The Role of Social Identities in the Mental Health, Well-Being And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SPS 2012 Programme Final Draft RL

CONFERENCE PROGRAMME MONDAY 20 th AUGUST 2012 12:30 Postgraduate Workshop Lunch Atrium/Learning Cafe 13:30 MBS Seminar Room 1 Postgraduate Workshop “Research assessments, tuition fees, and funding cuts: A situated perspective on how to get a job in academia” Mario Weick, University of Kent 15:00 Refreshment Break Atrium/Learning Cafe 15:30 MBS Seminar Room 1 Postgraduate Workshop Sarah-Louise Quinnell TUESDAY 21 AUGUST 2012 08:00- Breakfast – for delegates staying on Monday 20 th 1 | P a g e BPS Social Psychology Section Annual Conference 2012, St Andrews University, 21-23 August 09:00 New Hall Dining Room Guided Walk around St Andrews 09:00 Conference Registration Opens Atrium/Learning Cafe 09:00- MBS Seminar Room 1 (50) 12:30 Postgraduate Workshop “New developments in academic writing” Jim Hartley, Keele University “Becoming an entrepreneur in Psychology” Jenna Condie, Salford University 10:00- MBS Meeting Room 3 (15) 12:00 BPS Social Psychology Section Committee Meeting (for committee members only) 11:00- Welcome Tea/Coffee and Exhibition 12:00 12:00 - Opening Buffet Lunch 13:00 13:00- Auditorium 14:00 Conference Opening Welcome: Evanthia Lyons (Queens University, Belfast, UK) Keynote Speaker: Associate Professor Isabel Menezes ( Universidade do Porto, Portugal) "Young Europeans: ‘Citizens in the making’ or political actors?" Chair: Stephen Gibson 2 | P a g e BPS Social Psychology Section Annual Conference 2012, St Andrews University, 21-23 August Parallel Session 1a Parallel Session 1b Parallel Session 1c Parallel Session 1d Parallel -

ABSTRACTS Scottish Undergraduate Conference

Title : The factors that influence memory strength: A study of episodic recollection and source precision Name and that of any co-author(s): Aamina Kauser Institution/organisation : University of Stirling Objectives/purpose The purpose of this experiment is to see if stimulus distinctiveness has a selective influence upon the precision of memory retrieval Design in this study we had used an independent measures design. The iv was whether the words were semantic or unrelated and the dv, whether the participant could remember the location of each word accurately. Background Harlow and Donaldson (2013) developed an objective continuous measure of successful episodic retrieval that does not rely on subjective reports such as confidence.the data shows recollection is a some or none process in which retrieval can fail but when successful can be more or less precise – i.e., recollection can be measured in terms of rate and precision. we know quite a lot about different factors that have an effect upon rate, but almost nothing is known about factors that influence retrieval precision. Methods 46 students participated through psych-web (24 for the 1st experiment, for semantic vs unrelated and 22 for experiment 2, semantic vs christian names).The experiment was designed and run using E-prime software. the data was then analysed through the e-prime software and excel. Results the results were analysed to find out the average shape, for both experiment 1 and 2. we analysed the results to find the lambda for both experiments. the lambda results show the rate, while the shape shows the precision. -

6 X 10.5 Long Title.P65

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-67115-6 - Coping with Minority Status: Responses to Exclusion and Inclusion Edited by Fabrizio Butera and John M. Levine Frontmatter More information Coping with Minority Status Responses to Exclusion and Inclusion Society consists of numerous interconnected, interacting, and interdependent groups, which differ in power and status. The consequences of belonging to a more powerful, higher status “majority” versus a less powerful, lower status “minority” can be profound, and the tensions that arise between these groups are the root of society’s most difficult problems. To understand the origins of these problems and develop solutions for them, it is necessary to understand the dynamics of majori- ty–minority relations. This volume brings together leading scholars in the fields of stigma, prejudice and discrimination, minority influence, and intergroup relations to provide diverse theoretical and methodological perspectives on what it means to be a minority. The volume, which focuses on the strategies that minorities use in coping with majorities, is organized into three parts: “Coping with exclusion: Being excluded for who you are”; “Coping with exclusion: Being excluded for what you think and do”; and “Coping with inclusion.” Fabrizio Butera is Professor of Social Psychology at the University of Lausanne, Switzerland, as well as director of the Social Psychology Laboratory. His research interests focus on social influence processes, conflict, and social comparison. He currently is a member of the Executive Committee of the European Association of Social Psychology and recently served as Associate Editor of the European Journal of Social Psychology. Professor Butera has published extensively in lead- ing journals in social psychology and has coedited several volumes, including Toward a Clarification of the Effects of Achievement Goals (with C. -

