and our communities. Congratulations. bankofamerica.com Investment banking and capital markets products and services provided by Banc of America Securities LLC, a subsidiary of Bank of America Corporation and member NYSE/FINRA/SIPC. ©2007 Bank of America Corporation. AD-10-07-0198_8.5x11_r.indd 1 10/29/07 5:15:06 PM Success Is a Journey n an age where faster, better, cheaper has become a mantra, entrepreneurial growth companies continually find better ways to develop, grow, and prosper. They take Iwords like “can’t” and “no” and turn them into motivational tools. Telling an entrepreneur that something can’t be done is a surefire way to create a solution. And as these innovative men and women grow their companies into market leaders, they’re making valuable contributions to industries, economies, and individual lives. Ernst & Young’s Strategic Growth Markets practice understands what entrepreneurs face as they shepherd an idea to its full potential. We are the leader in serving the Russell 3000, high-growth private companies, IPO-bound companies, and companies with significant venture capital or private equity investments. We’re committed to serving entrepreneurial companies throughout their life cycles—from the emerging stage through their growth into successful market leaders. -

Copyright 2008 Thomas J. Croke and Associates, Inc. All Rights Reserved

Copyright 2008 Thomas J. Croke and Associates, Inc. All rights reserved. November 14, 2008 version Name of School/Program Type of School/Program Academy at Canyon Creek Residential Treatment Center Academy at Sisters Emotional Growth Boarding School Academy at Swift River Therapeutic Boarding School Academy of the Sierras Specialized Boarding School Adirondack Leadership Expeditions Wilderness Program Advanced Recovery Center Transitional Independent Living Program Alldredge Wilderness Journey Wilderness Program Alpine Academy Residential Treatment Center ANASAZI Foundation Outdoor Behavioral Healthcare Program Ascent Wilderness Program Aspen Achievement Academy Wilderness Program Aspen Ranch Residential Treatment Center Aspiro Wilderness Program Auldern Academy Personal Growth Boarding School Benchmark Young Adult School Transitional Independent Living Program and Young Adult Program Betton House Transitional Independent Living Birdseye Boys Ranch Residential Treatment Program Blackwater Outdoor Experiences Wilderness Program Boulder Creek Academy Therapeutic Boarding School Bridges Academy Emotional Growth School Bromley Brook School Emotional Growth School Building Bridges Small Residential Program Buxmont Academy Small Residential Program & Residential Treatment Center Big Horn Basin Therapeutic Program Bill Lane & Associates Adoloscent Transport Services CALO (Change Academy Lake of the Ozarks) Residential Treatment Center Caron Adolescent Residential Treatment Center Residential Treatment Center Catalyst Residential Treatment, LLC -

167-July:Masternl 1-32.Qxd

Places for Struggling Teens™ Published by Woodbury Reports, Inc.™ “It is more important to get it right, than to get it first.” July 2008 - Issue #167 WHAT ABOUT THE PARENTS? By: Lon Woodbury Parents have the primary responsibility for raising children in our society. This includes deciding which school or treatment facility the child should attend for whatever reasons the parent thinks are important. This responsibility is not absolute however since parents must conform to certain basic standards like mandatory school attendance laws and laws against abuse, neglect, abandonment, etc. The schools and programs they might choose must and should conform to these basic standards as well. However, for the most part our laws and the courts have protected this right and responsibility of parents to raise their children in the way the parents think best. In general, the more options parents have to choose from, the better choices they are likely to make. This is part of what in this country we call freedom, that is, as some have stated in other issues, “Freedom is choice!” Congressman Miller, in the first draft of his HR 5876, seems to be focusing on restricting parents’ right to choose regarding when a child needs residential placement. This isn’t stated in so many words of course, but the intent of the proposed legislation is to allow parents to choose only those schools and programs that have the stamp of approval from the federal government. How much restriction depends on the wording of the final legislation, the biases of the federal employee regulation writers, and the intentions of the federal regulators assigned to monitor conformity to the written regulations. -

