Case Study from Thailand

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(Unofficial Translation) Order of the Centre for the Administration of the Situation Due to the Outbreak of the Communicable Disease Coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) No

(Unofficial Translation) Order of the Centre for the Administration of the Situation due to the Outbreak of the Communicable Disease Coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) No. 1/2564 Re : COVID-19 Zoning Areas Categorised as Maximum COVID-19 Control Zones based on Regulations Issued under Section 9 of the Emergency Decree on Public Administration in Emergency Situations B.E. 2548 (2005) ------------------------------------ Pursuant to the Declaration of an Emergency Situation in all areas of the Kingdom of Thailand as from 26 March B.E. 2563 (2020) and the subsequent 8th extension of the duration of the enforcement of the Declaration of an Emergency Situation until 15 January B.E. 2564 (2021); In order to efficiently manage and prepare the prevention of a new wave of outbreak of the communicable disease Coronavirus 2019 in accordance with guidelines for the COVID-19 zoning based on Regulations issued under Section 9 of the Emergency Decree on Public Administration in Emergency Situations B.E. 2548 (2005), by virtue of Clause 4 (2) of the Order of the Prime Minister No. 4/2563 on the Appointment of Supervisors, Chief Officials and Competent Officials Responsible for Remedying the Emergency Situation, issued on 25 March B.E. 2563 (2020), and its amendments, the Prime Minister, in the capacity of the Director of the Centre for COVID-19 Situation Administration, with the advice of the Emergency Operation Center for Medical and Public Health Issues and the Centre for COVID-19 Situation Administration of the Ministry of Interior, hereby orders Chief Officials responsible for remedying the emergency situation and competent officials to carry out functions in accordance with the measures under the Regulations, for the COVID-19 zoning areas categorised as maximum control zones according to the list of Provinces attached to this Order. -

The Mineral Industry of Thailand in 2008

2008 Minerals Yearbook THAILAND U.S. Department of the Interior August 2010 U.S. Geological Survey THE MINERAL INDUS T RY OF THAILAND By Lin Shi In 2008, Thailand was one of the world’s leading producers by 46% to 17,811 t from 32,921 t in 2007. Production of iron of cement, feldspar, gypsum, and tin. The country’s mineral ore and Fe content (pig iron and semimanufactured products) production encompassed metals, industrial minerals, and each increased by about 10% to 1,709,750 t and 855,000 t, mineral fuels (table 1; Carlin, 2009; Crangle, 2009; Potter, 2009; respectively; manganese output increased by more than 10 times van Oss, 2009). to 52,700 t from 4,550 t in 2007, and tungsten output increased by 52% to 778 t from 512 t in 2007 (table 1). Minerals in the National Economy Among the industrial minerals, production of sand, silica, and glass decreased by 41%; that of marble, dimension stone, and Thailand’s gross domestic product (GDP) in 2008 was fragment, by 22%; and pyrophyllite, by 74%. Production of ball valued at $274 billion, and the annual GDP growth rate was clay increased by 166% to 1,499,993 t from 563,353 t in 2007; 2.6%. The growth rate of the mining sector’s portion of the calcite and dolomite increased by 22% each; crude petroleum GDP increased by 0.6% compared with that of 2007, and that oil increased by 9% to 53,151 barrels (bbl) from 48,745 bbl in of the manufacturing sector increased by 3.9%. -

Sukhothai Phitsanulok Phetchabun Sukhothai Historical Park CONTENTS

UttaraditSukhothai Phitsanulok Phetchabun Sukhothai Historical Park CONTENTS SUKHOTHAI 8 City Attractions 9 Special Events 21 Local Products 22 How to Get There 22 UTTARADIT 24 City Attractions 25 Out-Of-City Attractions 25 Special Events 29 Local Products 29 How to Get There 29 PHITSANULOK 30 City Attractions 31 Out-Of-City Attractions 33 Special Events 36 Local Products 36 How to Get There 36 PHETCHABUN 38 City Attractions 39 Out-Of-City Attractions 39 Special Events 41 Local Products 43 How to Get There 43 Sukhothai Sukhothai Uttaradit Phitsanulok Phetchabun Phra Achana, , Wat Si Chum SUKHOTHAI Sukhothai is located on the lower edge of the northern region, with the provincial capital situated some 450 kms. north of Bangkok and some 350 kms. south of Chiang Mai. The province covers an area of 6,596 sq. kms. and is above all noted as the centre of the legendary Kingdom of Sukhothai, with major historical remains at Sukhothai and Si Satchanalai. Its main natural attraction is Ramkhamhaeng National Park, which is also known as ‘Khao Luang’. The provincial capital, sometimes called New Sukhothai, is a small town lying on the Yom River whose main business is serving tourists who visit the Sangkhalok Museum nearby Sukhothai Historical Park. CITY ATTRACTIONS Ramkhamhaeng National Park (Khao Luang) Phra Mae Ya Shrine Covering the area of Amphoe Ban Dan Lan Situated in front of the City Hall, the Shrine Hoi, Amphoe Khiri Mat, and Amphoe Mueang houses the Phra Mae Ya figure, in ancient of Sukhothai Province, this park is a natural queen’s dress, said to have been made by King park with historical significance. -

