Seals DR. Edward F. Adolph Distinguished Lecture: the Remarkable Anti-Aging Effects of Aerobic Exercise On

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Circulatory System

Lec. 3 General Histology Instructor: Assist. Prof. Rasha A. Azeez The circulatory system The circulatory system provides a means of conveying nutrients and oxygen to and wastes out of the internal cells that make-up our bodies. There are two major components of the circulatory system. A. The cardiovascular system 1. Arteries, 2. Arterioles, 3. Capillaries, 4. Veins 5.Venules 6. Heart. B. The lymph vascular system 1. Blind ended lymphatic capillaries that collect lymph fluid from tissues. 2. Larger lymphatic vessels that connect with one and other and finally empty collected lymph into large veins in the neck where the lymphatic and cardiovascular systems merge. The cardiovascular system 1. Arterial system: There are three main types of arteries: o Elastic arteries o Muscular arteries o Arterioles o Elastic arteries These arteries that receive blood directly from the heart; includes the Aorta and the pulmonary artery; they need to be elastic because when the heart contracts, and ejects blood into these arteries, the walls need to stretch to accommodate the blood surge. The walls of these arteries have lots of elastin. a- Tunica intima is made up of an epithelium, which is a single layer of flattened epithelial cells, together with a supporting layer of elastin rich collagen. This layer also has fibroblasts and 'myointimal cells' that accumulate lipid with ageing, and the intima layer thickens, one of the first signs of atherosclerosis. a- Tunica media is broad and elastic with concentric fenestrated sheets of elastin, and collagen and only relatively few smooth muscle fibers. b- Tunica adventitia - has small vasa vasorum "a network of small blood vessels is present in the adventitia" as the large arteries need their own blood supply. -

The Circulatory System

TheThe CirculatoryCirculatory SystemSystem Xue Hui DepartmentDepartment ofof HistologyHistology && EmbryologyEmbryology TheThe CirculatoryCirculatory SystemSystem Cardiovascular system (blood vascular system) Heart Artery Capillary Vein Lymphatic vascular system Lymphatic capillary Lymphatic vessel Lymphatic duct II GeneralGeneral structurestructure ofof thethe bloodblood vesselsvessels Tunica intima Tunica media Tunica adventitia Drawing of a medium-sized muscular artery, showing its layers. II GeneralGeneral structurestructure ofof thethe bloodblood vesselsvessels IIII ArteryArtery Large artery Medium-sized artery Small artery Arteriole II Artery LargeLarge arteryartery Structure Tunica intima Tunica media 40-70 layers of elastic lamina Smooth muscle cells, collagenous fibers Tunica adventitia Function Carry the blood from the heart to the middle arteries Tunica Tunica intima intima Tunica Tunica media media Tunica Tunica adventitia adventitia Transverse sections showing part of a large elastic artery showing a well developed tunica media containing several elastic laminas. II Artery MediumMedium--sizedsized arteryartery Structure Tunica intima: clear internal elastic membrane Tunica media: 10-40 layers of smooth muscle cells Tunica adventitia: external elastic membrane Function Regulate the distribution of the blood to various parts of the body Tunica Internal intima elastic membrane Tunica media External elastic membrane Tunica adventitia II Artery SmallSmall arteryartery Structure characteristic Diameter:0.3-1mm Tunica intima: clear -

Histological Study of the Elastic Artery, Muscular Artery, and Their Junction in Neonate Dog

