Article Association of Age and CKD with Prognosis of Myocardial

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

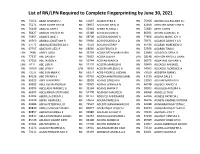

List of RN/LPN Required to Complete Fingerprinting by June 30, 2021

List of RN/LPN Required to Complete Fingerprinting by June 30, 2021 RN 74156 ABAD CHARLES U RN 61837 ACASIO KYRA K RN 75958 ADVINCULA ROLAND D J RN 75271 ABAD GLORY GAY M RN 59937 ACCOUSTI NEAL O RN 42910 ADZUARA MARY JANE R RN 76449 ABALOS JUDY S RN 52918 ACEBO RUSSELL J RN 72683 AETO JUSTIN RN 38427 ABALOS TRICIA H M RN 43188 ACEVEDO JUNE D RN 86091 AFONG CLAREN C D RN 70657 ABANES JANE J RN 68208 ACIDERA NORIVIE S RN 72856 AGACID MARIE JOY H RN 46560 ABANIA JONATHAN R RN 59880 ACIO ROSARIO A D RN 78671 AGANOS DAWN Y A V RN 67772 ABARQUEZ BLESSILDA C RN 72528 ACKLIN JUSTIN P RN 85438 AGARAN NOBEMEN O RN 67707 ABATAYO LIEZL P RN 68066 ACOB FERLITA D RN 52928 AGARAN TINA K LPN 7498 ABBEY LORI J RN 35794 ACOBA BETH MARY BARN RN 33999 AGASID GLISERIA D RN 77337 ABE DAVID K RN 73632 ACOBA JULIA R LPN 18148 AGATON KRYSTLE LIAAN RN 57015 ABE JAYSON K RN 53744 ACOPAN MARK N RN 66375 AGBAYANI REYNANTE LPN 6111 ABE LORI R RN 55133 ACOSTA MARISSA R RN 58450 AGCAOILI ANNABEL RN 18300 ABE LYNN Y LPN 18682 ACOSTA MYLEEN G A RN 54002 AGCAOILI FLORENCE A RN 73517 ABE SUN-HWA K RN 69274 ACRE-PICKRELL ALEXAN RN 79169 AGDEPPA MARK J RN 84126 ABE TIFFANY K RN 45793 ACZON-ARMSTRONG MARI RN 41739 AGENA DALE S RN 69525 ABEE JENNIFER E RN 19550 ADAMS CAROLYN L RN 33363 AGLIAM MARILYN A RN 69992 ABEE KEVIN ANDREW RN 73979 ADAMS JENNIFER N RN 46748 AGLIBOT NANCY A RN 69993 ABELLADA MARINEL G RN 39164 ADAMS MARIA V RN 38303 AGLUGUB AURORA A RN 66502 ABELLANIDA STEPHANIE RN 52798 ADAMSKI MAUREEN RN 68068 AGNELLO TAI D RN 83403 ABERILLA JEREMY J RN 84737 ADDUCCI -

JAPAN's COLONIAL EDUCATIONAL POLICY in KOREA by Hung Kyu

Japan's colonial educational policy in Korea, 1905-1930 Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Bang, Hung Kyu, 1929- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 03/10/2021 19:48:17 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/565261 JAPAN'S COLONIAL EDUCATIONAL POLICY IN KOREA 1905 - 1930 by Hung Kyu Bang A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 1 9 7 2 (c)COPYRIGHTED BY HONG KYU M I G 19?2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE I hereby recommend that this dissertation prepared under my direction by ___________ Hung Kvu Bang____________________________ entitled Japan's Colonial Educational Policy in Korea________ ____________________________________________________1905 - 1930_________________________________________________________________ be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement of the degree of ______________ Doctor of Philosophy_____________________ 7! • / /. Dissertation Director Date After inspection of the final copy of the dissertation, the following members of the Final Examination Committee concur in its approval and recommend its acceptance:* M. a- L L U 2 - iLF- (/) C/_L±P ^ . This approval and acceptance is contingent on the candidate's adequate performance and defense of this dissertation at the final oral examination. The inclusion of this sheet bound into the library copy of the dissertation is evidence of satisfactory performance at the final examination. -

