Fall 2007 Flutist Quarterly

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Notre Dame Collegiate Jazz Festival Program, 1966

Archives of the University of Notre Dame Archives of the University of Notre Dame ~ ISND COLLEGIATE AM FM JAZZ 640 k. c. 88.9 m. c. Nocturne Mainstream .. FESTIVAL The Sound of Music, in this case ... Jazz, at Notre Dame MARCH L1.J~NC:>C~:E='~ Westinghouse Broadcasting 25 f 26 ORDER YOUR CJF RECORDS FROM: UNIVERSITY OF NOTRE Official Recordists for Mid-West Band Clinics DAME and many State and District Contests .. and Festivals ... JUDOES Don DeMicheal 11359 S. Lothair Ave. ,Chicago 43, illinois Quincy Jones Robert Share Phone: BEverly 3-4717 (Area Code 312) Charles Suber Billy Taylor .1 Archives of the University of Notre Dame Oft.Thought Whims & Fancies call, the shout, for that sudden, exciting, always recognizable cry: "HEY, LISTEN TO ME. I'VE Ere Judgement is Wrought GOT IT!". And for that moment he does ha~e it; and, for as many moments as his insides can sus WELCOME by Charles Suber, Mother Judge tain him, he has it. And he has me, Attention is The amenities have been satisfied. Coffee is happily given. I want to listen, pay heed and my sen'ed - it is still warm (and over-sweet). My respects. Judge looks to judge with smiles of TO pipe is lighted - more pleasurable for it's illegal shared appraisal. Not that it is time for points or comfort. The real judges (to my right) have been prizes. Just the acknowledgement that this young fed, provided with programs, adjudication sheets, musician is saying something important - here newly-pointed pencils (with erasers), and music and now. -

Liner Notes (PDF)

Debussy’s Traces Gaillard • Horszowski • Debussy Marik • Fourneau 1904 – 1983 Debussy’s Traces: Marius François Gaillard, CD II: Marik, Ranck, Horszowski, Garden, Debussy, Fourneau 1. Preludes, Book I: La Cathédrale engloutie 4:55 2. Preludes, Book I: Minstrels 1:57 CD I: 3. Preludes, Book II: La puerta del Vino 3:10 Marius-François Gaillard: 4. Preludes, Book II: Général Lavine 2:13 1. Valse Romantique 3:30 5. Preludes, Book II: Ondine 3:03 2. Arabesque no. 1 3:00 6. Preludes, Book II Homage à S. Pickwick, Esq. 2:39 3. Arabesque no. 2 2:34 7. Estampes: Pagodes 3:56 4. Ballade 5:20 8. Estampes: La soirée dans Grenade 4:49 5. Mazurka 2:52 Irén Marik: 6. Suite Bergamasque: Prélude 3:31 9. Preludes, Book I: Des pas sur la neige 3:10 7. Suite Bergamasque: Menuet 4:53 10. Preludes, Book II: Les fées sont d’exquises danseuses 8. Suite Bergamasque: Clair de lune 4:07 3:03 9. Pour le Piano: Prélude 3:47 Mieczysław Horszowski: Childrens Corner Suite: 10. Pour le Piano: Sarabande 5:08 11. Doctor Gradus ad Parnassum 2:48 11. Pour le Piano: Toccata 3:53 12. Jimbo’s lullaby 3:16 12. Masques 5:15 13 Serenade of the Doll 2:52 13. Estampes: Pagodes 3:49 14. The snow is dancing 3:01 14. Estampes: La soirée dans Grenade 3:53 15. The little Shepherd 2:16 15. Estampes: Jardins sous la pluie 3:27 16. Golliwog’s Cake walk 3:07 16. Images, Book I: Reflets dans l’eau 4:01 Mary Garden & Claude Debussy: Ariettes oubliées: 17. -