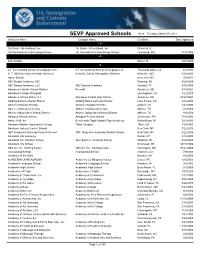

SEVP Approved Schools As of Tuesday, March 08, 2011 Institution Name Campus Name City/State Date Approved - 1

SEVP Approved Schools As of Tuesday, March 08, 2011 Institution Name Campus Name City/State Date Approved - 1 - 1st Choice International, Inc. 1st Choice International, Inc. Glenview, IL 1st International Cosmetology School 1st International Cosmetology School Lynnwood, WA 11/5/2004 - 4 - 424 Aviation Miami, FL 10/7/2009 - A - A F International School of Languages Inc. A F International School of Languages In Thousand Oaks, CA 6/3/2003 A. T. Still University of Health Sciences Kirksville Coll of Osteopathic Medicine Kirksville, MO 3/10/2003 Aaron School New York, NY 3/4/2011 ABC Beauty Academy, INC. Flushing, NY 4/28/2009 ABC Beauty Academy, LLC ABC Beauty Academy Garland, TX 3/30/2006 Aberdeen Catholic School System Roncalli Aberdeen, SD 8/14/2003 Aberdeen College of English Los Angeles, CA 1/22/2010 Aberdeen School District 6-1 Aberdeen Central High School Aberdeen, SD 10/27/2004 Abiding Savior Lutheran School Abiding Savior Lutheran School Lake Forest, CA 4/16/2003 Abilene Christian Schools Abilene Christian Schools Abilene, TX 1/31/2003 Abilene Christian University Abilene Christian University Abilene, TX 2/5/2003 Abilene Independent School District Abilene Independent School District Abilene, TX 8/8/2004 Abington Friends School Abington Friends School Jenkintown, PA 7/15/2003 Above It All, Inc Benchmark Flight /Hawaii Flight Academy Kailua-Kona, HI 12/3/2003 Abraham Baldwin Agricultural College Tifton Campus Tifton, GA 1/10/2003 Abraham Joshua Heschel School New York, NY 1/22/2010 ABT Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis School ABT Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis School New York, NY 6/22/2006 Abundant Life Academy Kanab, UT 2/15/2008 Abundant Life Christian School Abundant Life Christian School Madison, WI 9/14/2004 Abundant Life School Sherwood, AR 10/25/2006 ABX Air, Inc. -

A Multi-Center Study of Private Residential Treatment Outcomes

PRIVATE RESIDENTIAL TREATMENT OUTCOMES A Multi-Center Study of Private Residential Treatment Outcomes Ellen Behrens, Ph.D. Canyon Research & Consulting Kristin Satterfield, M.D., Ph.D. University of Utah Correspondence should be addressed to Dr. Ellen Behrens, E-mail: [email protected] Abstract This paper presents the results from a multi-center study on outcomes for youth treated in private residential treatment programs. The sample of 1,027 adolescents and their parents was drawn from nine private residential programs. Hierarchical linear modeling indicated that both adolescents and parents reported a significant reduction in problems on each global measure of psycho-social functioning from the time of admission up until a year after leaving the program (e.g., Total Problems Scores, Internalizing Scales, and Externalizing Scales of the Child Behavior CheckList, CBCL, and Youth Self-Report, YSR). Furthermore, youth and parents reported that the youth improved on all syndromes between the point of admission and discharge (YSR and CBCL syndrome scales: Anxious/Depressed, Withdrawn/Depressed, Somatic Complaints, Thought Problems, Attention Problems, Aggressive Behavior, Rule- Breaking) and that most of the syndromes remained stable and within the normal range for up to one year after discharge from treatment. JTSP • 29 PRIVATE RESIDENTIAL TREATMENT OUTCOMES A Multi-Center Study of Private Residential Treatment Outcomes Since the early 1990’s hundreds of private residential programs have been established in the United States. Outcomes of youth treated in these programs are largely unknown (Friedman, Pinto, Behar, Bush, Chirolla, Epstein … & Young, 2006). Previous research has focused almost entirely on public residential treatment programs (RTPs) (Curry, 2004; Curtis, Alexander, & Longhofer, 2001; Hair, 2005; Leichtman, Leichtman, Barbet, & Nese, 2001; Lieberman, 2004; Whittaker, 2004). -

It's ALL the RAGE!