Bab Ii “Menarikan Sang Liyan” : Feminisme Dalam Industri Musik

BAB II “MENARIKAN SANG LIYAN”i: FEMINISME DALAM INDUSTRI MUSIK “A feminist approach means taking nothing for granted because the things we take for granted are usually those that were constructed from the most powerful point of view in the culture ...” ~ Gayle Austin ~ Bab II akan menguraikan bagaimana perkembangan feminisme, khususnya dalam industri musik populer yang terepresentasikan oleh media massa. Bab ini mempertimbangkan kriteria historical situatedness untuk mencermati bagaimana feminisme merupakan sebuah realitas kultural yang terbentuk dari berbagai nilai sosial, politik, kultural, ekonomi, etnis, dan gender. Nilai-nilai tersebut dalam prosesnya menghadirkan sebuah realitas feminisme dan menjadikan realitas tersebut tak terpisahkan dengan sejarah yang telah membentuknya. Proses historis ini ikut andil dalam perjalanan feminisme from silence to performance, seperti yang diistilahkan Kroløkke dan Sørensen (2006). Perempuan berjalan dari dalam diam hingga akhirnya ia memiliki kesempatan untuk hadir dalam performa. Namun dalam perjalanan performa ini perempuan membawa serta diri “yang lain” (Liyan) yang telah melekat sejak masa lalu. Salah satu perwujudan performa sang Liyan ini adalah industri musik populer K-Pop yang diperankan oleh perempuan Timur yang secara kultural memiliki persoalan feminisme yang berbeda dengan perempuan Barat. 75 76 K-Pop merupakan perjalanan yang sangat panjang, yang mengisahkan kompleksitas perempuan dalam relasinya dengan musik dan media massa sebagai ruang performa, namun terjebak dalam ideologi kapitalisme. Feminisme diuraikan sebagai sebuah perjalanan “menarikan sang Liyan” (dancing othering), yang memperlihatkan bagaimana identitas the Other (Liyan) yang melekat dalam tubuh perempuan [Timur] ditarikan dalam beragam performa music video (MV) yang dapat dengan mudah diakses melalui situs YouTube. Tarian merupakan sebuah bentuk konsumsi musik dan praktik kultural yang membawa banyak makna tersembunyi mengenai konteks sosial (Wall, 2003:188). -

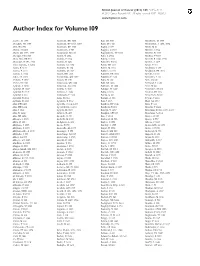

Author Index for Volume 109

British Journal of Cancer (2013) 109, 3133 – 3144 & 2013 Cancer Research UK All rights reserved 0007 – 0920/13 www.bjcancer.com Author Index for Volume 109 Aaseb, U 1467 Andersen, KK 3005 Bae, JM 1004 Benchetrit, M 1579 Abdallah, SO 1657 Andersen, RF 1243, 3067 Baek, JY 1420 Bendifallah, S 1498, 2774 Abel, GA 780 Anderson, KE 1908 Bagby, S 667 Benet, M 83 Abend, M 2286 Andersson, S 704 Baggott, C 2515 Benı´tez, J 2724 Abnet, CC 1367, 1997 Andonegui, MA 68 Bagnyukova, TV 1063 Bennett, K 1513 Aboagye, EO 2356 Andre, N 2024 Bahl, A 2554 Beohou, E 3057 Abou-Alfa, GK 915 Andre´s, E 2724 Bailey, S 2051 Berardi, R 1040, 1755 Absenger, G 395, 2316 Andre´s, R 1451 Baiocchi, G 184 Bercier, S 1437 Acha-Sagredo, A 2404 Andrew, AS 1954 Baird, DD 1291 Berge, Y 909 Adam, R 3126 Andrulis, IL 154 Baiter, M 2833 Bergkvist, L 257 Adams, E 2021 Andrulis, M 2665 Bakker, S 1093 Bergsland, EK 1725 Adenis, A 2574 Angell, HK 1618 Baldwin, DR 2058 Berndt, S 1352 Adjei, AA 1085 Annunziata, CM 1072 Baldwin, P 2533 Bernstein, L 761 Afchain, P 3057 Ansari, M 1271 Balic, M 589 Bert, AG 641 Afshar, M 1543 Antonescu, CR 2340 Ball, GR 1886 Bertrand, L 1586 Agaimy, A 2833 Antoniou, AC 1296 Ballester, M 1498 Betti, M 462 Agarwal, JP 2087 Anttila, A 2941 Balsdon, H 1549 Bettstetter, M 370 Agarwal, R 2515 Antunes, L 2646 Balta, S 3125 Beumer, JH 1725 Agarwal, S 872 Antunovic, P 2523 Bamia, C 332 Beuselinck, B 332 Agrawal, N 2051 Aoki, N 2155 Bamias, A 332 Beyene, J 2515 Agulnik, JS 2066 Aparicio, T 3057 Ban, J 2696 Bhat, GA 1367 Ahn, DH 1476 Apicella, C 154, 1296 Bandera, -

