Forum: W/G/S Studies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fugitive Life: Race, Gender, and the Rise of the Neoliberal-Carceral State

Fugitive Life: Race, Gender, and the Rise of the Neoliberal-Carceral State A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Stephen Dillon IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Regina Kunzel, Co-adviser Roderick Ferguson, Co-adviser May 2013 © Stephen Dillon, 2013 Acknowledgements Like so many of life’s joys, struggles, and accomplishments, this project would not have been possible without a vast community of friends, colleagues, mentors, and family. Before beginning the dissertation, I heard tales of its brutality, its crushing weight, and its endlessness. I heard stories of dropouts, madness, uncontrollable rage, and deep sadness. I heard rumors of people who lost time, love, and their curiosity. I was prepared to work 80 hours a week and to forget how to sleep. I was prepared to lose myself as so many said would happen. The support, love, and encouragement of those around me means I look back on writing this project with excitement, nostalgia, and appreciation. I am deeply humbled by the time, energy, and creativity that so many people loaned me. I hope one ounce of that collective passion shows on these pages. Without those listed here, and so many others, the stories I heard might have become more than gossip in the hallway or rumors over drinks. I will be forever indebted to Rod Ferguson’s simple yet life-altering advice: “write for one hour a day.” Adhering to this rule meant that writing became a part of me like never before. -

Bricolage Propriety: the Queer Practice of Black Uplift, 1890–1905

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 6-2017 Bricolage Propriety: The Queer Practice of Black Uplift, 1890–1905 Timothy M. Griffiths The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/2013 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] BRICOLAGE PROPRIETY: THE QUEER PRACTICE OF BLACK UPLIFT, 1890–1905 by TIMOTHY M. GRIFFITHS A Dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in English in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2017 Griffiths ii © 2017 TIMOTHY M. GRIFFITHS All Rights Reserved Griffiths iii Bricolage Propriety: The Queer Practice of Black Uplift, 1890–1905 by Timothy M. Griffiths This manuscript has been read and accepted by the Graduate Faculty in English in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ____________________ ______________________________________ Date Robert Reid-Pharr Chair of Examining Committee ____________________ ______________________________________ Date Mario DiGangi Executive Officer Supervisory Committee: Robert Reid-Pharr Eric Lott Duncan Faherty THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK Griffiths iv ABSTRACT Bricolage Propriety: The Queer Practice of Black Uplift, 1890–1905 by Timothy M. Griffiths Adviser: Robert Reid-Pharr Bricolage Propriety: The Queer Practice of Black Uplift, 1890-1905 situates the queer-of-color cultural imaginary in a relatively small nodal point: the United States at the end of the nineteenth century. -

The Immigrant and Asian American Politics of Visibility

ANXIETIES OF THE FICTIVE: THE IMMIGRANT AND ASIAN AMERICAN POLITICS OF VISIBILITY A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY SOYOUNG SONJIA HYON IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY RODERICK A. FERGUSON JOSEPHINE D. LEE ADVISERS JUNE 2011 © Soyoung Sonjia Hyon 2011 All Rights Reserved i Acknowledgements There are many collaborators to this dissertation. These are only some of them. My co-advisers Roderick Ferguson and Josephine Lee mentored me into intellectual maturity. Rod provided the narrative arc that structures this dissertation a long time ago and alleviated my anxieties of disciplinarity. He encouraged me to think of scholarship as an enjoyable practice and livelihood. Jo nudged me to focus on the things that made me curious and were fun. Her unflappable spirit was nourishing and provided a path to the finishing line. Karen Ho’s graduate seminar taught me a new language and framework to think through discourses of power that was foundational to my project. Her incisive insights always push my thinking to new grounds. The legends around Jigna Desai’s generosity and productive feedback proved true, and I am lucky to have her on my committee. The administrative staff and faculty in American Studies and Asian American Studies at the University of Minnesota have always been very patient and good to me. I recognize their efforts to tame unruly and manic graduate students like myself. I especially thank Melanie Steinman for her administrative prowess and generous spirit. Funding from the American Studies Department and the Leonard Memorial Film Fellowship supported this dissertation. -

