John Dalton's Atomic Theory: Using the History and Nature of Science to Teach Particle Concepts?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Practice of Chemistry Education (Paper)

CHEMISTRY EDUCATION: THE PRACTICE OF CHEMISTRY EDUCATION RESEARCH AND PRACTICE (PAPER) 2004, Vol. 5, No. 1, pp. 69-87 Concept teaching and learning/ History and philosophy of science (HPS) Juan QUÍLEZ IES José Ballester, Departamento de Física y Química, Valencia (Spain) A HISTORICAL APPROACH TO THE DEVELOPMENT OF CHEMICAL EQUILIBRIUM THROUGH THE EVOLUTION OF THE AFFINITY CONCEPT: SOME EDUCATIONAL SUGGESTIONS Received 20 September 2003; revised 11 February 2004; in final form/accepted 20 February 2004 ABSTRACT: Three basic ideas should be considered when teaching and learning chemical equilibrium: incomplete reaction, reversibility and dynamics. In this study, we concentrate on how these three ideas have eventually defined the chemical equilibrium concept. To this end, we analyse the contexts of scientific inquiry that have allowed the growth of chemical equilibrium from the first ideas of chemical affinity. At the beginning of the 18th century, chemists began the construction of different affinity tables, based on the concept of elective affinities. Berthollet reworked this idea, considering that the amount of the substances involved in a reaction was a key factor accounting for the chemical forces. Guldberg and Waage attempted to measure those forces, formulating the first affinity mathematical equations. Finally, the first ideas providing a molecular interpretation of the macroscopic properties of equilibrium reactions were presented. The historical approach of the first key ideas may serve as a basis for an appropriate sequencing of -

The History of the Concept of Element, with Particular Reference to Humphry Davy

The Physical Sciences Initiative The history of the concept of element, with particular reference to Humphry Davy One of the problems highlighted when the recently implemented chemistry syllabus was being developed was the difficulty caused by starting the teaching of the course with atoms. The new syllabus offers a possible alternative teaching order that starts at the macroscopic level, and deals with elements. If this is done, the history of the idea of elements is dealt with at a very early stage. The concept of element originated with the ancient Greeks, notably Empedocles, who around 450 BC defined elements as the basic building blocks from which all other materials are made. He stated that there were four elements: earth, air, fire and water. Substances were said to change when elements break apart and recombine under the action of the forces of strife and love. Little progress was made in this area until the seventeenth century AD. The fruitless attempts of the alchemists to change base metals such as lead into gold and to find the “elixir of life” held back progress, although much chemical knowledge and expertise was gained. In 1661, 1 The Physical Sciences Initiative The Physical Sciences Initiative Robert Boyle defined an element as a substance that cannot be broken down into simpler materials. He cast doubt on the Greek elements, and provided a criterion for showing that a material was not an element. Robert Boyle Many elements were discovered during the next 100 years, but progress was delayed by the phlogiston hypothesis. According to this hypothesis, when a substance was burned it lost a substance called phlogiston to the air. -

