The Meaning of Sexual and Gender Identities in Transgender Men

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Resiliency Factors Among Transgender People of Color Maureen Grace White University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee University of Wisconsin Milwaukee UWM Digital Commons Theses and Dissertations May 2013 Resiliency Factors Among Transgender People of Color Maureen Grace White University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uwm.edu/etd Part of the Cognitive Psychology Commons, and the Educational Psychology Commons Recommended Citation White, Maureen Grace, "Resiliency Factors Among Transgender People of Color" (2013). Theses and Dissertations. 182. https://dc.uwm.edu/etd/182 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by UWM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UWM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RESILIENCY FACTORS AMONG TRANSGENDER PEOPLE OF COLOR by Maureen G. White A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Educational Psychology at The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee May 2013 ABSTRACT RESILIENCY FACTORS AMONG TRANSGENDER PEOPLE OF COLOR by Maureen G. White The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 2013 Under the Supervision of Professor Dr. Shannon Chavez-Korell Much of the research on transgender individuals has been geared towards identifying risk factors including suicide, HIV, and poverty. Little to no research has been conducted on resiliency factors within the transgender community. The few research studies that have focused on transgender individuals have made little or no reference to transgender people of color. This study utilized the Consensual Qualitative Research (CQR) approach to examine resiliency factors among eleven transgender people of color. -

Opening the Door Transgender People National Center for Transgender Equality

opening the door the opening The National Center for Transgender Equality is a national social justice people transgender of inclusion the to organization devoted to ending discrimination and violence against transgender people through education and advocacy on national issues of importance to transgender people. www.nctequality.org opening the door NATIO to the inclusion of N transgender people AL GAY AL A GAY NATIO N N D The National Gay and Lesbian AL THE NINE KEYS TO MAKING LESBIAN, GAY, L Task Force Policy Institute ESBIA C BISEXUAL AND TRANSGENDER ORGANIZATIONS is a think tank dedicated to E N FULLY TRANSGENDER-INCLUSIVE research, policy analysis and TER N strategy development to advance T ASK FORCE F greater understanding and OR equality for lesbian, gay, bisexual T and transgender people. RA N by Lisa Mottet S G POLICY E and Justin Tanis N DER www.theTaskForce.org IN E QUALITY STITUTE NATIONAL GAY AND LESBIAN TASK FORCE POLICY INSTITUTE NATIONAL CENTER FOR TRANSGENDER EQUALITY this page intentionally left blank opening the door to the inclusion of transgender people THE NINE KEYS TO MAKING LESBIAN, GAY, BISEXUAL AND TRANSGENDER ORGANIZATIONS FULLY TRANSGENDER-INCLUSIVE by Lisa Mottet and Justin Tanis NATIONAL GAY AND LESBIAN TASK FORCE POLICY INSTITUTE National CENTER FOR TRANSGENDER EQUALITY OPENING THE DOOR The National Gay and Lesbian Task Force Policy Institute is a think tank dedicated to research, policy analysis and strategy development to advance greater understanding and equality for lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender -

Analysing Prostitution Through Dissident Sexualities in Brazil

Contexto Internacional vol. 40(3) Sep/Dec 2018 http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0102-8529.2018400300006 Queering the Debate: Analysing Prostitution Through Dissident Pereira & Freitas Sexualities in Brazil Amanda Álvares Ferreira* Abstract: The aim of this article is to contrast prominent discourses on prostitution and human trafficking to the context of prostitution in Brazil and local feminist discourses on this matter, un- derstanding their contradictions and limitations. I look at Brazilian transgender prostitutes’ experi- ences to address an agency-related question that underlies feminist theorizations of prostitution: can prostitution be freely chosen? Is it necessarily exploitative? My argument is that discourses on sex work, departing from sex trafficking debates, are heavily engaged in a heteronormative logic that might be unable to approach the complexity and ambiguity of experiences of transgender prostitutes and, therefore, cannot theorize their possibilities of agency. To do so, I will conduct a critique of the naturalization of gender norms that hinders an understanding of experiences that exceed the binary ‘prostitute versus victim.’ I argue how both an abolitionist as well as a legalising solution to the is- sues involved in the sex market, when relying on the state as the guarantor of rights to sex workers, cannot account for the complexities of a context such as the Brazilian one, in which specific concep- tions of citizenship permit violence against sexually and racially marked groups to occur on such a large scale. Keywords: Gender; Prostitution; Sex Trafficking; Queer Theory; Feminism; Travestis. Introduction ‘Prostitution’ as an object of study can be approached through different perspectives that try to pin down exactly what are the social and political problems involved in it, and therefore how it can be dealt with by the State. -