Implementasi Visual Son Gain Pada Outerwear

IMPLEMENTASI VISUAL SON GAIN PADA OUTERWEAR PENCIPTAAN Septina Kurniasri Lestari NIM 1610005222 PUBLIKASI KARYA ILMIAH TUGAS AKHIR PROGRAM STUDI S-1 KRIYA SENI JURUSAN KRIYA FAKULTAS SENI RUPA INSTITUT SENI INDONESIA YOGYAKARTA 2019 i UPT Perpustakaan ISI Yogyakarta UPT Perpustakaan ISI Yogyakarta IMPLEMENTASI VISUAL SON GAIN PADA OUTERWEAR Oleh: Septina Kurniasri Lestari INTISARI Sebagai penikmat musik pop Korea Selatan, karya Tugas Akhir ini mengambil Son Gain sebagai sumber ide penciptaannya. Son Gain merupakan salah satu penyanyi k-pop yang terkenal karena keunikannya. Konsep visual Son Gain bertema flower fairy dalam booklet albumnya yang berjudul End Again diimplementasikan menjadi motif utama yang menghiasi outerwear. Selain dapat memberikan perlindungaan pada tubuh, outerwear yang merupakan pakaian luar menjadikan ornamen berupa visual Son Gain yang diterapkan pada busana dapat terlihat secara utuh. Metode pendekatan yang digunakan dalam penciptaan karya ini adalah pendekatan estetis, pendekatan ergonomi dan clothing signals. Metode pengumpulan data dilakukan melalui studi pustaka dan observasi serta metode analisis data kualitatif. Metode penciptaan menggunakan practice-based research yaitu konsep penelitian berbasis praktik. Teknik perwujudan karya keseluruhannya menggunakan teknik tradisional batik tulis lorodan dengan proses colet dan tutup celup pada pewarnaannya. Sebagai teknik tambahan, sulam tangan digunakan untuk mempertegas motif utama berupa visual Son Gain pada busana. Serta proses jahit mesin untuk pengerjaan busananya. -

A Profile of Panhandling Black Bears in the Great Smoky Mountains

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 6-1983 A Profile of anhandlingP Black Bears in the Great Smoky Mountains National Park Jane Tate University of Tennessee - Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Part of the Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Commons Recommended Citation Tate, Jane, "A Profile of Panhandling Black Bears in the Great Smoky Mountains National Park. " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 1983. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/2526 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Jane Tate entitled "A Profile of Panhandling Black Bears in the Great Smoky Mountains National Park." I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in Ecology and Evolutionary Biology. Michael R. Pelton, Gordon M. Burghardt, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: Edward E. C. Clebsch, Cheryl B. Travis Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) To the Graduate Council: We are submitting herewith a dissertation written by Jane Tate entitled "A Profile of Panhandling Black Bears in the Great Smoky Mountains National Park." We have examined the final copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial ful fillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philo sophy, with a major in Ecology. -