Winter & Spring 2016, Volume 13, Number 1 Histological Study of the Elastic Artery, Muscular Artery, and Their Junction in Neonate Dog Fatemeh Ramezani Nowrozani1* 1. Department of Anatomical Sciences, School of Veterinary Medicine, Kazerun Branch, Islamic Azad Univercity, Kazerun, Iran. Citation: Ramezani Nowrozani F. Histological study of the elastic artery, muscular artery, and their junction in neonate dog. Anatomical Sciences. 2016; 13(1):33-38. Dr. Fatemeh Ramezani Nowrozani is the assistant professor of anatomy, histology and embryology in the department of anatomical science at Kazerun Branch, Islamic Azad Univercity, Kazerun, Iran. She was graduated with a DVM and PhD from the College of Veterinary Medicine at Shiraz University. Since 2008, she has advised DVM students at Kazerun Branch, Islamic Azad Univercity anatomy, histology and embryology. Article info: A B S T R A C T Received: 12 Jan. 2015 Accepted: 02 Oct. 2015 Introduction: We did this study because there were a few studies about aorto-branch junction. Available Online: 01 Jan 2016 Methods: Four light microscope and electron microscope study, the abdominal aorta, renal artery, and the adjoining right and left renal arteries were dissected out from 4 neonate dogs. Results: Based on the results, there is only one cell type in the tunica intima of endothelium in both arteries. In abdominal aorta, there were open connective tissue spaces, containing elastic fibers between the internal elastic membrane and endothelium. In renal artery, endothelial cells were attached directly to the internal elastic membrane. In the abdominal aorta tunica media, layers of smooth muscle cells alternating with elastic lamellae were observed, but in renal artery, the smooth muscle cells were close to each other and a small quantity of collagen and elastic fibers were found between them. -

Anatomy Review: Blood Vessel Structure & Function

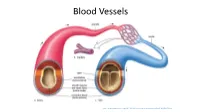

Anatomy Review: Blood Vessel Structure & Function Graphics are used with permission of: Pearson Education Inc., publishing as Benjamin Cummings (http://www.aw-bc.com) Page 1. Introduction • The blood vessels of the body form a closed delivery system that begins and ends at the heart. Page 2. Goals • To describe the general structure of blood vessel walls. • To compare and contrast the types of blood vessels. • To relate the blood pressure in the various parts of the vascular system to differences in blood vessel structure. Page 3. General Structure of Blood Vessel Walls • All blood vessels, except the very smallest, have three distinct layers or tunics. The tunics surround the central blood-containing space - the lumen. 1. Tunica Intima (Tunica Interna) - The innermost tunic. It is in intimate contact with the blood in the lumen. It includes the endothelium that lines the lumen of all vessels, forming a smooth, friction reducing lining. 2. Tunica Media - The middle layer. Consists mostly of circularly-arranged smooth muscle cells and sheets of elastin. The muscle cells contract and relax, whereas the elastin allows vessels to stretch and recoil. 3. Tunica Adventitia (Tunica Externa) - The outermost layer. Composed of loosely woven collagen fibers that protect the blood vessel and anchor it to surrounding structures. Page 4. Comparison of Arteries, Capillaries, and Veins • Let's compare and contrast the three types of blood vessels: arteries, capillaries, and veins. • Label the artery, capillary and vein. Also label the layers of each. • Arteries are vessels that transport blood away from the heart. Because they are exposed to the highest pressures of any vessels, they have the thickest tunica media. -

Blood and Lymph Vascular Systems

BLOOD AND LYMPH VASCULAR SYSTEMS BLOOD TRANSFUSIONS Objectives Functions of vessels Layers in vascular walls Classification of vessels Components of vascular walls Control of blood flow in microvasculature Variation in microvasculature Blood barriers Lymphatic system Introduction Multicellular Organisms Need 3 Mechanisms --------------------------------------------------------------- 1. Distribute oxygen, nutrients, and hormones CARDIOVASCULAR SYSTEM 2. Collect waste 3. Transport waste to excretory organs CARDIOVASCULAR SYSTEM Cardiovascular System Component function Heart - Produce blood pressure (systole) Elastic arteries - Conduct blood and maintain pressure during diastole Muscular arteries - Distribute blood, maintain pressure Arterioles - Peripheral resistance and distribute blood Capillaries - Exchange nutrients and waste Venules - Collect blood from capillaries (Edema) Veins - Transmit blood to large veins Reservoir Larger veins - receive lymph and return blood to Heart, blood reservoir Cardiovascular System Heart produces blood pressure (systole) ARTERIOLES – PERIPHERAL RESISTANCE Vessels are structurally adapted to physical and metabolic requirements. Vessels are structurally adapted to physical and metabolic requirements. Cardiovascular System Elastic arteries- conduct blood and maintain pressure during diastole Cardiovascular System Muscular Arteries - distribute blood, maintain pressure Arterioles - peripheral resistance and distribute blood Capillaries - exchange nutrients and waste Venules - collect blood from capillaries -

