The Seven Deadly Sins of Hieronymus Bosch

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Sides of the North

The Sides of the North The Sides of the North An Anthology in Honor of Professor Yona Pinson Edited by Tamar Cholcman and Assaf Pinkus The Sides of the North: An Anthology in Honor of Professor Yona Pinson Edited by Tamar Cholcman and Assaf Pinkus This book first published 2015 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2015 by Tamar Cholcman, Assaf Pinkus and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-7538-4 ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-7538-7 PROFESSOR YONA PINSON CONTENTS Editors’ Introduction .................................................................................. ix List of Publications by Professor Yona Pinson ........................................ xxi Chapter One ................................................................................................. 1 A New Bosch Epiphany? Adoration of the Magi Reassembled Larry Silver, University of Pennsylvania Chapter Two .............................................................................................. 20 From Flensburg to Constantinople: Cosmopolitanism and the Emblem in Melchior Lorck’s Self-Portraits Mara R. Wade, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign -

2-22- the Four Last Things

St. Mark Seeker’s Study Guide February 22, 2017: The Four Last Things – Death, Judgment, Heaven and Hell The Four Last Things, death, judgment, heaven and hell, are realities of human life. Although our end in this world is not the most attractive topic of conversation, Christians should understand that death is a passage to new life. The Communion of the Saints is the unity of baptized Christians with all who have gone before us in the oneness of God. As Christians, we don’t just prepare for death, but we live that new life today in the sanctifying grace of our God. As we consider the Four Last things, we should do so in the context of faith. Death The Christian Life and Death: The dying should be given attention and care to help them live their last moments in dignity and peace. Assisted suicide or euthanasia are not a morally responsible use of life. The dying should be accompanied and supported. No one ought to feel that they are a burden to others. Part of the challenge of the spiritual life is to both learn to love and to be loved. Why is it harder to be loved? Prayer for the Dying: The dying will be helped by the prayer of their relatives, who must see to it that the sick receive at the proper time the Sacraments that prepare them to meet the living God” (CCC, no. 2299). Death: The final article of the Creed proclaims our belief in everlasting life. At the Catholic Rite of Commendation of the Dying, sometimes prayed at the Anointing of the Sick, we sometimes hear this prayer: “Go forth, Christian soul, from this world... -

Part 1--The Remembrance of Death

Part 1--The Remembrance of Death Part 1--The Remembrance of Death A TREATISE (UNFINISHED) UPON THESE WORDS OF HOLY SCRIPTURE Memorare novissima, & in aeternum non peccabis “Remember the last things, & thou shalt never sin.”—Ecclus. 7 . Made about the year of our Lord 1522, by Sir Thomas More then knight, and one of the Privy Council of King Henry VIII, and also Under-Treasurer of England. If there were any question among men whether the words of holy Scripture or the doctrine of any secular author were of greater force and effect to the weal and profit of man’s soul (though we should let pass so many short and weighty words spoken by the mouth of our Saviour Christ Himself, to Whose heavenly wisdom the wit of none earthly creature can be comparable) yet this only text written by the wise man in the seventh chapter of Ecclesiasticus is such that it containeth more fruitful advice and counsel to the forming and framing of man’s manners in virtue and avoiding of sin, than many whole and great volumes of the best of old philosophers or any other that ever wrote in secular literature. Long would it be to take the best of their words and compare it with these words of holy Writ. Let us consider the fruit and profit of this in itself: which thing, well advised and pondered, shall well declare that of none whole volume of secular literature shall arise so very fruitful doctrine. For what would a man give for a sure medicine that were of such strength that it should all his life keep him from sickness, namely 1 if he might by the avoiding of sickness be sure to continue his life one hundred years? So is it now that these words giveth us all a sure medicine (if we forsloth 2 not the receiving) by which we shall keep from sickness, not the body, which none health may long keep from death (for die we must in few years, live we never so long), but the soul, which here preserved from the sickness of sin, shall after this eternally live in joy and be preserved from the deadly life of everlasting pain. -