A Comparative Analysis of the Level of Urban Resilience in the City Comprehensive Plan

The Sustainable City XII 517 A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF THE LEVEL OF URBAN RESILIENCE IN THE CITY COMPREHENSIVE PLAN KIM MIN-SEOK, YOU-MI JEON & JEA-SUN LEE Department of Urban Planning, Yonsei University, South Korea ABSTRACT In recent years, due to rapid changes in society, and climate change, cities have experienced difficulties in predicting various types of upcoming hazards and stresses. Uncertainties about the nature and extent of risks are increased especially when it comes to cities where interactions exist among various elements including human, society, economy, and culture. Considering limited prediction on inherent crises and difficulties in reaction plans, resilience strategy should be implemented prior to prevention strategy. The purpose of this study is to compare urban resilience levels of comprehensive plans for metropolitan areas with a population of over 1 million. Resilience measurements of capacity of resistance, adaptation, and recovery from external shocks and stresses will be applied to evaluate the level of urban resilience of cities in Korea. For the method of the study, it defined concepts of urban resilience through literature review, and derived indexes for urban resilience using preceding researches and case studies. Then, it developed detailed assessment indexes for evaluation of urban resilience level, and, finally, it evaluated and compared urban resilience level of comprehensive plans, using derived assessment indexes. As a result of the study, it suggested 56 assessment indexes and checklists in 8 sectors including land use plan, urban and residential environment, infrastructure, and more. The result of this study can be used as a base data for the future comprehensive plans when developing resilient cities. -

Joan E. Cho, Jae Seung Lee, and B.K. Song. 2017. “Media Exposure And

Journal of East Asian Studies (2017), page 1 of 22 doi:10.1017/jea.2016.41 Joan E. Cho, Jae Seung Lee and B.K. Song MEDIA EXPOSURE AND REGIME SUPPORT UNDER COMPETITIVE AUTHORITARIANISM: EVIDENCE FROM SOUTH KOREA Abstract This study explores whether and how exposure to mass media affects regime support in competitive authoritarian regimes. Using geographical and temporal variation in newspaper circulation and radio signal strength in South Korea under Park Chung Hee’s competitive authoritarian rule (1961–1972), we find that greater exposure to media was correlated with more opposition to the authoritarian incumbent, but only when the government’s control of the media was weaker. When state control of the media was stronger, the correlation between media exposure and regime support disappeared. Through a content analysis of newspaper articles, we also demonstrate that the regime’s tighter media control is indeed associated with pro-regime bias in news coverage. These findings from the South Korean case suggest that the liberalizing effect of mass media in competitive authoritarian regimes is conditional on the extent of government control over the media. Keywords competitive authoritarianism, media control, radio, newspaper, Korea, Park Chung Hee INTRODUCTION Studies on media development emphasize that the media can have a liberalizing effect on political systems by serving as a watchdog, but that state-controlled media props up authoritarian rule by functioning as a government mouthpiece. This study examines the relationship between media exposure and regime support in competitive authoritarian regimes where mass media is not continuously or entirely controlled but where the regime maintains the capability of exercising control. -

Appendix Ii Application and Supporting Materials for Authorization Under Clean Water Act 518 for Purposes of Administering Wate