Diabetes, Cardiovascular Disease and the Microcirculation W

Strain and Paldánius Cardiovasc Diabetol (2018) 17:57 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12933-018-0703-2 Cardiovascular Diabetology REVIEW Open Access Diabetes, cardiovascular disease and the microcirculation W. David Strain1* and P. M. Paldánius2 Abstract Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the leading cause of mortality in people with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), yet a signifcant proportion of the disease burden cannot be accounted for by conventional cardiovascular risk factors. Hypertension occurs in majority of people with T2DM, which is substantially more frequent than would be antici- pated based on general population samples. The impact of hypertension is considerably higher in people with diabetes than it is in the general population, suggesting either an increased sensitivity to its efect or a confounding underlying aetiopathogenic mechanism of hypertension associated with CVD within diabetes. In this contribution, we aim to review the changes observed in the vascular tree in people with T2DM compared to the general population, the efects of established anti-diabetes drugs on microvascular outcomes, and explore the hypotheses to account for common causalities of the increased prevalence of CVD and hypertension in people with T2DM. Keywords: Microcirculation, Type 2 diabetes mellitus, Hypertension, Cardiovascular disease, Microvascular changes, Microalbuminuria Background in T2DM and hypertension, which in turn have signif- Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and hypertension cant implications with respect to future CV risk. are established risk factors for cardiovascular disease (CVD), and people with T2DM and hypertension have Vascular anatomy in cardiovascular disease an increased risk of cardiovascular (CV) mortality com- Although there is increasing evidence that the venous pared with those with either condition alone [1]. -

Microscopic Anatomy of the Human Vertebro-Basilar System

MICROSCOPIC ANATOMY OF THE HUMAN VERTEBRO-BASILAR SYSTEM RENATO P. CHOPARD * — GUILHERME DE ARAÚJO LUCAS * ADRIANA LAUDANA* SUMMARY — Concerning the structure of connective-muscular components the authors stu died the walls of the terminal segments of the vertebral arteries as well as the basilar artery, utilizing the following staining methods: Azan modified by Heideinheim, Weigert's resor-¬ cin-fuchsin, and Weigert modified by van Gieson. It was established that wall of the verte-¬ bro-basilar system exhibits a mixed structure, muscular and elastic, by means of which the vessels are adjusted to the specific blood circulation conditions. Thus, vertebral arteries show in the most external layer of tunica media an evident external elastic lamina. In contrast, in the basilar artery the elastic tissue is localized mainly in the tunica media, and is distributed heterogeneously. In its caudal segment the elastic fibers are situated in the most internal layer of tunica media, and in the cranial segment the elastic component is homogenously distributed in the whole of tunica media. Anatomia microscópica do sistema, vértebro basilar no homem. RESUMO — Os autores estudam a disposição dos componentes fibromusculare» da parede das artérias vertebrais em seus segmentos terminais e a artéria basilar, usando os seguintes métodos de coloração: Azan modificado por Heidenheim, resorcina-fucsina de Weigert e Weigert modificado por van Gieson. O sistema vértebro-basilar apresentou em sua parede estrutura mista, muscular e elástica, pela qual os vasos se adaptam às condições circulató rias especificas daquela região. Besta forma, ias artérias vertebrais apresentam na camada mais externa da túnica média uma lâmina elástica limitante externa evidente, ao contrário do encontrado na artéria basilar. -