Beginnings Lesson Plans

Outline of Lessons WEEK #1—Introduction to God’s Word Sunday Overview of Timeline Study What We Expect Wednesday “Who’s Who? and What’s What?” God, The Bible, Satan and Man WEEK #2—“In the Beginning” Sunday “Let Us”—God and Creation “Where Are You?”—Man Sins Wednesday Prophecy of Christ—God Makes Atonement Brothers: Cain, Abel and Seth WEEK #3—God’s Judgment and Mercy Sunday The Ark—God’s Design The Flood—God’s Judgment The Deliverance—God’s Mercy Wednesday The Rainbow—God’s Covenant Noah’s Three Sons—Shem, Ham and Japheth Tower of Babel—God Scatters the People 1 Essential Knowledge Lesson 1a 1. SW become familiar with the TIMELINE UNIT of study: • 12 TIMELINE sections • BIBLE HISTORY HIGHWAY • TIMELINE TALK 2. SW know how to use their TIMELINE booklet and what is inside. 3. SW learn something about their teachers. 4. SW know what their personal and spiritual responsibilities are in studying the BIBLE TIMELINE. Lesson 1b 1. God is the author of the Bible, and that the Bible is perfect. 2. Satan is real and is the author of sin. 3. Man is free to choose his master. Lesson 2a 1. God had Others with Him during creation. 2. God was pleased with His creation. 3. God is Great and man is small. 4. Man cannot hide from God. 5. Man must choose whom he will obey. Lesson 2b 1. Christ was in existence before man. 2. All who sin suffer consequences and sin separates man from God. 3. Some offerings to God are not respected by God. -

Amazing Facts Study Guide-02 Did God Create the Devil

Amazing Facts Study Guide 2 - Did God Create the Devil? Most people in the world are being deceived by an evil genius bent on destroying their lives - a brilliant mastermind called the devil, or Satan. But this dark prince is much more than what you might think... many say he's just a devious mythical figure, but the Bible says he's very real, and he's deceiving families, churches, and even nations to increase sorrow and pain. Here are the Bible's amazing facts about this prince of darkness and how you can overcome him! 1. With whom did sin originate? "The devil sinneth from the beginning." 1 John 3:8. "That old serpent, called the Devil, and Satan." Revelation 12:9. Answer: Satan, also called the devil, is the originator of sin. Without the Scriptures, the origin of evil would remain unexplained. 2. What was Satan's name before he sinned? Where was he living at that time? "How art thou fallen from heaven, O Lucifer, son of the morning!" Isaiah 14:12. Jesus said, "I beheld Satan as lightning fall from heaven." Luke 10:18. "Thou wast upon the holy mountain of God." Ezekiel 28:14. Answer: His name was Lucifer, and he was living in heaven. Lucifer is symbolized by the king of Babylon in Isaiah 14 and as the king of Tyrus in Ezekiel 28. 3. What was the origin of Lucifer? What responsible position did he hold? How does the Bible describe him? "Thou wast created." Ezekiel 28:13, 15. "Thou art the anointed cherub that covereth." Ezekiel 28:14. -

Transcendence of God

TRANSCENDENCE OF GOD A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF THE OLD TESTAMENT AND THE QUR’AN BY STEPHEN MYONGSU KIM A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE PHILOSOPHIAE DOCTOR (PhD) IN BIBLICAL AND RELIGIOUS STUDIES IN THE FACULTY OF HUMANITIES AT THE UNIVERSITY OF PRETORIA SUPERVISOR: PROF. DJ HUMAN CO-SUPERVISOR: PROF. PGJ MEIRING JUNE 2009 © University of Pretoria DEDICATION To my love, Miae our children Yein, Stephen, and David and the Peacemakers around the world. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First, I thank God for the opportunity and privilege to study the subject of divinity. Without acknowledging God’s grace, this study would be futile. I would like to thank my family for their outstanding tolerance of my late studies which takes away our family time. Without their support and kind endurance, I could not have completed this prolonged task. I am grateful to the staffs of University of Pretoria who have provided all the essential process of official matter. Without their kind help, my studies would have been difficult. Many thanks go to my fellow teachers in the Nairobi International School of Theology. I thank David and Sarah O’Brien for their painstaking proofreading of my thesis. Furthermore, I appreciate Dr Wayne Johnson and Dr Paul Mumo for their suggestions in my early stage of thesis writing. I also thank my students with whom I discussed and developed many insights of God’s relationship with mankind during the Hebrew Exegesis lectures. I also remember my former teachers from Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary, especially from the OT Department who have shaped my academic stand and inspired to pursue the subject of this thesis. -