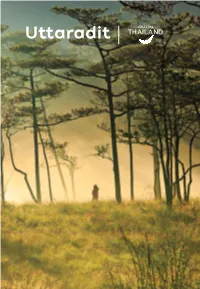

Uttaradit Uttaradit Uttaradit

Uttaradit Uttaradit Uttaradit Namtok Sai Thip CONTENTS HOW TO GET THERE 7 ATTRACTIONS 8 Amphoe Mueang Uttaradit 8 Amphoe Laplae 11 Amphoe Tha Pla 16 Amphoe Thong Saen Khan 18 Amphoe Nam Pat 19 EVENTS & FESTIVALS 23 LOCAL PRODUCTS AND SOUVENIRS 25 INTERESTING ACTIVITIES 27 Agro-tourism 27 Golf Course 27 EXAMPLES OF TOUR PROGRAMMES 27 FACILITIES IN UTTARADIT 28 Accommodations 28 Restaurants 30 USEFUL CALLS 32 Wat Chedi Khiri Wihan Uttaradit Uttaradit has a long history, proven by discovery South : borders with Phitsanulok. of artefacts, dating back to pre-historic times, West : borders with Sukhothai. down to the Ayutthaya and Thonburi periods. Mueang Phichai and Sawangkhaburi were HOW TO GET THERE Ayutthaya’s most strategic outposts. The site By Car: Uttaradit is located 491 kilometres of the original town, then called Bang Pho Tha from Bangkok. Two routes are available: It, which was Mueang Phichai’s dependency, 1. From Bangkok, take Highway No. 1 and No. 32 was located on the right bank of the Nan River. to Nakhon Sawan via Phra Nakhon Si Ayutthaya, It flourished as a port for goods transportation. Ang Thong, Sing Buri, and Chai Nat. Then, use As a result, King Rama V elevated its status Highway No. 117 and No. 11 to Uttaradit via from Tambon or sub-district into Mueang or Phitsanulok. town but was still under Mueang Phichai. King 2. From Bangkok, drive to Amphoe In Buri via Rama V re-named it Uttaradit, literally the Port the Bangkok–Sing Buri route (Highway No. of the North. Later Uttaradit became more 311). -

THAILAND Last Updated: 2006-12-05

Vitamin and Mineral Nutrition Information System (VMNIS) WHO Global Database on Anaemia The database on Anaemia includes data by country on prevalence of anaemia and mean haemoglobin concentration THAILAND Last Updated: 2006-12-05 Haemoglobin (g/L) Notes Age Sample Proportion (%) of population with haemoglobin below: Mean SD Method Reference General Line Level Date Region and sample descriptor Sex (years) size 70 100 110 115 120 130 S 2002 Ubon Ratchathani province: SAC B 6.00- 12.99 567 C 5227 * 1 LR 1999 Songkhla Province: Hat Yai rural area: SAC: Total B 6.00- 13.99 397 A 3507 * 2 Songkhla Province: Hat Yai rural area: SAC by inter B 6.00- 13.99 140 121 10 3 Songkhla Province: Hat Yai rural area: SAC by inter B 6.00- 13.99 134 121 9 4 Songkhla Province: Hat Yai rural area: SAC by inter B 6.00- 13.99 123 122 10 5 S 1997P Northeast-Thailand: Women F 15.00- 45.99 607 17.3 A 2933 * 6 SR 1996 -1997 Sakon Nakhon Province: All B 1.00- 90.99 837 132 14 A 3690 * 7 Sakon Nakhon Province: Adults: Total B 15.00- 60.99 458 139 14 8 Sakon Nakhon Province: Elderly: Total B 61.00- 90.99 35 113 11 9 Sakon Nakhon Province: Children: Total B 1.00- 14.99 344 129 13 10 Sakon Nakhon Province: All by sex F 1.00- 90.99 543 11 Sakon Nakhon Province: All by sex M 1.00- 90.99 294 12 Sakon Nakhon Province: Adults by sex F 15.00- 60.99 323 13 Sakon Nakhon Province: Adults by sex M 15.00- 60.99 135 14 Sakon Nakhon Province: Children by sex F 1.00- 14.99 194 15 Sakon Nakhon Province: Children by sex M 1.00- 14.99 150 16 L 1996P Chiang Mai: Pre-SAC B 0.50- 6.99 340 -