Homophobia and Transphobia Illumination Project Curriculum

Homophobia and Transphobia Illumination Project Curriculum Andrew S. Forshee, Ph.D., Early Education & Family Studies Portland Community College Portland, Oregon INTRODUCTION Homophobia and transphobia are complicated topics that touch on core identity issues. Most people tend to conflate sexual orientation with gender identity, thus confusing two social distinctions. Understanding the differences between these concepts provides an opportunity to build personal knowledge, enhance skills in allyship, and effect positive social change. GROUND RULES (1015 minutes) Materials: chart paper, markers, tape. Due to the nature of the topic area, it is essential to develop ground rules for each student to follow. Ask students to offer some rules for participation in the postperformance workshop (i.e., what would help them participate to their fullest). Attempt to obtain a group consensus before adopting them as the official “social contract” of the group. Useful guidelines include the following (Bonner Curriculum, 2009; Hardiman, Jackson, & Griffin, 2007): Respect each viewpoint, opinion, and experience. Use “I” statements – avoid speaking in generalities. The conversations in the class are confidential (do not share information outside of class). Set own boundaries for sharing. Share air time. Listen respectfully. No blaming or scapegoating. Focus on own learning. Reference to PCC Student Rights and Responsibilities: http://www.pcc.edu/about/policy/studentrights/studentrights.pdf DEFINING THE CONCEPTS (see Appendix A for specific exercise) An active “toolkit” of terminology helps support the ongoing dialogue, questioning, and understanding about issues of homophobia and transphobia. Clear definitions also provide a context and platform for discussion. Homophobia: a psychological term originally developed by Weinberg (1973) to define an irrational hatred, anxiety, and or fear of homosexuality. -

What Can Asexuality Offer Sociology? Insights from the 2017 Asexual Community Census

Suggested citation: Carroll, Megan. (2020). What can asexuality offer sociology? Insights from the 2017 Asexual Community Census. Manuscript submitted for publication, California State University, San Bernardino, California. What Can Asexuality Offer Sociology? Insights from the 2017 Asexual Community Census Megan Carroll, Ph.D. Assistant Professor of Sociology California State University - San Bernardino Contact: Megan Carroll, Department of Sociology, California State University – San Bernardino, 5500 University Parkway SB327, San Bernardino, CA 92407-2397, [email protected] 2 *** In August 2018, the ASA Section on Sociology of Sexualities hosted a preconference before the annual meeting of the American Sociological Association to gather insights and showcase the work of top contributors of sociological work on sexualities. Outstanding work from across the discipline was featured in panels, workshops, and roundtables across the two days of conferencing, and critical questions of race, politics, and violence were deservedly prioritized amid an increasingly urgent political climate. While this preconference served to advance the discipline’s efforts toward generating knowledge and healing social divides, it also symbolized the range of American sociology’s contributions to interdisciplinary knowledge on sexuality. Missing from the work presented at the pre-conference was any mention of asexualities. Sociological insights on asexuality (i.e. a lack of sexual attraction) have been very limited. While some sociologists have devoted attention toward asexualities in their work (e.g. Carrigan 2011; Cuthbert 2017; Dawson, Scott, and McDonnell 2018; Poston and Baumle 2010; Scherrer and Pfeffer 2017; Simula, Sumerau, and Miller 2019; Sumerau et al. 2018; Troia 2018; Vares 2018), the field more often contributes to the invisibility of asexuality than sheds light on it. -