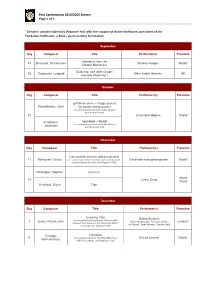

Past Commissions 2014/15

Past Commissions 2014/2015 Season Page 1 of 5 * Denotes commissioned by Wigmore Hall with the support of André Hoffmann, president of the Fondation Hoffmann, a Swiss grant-making foundation September Day Composer Title Performer(s) Première Variations from the 14 Birtwistle, Sir Harrison Nicolas Hodges World* Golden Mountains Study No. 44A after Chopin 15 Godowsky, Leopold Marc-André Hamelin UK nouvelle étude No.1 October Day Composer Title Performer(s) Première gefährlich dünn — fragile pieces Petraškevičs, Jānis for double string quartet (co-commissioned by Ensemble Modern and Wigmore Hall) 10 Ensemble Modern World* Schöllhorn, sous-bois – Sextet (co-commissioned by Ensemble Modern Johannes and Wigmore Hall) November Day Composer Title Performer(s) Première Carnaval for clarinet, piano and cello 11 Mantovani, Bruno (co-commissioned by Ensemble intercontemporain, Ensemble intercontemporain World* Opéra national de Paris and Wigmore Hall) Montague, Stephen nun-mul World 16 Jenna Sung World Pritchard, Gwyn Tide December Day Composer Title Performer(s) Première Uncanny Vale Britten Sinfonia (co-commissioned by Britten Sinfonia with 3 Jones, Patrick John (Emer McDonough, Nicholas Daniel, London* support from donors to the Musically Gifted Joy Farrall, Sarah Burnett, Stephen Bell) campaign and Wigmore Hall) Turnage, Contusion 6 (co-commissioned by The Radcliffe Trust, Belcea Quartet World* Mark-Anthony NMC Recordings and Wigmore Hall) Past Commissions 2014/2015 Season Page 2 of 5 January Day Composer Title Performer(s) Première Light and Matter Britten Sinfonia (co-commissioned by Britten Sinfonia with 14 Saariaho, Kaija (Jacqueline Shave, Caroline Dearnley, London* support from donors to the Musically Gifted campaign Huw Watkins) and Wigmore Hall) 3rd Quartet Holt, Simon (co-commissioned by The Radcliffe Trust, World* NMC Recordings, Heidelberger Frühling, and 19 Wigmore Hall) JACK Quartet Haas, Georg Friedrich String Quartet No. -

The Morning I Met LOUIS MOYSE, He Was at the Piano Playing A

NWCR888 Louis Moyse Works for Flute and Piano First Sonata (1975) ...................................................... (21:26) 1. I. Allegro ................................................. (5:14) 2. II. Poco adagio ......................................... (7:19) 3. III. Scherzo ............................................... (3:09) 4. IV. Allegro scherzando ............................. (5:14) Introduction, Theme and Variations (1982) ................ (19:34) 5. Introduction .............................................. (6:18) 6. Theme ....................................................... (1:23) 7. Variation I ................................................ (0:32) 8. Variation II ............................................... (1:59) 9. Variation III .............................................. (0:59) 10. Variation IV ............................................. (3:45) 11. Variation V ............................................... (0:59) 12. Variation VI ............................................. (1:18) 13. Variation VII ............................................ (2:10) Second Sonata (1998) .................................................. (25:57) 14. I. Allegro vivo ......................................... (7:07) 15. II. Poco adagio ......................................... (8:51) 16. III. Scherzo ............................................... (3:15) 17. IV. Presto ................................................. (6:40) Karen Kevra, flute; Paul Orgel, piano Total playing time: 66:20 Ê & © 2002 Composers Recordings, -

Sounding Nostalgia in Post-World War I Paris

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2019 Sounding Nostalgia In Post-World War I Paris Tristan Paré-Morin University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Recommended Citation Paré-Morin, Tristan, "Sounding Nostalgia In Post-World War I Paris" (2019). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 3399. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/3399 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/3399 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Sounding Nostalgia In Post-World War I Paris Abstract In the years that immediately followed the Armistice of November 11, 1918, Paris was at a turning point in its history: the aftermath of the Great War overlapped with the early stages of what is commonly perceived as a decade of rejuvenation. This transitional period was marked by tension between the preservation (and reconstruction) of a certain prewar heritage and the negation of that heritage through a series of social and cultural innovations. In this dissertation, I examine the intricate role that nostalgia played across various conflicting experiences of sound and music in the cultural institutions and popular media of the city of Paris during that transition to peace, around 1919-1920. I show how artists understood nostalgia as an affective concept and how they employed it as a creative resource that served multiple personal, social, cultural, and national functions. Rather than using the term “nostalgia” as a mere diagnosis of temporal longing, I revert to the capricious definitions of the early twentieth century in order to propose a notion of nostalgia as a set of interconnected forms of longing. -