2006 Psychology Cat.Qxp

Psychology General Psychology 2 2006 Catalogue Developmental Psychology 5 Adolescent Development 10 Developmental Disorders 11 Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience 12 Teaching Psychology 12 NEW BOOKS Psychology of Education 13 KEY BACKLIST Psychology of Reading & Language 15 BESTSELLERS Psychology of Communication 17 KEY REFERENCE Research & Methodology 18 JOURNALS Personality & Intelligence 22 Social Psychology 23 Political Psychology 28 Psychology of Religion 28 History of Psychology 29 Biological & Comparative Psychology 30 Cognitive Psychology 32 Cognitive Neuroscience / Cognitive Science 34 How to use this interactive catalogue: Philosophy of the Mind 35 Industrial & Organizational Psychology 36 Clicking on the page numbers in the contents list will take you straight to that Clinical Psychology / Therapy & Psychoanalysis / Counselling 40 section. Health Psychology 41 Click on a book or journal title, cover Child & Adolescent Mental Health 42 image or URL to take you to the Family & Childhood Studies 42 corresponding page on the Blackwell Publishing website. Psychiatry 43 Intellectual Disability 44 Blackwell Publishing is not responsible for Forensic Psychology 45 the content of external websites. Index 46 GENERAL PSYCHOLOGY NEW EDITION A Companion to Psychological Younad og yhoclyPsychologyPs and You Amhon potrPgyochaslg,op tliani Anthropology An Informal Introduction Modernity and Psychocultural Change Third Edition B tRobre on,tCOdEgerN YR ELEditedCAYES, by CONERLY CASEY & ROBERT B. EDGERTON Both University of California, Los Angeles JULIA C. BERRYMAN, ELIZABETH M. OCKLEFORD, KEVIN HOWELLS, DAVID J. HARGREAVES & “Any publication which draws the attention of psychologists ZABNEITHLAUOKDEVNJHIRLAC IYEO MKVWFLR IGDW,R,DBEAU,INV ESRL DIANE J.WILDBUR University of Leicester; University of Leicester; University of South Australia; University of to the existence of other cultures is extremely welcome.. -

Children and the Capability Approach This Page Intentionally Left Blank Children and the Capability Approach

Children and the Capability Approach This page intentionally left blank Children and the Capability Approach Edited by Mario Biggeri University of Florence, Italy Jérôme Ballet Université de Versailles Saint-Quentin-en-Yvelines, France Flavio Comim St Edmund’s College, University of Cambridge, UK Selection and editorial matter © Mario Biggeri, Jérôme Ballet & Flavio Comim 2011 Individual chapters © their respective authors 2011 Prologue © Kaushik Basu 2011 Foreword © Mozaffar Qizilbash 2011 Softcover reprint of the hardcover 1st edition 2011 978-0-230-28481-4 All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without written permission. No portion of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted save with written permission or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, or under the terms of any licence permitting limited copying issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, Saffron House, 6-10 Kirby Street, London EC1N 8TS. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. The authors have asserted their rights to be identified as the authors of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. First published 2011 by PALGRAVE MACMILLAN Palgrave Macmillan in the UK is an imprint of Macmillan Publishers Limited, registered in England, company number 785998, of Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS. Palgrave Macmillan in the US is a division of St Martin’s Press LLC, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010. Palgrave Macmillan is the global academic imprint of the above companies and has companies and representatives throughout the world. -