Understanding Attraction, Behavior, and Identity in the Asexual Community

Rowan University Rowan Digital Works Theses and Dissertations 6-2-2020 Understanding attraction, behavior, and identity in the asexual community Corey Doremus Rowan University Follow this and additional works at: https://rdw.rowan.edu/etd Part of the Clinical Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Doremus, Corey, "Understanding attraction, behavior, and identity in the asexual community" (2020). Theses and Dissertations. 2801. https://rdw.rowan.edu/etd/2801 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Rowan Digital Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Rowan Digital Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. UNDERSTANDING ATTRACTION, BEHAVIOR, AND IDENTITY IN THE ASEXUAL COMMUNITY by Corey Doremus A Thesis Submitted to the Department of Psychology College of Science and Mathematics In partial fulfillment of the requirement For the degree of Master of Arts in Clinical Psychology at Rowan University May 13, 2020 Thesis Chair: Meredith Joppa, Ph.D. and DJ Angelone, Ph.D. © 2020 Corey Doremus Dedication This thesis is dedicated to my wife, whose tireless support and love can not adequately be put into words. Thank you for never doubting my ability, even when I did. Acknowledgments I’m unable to quantify my thanks for my incredible mentors Dr. Meredith Joppa and Dr. DJ Angelone. Without their guidance and patience there’s simply no way this thesis would exist. I am incredibly honored to have the opportunity to benefit from their continued support of my personal and professional growth. iv Abstract Corey Doremus UNDERSTANDING ATTRACTION, BEHAVIOR, AND IDENTITY IN THE ASEXUAL COMMUNITY 2019-2020 Meredith Joppa Ph.D. -

Female Same-Sex Sexuality from a Dynamical Systems Perspective: Sexual Desire, Motivation, and Behavior

Female Same-Sex Sexuality from a Dynamical Systems Perspective: Sexual Desire, Motivation, and Behavior Rachel H. Farr, Lisa M. Diamond & Steven M. Boker Archives of Sexual Behavior The Official Publication of the International Academy of Sex Research ISSN 0004-0002 Volume 43 Number 8 Arch Sex Behav (2014) 43:1477-1490 DOI 10.1007/s10508-014-0378-z 1 23 Your article is protected by copyright and all rights are held exclusively by Springer Science +Business Media New York. This e-offprint is for personal use only and shall not be self- archived in electronic repositories. If you wish to self-archive your article, please use the accepted manuscript version for posting on your own website. You may further deposit the accepted manuscript version in any repository, provided it is only made publicly available 12 months after official publication or later and provided acknowledgement is given to the original source of publication and a link is inserted to the published article on Springer's website. The link must be accompanied by the following text: "The final publication is available at link.springer.com”. 1 23 Author's personal copy Arch Sex Behav (2014) 43:1477–1490 DOI 10.1007/s10508-014-0378-z ORIGINAL PAPER Female Same-Sex Sexuality from a Dynamical Systems Perspective: Sexual Desire, Motivation, and Behavior Rachel H. Farr • Lisa M. Diamond • Steven M. Boker Received: 13 February 2013 / Revised: 21 February 2014 / Accepted: 14 April 2014 / Published online: 6 September 2014 Ó Springer Science+Business Media New York 2014 Abstract Fluidity in attractions and behaviors among same- Keywords Dynamical systems analysis Á sex attracted women has been well-documented, suggesting Female sexuality Á Sexual orientation Á Sexual attraction Á the appropriateness of dynamical systems modeling of these Sexual behavior phenomena over time. -

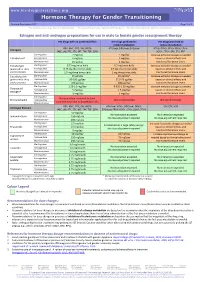

Hormone Therapy for Gender Transitioning Revised September 2017 Page 1 of 2 for Personal Use Only

