Constitution and Model: Bohr's Quantum Theory and Imagining The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

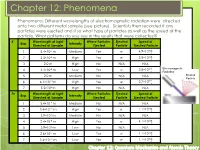

Chapter 12: Phenomena

Chapter 12: Phenomena Phenomena: Different wavelengths of electromagnetic radiation were directed onto two different metal sample (see picture). Scientists then recorded if any particles were ejected and if so what type of particles as well as the speed of the particle. What patterns do you see in the results that were collected? K Wavelength of Light Where Particles Ejected Speed of Exp. Intensity Directed at Sample Ejected Particle Ejected Particle -7 - 4 푚 1 5.4×10 m Medium Yes e 4.9×10 푠 -8 - 6 푚 2 3.3×10 m High Yes e 3.5×10 푠 3 2.0 m High No N/A N/A 4 3.3×10-8 m Low Yes e- 3.5×106 푚 Electromagnetic 푠 Radiation 5 2.0 m Medium No N/A N/A Ejected Particle -12 - 8 푚 6 6.1×10 m High Yes e 2.7×10 푠 7 5.5×104 m High No N/A N/A Fe Wavelength of Light Where Particles Ejected Speed of Exp. Intensity Directed at Sample Ejected Particle Ejected Particle 1 5.4×10-7 m Medium No N/A N/A -11 - 8 푚 2 3.4×10 m High Yes e 1.1×10 푠 3 3.9×103 m Medium No N/A N/A -8 - 6 푚 4 2.4×10 m High Yes e 4.1×10 푠 5 3.9×103 m Low No N/A N/A -7 - 5 푚 6 2.6×10 m Low Yes e 1.1×10 푠 -11 - 8 푚 7 3.4×10 m Low Yes e 1.1×10 푠 Chapter 12: Quantum Mechanics and Atomic Theory Chapter 12: Quantum Mechanics and Atomic Theory o Electromagnetic Radiation o Quantum Theory o Particle in a Box Big Idea: The structure of atoms o The Hydrogen Atom must be explained o Quantum Numbers using quantum o Orbitals mechanics, a theory in o Many-Electron Atoms which the properties of particles and waves o Periodic Trends merge together. -

Introduction to Chemistry

Introduction to Chemistry Author: Tracy Poulsen Digital Proofer Supported by CK-12 Foundation CK-12 Foundation is a non-profit organization with a mission to reduce the cost of textbook Introduction to Chem... materials for the K-12 market both in the U.S. and worldwide. Using an open-content, web-based Authored by Tracy Poulsen collaborative model termed the “FlexBook,” CK-12 intends to pioneer the generation and 8.5" x 11.0" (21.59 x 27.94 cm) distribution of high-quality educational content that will serve both as core text as well as provide Black & White on White paper an adaptive environment for learning. 250 pages ISBN-13: 9781478298601 Copyright © 2010, CK-12 Foundation, www.ck12.org ISBN-10: 147829860X Except as otherwise noted, all CK-12 Content (including CK-12 Curriculum Material) is made Please carefully review your Digital Proof download for formatting, available to Users in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution/Non-Commercial/Share grammar, and design issues that may need to be corrected. Alike 3.0 Unported (CC-by-NC-SA) License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc- sa/3.0/), as amended and updated by Creative Commons from time to time (the “CC License”), We recommend that you review your book three times, with each time focusing on a different aspect. which is incorporated herein by this reference. Specific details can be found at http://about.ck12.org/terms. Check the format, including headers, footers, page 1 numbers, spacing, table of contents, and index. 2 Review any images or graphics and captions if applicable. -

Atomic Physicsphysics AAA Powerpointpowerpointpowerpoint Presentationpresentationpresentation Bybyby Paulpaulpaul E.E.E

ChapterChapter 38C38C -- AtomicAtomic PhysicsPhysics AAA PowerPointPowerPointPowerPoint PresentationPresentationPresentation bybyby PaulPaulPaul E.E.E. Tippens,Tippens,Tippens, ProfessorProfessorProfessor ofofof PhysicsPhysicsPhysics SouthernSouthernSouthern PolytechnicPolytechnicPolytechnic StateStateState UniversityUniversityUniversity © 2007 Objectives:Objectives: AfterAfter completingcompleting thisthis module,module, youyou shouldshould bebe ableable to:to: •• DiscussDiscuss thethe earlyearly modelsmodels ofof thethe atomatom leadingleading toto thethe BohrBohr theorytheory ofof thethe atom.atom. •• DemonstrateDemonstrate youryour understandingunderstanding ofof emissionemission andand absorptionabsorption spectraspectra andand predictpredict thethe wavelengthswavelengths oror frequenciesfrequencies ofof thethe BalmerBalmer,, LymanLyman,, andand PashenPashen spectralspectral series.series. •• CalculateCalculate thethe energyenergy emittedemitted oror absorbedabsorbed byby thethe hydrogenhydrogen atomatom whenwhen thethe electronelectron movesmoves toto aa higherhigher oror lowerlower energyenergy level.level. PropertiesProperties ofof AtomsAtoms ••• AtomsAtomsAtoms areareare stablestablestable andandand electricallyelectricallyelectrically neutral.neutral.neutral. ••• AtomsAtomsAtoms havehavehave chemicalchemicalchemical propertiespropertiesproperties whichwhichwhich allowallowallow themthemthem tototo combinecombinecombine withwithwith otherotherother atoms.atoms.atoms. ••• AtomsAtomsAtoms emitemitemit andandand absorbabsorbabsorb -