2009 EBSP 21,2 (Pdf, 201

European Bulletin of Social Psychology EBSP, Volume 21, No. 2, December 2009 Editors: Xenia Chryssochoou & Sibylle Classen ISSN 1563-1001 1 Editorial 24 Reports of Previous Meetings Small Group Meeting on Cognitive Consistency as an Integrative 3 President’s Corner Concept in Social Cognition, June 11-15, 2009, Bronnbach, Germany 6 New Publications by Members Small Group Meeting on Self-Regulation Approaches to Group Processes, June 21-24, 2009, Hohenstein-Ödenwaldstetten, Germany Coping with Minority Status: Responses to Exclusion and Inclusion by F. Butera & J.M. Levine (eds.) Medium Size Meeting on Collective Action and Social Change: Towards Integration and Innovation, July 3-6, 2009, Appingedam, The Netherlands Psychological Perspectives on Ethical Behavior and Decision Making by D. DeCremer (ed.) Small Group Meeting on Resolving Societal Conflicts and Building Peace: Socio-Psychological Dynamics, September 7-10, 2009, Jerusalem, Israel Special Issue of Group Processes and Intergroup Relations, Guest editors: H. Giles, J.M. Hajda & D.L. Hamilton 44 Report from the Summer Institute in Social Psychology, Identities, Intergroup Relations and Acculturation. The Cornerstones of Intercultural Encounters by I. Jasinskaja-Lahti &. T.A. Mähönen (eds.) Evanston, Illinois, July 12-25, 2009 Arumentation and Education. Theoretical Foundations and Practices by 48 News about Members N. Muller Mirza & A.-N. Perret-Clermont (eds.) New Members of the Association Dominants et dominés: Les identités des collections et des agrégats (Dominants and subordinates: The social identities of collections and 51 Grants and Grant Reports aggregate) by F. Lorenzi-Cioldi Crossing the Divide: Intergroup Leadership in a World of Difference by T. Pittinsky (ed.) 76 News by Members Misogyny in Italian Media and Politics: The Voice of Social Psychology 19 Book Reviews The Psychology of Risk by G. -

The Development of National Identity in Childhood and Adolescence Martyn Barrett

The Development of National Identity in Childhood and Adolescence Martyn Barrett The Development of National Identity in Childhood and Adolescence Professor Martyn Barrett MA DPhil CPsychol FBPsS FRSA Professor of Psychology Department of Psychology School of Human Sciences University of Surrey Guildford Surrey GU2 7XH UK Inaugural lecture presented at the University of Surrey 22nd March, 2000 The Development of National Identity in Childhood and Adolescence Martyn Barrett The Development of National Identity in Childhood and Adolescence Inaugural lecture presented at the University of Surrey 22nd March, 2000 Professor Martyn Barrett MA DPhil CPsychol FBPsS FRSA In this lecture, I want to tell you about some of the research which I have been conducting in recent years. The focus of this research has been the psychology of national identity. In particu- lar, I have been investigating how people’s subjective sense of their own national identity develops during the course of their childhood and adolescence. People’s national identities are clearly an extremely potent force in the modern world. In the case of England, for example, the emotional response which sweeps across the nation whenever England plays Germany in a soccer match indicates the consid- erable importance which many English people attribute to their national identity. Such emotions are not unique to England. Similar emotions are tapped in many other countries as well on major sporting occasions. Witness the national pride which is aroused within a country when an athlete from that country wins a gold medal at the Olympic Games, or when the national soccer team wins the World Cup. -

University of Dundee DOCTOR of PHILOSOPHY the Role of Place In

University of Dundee DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY The role of place in perceived identity continuity Bowe, Mhairi Award date: 2012 Link to publication General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 26. Sep. 2021 DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY The Role of Place in Perceived Identity Continuity Mhairi Bowe 2012 University of Dundee Conditions for Use and Duplication Copyright of this work belongs to the author unless otherwise identified in the body of the thesis. It is permitted to use and duplicate this work only for personal and non-commercial research, study or criticism/review. You must obtain prior written consent from the author for any other use. Any quotation from this thesis must be acknowledged using the normal academic conventions. It is not permitted to supply the whole or part of this thesis to any other person or to post the same on any website or other online location without the prior written consent of the author. -