www.hiv-druginteractions.org Hormone Therapy for Gender Transitioning Revised September 2017 Page 1 of 2 For personal use only. Not for distribution. For personal use only. Not for distribution. For personal use only. Not for distribution. Estrogen and anti-androgen preparations for use in male to female gender reassignment therapy HIV drugs with no predicted effect HIV drugs predicted to HIV drugs predicted to inhibit metabolism induce metabolism RPV, MVC, DTG, RAL, NRTIs ATV/cobi, DRV/cobi, EVG/cobi ATV/r, DRV/r, FPV/r, IDV/r, LPV/r, Estrogens (ABC, ddI, FTC, 3TC, d4T, TAF, TDF, ZDV) SQV/r, TPV/r, EFV, ETV, NVP Starting dose 2 mg/day 1 mg/day Increase estradiol dosage as needed Estradiol oral Average dose 4 mg/day 2 mg/day based on clinical effects and Maximum dose 8 mg/day 4 mg/day monitored hormone levels. Estradiol gel Starting dose 0.75 mg twice daily 0.5 mg twice daily Increase estradiol dosage as needed (preferred for >40 y Average dose 0.75 mg three times daily 0.5 mg three times daily based on clinical effects and and/or smokers) Maximum dose 1.5 mg three times daily 1 mg three times daily monitored hormone levels. Estradiol patch Starting dose 25 µg/day 25 µg/day* Increase estradiol dosage as needed (preferred for >40 y Average dose 50-100 µg/day 37.5-75 µg/day based on clinical effects and and/or smokers) Maximum dose 150 µg/day 100 µg/day monitored hormone levels. Starting dose 1.25-2.5 mg/day 0.625-1.25 mg/day Increase estradiol dosage as needed Conjugated Average dose 5 mg/day 2.5 mg/day based on clinical effects and estrogen† Maximum dose 10 mg/day 5 mg/day monitored hormone levels. -

Understanding Gender Stereotypes and Their Impact on Clients

University of Northern Iowa UNI ScholarWorks Graduate Research Papers Student Work 2008 Understanding gender stereotypes and their impact on clients Stacey Hurt University of Northern Iowa Copyright ©2008 Stacey Hurt Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uni.edu/grp Part of the Counseling Commons, Curriculum and Instruction Commons, and the Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy Recommended Citation Hurt, Stacey, "Understanding gender stereotypes and their impact on clients" (2008). Graduate Research Papers. 871. https://scholarworks.uni.edu/grp/871 This Open Access Graduate Research Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Work at UNI ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Research Papers by an authorized administrator of UNI ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Understanding gender stereotypes and their impact on clients Abstract Gender stereotyping has a complex and enduring history in our society, and it is an underlying factor in many issues – clients bring to counseling, including – among other things-women's and men's experience of depression (Nugent & Jones, 2005). A complicating aspect of gender stereotyping is that both males and females in our culture have been socially conditioned to fulfill many of the stereotypes imposed on them, and following stereotypical gender roles excessively can be harmful to their mental health, self- image, and interpersonal relationships (Nugent & Jones). Counselors can use gender-role analysis and other interventions to help clients gain insight into the gender role messages and stereotypes they have grown up with and challenge these messages (Corey, 2005). -

LGBTQ Notion Evaluation: a Bibliometric Analysis and Systematic Review

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Library Philosophy and Practice (e-journal) Libraries at University of Nebraska-Lincoln Summer 6-15-2021 LGBTQ Notion Evaluation: A Bibliometric Analysis and Systematic Review Poonam Gautam University School of Management, Kurukshetra University, Kurukshetra, HARYANA INDIA, [email protected] Dr. Ajay Solkhe University School of Management, Kurukshetra University, Kurukshetra, HARYANA INDIA, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac Part of the Business Administration, Management, and Operations Commons, Human Resources Management Commons, Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Studies Commons, Organizational Behavior and Theory Commons, and the Other Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons Gautam, Poonam and Solkhe, Dr. Ajay, "LGBTQ Notion Evaluation: A Bibliometric Analysis and Systematic Review" (2021). Library Philosophy and Practice (e-journal). 5886. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac/5886 1 LGBTQ Notion Evaluation: A Bibliometric Analysis and Systematic Review Poonam (Main Author) Junior Research Fellow University School of Management, Kurukshetra University, Kurukshetra-136118, Haryana, INDIA [email protected] Dr. Ajay Solkhe, (Corresponding Author) Sr. Assistant Professor University School of Management, Kurukshetra University, Kurukshetra-136118, Haryana, INDIA [email protected] Mobile: 9896544852 Abstract Several conservative sectors and employers are embracing equality objectives, including financial institutions, for example, more importantly, there has been a change in attitude and support towards the LGBT+ issues, which has been noticed in other professions and companies, including law and accountancy. The LGBT group includes Lesbians, Gay, Bisexuals and Transgender sexual orientation. Gay men and heterosexuals have also been observed to be in these groups. -