London Mozart Players Wind Trio When He Left to Focus on His Freelance Career

Timothy Lines (Clarinet) Timothy studied at the Royal College of Music with Michael Collins and now enjoys a wide- ranging career as a clarinettist. He has played with all the major symphony orchestras in London as well as with chamber groups including London Sinfonietta and the Nash Ensemble. From 1999 to 2003 he was Principal Clarinet of the London Symphony Orchestra and was also chairman of the orchestra during his last year there. From September 2004 to January 2006 he was section leader clarinet of the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra, London Mozart Players Wind Trio when he left to focus on his freelance career. He plays on original instruments with the English Baroque Soloists, the Orchestre Revolutionnaire et Romantique and the Orchestra of Thursday 12th March 2020 at 7.30 pm the Age of Enlightenment and is also frequently engaged to record film music and pop music Cavendish Hall, Edensor tracks. Timothy is Professor of Clarinet at both the Royal College of Music and the Royal Academy of Music, and is the clarinet coach for the National Youth Orchestra of Great Britain. In March 2016 he was awarded a Fellowship of the Royal College of Music and was later that year invited to become Principal Clarinet of the London Mozart Players. Concert Champêtre H. TOMASI Gareth Hulse (Oboe) (1901-1971) After reading music at Cambridge, Gareth Hulse studied with Janet Craxton at the Royal Divertimento K439b W.A. MOZART Academy of Music, and with Heinz Holliger at the Freiburg Hochschule fur Musik. On his (1756-1791) return to England he was appointed Principal Oboe with the Northern Sinfonia, a position he has since held with English National Opera and the London Philharmonic. -

Women Pioneers of American Music Program

Mimi Stillman, Artistic Director Women Pioneers of American Music The Americas Project Top l to r: Marion Bauer, Amy Beach, Ruth Crawford Seeger / Bottom l to r: Jennifer Higdon, Andrea Clearfield Sunday, January 24, 2016 at 3:00pm Field Concert Hall Curtis Institute of Music 1726 Locust Street, Philadelphia Charles Abramovic Mimi Stillman Nathan Vickery Sarah Shafer We are grateful to the William Penn Foundation and the Musical Fund Society of Philadelphia for their support of The Americas Project. ProgramProgram:: WoWoWomenWo men Pioneers of American Music Dolce Suono Ensemble: Sarah Shafer, soprano – Mimi Stillman, flute Nathan Vickery, cello – Charles Abramovic, piano Prelude and Fugue, Op. 43, for Flute and Piano Marion Bauer (1882-1955) Stillman, Abramovic Prelude for Piano in B Minor, Op. 15, No. 5 Marion Bauer Abramovic Two Pieces for Flute, Cello, and Piano, Op. 90 Amy Beach (1867-1944) Pastorale Caprice Stillman, Vickery, Abramovic Songs Jennifer Higdon (1962) Morning opens Breaking Threaded To Home Falling Deeper Shafer, Abramovic Spirit Island: Variations on a Dream for Flute, Cello, and Piano Andrea Clearfield (1960) I – II Stillman, Vickery, Abramovic INTERMISSION Prelude for Piano #6 Ruth Crawford Seeger (1901-1953) Study in Mixed Accents Abramovic Animal Folk Songs for Children Ruth Crawford Seeger Little Bird – Frog He Went A-Courtin' – My Horses Ain't Hungry – I Bought Me a Cat Shafer, Abramovic Romance for Violin and Piano, Op. 23 (arr. Stillman) Amy Beach June, from Four Songs, Op. 53, No. 3, for Voice, Violin, and -

Mimi Stillman, Artistic Director

MIMI STILLMAN, ARTISTIC DIRECTOR 2017 2018 “ONE OF THE MOST DYNAMIC GROUPS IN THE US!” SEA—The Huffington SON Post DOLCE SUONO ENSEMBLE has been enriching and informing people’s lives through chamber music since its founding by flutist and Artistic Director Mimi Stillman in 2005. Hailed as an “adventurous ensemble” (The New York Times) and “One of the most dynamic groups in the US!” (The Huffington Post), the ensemble performs critically acclaimed chamber music concerts at home and on tour, commissions new works, makes recordings, and engages in community engagement partnerships. Dolce Suono Trio, its high-profile trio of flute, cello, and piano, evolved organically from the longstanding collaboration of flutist Mimi Stillman and pianist Charles Abramovic joined by cellist Nathan Vickery (Gabriel Cabezas) to explore and expand the repertoire of this captivating combination. “The three were flawlessly in sync – even their trills!” (The Philadelphia Inquirer) Dolce Suono Ensemble presents innovative programs of Baroque to new music. Historian Mimi Stillman’s curatorial vision sets the music in its broadest cultural context. Some of its artistically and intellectually powerful projects include the celebrated Mahler 100/ Schoenberg 60, Debussy in Our Midst: A Celebration of the 150th Anniversary of Claude Debussy, A Place and a Name: Remembering the Holocaust, Women Pioneers of American Music, and Música en tus Manos (Music in Your Hands), our engagement initiative with the Latino community. Dolce Suono Ensemble enjoys the support of grantors including the Nation- al Endowment for the Arts, William Penn Foundation, Knight Foundation, Pennsylvania Council on the Arts, and Yamaha Corporation of America. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Summer