Gas Stations

Gas Stations Chuchawal Royal Haskoning was responsible for the construction Country: management and site supervision for 3 Q8 Gas filling stations; Kaeng Koi Thailand District in Saraburi Province, Bangyai District in Nonthaburi Province and in Chonburi. Client: Q8 The Q8 gas stations are constructed on 4-rai areas. Each station comprises a 350 m2 convenience store, 4 multi-product fuel dispensers, canopies, public Period: toilets, customers’ relaxation area with shelter, sign board and staff housing. 2002 Chuchawal Royal Haskoning 8th Flr., Asoke Towers, 219/25 Sukhumvit 21, Bangkok 10110. Tel: +66 259 1186. Fax: +66 260 0230 Internet: www.chuchawalroyalhaskoning.com Reference: T/0232 HomePro Store HomePro is a very successful company engaged in the sale of hardware, Country: furniture and home improvement products both for the retail market and for Bangkok, Thailand small contractors. Several new stores were built in 2002 and 2003. Client: Chuchawal Royal Haskoning, in cooperation with its sister company, Interior Home Product Center PCL. Architecture 103, provided project management and construction management and site supervision services for the construction of their new stores. Period: The HomePro – Rama II store comprises 3 buildings with a total retail area of 2002 10,500m2. Chuchawal Royal Haskoning 8th Flr., Asoke Towers, 219/25 Sukhumvit 21, Bangkok 10110. Tel: +66 259 1186. Fax: +66 260 0230 Internet: www.chuchawalroyalhaskoning.com Reference: T/0233 Water Resources Assessment for proposed Horticultural Farm Green and Clean Vegetables wanted to establish a new horticultural farm in Country: Muak Lek district, Saraburi. For their water resource they required a good- Saraburi, Thailand quality and reliable water supply. -

1. Baseline Characterization of Tad Fa Watershed, Khon Kaen Province, Northeast Thailand

1. Baseline Characterization of Tad Fa Watershed, Khon Kaen Province, Northeast Thailand Somchai Tongpoonpol, Arun Pongkanchana, Pranee Seehaban, Suhas P Wani and TJ Rego Introduction Agriculture is the main occupation in Thailand and it plays an important role in the economic development of the country. Thailand is located in the tropical monsoon climate region where the amount of rainfall is high but shortage of water occurs even in rainy season. Only 20% of total agricultural area is under irrigation, with rest constituting rainfed area, which has relatively lower crop yields. High soil erosion and reduced soil productivity are some of the problems in the rainfed area. The northeastern part of Thailand occupies one-third of the whole country. The climate of the region is drier than that of other regions. Most of the soils in Northeast Thailand are infertile at present and liable to be further degraded. The empirical evidence shows that crop yields decreased over the years after the conversion of the area as agricultural land by deforestation. The soils have become infertile due to improper soil management. The soils are low in fertility and have low water-holding capacity (WHC), and soil erosion is a serious problem. The interventions by ICRISAT (International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics) project aim to address these problems in the rainfed areas of Northeast Thailand. The watershed area in Phu Pa Man district in Khon Kaen province has been selected as benchmark site to address the above problems and increase agricultural productivity through a sustainable manner by adopting integrated soil, water and nutrient management (SWNM) and integrated crop management options. -

List of AQ in Other Provinces Compiled by Department of Consular Affairs | for More Information, Please Visit Note : 1