Historical Development of the Periodic Classification of the Chemical Elements

THE HISTORICAL DEVELOPMENT OF THE PERIODIC CLASSIFICATION OF THE CHEMICAL ELEMENTS by RONALD LEE FFISTER B. S., Kansas State University, 1962 A MASTER'S REPORT submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree FASTER OF SCIENCE Department of Physical Science KANSAS STATE UNIVERSITY Manhattan, Kansas 196A Approved by: Major PrafeLoor ii |c/ TABLE OF CONTENTS t<y THE PROBLEM AND DEFINITION 0? TEH-IS USED 1 The Problem 1 Statement of the Problem 1 Importance of the Study 1 Definition of Terms Used 2 Atomic Number 2 Atomic Weight 2 Element 2 Periodic Classification 2 Periodic Lav • • 3 BRIEF RtiVJiM OF THE LITERATURE 3 Books .3 Other References. .A BACKGROUND HISTORY A Purpose A Early Attempts at Classification A Early "Elements" A Attempts by Aristotle 6 Other Attempts 7 DOBEREBIER'S TRIADS AND SUBSEQUENT INVESTIGATIONS. 8 The Triad Theory of Dobereiner 10 Investigations by Others. ... .10 Dumas 10 Pettehkofer 10 Odling 11 iii TEE TELLURIC EELIX OF DE CHANCOURTOIS H Development of the Telluric Helix 11 Acceptance of the Helix 12 NEWLANDS' LAW OF THE OCTAVES 12 Newlands' Chemical Background 12 The Law of the Octaves. .........' 13 Acceptance and Significance of Newlands' Work 15 THE CONTRIBUTIONS OF LOTHAR MEYER ' 16 Chemical Background of Meyer 16 Lothar Meyer's Arrangement of the Elements. 17 THE WORK OF MENDELEEV AND ITS CONSEQUENCES 19 Mendeleev's Scientific Background .19 Development of the Periodic Law . .19 Significance of Mendeleev's Table 21 Atomic Weight Corrections. 21 Prediction of Hew Elements . .22 Influence -

The Development of the Periodic Table and Its Consequences Citation: J

Firenze University Press www.fupress.com/substantia The Development of the Periodic Table and its Consequences Citation: J. Emsley (2019) The Devel- opment of the Periodic Table and its Consequences. Substantia 3(2) Suppl. 5: 15-27. doi: 10.13128/Substantia-297 John Emsley Copyright: © 2019 J. Emsley. This is Alameda Lodge, 23a Alameda Road, Ampthill, MK45 2LA, UK an open access, peer-reviewed article E-mail: [email protected] published by Firenze University Press (http://www.fupress.com/substantia) and distributed under the terms of the Abstract. Chemistry is fortunate among the sciences in having an icon that is instant- Creative Commons Attribution License, ly recognisable around the world: the periodic table. The United Nations has deemed which permits unrestricted use, distri- 2019 to be the International Year of the Periodic Table, in commemoration of the 150th bution, and reproduction in any medi- anniversary of the first paper in which it appeared. That had been written by a Russian um, provided the original author and chemist, Dmitri Mendeleev, and was published in May 1869. Since then, there have source are credited. been many versions of the table, but one format has come to be the most widely used Data Availability Statement: All rel- and is to be seen everywhere. The route to this preferred form of the table makes an evant data are within the paper and its interesting story. Supporting Information files. Keywords. Periodic table, Mendeleev, Newlands, Deming, Seaborg. Competing Interests: The Author(s) declare(s) no conflict of interest. INTRODUCTION There are hundreds of periodic tables but the one that is widely repro- duced has the approval of the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) and is shown in Fig.1. -

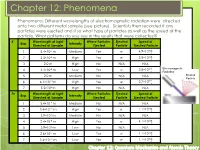

Chapter 12: Phenomena

Chapter 12: Phenomena Phenomena: Different wavelengths of electromagnetic radiation were directed onto two different metal sample (see picture). Scientists then recorded if any particles were ejected and if so what type of particles as well as the speed of the particle. What patterns do you see in the results that were collected? K Wavelength of Light Where Particles Ejected Speed of Exp. Intensity Directed at Sample Ejected Particle Ejected Particle -7 - 4 푚 1 5.4×10 m Medium Yes e 4.9×10 푠 -8 - 6 푚 2 3.3×10 m High Yes e 3.5×10 푠 3 2.0 m High No N/A N/A 4 3.3×10-8 m Low Yes e- 3.5×106 푚 Electromagnetic 푠 Radiation 5 2.0 m Medium No N/A N/A Ejected Particle -12 - 8 푚 6 6.1×10 m High Yes e 2.7×10 푠 7 5.5×104 m High No N/A N/A Fe Wavelength of Light Where Particles Ejected Speed of Exp. Intensity Directed at Sample Ejected Particle Ejected Particle 1 5.4×10-7 m Medium No N/A N/A -11 - 8 푚 2 3.4×10 m High Yes e 1.1×10 푠 3 3.9×103 m Medium No N/A N/A -8 - 6 푚 4 2.4×10 m High Yes e 4.1×10 푠 5 3.9×103 m Low No N/A N/A -7 - 5 푚 6 2.6×10 m Low Yes e 1.1×10 푠 -11 - 8 푚 7 3.4×10 m Low Yes e 1.1×10 푠 Chapter 12: Quantum Mechanics and Atomic Theory Chapter 12: Quantum Mechanics and Atomic Theory o Electromagnetic Radiation o Quantum Theory o Particle in a Box Big Idea: The structure of atoms o The Hydrogen Atom must be explained o Quantum Numbers using quantum o Orbitals mechanics, a theory in o Many-Electron Atoms which the properties of particles and waves o Periodic Trends merge together. -