Media Reference Guide

media reference guide NINTH EDITION | AUGUST 2014 GLAAD MEDIA REFERENCE GUIDE / 1 GLAAD MEDIA CONTACTS National & Local News Media Sports Media [email protected] [email protected] Entertainment Media Religious Media [email protected] [email protected] Spanish-Language Media GLAAD Spokesperson Inquiries [email protected] [email protected] Transgender Media [email protected] glaad.org/mrg 2 / GLAAD MEDIA REFERENCE GUIDE TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION FAIR, ACCURATE & INCLUSIVE 4 GLOSSARY OF TERMS / LANGUAGE LESBIAN / GAY / BISEXUAL 5 TERMS TO AVOID 9 TRANSGENDER 12 AP & NEW YORK TIMES STYLE 21 IN FOCUS COVERING THE BISEXUAL COMMUNITY 25 COVERING THE TRANSGENDER COMMUNITY 27 MARRIAGE 32 LGBT PARENTING 36 RELIGION & FAITH 40 HATE CRIMES 42 COVERING CRIMES WHEN THE ACCUSED IS LGBT 45 HIV, AIDS & THE LGBT COMMUNITY 47 “EX-GAYS” & “CONVERSION THERAPY” 46 LGBT PEOPLE IN SPORTS 51 DIRECTORY OF COMMUNITY RESOURCES 54 GLAAD MEDIA REFERENCE GUIDE / 3 INTRODUCTION Fair, Accurate & Inclusive Fair, accurate and inclusive news media coverage has played an important role in expanding public awareness and understanding of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) lives. However, many reporters, editors and producers continue to face challenges covering these issues in a complex, often rhetorically charged, climate. Media coverage of LGBT people has become increasingly multi-dimensional, reflecting both the diversity of our community and the growing visibility of our families and our relationships. As a result, reporting that remains mired in simplistic, predictable “pro-gay”/”anti-gay” dualisms does a disservice to readers seeking information on the diversity of opinion and experience within our community. Misinformation and misconceptions about our lives can be corrected when journalists diligently research the facts and expose the myths (such as pernicious claims that gay people are more likely to sexually abuse children) that often are used against us. -

Women's Lived Experiences with Benevolent Sexism

Lesley University DigitalCommons@Lesley Graduate School of Arts and Social Sciences Counseling and Psychology Dissertations (GSASS) Spring 1-15-2021 WOMEN'S LIVED EXPERIENCES WITH BENEVOLENT SEXISM Sarah Schwerdel MA, LMHC Lesley University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lesley.edu/counseling_dissertations Part of the Counseling Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Schwerdel, Sarah MA, LMHC, "WOMEN'S LIVED EXPERIENCES WITH BENEVOLENT SEXISM" (2021). Counseling and Psychology Dissertations. 7. https://digitalcommons.lesley.edu/counseling_dissertations/7 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School of Arts and Social Sciences (GSASS) at DigitalCommons@Lesley. It has been accepted for inclusion in Counseling and Psychology Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Lesley. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. WOMEN’S LIVED EXPERIENCES WITH BENEVOLENT SEXISM A Dissertation submitted by Sarah A. Schwerdel In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Lesley University December 2020 © 2020 Sarah A. Schwerdel All rights reserved. WOMEN'S LIVED EXPERIENCES iii Dissertation Final Approval Form Division of Counseling and Psychology Lesley University This dissertation, titled: WOMEN’S LIVED EXPERIENCES WITH BENEVOLENT SEXISM as submitted for final approval by Sarah Schwerdel under the direction of the chair of the dissertation committee listed below. It was submitted to the Counseling and Psychology Division and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree at Lesley University. Approved: Sue L. Motulsky, Ed.D. Diana Direiter, Ph.D. Jo Ann Gammel, Ph.D. ______ Susan H.