APPENDIX II APPLICATION AND SUPPORTING MATERIALS FOR AUTHORIZATION UNDER CLEAN WATER ACT 518 FOR PURPOSES OF ADMINISTERING WATER QUALITY STANDARDS AND CERTIFICATION PROGRAMS UNDER §§ 303(c) and 401 Senec.a Nation of Indians Nt1T10/y ^ President - Todd Gates `Q► ^ Treasurer - Maurice A. John, Sr. Clerk - Lenith K. Waterman 12837 ROUTE 438 90 OHI:YO WAY CATTARAUGUS TERRITORY t% ALLEGANY TERRITORY SENECA NATION SENECA NATION IRVING, NY 14081 SALAMANCA, NY 14779 o o A ^ Q Tel. (716) 532-4900 ^ Tel. (716) 945-1790 FAX (716) 532-6272 of the •Wese k° FAX (716) 945-0150 PRESIDENT'S OFFICE March 28, 2018 Peter D. Lopez Regional Administrator U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Region 2 290 Broadway New York, NY 10007-1866 RE: Seneca Nation's Application for Recognition of Eligibility for CWA fi 106 Grant and for Authorization to Implement Water Quality Standards and Certification Programs Under CWA §§ 303 and 401 Dear Mr. Lopez: The Seneca Nation of Indians is applying to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency under Section 518(e) of the Clean Water Act, 33 U.S.C. § 1377(e), for eligibility to obtain a grant under CWA § 106, 33 U.S.C. § 1256, and to administer a water quality standards program pursuant to CWA § 303, 33 U.S.C. § 1313, and a water quality certification program under CWA § 401, 33 U.S.C. § 1341. The application and supporting documentation are included with this letter. Thank you in advance for your prompt attention to this matter. If you have any questions, please do not hesitate to contact Lisa Maybee, Director, Seneca Nation Environmental Protection Department, at 716-532-4900 ex. -

And Second-Generation Drug-Eluting Stents in Patients with ST-Segment

Journal of Clinical Medicine Article Comparison of First- and Second-Generation Drug-Eluting Stents in Patients with ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction Based on Pre-Percutaneous Coronary Intervention Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction Flow Grade Yong Hoon Kim 1,* , Ae-Young Her 1, Myung Ho Jeong 2, Byeong-Keuk Kim 3, Sung-Jin Hong 3, Seunghwan Kim 4 , Chul-Min Ahn 3, Jung-Sun Kim 3, Young-Guk Ko 3, Donghoon Choi 3, Myeong-Ki Hong 3 and Yangsoo Jang 3 1 Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Cardiology, Kangwon National University School of Medicine, 156 Baengnyeong Road, Chuncheon 24289, Korea; [email protected] 2 Cardiovascular Center, Department of Cardiology, Chonnam National University Hospital, Gwangju 61469, Korea; [email protected] 3 Division of Cardiology, Severance Cardiovascular Hospital, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul 03722, Korea; [email protected] (B.-K.K.); [email protected] (S.-J.H.); [email protected] (C.-M.A.); [email protected] (J.-S.K.); [email protected] (Y.-G.K.); [email protected] (D.C.); [email protected] (M.-K.H.); [email protected] (Y.J.) 4 Division of Cardiology, Inje University College of Medicine, Haeundae Paik Hospital, Busan 48108, Korea; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +82-33-258-9168 Citation: Kim, Y.H.; Her, A.-Y.; Jeong, Abstract: AbstractsThis study aims to investigate the two-year clinical outcomes between first- M.H.; Kim, B.-K.; Hong, S.-J.; Kim, S.; Ahn, C.-M.; Kim, J.-S.; Ko, Y.-G.; generation (1G) and second-generation (2G) drug-eluting stents (DES) based on pre-percutaneous Choi, D.; et al. -