Or Toward a Black Femme-Inist Criticism

Trans-Scripts 2 (2012) “Everything I know about being femme I learned from Sula” or Toward a Black Femme-inist Criticism Sydney Fonteyn Lewis* I came to Femme as defiance through a big booty that declined to be tucked under, bountiful breasts that refused to hide, insolent hair that can kink, and curl, and bead up, and lay straight all in one day, through my golden skin, against her caramel skin, against her chocolate skin, against her creamy skin. Through rainbows of sweaters, dresses, and shoes. Through my insubordinate body, defying subordination, incapable of assimilation, and tired, so tired of degradation. Through flesh and curves, and chafed thighs which learned from my grandma how Johnson’s Baby Powder can cure the chub rub. Through Toni Morrison, and Nella Larsen, and Audre Lorde, and Jewelle Gomez who, perhaps unwittingly, captured volumes of black femme lessons in their words. Through Billie Holiday who wore white gardenias while battling her inner darkness. Through my gay boyfriend who hummed show tunes and knew all the lyrics to “Baby Got Back,” which he sang to me with genuine admiration. Through shedding shame instead of shedding pounds, and learning that growing comfortable in my skin means finding comfort in her brownness. -Sydney Lewis, “I came to Femme through Fat and Black” My paper opens with an excerpt of a piece that I submitted to a fat positive anthology. In my piece, I articulate the genesis of my queer black femme- ininity through my identities as a black and fat body. My femme development is shaped by the intersections of those identities as much as those identities shape my expression of femme. -

Activism in Unsympathetic Environments: Queer Black Authors' Responses to Local Histories of Oppression

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 5-2019 Activism in Unsympathetic Environments: Queer Black Authors’ Responses to Local Histories of Oppression Jewel Lashelle Williams University of Tennessee, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Recommended Citation Williams, Jewel Lashelle, "Activism in Unsympathetic Environments: Queer Black Authors’ Responses to Local Histories of Oppression. " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2019. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/5455 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Jewel Lashelle Williams entitled "Activism in Unsympathetic Environments: Queer Black Authors’ Responses to Local Histories of Oppression." I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in English. Gerard Cohen-Vrignaud, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: Michelle Commander, Gichingiri Ndigirigi, Patrick Grzanka Accepted for the Council: Dixie L. Thompson Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) Activism in Unsympathetic Environments: Queer Black Authors’ Responses to Local Histories of Oppression A Dissertation Presented for the Doctor of Philosophy Degree The University of Tennessee, Knoxville Jewel Lashelle Williams May 2019 Copyright © 2018 by Jewel L. -

The Poetics and Pedagogy of Toni Cade Bambara, June Jordan, Audre Lorde, and Adrienne Rich in the Era of Open Admissions

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 5-2018 Insurgent Knowledge: The Poetics and Pedagogy of Toni Cade Bambara, June Jordan, Audre Lorde, and Adrienne Rich in the Era of Open Admissions Danica B. Savonick The Graduate Center, CUNY How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/2604 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] INSURGENT KNOWLEDGE: THE POETICS AND PEDAGOGY OF TONI CADE BAMBARA, JUNE JORDAN, AUDRE LORDE, AND ADRIENNE RICH IN THE ERA OF OPEN ADMISSIONS by DANICA SAVONICK A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in English in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2018 © 2018 DANICA SAVONICK All Rights Reserved ii Insurgent Knowledge: The Poetics and Pedagogy of Toni Cade Bambara, Audre Lorde, June Jordan, and Adrienne Rich in the Era of Open Admissions by Danica Savonick This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in English in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. _______________________ ___________________________________ Date Kandice Chuh Chair of Examining Committee _______________________ ___________________________________ Date Eric Lott Executive Officer Supervisory Committee: Cathy N. Davidson Michelle Fine Eric Lott Robert Reid-Pharr THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT Insurgent Knowledge: The Poetics and Pedagogy of Toni Cade Bambara, Audre Lorde, June Jordan, and Adrienne Rich in the Era of Open Admissions by Danica Savonick Advisor: Dr. -

The Invisible (And Hypervisible) Lesbian of Color in Theory, Publishing, and Media

Missing Bridges: The Invisible (and Hypervisible) Lesbian of Color in Theory, Publishing, and Media A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Renee Ann DeLong IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Maria Damon May 2013 Renee Ann DeLong copyright 2013 i I am indebted to the professors on my committee who helped guide me to the end of this journey: Dr. Omise'eke Tinsley, Dr. Patrick Bruch, Dr. Josephine Lee, and Dr. Roderick Ferguson. Rod read drafts generously, gave benedictions freely, and created the space for me to work within queer of color studies. He always reminded me that I was asking the right questions and welcomed me as a colleague. My adviser Dr. Maria Damon reserved many Friday mornings to talk me through the next steps of this project over double espressos. Her honesty helped me rethink my role as a scholar and educator as I began to plan the next phase of my career. Julie Enzer published a section of chapter two in Sinister Wisdom volume 82 as the article "Piecing Together Azalea: A Magazine for Third-World Lesbians 1977-1983." I am grateful for her early feedback and the permission to reprint the article within this dissertation. Taiyon Coleman was my sister in the struggle. Laura Bachinski kept me loved, grounded, humble, and laughing throughout the whole process. Thank you all. ii To Laura--my whole world. iii Abstract “Missing Bridges: The Invisible (and Hypervisible) Lesbian of Color in Theory, Publishing, and Media” While moving from theory, through the Women in Print Movement, and up to the current images of lesbians this dissertation considers how the figure of the lesbian of color has been erased and highlighted at different times and in different spaces. -