The Moneylender and His Wife by Quentin Metsys (1466-1530) Oil on Panel 1514

The Moneylender and His Wife By Quentin Metsys (1466-1530) Oil on panel 1514 ABOUT THE ARTIST: Born in Louvain, Belgium in 1466, Quentin Metsys was trained as an ironsmith before becoming a painter and later settling in Antwerp, Belgium where in 1491 he is mentioned as a master in the guild of painters. At this time, Antwerp was the center of economic activity in the Low Countries which were comprised of Flanders (Northern Belgium) and the Netherlands. The growth and prosperity of Antwerp also attracted many artists who benefitted from the wealthy merchants who would collect and purchase their art. Metsys became Antwerp’s leading artist and founder of the Antwerp School. There is little known of Metsys’s artistic training but his style reflects the influence of multiple artists. “Matsys’ firmness of outline, clear modelling and thorough finish of detail stem from Van de Weyden's influence; from the Van Eycks and Memling by way of Dirck Bouts, the glowing richness of transparent pigments.” Other artists that have been referenced are Hieronymus Bosch, Albrecht Durer, Hans Holbein and Leonardo da Vinci. Not only is a religious influence felt in Metsys’s paintings, which was typical of traditional Flemish works, but he included a bit of satire as well. Metsys died in Antwerp in 1530. To mark the first centennial of his death there was a ceremony and a relief plaque with an additional inscription on the facade of the Antwerp Cathedral. Cornelius van der Geest, a patron, came up with the wording: "in his time a smith and afterwards a famous painter" honoring Metsys’ life. -

Jheronimus Bosch-His Sources

In the concluding review of his 1987 monograph on Jheronimus Bosch, Roger Marijnissen wrote: ‘In essays and studies on Bosch, too little attention has been paid to the people who Jheronimus Bosch: his Patrons and actually ordered paintings from him’. 1 And in L’ABCdaire de Jérôme Bosch , a French book published in 2001, the same author warned: ‘Ignoring the original destination and function his Public of a painting, one is bound to lose the right path. The function remains a basic element, and What we know and would like to know even the starting point of all research. In Bosch’s day, it was the main reason for a painting to exist’. 2 The third International Bosch Conference focuses precisely on this aspect, as we can read from the official announcement (’s-Hertogenbosch, September 2012): ‘New information Eric De Bruyn about the patrons of Bosch is of extraordinary importance, since such data will allow for a much better understanding of the original function of these paintings’. Gathering further information about the initial reception of Bosch’s works is indeed one of the urgent desiderata of Bosch research for the years to come. The objective of this introductory paper is to offer a state of affairs (up to September 2012) concerning the research on Bosch’s patronage and on the original function of his paintings. I will focus on those things that can be considered proven facts but I will also briefly mention what seem to be the most interesting hypotheses and signal a number of desiderata for future research. -

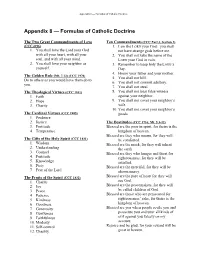

Appendix 8 — Formulas of Catholic Doctrine

Appendix 8 — Formulas of Catholic Doctrine Appendix 8 — Formulas of Catholic Doctrine The Two Great Commandments of Love Ten Commandments (CCC Part 3, Section 2) (CCC 2196) 1. I am the LORD your God: you shall 1. You shall love the Lord your God not have strange gods before me. with all your heart, with all your 2. You shall not take the name of the soul, and with all your mind. LORD your God in vain. 2. You shall love your neighbor as 3. Remember to keep holy the LORD’s yourself. Day. 4. Honor your father and your mother. The Golden Rule (Mt. 7:12) (CCC 1970) 5. You shall not kill. Do to others as you would have them do to 6. You shall not commit adultery. you. 7. You shall not steal. The Theological Virtues (CCC 1841) 8. You shall not bear false witness 1. Faith against your neighbor. 2. Hope 9. You shall not covet your neighbor’s 3. Charity wife. 10. You shall not covet your neighbor’s The Cardinal Virtues (CCC 1805) goods. 1. Prudence 2. Justice The Beatitudes (CCC 1716; Mt. 5:3-12) 3. Fortitude Blessed are the poor in spirit, for theirs is the 4. Temperance kingdom of heaven. Blessed are they who mourn, for they will The Gifts of the Holy Spirit (CCC 1831) be comforted. 1. Wisdom Blessed are the meek, for they will inherit 2. Understanding the earth. 3. Counsel Blessed are they who hunger and thirst for 4. Fortitude righteousness, for they will be 5. Knowledge satisfied. -