Air Force's Personnel Center

AIR FORCE'S PERSONNEL CENTER 19E5 Staff Sergeant Worldwide Selects List Alphabetical by Last Name (*List excludes Intel, ISR, OSI AFSCs) For Public Release August 22, 2019 NAME AARDEMA JARED EUGE ABBAS ABBAS ABDULR ABBOTT DESHAWN MAR ABBOTT ZACHARY JOH ABBRUZZESE MICHAEL ABDULKAREEM RASHAD ABEL DAMON JEROME ABEL FRANCIS BRY ABEL MATTHEW BLAKE ABEL MATTHEW SCOTT ABELL TYLER THOMAS ABELL ZACHARY RYAN ABELRIVERA WILLIAM ABERNATHY JAMES A ABEYTA JAMIN MICHE ABEYTA TAYLOR KING ABITZ JOHN ISAAC ABLANG JEREMY GABR ABLES CASEY LYNNE ABNEY PHILLIP RYAN ABOAGYEWAA EUNICE ABRAHAM AARON MARK ABREGO ANDRES JULI ABRIL DANNYSON PAD ABSHIRE TRENT DEAN ACERO BRANDON MART ACEVEDO ARTHUR JR ACEVEDO BETANCOURT ACEVEDO DESIREE DA ACEVEDO RODRIGUEZ ACHUFF GABRIELLE D ACKERSON SABRINA L AIR FORCE'S PERSONNEL CENTER ACOSTA ARNIDA MARI ACOSTA CONSUELO CA ACOSTA JESSICA JOS ACOSTA JOSE ANTONI ACOSTA STACY ACRA JONATHAN WADI ACREE TREVOR WADE ACUESTA CHARLES VI ACUNA RAFAEL TRIAN ACUNA TELLEZ JESUS ADAM PEREZ JAICEL ADAME MIGUEL ADAMS AQUILAS DOS ADAMS BLAKE SPENCE ADAMS CALUM ALEXAN ADAMS CARTER AMBER ADAMS CHYEANNE LEI ADAMS CONNER AUSTI ADAMS EBONY NICOLE ADAMS JARED ANDREW ADAMS JARED CADEL ADAMS JEREMY JAMES ADAMS JOSHUA JAMES ADAMS KALA ALEXAND ADAMS KELSEY REED ADAMS KHADIJAH AMI ADAMS KYLE D ADAMS LOGAN WAYNE ADAMS NICHOLAS BRA ADAMS PETER DAVID ADAMS PHILLIP ANDR ADAMS TIMOTHY JOSH ADAMS TODD ALAKAI ADANSI PIPIM KOFI ADCOCK ERNEST JACO ADCOCK KARISA LYNN ADCOCK MATTHEW JOS ADDAE KEVIN KWADWO ADDERLEY SERGIO AL ADDERTONENRIGHT DA ADDISON JORDAN TYL AIR -

T-Tourgt).\SS 02Atlt36

HIGH TIDE: 4-1~-63 Lo.J4-14_68 TlDEI 5 l.J AT 171'2 o 5 AT 2336 6 3 AT 0'513 t-tOURGt).\SS 02ATlt36 SATURDAY, APRIL 13, 1968 VAT!CAN CITY (JPI }--"LONG LI'IE ~IAO" INSCRIPTIONS APPEARCI) IN ST Eastertide Brings Peace PETER'S SQUARE "'''10 ON THE WALLS Air Raiders, Artillery Lash Out or ROM ... N BASILICAS lAST NIGIIT POLICE BLAMED THE INSCI>IPTIONS To Riot· Wracked Cities ON PRO-CHINES[ STUDENTS IIHO TR.[D At Reds at Khe Sanh, Delta NEW YORK (UPI ) __ N"tIONII.L GUII.RO 1ROOf'S ;jEIIE TO IIHEARllP1' FopE P"IlL. Ifl's \I",y SAI"DN (UPI) •. _A ~,EIlIES Of HEAVY AMERIC.N .IR STRIKES .'10 ARTILLERY BA.RRAG[S WI THDRA""N fROM THE ~TREET~ Of CHI CAGO TODAY Of THE CROSS" PROCESSION A1' Hit TODAY KILLED :nS NORTH V,ETNAM[SE AND VIET CONG .ROUNO KHE SANN AND .N THE MEK_ A';, W(RE ALL BUT A fEW Of THE 13,000 Gis ON COLOSSEUM 'l'ESTERDAY AfTER THE DELT'" AREA, TH( US COMM_NO REPORTED DUTY IN '~ASllINC.T0N R",CIAL C"'tM PREVAILEO SI'IODTING OF BERLIN STUDENT LE ... OER AT KI<E SANH, AU S AIR rORCE C130 TRANSPORT PL.NE EXPLODED IN rLAMES TODAY AS OVER MOST Of THE UNI HO STATES ANO AUTHOR Rl!DI DUTSCHI{E POLICE QUICKLY W.S TOUCHING DOWN TO F"ICK UP A B.TTALION Of THE U 51ST CAVALRY DIVISION ITIES WERt HOPEfUL THAT (ASHR WOULD BRING DISPERSED THE YOUl'H5 BEfORE TI'IEY T>lE Gis CPOWOING ALONG THE ..