Catalogue 2007 Online Psychol

General Psychology 2 Developmental Psychology 4 Adolescent Development 11 Developmental Disorders 12 Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience 12 Psychology Psychology of Education 13 Teaching Psychology 14 200CATALOGUE7 Psychology of Reading & Language 15 Psychology of Communication 17 Research & Methodology 18 Personality & Intelligence 22 Social Psychology 22 Political Psychology 25 Psychology of Religion 25 History of Psychology 26 Biological & Comparative Psychology 26 Cognitive Psychology 28 new titles, key backlist, journals Cognitive Neuroscience / Cognitive Science 30 Philosophy of the Mind 31 Industrial & Organizational Psychology 32 Clinical Psychology 36 How to use this interactive catalogue: Therapy & Psychoanalysis 36 Clicking on the page numbers in the contents list Intellectual Disability 37 will take you straight to that section. Psychiatry 38 Click on a book or journal title, cover image or Child Psychiatry 40 URL to take you to the corresponding page on Family & Childhood Studies 40 the Blackwell Publishing website. Forensic Psychology 41 Blackwell Publishing is not responsible for the Index 42 content of external websites. GENERAL PSYCHOLOGY NEW KEY TEXTBOOK JOURNALS Psychological Science, Current Directions in Psychological Science, Psychological Science in the Public Interest and Perspectives in Psychological Science are all published Younad og yhoclyPsychologyPs and You on behalf of the Association for Psychological Science An Informal Introduction Current Directions in Third Edition encicS lacogihoclyPsn i onsitecrDi netrPsychologicalCur Science JULIA C. BERRYMAN, Edited by HARRY T. REIS ELIZABETH M. OCKLEFORD, www.blackwellpublishing.com/CDIR KEVIN HOWELLS, DAVID J. HARGREAVES & encicS lacogihoclyPsn i esvitpcesPerspectivesPre in Psychological Science .JAND EI WDL,BU.IR JDA NV IHKVEIA,RG RAMHEZV SEOBTH, I.WLE SL EOCOFKE,L.RDA UIJLDIANEBRE YM,AN J. -

The Experiment

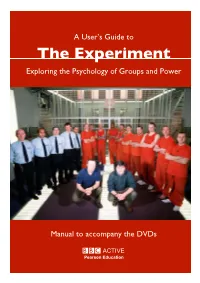

A User’s Guide to The Experiment Exploring the Psychology of Groups and Power Manual to accompany the DVDs B B C ACTIVE Pearson Education ii The Experiment Preamble Cover Photograph The participants (left to right) Guards: Brendan Grennan, Thufayel Ahmed, Tom McElroy, Tom Quarry, Frankie Caruana; Prisoners: Frank Clark, Derek McCabe, Paul Petken, John Edwards, Philip Bimpson, Ian Burnett, Dave Dawson, Kevin Murray, Neil Perry, Glen Payton The experimenters: Steve Reicher, Alex Haslam Second Edition ACTIVE Pearson Education ACTIVE © BBC Active, Pearson Education 2006 80 Strand London WC2R 0RL e-mail: [email protected] First edition published 2002 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, transmitted or utilised in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without permission in writing from the Publishers. British Library Cataloguing in Publication data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 0 563 54734 0 Library of Congress catalog card number record available The Experiment Contents iii About this Manual This manual provides material to accompany the BBC DVDs of the four episodes of The Experiment. It is intended to help students, teachers and practitioners reflect on the social and psychological issues that the programmes address and to help people get more out of their viewing experience — whether alone, in class, in a seminar, or in a workshop. On the one hand, the manual allows for a detailed understanding of what happened in The Experiment and of the lessons to be drawn from it.