Valerie Lee and E. Patrick Johnson, Series Editors

BLACK PERFORMANCE AND CULTURAL CRITICISM Valerie Lee and E. Patrick Johnson, Series Editors The Queer Limit of Black Memory Black Lesbian Literature and Irresolution MATT RICHARDSON THE OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY PRESS COLUMBUS Copyright © 2013 by The Ohio State University. All rights reserved. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Richardson, Matt, 1969– The queer limit of Black memory : Black lesbian literature and irresolution / Matt Richard- son. p. cm.—(Black performance and cultural criticism) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-8142-1222-6 (cloth : alk. paper)—ISBN 978-0-8142-9323-2 (cd) 1. Lesbians in literature. 2. Lesbianism in literature. 3. Blacks in literature. 4. Gomez, Jew- elle, 1948—Criticism and interpretation. 5. Barnett, LaShonda K., 1975—Criticism and interpretation. 6. Adamz-Bogus, SDiane, 1946—Criticism and interpretation. 7. Brown, Laurinda D.—Criticism and interpretation. 8. Muhanji, Cherry—Criticism and interpre- tation. 9. Bridgforth, Sharon—Criticism and interpretation. 10. Kay, Jackie, 1961—Criti- cism and interpretation. 11. Brand, Dionne, 1953—Criticism and interpretation. I. Title. II. Series: Black performance and cultural criticism. PN56.L45R53 2013 809'.933526643—dc23 2012050159 Cover design by Thao Thai Text design by Juliet Williams Type set in Adobe Garamond Pro and Formata Printed by Thomson-Shore, Inc. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials. -

Resistance in and of the University: Neoliberalism, Empire, and Student Activist Movements

RESISTANCE IN AND OF THE UNIVERSITY: NEOLIBERALISM, EMPIRE, AND STUDENT ACTIVIST MOVEMENTS by Kristin Carey B.A., Colgate University, 2015 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE AND POSTDOCTORAL STUDIES (Gender, Race, Sexuality & Social Justice) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) April 2017 © Kristin Carey, 2017 Abstract In a time of global neoliberal precarity that follows from perpetual war, uncontracted and heightened forced global migration to name a few contemporary violences, there has been a noticeable rise of protest both nationally and also localized to university campuses in the United States. Experiencing the historical weight of racism, classism, sexism, ableism, and nationalism on college campuses, students are claiming public and digital spaces as sites of resistance. These movements trace connections to the accomplishments of the civil and academic rights movements of the 1960s, by again and still asking for institutional responses to white supremacy and systems of oppression (Ferguson, 2012) while realizing they take different shapes due to the international, national, and local forces that call them into being. This paper provides some preliminary mapping of the student activist and institutional responses to student movements. Necessarily, my work also historicizes the how the university is shaped by national and global political and economic violence and structures—namely, neoliberalism and empire. Using feminist, queer, and critical race theory as my theoretical and methodological frameworks, I examine two case studies of student protest: The University of California, San Diego of 2009 and the University of Missouri in 2015. -