List of AQ Provinces As of 5 July 2021 List of AQ in other Provinces Compiled by Department of Consular Affairs | For more information, please visit www.hsscovid.com Note : 1. Passengers arrived at Suvarnabhumi Airport/ Don Mueang International Airport can be quarantined in AQ located in Chonburi and Prachinburi. 2. Passengers arrived at Phuket International Airport can be quarantined in AQ located in Phuket and Phang-nga. 3. For travellers entering Thailand via Ban Klong Luek (Aranyaprathet) Border Checkpoint can be quarantined in AQ located in Prachinburi. 4. For travellers entering Thailand via 2nd Thai–Lao Friendship Bridge can be quarantined in AQ located in Mukdahan. How to make a reservation? - Contact a hotel directly for reservation - Make a reservation on authorized online platforms (1) https://entrythailand.go.th/ (2) https://asqthailand.com/ (3) https://asq.locanation.com/ (4) https://asq.ascendtravel.com/ (5) https://www.agoda.com/quarantineth Starting Price (per person) for Thais Price range (Baht) No. Hotel Name Partnered Hospital Total Room (with discount on RT-PCR-test) per person Chonburi 1 Best Bella Pattaya Hotel Banglamung Hospital 39,000 – 45,000 90 Family Packages are available. 2 Avani Pattaya Resort Bangkok Hospital Pattaya 71,000 – 105,000 232 Family Packages are available. 3 Hotel J Residence Vibharam Laemchabang 39,000 – 60,000 75 Hospital Family Packages are available. 4 Tropicana Pattaya Memorial Hospital 37,000 - 56,000 170 5 Grand Bella Hotel Banglamung Hospital 27,000 - 44,000 344 6 Bella Express Hotel Banglamung Hospital 26,000 166 7 Sunshine Garden Resort Vibharam Laemchabang 37,500 - 48,750 65 Hospital 8 The Green Park Resort Vibharam Laemchabang 39,750 - 48,750 113 Hospital 9 Ravindra Beach Resort and Spa Bangkok Hospital Pattaya 69,000 - 72,000 100 Family Packages are available. -

The Mineral Industry of Thailand in 2013

2013 Minerals Yearbook THAILAND U.S. Department of the Interior November 2016 U.S. Geological Survey THE MINERAL INDUSTRY OF THAILAND By Yolanda Fong-Sam Thailand is one of the world’s leading producers of cement, production of phosphate rock decreased by 82% to 350 t in 2013 feldspar, gypsum, and tin metal. The country’s identified mineral from 1,990 t in 2012; perlite, by 65.5%; and refined copper, resources were being produced for domestic consumption by 58%. Other decreases were registered for tin ore (34%), and export. Thailand’s mines produced gold, iron ore, lead, antimony metal (27%), zinc (24%), and salt (5%). Data on manganese, silver, tungsten, and zinc. In addition, Thailand mineral production are in table 1. produced a variety of industrial minerals, such as cement, clays, Table 2 is a list of major mineral industry facilities. salt, sand, and stone (table 1; Crangle, 2015; Tanner, 2015; Tolcin, 2015; van Oss, 2015; U.S. Central Intelligence Agency, References Cited 2015). Asian Development Bank, 2014, Basic statistics 2014, Thailand: Asian In 2013, Thailand’s real rate of growth of the gross domestic Development Bank, 6 p. (Accessed January 15, 2013, at http://www.adb.org/ product (GDP) increased by 2.9% compared with 6.5% in 2012. sites/default/files/publication/42007/basic-statistics-2014.pdf.) The GDP based on purchasing power parity was about Crangle, R.D., Jr., 2015, Gypsum: U.S. Geological Survey Mineral Commodity Summaries 2015, p. 70–71. $980 billion, and the average inflation rate was 2.2% (Asian Tanner, A.O., 2015, Feldspar: U.S. -

Thailand HIT Case Study

Thailand HIT Case Study center for health and aging Thongchai Thavichachart, CEO, Thailand Health Information Technology and Policy Lab Center of Excellence for Life Sciences Narong Kasitipradith, President, Thai Medical Informatics Association Summary For over twenty years, both public and private hospitals have been trying to take advantage of the benefits of IT to improve health services in Thailand, yet varying resources and requirements of each institution have made for scattered, unharmonious HIT development throughout the country. The Ministry of Public Health made several attempts over the last ten years to develop a nationwide electronic medical record. However, hospitals responded unenthusiastically to the lack of immediate incentives and perceived benefits for each institution in exchange for the investment that building a common system for data sharing would require. Nevertheless, in 2007 an EMR exchange network remains in development, with the 21st century attempt likely to bring about new success in this area. HIT Adoption At present all 82 government provincial and large private hospitals in Thailand use some form of IT internally to manage drug dispensing, receipts, outpatient card searching, and appointment booking. The electronic medical record exchange system initiative in Thailand currently involves a few public and private institutions with a clear goal of supporting the medical tourism industry. This small but advanced partnership will act as the pilot project to help develop a model for wider coverage and a more comprehensive, farther-reaching system in the future. Hospitals share this information externally through hard copies, such as claims for health insurance. Most hospitals have unique software programs that are designed specifically for their internal use and operate quite comfortably within each institution’s legacy IT systems. -