It’s All the rage! An in-depth look at behavior modification in the United States By Angela Smith (Photo by HEAL Kentucky Chapter, March, 2008) All Rights Reserved. This book and any part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system without the expressed written permission of the author if done without profit and source is cited. Please direct requests, questions, comments, or reviews to Angela Smith, (c/o): HEAL 126 SW 148 th St. Ste C100-422 Seattle, WA 98166-1984 Chapters Page * Chapter list and Dedication 2 Section one 3 1. Introduction 3 2. Behavior modification and discipline 6 3. Behavioral engineering and controls 14 4. Scientific evidence 19 5. Fraud, abuse, rape, torture, and death 30 Section two 73 6. Legal issues: civil and criminal 73 7. Government corruption 84 8. Government action 91 9. Reasons for hope and immediate action 96 Dedication This book is dedicated to all of the survivors, victims, and families defrauded, abused, raped, tortured, and/or killed by the behavior modification industry. Appreciation Special Thanks To: Catherine Smith Patrick Liberg, HEAL Illinois Tony Connelly, HEAL Kentucky John Giesler, HEAL Iowa Peter Orozco Earle, HEAL Wisconsin Sonny B. Emily Adams, HEAL Colorado Richard Meehan, HEAL New York N.R. Mike and Carla Plotycia The Taylor Family International Survivors Action Committee Teen Advocates USA Thomas Mark Burton, Attorney at Law …and all the survivors, victims, and families who provided information for this project. -

Journal of Therapeutic Schools & Programs

JTSP JTSP ARTICLES (CON’T.) u 2007 2007 JTSP Equal Experts: Peer Reflecting Teams In Residential Group Therapy John Hall, LMFT . 119 u u Journal of Therapeutic Experience, Strength and Hope: One Mother and Daughter’s Journey Through Addiction and Recovery II Volume Julianna Bissette and Anna Bissette. .129 Schools & Programs Subscribe to JTSP . 144 u u NATSAP Directory Order Form. 145. 2007 u VOLUME II u NUMBER I Number I Number Call for Papers. 146 Permissions and Copyright Information for Potential Authors . 147 AUTHORS. 5 Instructions for Authors . 148. ARTICLES NATSAP Ethical Principles. 149 Dealing With Issues of Program Effectiveness, Cost Benefit Analysis, and Treatment Fidelity: The Development of the NATSAP Research and Evaluation Network Michael Gass, Ph. D., LMFT & Michael Young, M.Ed . .8 Journal of Therapeutic Schools & Programs A Lost Ring: Keynote Address At The 2007 NATSAP Conference National.Association.of John A. McKinnon, MD . .25 ...Therapeutic.Schools.&.Programs 126.N ..Marina.St .,.Ste ..2 Residential Treatment and the Missing Axis Prescott,.AZ..86301 John L. Santa, Ph.D.. .45 So You Want To Run An Outcome Study? The Challenges To Measuring Adolescent Residential Treatment Outcomes John McKay, J.D., M.S. 63 Longitudinal Family and Academic Outcomes in Residential Programs: How Students Function in Two Important Areas of Their Lives, Ellen N. Behrens, Ph.D. and Kristin M. Satterfield, Ph.D. .81 TO: Recognizing and Treating Reactive Attachment Disorder Peter M. Lake, MD. 95 Differentiating Bipolar Disorder and Borderline Personality Disorder: Utilizing Effective Clinical Interviewing and the Treatment Environment to Assist with Diagnosis Norma Clarke, MD and Nancy Diacon, MA, ARPN, BC.