Fetal Undernutrition Induces Resistance Artery Remodeling and Stiffness in Male and Female Rats Independent of Hypertension

biomedicines Article Fetal Undernutrition Induces Resistance Artery Remodeling and Stiffness in Male and Female Rats Independent of Hypertension 1,2, 2, 2,3 Perla Y. Gutiérrez-Arzapalo y , Pilar Rodríguez-Rodríguez y, David Ramiro-Cortijo , Marta Gil-Ortega 4 , Beatriz Somoza 4, Ángel Luis López de Pablo 2, Maria del Carmen González 2 and Silvia M. Arribas 2,* 1 Center of Research and Teaching in Health Sciences (CIDOCS), Universidad Autonoma de Sinaloa, Av. Cedros y calle Sauces s/n, Culiacán 80010, Sinaloa, Mexico; [email protected] 2 Department of Physiology, Faculty of Medicine, Universidad Autonoma de Madrid, C/Arzobispo Morcillo 2, 28029 Madrid, Spain; [email protected] (P.R.-R.); [email protected] (D.R.-C.); [email protected] (Á.L.L.d.P.); [email protected] (M.d.C.G.) 3 Department of Medicine, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Harvard Medical School, 330 Brookline Ave., Boston, MA 02215, USA 4 Department of Pharmaceutical and Health Sciences, Faculty of Pharmacy, Universidad CEU-San Pablo, C/Julián Romea, 23, 28003 Madrid, Spain; [email protected] (M.G.-O.); [email protected] (B.S.) * Correspondence: [email protected] These authors contributed equally to this study. y Received: 1 September 2020; Accepted: 14 October 2020; Published: 16 October 2020 Abstract: Fetal undernutrition programs hypertension and cardiovascular diseases, and resistance artery remodeling may be a contributing factor. We aimed to assess if fetal undernutrition induces resistance artery remodeling and the relationship with hypertension. Sprague–Dawley dams were fed ad libitum (Control) or with 50% of control intake between days 11 and 21 of gestation (maternal undernutrition, MUN). -

Developmental Adaptation of the Mouse Cardiovascular System to Elastin Haploinsufficiency

Developmental adaptation of the mouse cardiovascular system to elastin haploinsufficiency Gilles Faury, … , Barry Starcher, Robert P. Mecham J Clin Invest. 2003;112(9):1419-1428. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI19028. Article Cardiology Supravalvular aortic stenosis is an autosomal-dominant disease of elastin (Eln) insufficiency caused by loss-of-function mutations or gene deletion. Recently, we have modeled this disease in mice (Eln+/–) and found that Eln haploinsufficiency results in unexpected changes in cardiovascular hemodynamics and arterial wall structure. Eln+/– animals were found to be stably hypertensive from birth, with a mean arterial pressure 25–30 mmHg higher than their wild-type counterparts. The animals have only moderate cardiac hypertrophy and live a normal life span with no overt signs of degenerative vascular disease. Examination of arterial mechanical properties showed that the inner diameters of Eln+/– arteries were generally smaller than wild-type arteries at any given intravascular pressure. Because the Eln+/– mouse is hypertensive, however, the effective arterial working diameter is comparable to that of the normotensive wild-type animal. Physiological studies indicate a role for the renin-angiotensin system in maintaining the hypertensive state. The association of hypertension with elastin haploinsufficiency in humans and mice strongly suggests that elastin and other proteins of the elastic fiber should be considered as causal genes for essential hypertension. Find the latest version: https://jci.me/19028/pdf Developmental adaptation of the See the related Commentary beginning on page 1308. mouse cardiovascular system to elastin haploinsufficiency Gilles Faury,1 Mylène Pezet,1 Russell H. Knutsen,2 Walter A. Boyle,3 Scott P. -

Analysis of Blood Flow in One Dimensional Elastic Artery Using

Analysis of blood flow in one dimensional elastic artery using Navier-Stokes conservation laws Student: Crist´obalRodero G´omez1,3 Tutors: J. Alberto Conejero2 Ignacio Garc´ıa-Fern´andez3 1Facultat de Matem`atiques,Universitat de Val`encia arXiv:1710.06258v2 [physics.flu-dyn] 19 Oct 2017 2IUMPA, Universitat Polit`ecnicade Val`encia 3CoMMLab, Departament d’Inform`atica, Universitat de Val`encia i \Remember that all models are wrong; the practical question is how wrong do they have to be to not be useful." George Box, statistician. \Applied math pattern: In principle you could just ... but here's why that won't work in practice, and what you need to do instead." @AnalysisFact, tweet from Aug. 14th, 2017. Abstract In the last years, medical computer simulation has seen a great growth in several scientific branches, from modelling to numerical methods, going through computer science. The main goals of this incipient discipline are testing hypotheses before an intervention, or see what effect could have a drug in the system before actually taking it, among others. In this work we deduce from the most basic physical principles a one dimensional model for the simulation of blood flow in elastic arteries. We will provide some historical background, as well as a brief state of the art of these models. We will also study from a calculus point of view the equations of the model obtained, achieving an original result for the formation of shock waves in compliant vessels. Afterwards we will make some numerical simulations using Galerkin Discontinuous Finite Element Method. Since this is actually a family of methods, we will motivate and detail the elections and the implementation strategies. -