CV Borwornsom Leerapan 2018.3

Curriculum Vitae Borwornsom Leerapan Department of Community Medicine Phone: +662-201-1518 (Ext.115) Faculty of Medicine Ramathibodi Hospital Fax: +662-201-1518 (Ext.134) Mahidol Universtiy Mobile: +6686-359-3330 270 Rama VI Road, Toong Phayathai E-mail: [email protected] Ratchathewi, Bangkok, Thailand 10400 E-mail: [email protected] EDUCATION Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D.) in Health Services Research, Policy and Administration University of Minnesota, School of Public Health, Minneapolis, MN, USA 2007-2011 • Howard Johnson Scholarship, 2007-2009, Joseph M. Juran Fellowship Award 2010, and Faculty of Medicine Ramathibodi Hospital Scholarship 2007-2011. Master of Science (S.M.) in Health Policy and Management 2004-2006 Harvard University, Graduate School of Public Health, Boston, MA, USA • Faculty of Medicine Ramathibodi Hospital Scholarship, 2004-2006. Doctor of Medicine (M.D.) 1993-1999 Mahidol University, Faculty of Medicine Siriraj Hospital, Bangkok, Thailand • Graduated with second-class honors. • Asian House Himeji Scholarship, 1999. POST-DOCTORAL TRAINING • Global Health Course, University of Minnesota’s Department of Medicine in collaboration with the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 2011-2012. • Fellowship in Health Care Management, Harvard University Health Services, 2006-2007. LICENSURES AND CERTIFICATIONS • Certificate in Travel Health™ (CTH®), the International Society of Travel Medicine (ISTM), 2011-present. • Diploma Thai Board of Preventive Medicine (Epidemiology), the Medical Council of Thailand, 2014-present. • Diploma Thai Board of Preventive Medicine (Public Health,), the Medical Council of Thailand, 2004-present. • Thai Medical Practice License, the Medical Council of Thailand, 1999-present. HONORS AND AWARDS • The Songseum Pundit Scholarship, awarded by Anandamahidol Foundataion Under the Royal Patronage of His Majesty the King of Thailand, 2013-2016. -

List of ASQ (Alternative State Quarantine) Compiled by Department of Consular Affairs | for More Information, Please Visit Note : 1

As of 23 February 2021 List of ASQ (Alternative State Quarantine) Compiled by Department of Consular Affairs | For more information, please visit www.hsscovid.com Note : 1. Passengers arrived at Suvarnabhumi Airport/ Don Mueang International Airport can be quarantined in ASQ and ALQ located in Chonburi and Prachinburi. 2. Passengers arrived at Phuket International Airport can be quarantined in ALQ located in Phuket and Phang-nga. 3. For travellers entering Thailand via Ban Klong Luek (Aranyaprathet) Border Checkpoint can be quarantined in ALQ located in Prachinburi. 4. For travellers entering Thailand via 2nd Thai–Lao Friendship Bridge can be quarantined in ALQ located in Mukdahan. How to make a reservation? - Contact a hotel directly for reservation - Make a reservation on authorized online platforms (1) https://www.agoda.com/quarantineth (2) https://asq.locanation.com/ (3) https://asq.ascendtravel.com/ Price range (Baht) Total No Name Partnered Hospital /person per 14-16 days Room 1 Movenpick BDMS Wellness Resort Bangkok Hospital 64,000 – 220,000 280 2 Qiu Hotel Sukumvit Hospital 32,000 – 35,000 105 3 The Idle Residence Samitivej Hospital 50,000 – 60,000 125 4 Grand Richmond Hotel World Medical Hospital (WMC) 45,000 - 90,000 300 5 Royal Benja Hotel Sukumvit Hospital 37,000 - 39,000 247 6 Anantara Siam Bangkok BPK 9 International Hospital 75,000 – 309,000 218 7 Grande Centerpoint Hotel Sukumvit Hospital 62,000 – 73,000 364 Sukhumvit 55 Family Packages are available. 8 AMARA Hotel Sukumvit Hospital 48,000 – 105,000 117 9 The Kinn Bangkok hotel Vibharam Hospital 30,000 – 50,000 61 Family Packages are available.