November 2012 Newsletter

historians of netherlandish art NEWSLETTER AND REVIEW OF BOOKS Dedicated to the Study of Netherlandish, German and Franco-Flemish Art and Architecture, 1350-1750 Vol. 29, No. 2 November 2012 Jan and/or Hubert van Eyck, The Three Marys at the Tomb, c. 1425-1435. Oil on panel. Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam. In the exhibition “De weg naar Van Eyck,” Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, October 13, 2012 – February 10, 2013. HNA Newsletter, Vol. 23, No. 2, November 2006 1 historians of netherlandish art 23 S. Adelaide Avenue, Highland Park, NJ 08904 Telephone: (732) 937-8394 E-Mail: [email protected] www.hnanews.org Historians of Netherlandish Art Offi cers President - Stephanie Dickey (2009–2013) Bader Chair in Northern Baroque Art Queen’s University Kingston ON K7L 3N6 Canada Vice-President - Amy Golahny (2009–2013) Lycoming College Williamsport, PA 17701 Treasurer - Rebecca Brienen University of Miami Art & Art History Department PO Box 248106 Coral Gables FL 33124-2618 European Treasurer and Liaison - Fiona Healy Seminarstrasse 7 D-55127 Mainz Germany Contents Board Members President's Message .............................................................. 1 Paul Crenshaw (2012-2016) HNA News ............................................................................1 Wayne Franits (2009-2013) Personalia ............................................................................... 2 Martha Hollander (2012-2016) Exhibitions ............................................................................ 3 Henry Luttikhuizen (2009 and 2010-2014) -

Pleasures of Gluttony Los Placeres De La Codicia Os Prazeres Da Gula

Pleasures of Gluttony Los placeres de la Codicia Os prazeres da Gula Burçin EROL 1 Abstract: In the late Middle Ages, especially in England, displaying an abundance of food and feasting became not only an act of pleasure but also a means of establishing status and wealth, despite gluttony being one of the seven deadly sins. In the fourteenth century – due to various reasons such as increased population, crop failure, the Black Death, and the disruption of food production by warfare – feasting, the displaying of food, and indulgence in gluttony was an indicator of wealth, riches, and high status for the upper class or the social climber as it is well indicated in the works of Chaucer and some of his contemporaries. Resumo: Especialmente na Idade Média Tardia, na Inglaterra, demonstrações de comida abundante e ceias se tornaram não somente um prazer, mas uma representação do estabelecimento de status e riqueza, apesar da gula ser proclamada um dos sete pecados capitais. No século XIV, devido a várias calamidades, como crescimento populacional, problemas na colheita , a peste negra e a quebra da produção de comida, o fornecimento e a ostentação de comida e indulgencia na gula foi um indicador de riqueza grande status para a classe alta ou para ascendentes sociais, como bem indicada nos trabalhos de Chaucer e alguns de seus contemporâneos. Keywords: Seven Deadly Sins – Gluttony – Pleasure – Middle English Literature. Palavras-chaves: Sete Pecados Capitais – Gula – Prazer – Literatura em Inglês Médio. 1 Prof. Dr., Department of English Language and Literature, Faculty of Letters, Hacettepe University, Ankara, Turkey. E-mail: [email protected] . -

Explaining the Evils of the Nephilim

Explaining The Nephilim Giants ‘When mankind began to multiply on the earth and daughters were born to them, the ‘sons of God’ (fallen angels) saw the daughters of men (human women) were beautiful and they took (raped) all the women they desired and chose. (As a result) there were Nephilim on the earth in those days and also afterwards when the ‘sons of God’ (fallen angels) lived with the daughters of mankind and they bore children to them. Those were the mighty men who were of old, men of renown’ (Genesis 6:1,2 & 4). ‘The people who dwell in the land are strong and the cities are fortified and very great. We saw the children (descendents) of Anak there … Amalek dwells in the land of the South … They brought up an evil report of the land they had spied out to the Children of Israel saying, “The land where we spied out is a land that eats up its inhabitants. All the people who we saw in it are men of great stature (giants). There we saw the Nephilim, the sons (descendents) of Anak who come of the Nephilim and we were in our own sight as grasshoppers and so we were in their sight’” (Numbers 13:28, 29, 32 & 33). These evil beings called the Nephilim were the wicked giant offspring born to the women who had been raped by the fallen angels referred to as ‘the sons of God’. The Nephilim ‘men of renown’ were not decent men who were well known, they were vicious, violent, wicked half human, half fallen angels who later brought into existence the Amalek and Anakim (plural of Anak).