Introduction to Chemistry

Introduction to Chemistry Author: Tracy Poulsen Digital Proofer Supported by CK-12 Foundation CK-12 Foundation is a non-profit organization with a mission to reduce the cost of textbook Introduction to Chem... materials for the K-12 market both in the U.S. and worldwide. Using an open-content, web-based Authored by Tracy Poulsen collaborative model termed the “FlexBook,” CK-12 intends to pioneer the generation and 8.5" x 11.0" (21.59 x 27.94 cm) distribution of high-quality educational content that will serve both as core text as well as provide Black & White on White paper an adaptive environment for learning. 250 pages ISBN-13: 9781478298601 Copyright © 2010, CK-12 Foundation, www.ck12.org ISBN-10: 147829860X Except as otherwise noted, all CK-12 Content (including CK-12 Curriculum Material) is made Please carefully review your Digital Proof download for formatting, available to Users in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution/Non-Commercial/Share grammar, and design issues that may need to be corrected. Alike 3.0 Unported (CC-by-NC-SA) License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc- sa/3.0/), as amended and updated by Creative Commons from time to time (the “CC License”), We recommend that you review your book three times, with each time focusing on a different aspect. which is incorporated herein by this reference. Specific details can be found at http://about.ck12.org/terms. Check the format, including headers, footers, page 1 numbers, spacing, table of contents, and index. 2 Review any images or graphics and captions if applicable. -

Atomic Physicsphysics AAA Powerpointpowerpointpowerpoint Presentationpresentationpresentation Bybyby Paulpaulpaul E.E.E

ChapterChapter 38C38C -- AtomicAtomic PhysicsPhysics AAA PowerPointPowerPointPowerPoint PresentationPresentationPresentation bybyby PaulPaulPaul E.E.E. Tippens,Tippens,Tippens, ProfessorProfessorProfessor ofofof PhysicsPhysicsPhysics SouthernSouthernSouthern PolytechnicPolytechnicPolytechnic StateStateState UniversityUniversityUniversity © 2007 Objectives:Objectives: AfterAfter completingcompleting thisthis module,module, youyou shouldshould bebe ableable to:to: •• DiscussDiscuss thethe earlyearly modelsmodels ofof thethe atomatom leadingleading toto thethe BohrBohr theorytheory ofof thethe atom.atom. •• DemonstrateDemonstrate youryour understandingunderstanding ofof emissionemission andand absorptionabsorption spectraspectra andand predictpredict thethe wavelengthswavelengths oror frequenciesfrequencies ofof thethe BalmerBalmer,, LymanLyman,, andand PashenPashen spectralspectral series.series. •• CalculateCalculate thethe energyenergy emittedemitted oror absorbedabsorbed byby thethe hydrogenhydrogen atomatom whenwhen thethe electronelectron movesmoves toto aa higherhigher oror lowerlower energyenergy level.level. PropertiesProperties ofof AtomsAtoms ••• AtomsAtomsAtoms areareare stablestablestable andandand electricallyelectricallyelectrically neutral.neutral.neutral. ••• AtomsAtomsAtoms havehavehave chemicalchemicalchemical propertiespropertiesproperties whichwhichwhich allowallowallow themthemthem tototo combinecombinecombine withwithwith otherotherother atoms.atoms.atoms. ••• AtomsAtomsAtoms emitemitemit andandand absorbabsorbabsorb -