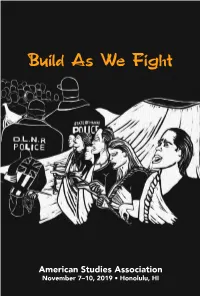

Build As We Fight

Build As We Fight American Studies Association November 7–10, 2019 • Honolulu, HI AMERICAN STUDIES ASSOCIATION PRESIDENTS, 1951 TO PRESENT Carl Bode, 1951–1952 Paul Lauter, 1994–1995 Charles Barker, 1953 Elaine Tyler May, 1995–1996 Robert E. Spiller, 1954–1955 Patricia Nelson Limerick, 1996–1997 George Rogers Taylor, 1956–1957 Mary Helen Washington, 1997–1998 Willard Thorp, 1958–1959 Janice Radway, 1998–1999 Ray Allen Billington, 1960–1961 Mary C. Kelley, 1999–2000 William Charvat, 1962 Michael Frisch, 2000–2001 Ralph Henry Gabriel, 1963–1964 George Sánchez, 2001–2002 Russel Blaine Nye, 1965–1966 Stephen H. Sumida, 2002–2003 John Hope Franklin, 1967 Amy Kaplan, 2003–2004 Norman Holmes Pearson, 1968 Shelley Fisher Fishkin, 2004–2005 Daniel J. Boorstin, 1969 Karen Halttunen, 2005–2006 Robert H. Walker, 1970–1971 Emory Elliott, 2006–2007 Daniel Aaron, 1972–1973 Vicki L. Ruiz, 2007–2008 William H. Goetzmann, 1974–1975 Philip J. Deloria, 2008–2009 Leo Marx, 1976–1977 Kevin K. Gaines, 2009–2010 Wilcomb E. Washburn, 1978–1979 Ruth Wilson Gilmore, 2010–2011 Robert F. Berkhofer Jr., 1980–1981 Priscilla Wald, 2011–2012 Sacvan Bercovitch, 1982–1983 Matthew Frye Jacobson, 2012–2013 Michael Cowan, 1984–1985 Curtis Marez, 2013–2014 Lois W. Banner, 1986–1987 Lisa Duggan, 2014–2015 Linda K. Kerber, 1988–1989 David Roediger, 2015–2016 Allen F. Davis, 1989–1990 Robert Warrior, 2016–2017 Martha Banta, 1990–1991 Kandice Chuh, 2017–2018 Alice Kessler-Harris, 1991–1992 Roderick Ferguson, 2018–2019 Cecelia Tichi, 1992–1993 Scott Kurashige, 2019–2020 Cathy N. Davidson, 1993–1994 Dylan Rodriguez, 2020–2021 COVER Our cover was designed bu Joy Lehuanani Enomoto, a mixed media visual artist and social justice activist. -

Girlhood Love and Queer Sorrow in Toni Morrison's

GIRLHOOD LOVE AND QUEER SORROW IN TONI MORRISON’S SULA Thesis submitted to the Department of English, Haverford College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts Madeleine Durante Haverford College Advisor: Professor Asali Solomon April 7, 2016 Durante 1 Toni Morrison’s 1973 novel, Sula, focuses above all else on an intense relationship between two women. In a conversation with Claudia Tate, Morrison argued, “Friendship between women is special, different, and has never been depicted as the major focus of a novel before Sula. Nobody ever talked about friendship between women” (157). Yet when critics engage Sula (frequently overshadowed by the works that preceded and followed it—1970’s The Bluest Eye and 1977’s Song of Solomon), they often take up the way it explodes the possibilities of storytelling. Sula breaks down simple binaries, and in doing so, offers an alternate conception of morality. It bends the limits of language through its integration of folk language and culture. It tells a story of a Black community largely without catering to the white gaze. The novel enacts these serious literary projects, yet it is ultimately concerned with the relationship between two girls who become women, Sula and Nel. The two girls meet in childhood dreams and find both love and a sense of self in the other. Their relationship produces pleasure, pain, guilt, and ultimately holds the two in thrall even after death, a literally haunting love and communion. Morrison published Sula in the moment of the Black Arts Movement, where Black writers spun urgent and political conversations over what constituted the Black Aesthetic.1 Sula creates its own formative aesthetic set while centralizing the relationship between two women, pushing boundaries of sexual freedom, relationality, and language. -

Queer of Color Theory Draft Syllabus Title: Queer of Color Theorizing And

Queer of Color Theory Draft Syllabus Title: Queer of Color Theorizing and Perspectives Short Title for Banner: Queer of Color Theorizing Course Prefix and Number: WS 381 Prerequisites and Co-Requisites: Pre-req WS 360U Intro to Queer Studies Course Description Queer of color critique, along with trans of color and queer indigenous/Two-Spirit approaches, are modes of queer theory that have emerged primarily from scholars in the United States working at the critical intersections of queer studies, women of color feminisms, immigration and diaspora scholarship, and ethnic studies. Queer of color critique, a term often credited to Rod Ferguson, centers the intellectual traditions of queer thinkers of color such as James Baldwin and (often queer) women of color feminists such as Audre Lorde, Gloria Anzaldua, and Cherrie Moraga. A central goal of this course will be to understand how the categories of race, ethnicity, gender, sexuality, and nation are mutually constitutive through critical race, feminist, queer, decolonial, and materialist analyses and epistemologies that have been deployed by queer of color theorists. This course will provide an overview of the development and foundational approaches to queer of color theorizing as well as an opportunity to apply these theories to contemporary issues and experiences. Catalog Course description (50 words max) Utilizing critical race, feminist, queer, decolonial, and materialist analyses, queer of color theories highlight the intersections of race, sexuality, and nations. This course provides an overview of the development and foundational approaches to queer of color critiques, as well as an opportunity to apply these theories to contemporary issues. Course Objectives ● Provide an overview of the genealogies and foundational texts of queer of color critique and theories, including queer indigenous/Two-Spirit and transgender approaches.