SEMI OIAWA MUSIC DIRECTOR BERNARD HAITINK PRINCIPAL GUEST CONDUCTOR • i DALE CHIHULY INSTALLATIONS AND SCULPTURE / "^ik \ *t HOLSTEN GALLERIES CONTEMPORARY GLASS SCULPTURE ELM STREET, STOCKBRIDGE, MA 01262 . ( 41 3.298.3044 www. holstenga I leries * Save up to 70% off retail everyday! Allen-Edmoi. Nick Hilton C Baccarat Brooks Brothers msSPiSNEff3svS^:-A Coach ' 1 'Jv Cole-Haan v2^o im&. Crabtree & Evelyn OB^ Dansk Dockers Outlet by Designs Escada Garnet Hill Giorgio Armani .*, . >; General Store Godiva Chocolatier Hickey-Freeman/ "' ft & */ Bobby Jones '.-[ J. Crew At Historic Manch Johnston & Murphy Jones New York Levi's Outlet by Designs Manchester Lion's Share Bakery Maidenform Designer Outlets Mikasa Movado Visit us online at stervermo OshKosh B'Gosh Overland iMrt Peruvian Connection Polo/Ralph Lauren Seiko The Company Store Timberland Tumi/Kipling Versace Company Store Yves Delorme JUh** ! for Palais Royal Phone (800) 955 SHOP WS »'" A *Wtev : s-:s. 54 <M 5 "J* "^^SShfcjiy ORIGINS GAUCftV formerly TRIBAL ARTS GALLERY, NYC Ceremonial and modern sculpture for new and advanced collectors Open 7 Days 36 Main St. POB 905 413-298-0002 Stockbridge, MA 01262 Seiji Ozawa, Music Director Ray and Maria Stata Music Directorship Bernard Haitink, Principal Guest Conductor One Hundred and Twentieth Season, 2000-2001 SYMPHONY HALL CENTENNIAL SEASON Trustees of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Inc. Peter A. Brooke, Chairman Dr. Nicholas T. Zervas, President Julian Cohen, Vice-Chairman Harvey Chet Krentzman, Vice-Chairman Deborah B. Davis, Vice-Chairman Vincent M. O'Reilly, Treasurer Nina L. Doggett, Vice-Chairman Ray Stata, Vice-Chairman Harlan E. Anderson John F. Cogan, Jr. Edna S. -

Nietzsche, Debussy, and the Shadow of Wagner

NIETZSCHE, DEBUSSY, AND THE SHADOW OF WAGNER A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Tekla B. Babyak May 2014 ©2014 Tekla B. Babyak ii ABSTRACT NIETZSCHE, DEBUSSY, AND THE SHADOW OF WAGNER Tekla B. Babyak, Ph.D. Cornell University 2014 Debussy was an ardent nationalist who sought to purge all German (especially Wagnerian) stylistic features from his music. He claimed that he wanted his music to express his French identity. Much of his music, however, is saturated with markers of exoticism. My dissertation explores the relationship between his interest in musical exoticism and his anti-Wagnerian nationalism. I argue that he used exotic markers as a nationalistic reaction against Wagner. He perceived these markers as symbols of French identity. By the time that he started writing exotic music, in the 1890’s, exoticism was a deeply entrenched tradition in French musical culture. Many 19th-century French composers, including Felicien David, Bizet, Massenet, and Saint-Saëns, founded this tradition of musical exoticism and established a lexicon of exotic markers, such as modality, static harmonies, descending chromatic lines and pentatonicism. Through incorporating these markers into his musical style, Debussy gives his music a French nationalistic stamp. I argue that the German philosopher Nietzsche shaped Debussy’s nationalistic attitude toward musical exoticism. In 1888, Nietzsche asserted that Bizet’s musical exoticism was an effective antidote to Wagner. Nietzsche wrote that music should be “Mediterranized,” a dictum that became extremely famous in fin-de-siècle France. -