22. Atomic Physics and Quantum Mechanics

22. Atomic Physics and Quantum Mechanics S. Teitel April 14, 2009 Most of what you have been learning this semester and last has been 19th century physics. Indeed, Maxwell's theory of electromagnetism, combined with Newton's laws of mechanics, seemed at that time to express virtually a complete \solution" to all known physical problems. However, already by the 1890's physicists were grappling with certain experimental observations that did not seem to fit these existing theories. To explain these puzzling phenomena, the early part of the 20th century witnessed revolutionary new ideas that changed forever our notions about the physical nature of matter and the theories needed to explain how matter behaves. In this lecture we hope to give the briefest introduction to some of these ideas. 1 Photons You have already heard in lecture 20 about the photoelectric effect, in which light shining on the surface of a metal results in the emission of electrons from that surface. To explain the observed energies of these emitted elec- trons, Einstein proposed in 1905 that the light (which Maxwell beautifully explained as an electromagnetic wave) should be viewed as made up of dis- crete particles. These particles were called photons. The energy of a photon corresponding to a light wave of frequency f is given by, E = hf ; where h = 6:626×10−34 J · s is a new fundamental constant of nature known as Planck's constant. The total energy of a light wave, consisting of some particular number n of photons, should therefore be quantized in integer multiples of the energy of the individual photon, Etotal = nhf. -

Atomic Theory - Review Sheet

Atomic Theory - Review Sheet You should understand the contribution of each scientist. I don't expect you to memorize dates, but I do want to know what each scientist contributed to the theory. Democretus - 400 B.C. - theory that matter is made of atoms Boyle 1622 -1691 - defined element Lavoisier 1743-1797 - pioneer of modern chemistry (careful and controlled experiments) - conservation of mass (understand his experiment and compare to the lab "Does mass change in a chemical reaction?") Proust 1799 - law of constant composition (or definite proportions) - understand this law and relate it to the Hydrogen and Oxygen generation lab Dalton 1808 - Understand the meaning of each part of Dalton's atomic theory. - You don't have to memorize the five parts, just understand what they mean. - You should know which parts we now know are not true (according to modern atomic theory). Black Box Model Crookes 1870 - Crookes tube - Know how this is constructed (Know how cathode rays are generated and what they are.) J.J. Thomsen - 1890 - How did he expand on Crookes' experiment? - discovered the electron - negative particles in all of matter (all atoms) - must also be positive parts Lord Kelvin - near Thomsen's time Plum Pudding Model - plum pudding model Henri Becquerel - 1896 - discovered radioactivity of uranium Marie Curie - 1905 - received Nobel prize (shared with her husband Pierre Curie and Henri Bequerel) for her work in studying radiation. - Name the three kinds of radiation and describe each type. Rutheford - 1910 - Understand the gold foil experiment - How was it set up? - What did it show? - Discovered the proton Hard Nucleus Model - new model of atom (positively charged, very dense nucleus) Niels Bohr - 1913 - Bohr model of the atom - electrons in specific orbits with specific energies James Chadwick - 1932 - discovered the electron Modern version of atom - 1950 Bohr Model - similar nucleus (protons + neutrons) - electrons in orbitals not orbits Bohr Model Understand isotopes, atomic mass, mass #, atomic #, ions (with neutrons) Nature of light - wavelength vs. -