Blood Vessels

Elastic artery Venules. Muscular (distributing) Small veins (medium-sized) artery Medium- Arterioles sized veins Large veins General Structure of Blood Vessels - The wall of blood vessel is formed of three concentric layers: Tunica intima (interna) Tunica media Tunica adventitia (externa) Tunica Intima Single layer of flattened Subendothelial layer made Beneath the subendothelial endothelial cells (resting on up of loose connective layer is an internal elastic the basal lamina) lining the tissue. May have few lamina, composed of elastin lumen of the vessel longitudinally arranged (fenestrated elastic sheet), smooth muscle fibers separating the tunica intima from the tunica media Tunica Media Composed of smooth Large muscular arteries have external elastic lamina, muscles, some elastic fibers, separating the tunica media from the tunica adventitia. type III collagen (reticular Capillaries and postcapillary venules do not have a tunica fibers) and type I collagen. media, however, pericytes replace the tunica media. Tunica Adventitia - Composed of connective . Vasa vasorum: “Outermost layer” tissue containing types I & III NN..BB. collagen, fibroblasts and are small arterioles in tunica adventitia longitudinal elastic fibers and the outer part of tunica media. - Blends into the surrounding They are more prevalent in the connective tissue. walls of veins than arteries – why? Venous blood contains less oxygen and nutrients than arterial blood. ELASTIC ARTERIES T. Adventitia T. Intima T. Media Much thinner than T.M Fenestrated elastic loose C.T *Endothelium. membranes (sheets) (lamellae) In between, there are: 1. Smooth muscle cells: Subendothelial C.T. * less abundant & secrete Contains vasa all other components in T.M. vasorum → send 2. Collagen fibers (type I branches to the collagen). -

Circulation-Post

Blood Vessels http://www.majordifferences.com/2013/02/difference-between-artery-and-vein.html#.WiSD2VVKt0w ateries veins • Carry blood away from the • Carry blood toward the heart heart • Elastic arteries resist • Low pressure pressure and even it out • Thin walls (partially) • Large lumen • Muscular arteries maintain • Valves to prevent backflow & control pressure and promote flow of blood • Arterioles control blood in only one direction flow into capillaries capillaries – only endothelium http://anatomybody101.com/the-heart-is-made-of-what- muscle/the-heart-is-made-of-what-muscle-blood-vessels- tunica-intima-endothelium-subendothelial-layer-internal-or- external-elastic-membrane-tunica-media-externa-basement- membrane-artery-vein-capillary-bed/ muscular artery – vein – nerve elastin stain http://zoomify.lumc.edu/histonew/cardiovascular/dms108/popup.html Diagram of the tunics of an arterial wall (above): On the left, the drawing illustrates a typical stain and the tunica media smooth muscle are apparent; on the right, the same arterial wall has been stained with a special stain for elastin and you can see the elastin fibers running between the smooth muscle cells of the tunica media as well as through the loose connective tissue of the tunica externa. http://www.apsubiology.org/anatomy/2020/2020_Exam_Reviews/Exa m_1/CH19_Vessel_Wall_Histology.htm Elastic artery – stained for elastin https://casweb.ou.edu/p bell/Histology/Caption s/Cardiovascular/46.ela stic.art.10x.html Capillaries come in 3 varieties – most are “continuous” though http://ib.bioninja.com.au/standard-level/topic-6-human-physiology/62-the-blood-system/capillaries.html