Northern Junket, Vol. 12, No. 8

* 'f^i^-^ ^v-;i=— ^W^ S!b X- Mr0 Jirf^ l.-f -<^v' jr. .'^'^r--. / I ,^-'.=i>. VOL 1/ MO b ima Article pagB Take It Or Leave It - - - 1 The Place Of Dancing In Sqtiare Dancing - 2 Where ? - - - - 6 They're All The Same - - - 9 The AiT3 Of Clare - - - 12 Dance Vorkahop, English Style - - 19 I Walk The Road Again - And Again - 23 Contra Danoe - Fisher's Hornpipe - - 29 Square Dance - Put Your Arms Around Me, Honey 30 Record Review - - - - 31 Adirondack Colonial Dancers - - 33 Book Review - - - - 38 It's Fan To Hunt - - - 40 What Tfcey Say In New England - - ^1,5 New England Folklore - - ' - 46 Wife Savers - - - - 48 Christmas isn't Just Foir Mdsl Give your friend a sub- scription to NORTHERN JUNKET i Only $4.53 for the next 10 issues. HERITAGE DANCES OF EAPJiY A^ffiRICA. My newest contra dan ce book. Send me your check of money order for $5.50 & I'll mail you an autographed copy by return mail. THE COUNTRY DANCE BOOK. The first dance book I wrote, now being re-issued. Send me yoxir check or money order for ^5 •SO and I'll send you an autographed copy by return mall. GR $10.00 for both to one address, Ralph Page, 117 Washington St, Keene, N.H, 03^31. TAKE IT OR LEAVE IT Two exciting things are becoming f^fff clear in this Bicentennial Year of sqtiare dancing. • at least in New England. •--X .- !• The great inter- est in the old Heritage lances of the yoTing college-aged dancers. -

2014-2015 Philharmonia No. 4

Lynn Philharmonia No. 4 2014-2015 Season Lynn Philharmonia Roster VIOLIN CELLO FRENCH HORN JunHeng Chen Patricia Cova Mileidy Gonzalez Erin David Akmal Irmatov Mateusz Jagiello Franz Felkl Trace Johnson Daniel Leon Wynton Grant Yuliya Kim Shaun Murray Herongia Han Elizabeth Lee Raul Rodriguez Xiaonan Huang Clarissa Vieira Clinton Soisson Julia Jakkel Hugo Valverde Villalobos Nora Lastre Shuyu Yao Jennifer Lee DOUBLE BASS Lilliana Marrero August Berger Cassidy Moore Evan Musgrave TRUMPET Yaroslava Poletaeva Jordan Nashman Zachary Brown Vijeta Sathyaraj Amy Nickler Ricardo Chinchilla Yalyen Savignon Isac Ryu Marianela Cordoba Kristen Seto Kevin Karabell Delcho Tenev FLUTE Mark Poljak Yordan Tenev Mark Huskey Natalie Smith Marija Trajkovska Jihee Kim Anna Tsukervanik Alla Sorokoletova TROMBONE Mozhu Yan Anastasia Tonina Mariana Cisneros Zongxi Li VIOLA OBOE Derek Mitchell Felicia Besan Paul Chinen Emily Nichols Brenton Caldwell Asako Furuoya Patricio Pinto Hao Chang Kelsey Maiorano Jordan Robison Josiah Coe Trevor Mansell Sean Colbert TUBA Zefang Fang CLARINET Joseph Guimaraes Roberto Henriquez Anna Brumbaugh Josue Jimenez Morales Miguel Fernandez Sonnak Jacqueline Gillette Nicole Kukieza Jesse Yukimura Amalia Wyrick-Flax Alberto Zilberstein PERCUSSION BASSOON Kirk Etheridge Hyunwook Bae Isaac Fernandez Hernandez Sebastian Castellanos Parker Lee Joshua Luty Jesse Monkman Ruth Santos 2 Lynn Philharmonia No. 4 Guillermo Figueroa, music director and conductor Saturday, February 7 – 7:30 p.m. Sunday, February 8 – 4 p.m. Keith C. and Elaine Johnson Wold Performing Arts Center Märchen von der schönen Melusine, Op. 32 Felix Mendelssohn (1809-1847) Concerto for Flute and Orchestra (2013) Behzad Ranjbaran (b. 1955) Jeffrey Khaner, flute INTERMISSION Harold en Italie, H 68 (1834) Hector Berlioz (1803-1869) Harold aux montagnes.