Chapter 11: Modernatomictheory 105

CHAPTER 11 Modern Atomic Theory INTRODUCTION It is difficult to form a mental image of atoms because we can’t see them. Scientists have produced models that account for the behavior of atoms by making observations about the properties of atoms. So we know quite a bit about these tiny particles which make up matter even though we cannot see them. In this chapter you will learn how chemists believe atoms are structured. CHAPTER DISCUSSION This is yet another chapter in which models play a significant role. Recall that we like models to be simple, but we also need models to explain the questions we want to answer. For example, Dalton’s model of the atom has the advantage of being quite simple and is useful when considering molecular- level views of solids, liquids, and gases and in representing chemical equations. However, it cannot explain fundamental questions such as why atoms “stick” together to form molecules. Scientists such as Thomson and Rutherford expanded the model of the atom to include subatomic particles. The model is more complicated than Dalton’s, but it begins to explain chemical reactivity (electrons are involved) and formulas for ionic compounds. But questions still abound. For example, why are there similarities in reactivities of elements (periodic trends)? To begin our understanding of modern atomic theory, let’s first discuss some observations. For example, you have undoubtedly seen a fireworks display, either in person or on television. Where do the colors come from? How do we get so many different colors? It turns out that different salts, when heated, give off different colors. -

Electrochemistry a Chem1 Supplement Text Stephen K

Electrochemistry a Chem1 Supplement Text Stephen K. Lower Simon Fraser University Contents 1 Chemistry and electricity 2 Electroneutrality .............................. 3 Potential dierences at interfaces ..................... 4 2 Electrochemical cells 5 Transport of charge within the cell .................... 7 Cell description conventions ........................ 8 Electrodes and electrode reactions .................... 8 3 Standard half-cell potentials 10 Reference electrodes ............................ 12 Prediction of cell potentials ........................ 13 Cell potentials and the electromotive series ............... 14 Cell potentials and free energy ...................... 15 The fall of the electron ........................... 17 Latimer diagrams .............................. 20 4 The Nernst equation 21 Concentration cells ............................. 23 Analytical applications of the Nernst equation .............. 23 Determination of solubility products ................ 23 Potentiometric titrations ....................... 24 Measurement of pH .......................... 24 Membrane potentials ............................ 26 5 Batteries and fuel cells 29 The fuel cell ................................. 29 1 CHEMISTRY AND ELECTRICITY 2 6 Electrochemical Corrosion 31 Control of corrosion ............................ 34 7 Electrolytic cells 34 Electrolysis involving water ........................ 35 Faraday’s laws of electrolysis ....................... 36 Industrial electrolytic processes ...................... 37 The chloralkali -

A Short History of Chemistry J.R.Partington January 22-29, 2017

A Short History of Chemistry J.R.Partington January 22-29, 2017 What are the major discoveries in Chemistry, who are the mayor players? When it comes to (classical) music, ten composers cover most of it that deserves to be part of the indispensable culture, when it comes to painting let us say a hundred might be necessary, and as to literature, maybe a thousand. What about mathematics, physics and chemistry? Here the situation may be thought of as more complicated as many minor workers, if not individually at least collectively, have contributed significantly to the discipline, and this might be particularly the case with chemistry, which more than mathematics and physics depends on tedious work carried out by armies of anonymous toilers in laboratories. But Chemistry is not just routine work but as any science depends on daring hypotheses and flights of fancy to be confronted with an unforgiving empirical reality. Who are the Gausses and Eulers of Chemistry, to say nothing of a Newton. Is there in analogy with Bell’s ’Men of Mathematics’ a corresponding compilation of chemical heroes? In one sense there is, names such as Scheele, Priestley. Pasteure, may be more well-known to the general public than Gauss, Euler or Lagrange. On the other hand a mathematician taking part of the cavalcade is invariably a bit disappointed, none of the names mentioned and lauded, seem to have the same luster as the kings of mathematics, instead diligence and conscientious steadfast work seems to carry the day. In one way it is unfair, in spite of mathematics supposedly being the least accessible of all the sciences, literally it is the opposite, being entirely cerebral.