22. Atomic Physics and Quantum Mechanics

22. Atomic Physics and Quantum Mechanics S. Teitel April 14, 2009 Most of what you have been learning this semester and last has been 19th century physics. Indeed, Maxwell's theory of electromagnetism, combined with Newton's laws of mechanics, seemed at that time to express virtually a complete \solution" to all known physical problems. However, already by the 1890's physicists were grappling with certain experimental observations that did not seem to fit these existing theories. To explain these puzzling phenomena, the early part of the 20th century witnessed revolutionary new ideas that changed forever our notions about the physical nature of matter and the theories needed to explain how matter behaves. In this lecture we hope to give the briefest introduction to some of these ideas. 1 Photons You have already heard in lecture 20 about the photoelectric effect, in which light shining on the surface of a metal results in the emission of electrons from that surface. To explain the observed energies of these emitted elec- trons, Einstein proposed in 1905 that the light (which Maxwell beautifully explained as an electromagnetic wave) should be viewed as made up of dis- crete particles. These particles were called photons. The energy of a photon corresponding to a light wave of frequency f is given by, E = hf ; where h = 6:626×10−34 J · s is a new fundamental constant of nature known as Planck's constant. The total energy of a light wave, consisting of some particular number n of photons, should therefore be quantized in integer multiples of the energy of the individual photon, Etotal = nhf. -

Atomic Theory - Review Sheet

Atomic Theory - Review Sheet You should understand the contribution of each scientist. I don't expect you to memorize dates, but I do want to know what each scientist contributed to the theory. Democretus - 400 B.C. - theory that matter is made of atoms Boyle 1622 -1691 - defined element Lavoisier 1743-1797 - pioneer of modern chemistry (careful and controlled experiments) - conservation of mass (understand his experiment and compare to the lab "Does mass change in a chemical reaction?") Proust 1799 - law of constant composition (or definite proportions) - understand this law and relate it to the Hydrogen and Oxygen generation lab Dalton 1808 - Understand the meaning of each part of Dalton's atomic theory. - You don't have to memorize the five parts, just understand what they mean. - You should know which parts we now know are not true (according to modern atomic theory). Black Box Model Crookes 1870 - Crookes tube - Know how this is constructed (Know how cathode rays are generated and what they are.) J.J. Thomsen - 1890 - How did he expand on Crookes' experiment? - discovered the electron - negative particles in all of matter (all atoms) - must also be positive parts Lord Kelvin - near Thomsen's time Plum Pudding Model - plum pudding model Henri Becquerel - 1896 - discovered radioactivity of uranium Marie Curie - 1905 - received Nobel prize (shared with her husband Pierre Curie and Henri Bequerel) for her work in studying radiation. - Name the three kinds of radiation and describe each type. Rutheford - 1910 - Understand the gold foil experiment - How was it set up? - What did it show? - Discovered the proton Hard Nucleus Model - new model of atom (positively charged, very dense nucleus) Niels Bohr - 1913 - Bohr model of the atom - electrons in specific orbits with specific energies James Chadwick - 1932 - discovered the electron Modern version of atom - 1950 Bohr Model - similar nucleus (protons + neutrons) - electrons in orbitals not orbits Bohr Model Understand isotopes, atomic mass, mass #, atomic #, ions (with neutrons) Nature of light - wavelength vs. -

Chapter 11: Modernatomictheory 105

CHAPTER 11 Modern Atomic Theory INTRODUCTION It is difficult to form a mental image of atoms because we can’t see them. Scientists have produced models that account for the behavior of atoms by making observations about the properties of atoms. So we know quite a bit about these tiny particles which make up matter even though we cannot see them. In this chapter you will learn how chemists believe atoms are structured. CHAPTER DISCUSSION This is yet another chapter in which models play a significant role. Recall that we like models to be simple, but we also need models to explain the questions we want to answer. For example, Dalton’s model of the atom has the advantage of being quite simple and is useful when considering molecular- level views of solids, liquids, and gases and in representing chemical equations. However, it cannot explain fundamental questions such as why atoms “stick” together to form molecules. Scientists such as Thomson and Rutherford expanded the model of the atom to include subatomic particles. The model is more complicated than Dalton’s, but it begins to explain chemical reactivity (electrons are involved) and formulas for ionic compounds. But questions still abound. For example, why are there similarities in reactivities of elements (periodic trends)? To begin our understanding of modern atomic theory, let’s first discuss some observations. For example, you have undoubtedly seen a fireworks display, either in person or on television. Where do the colors come from? How do we get so many different colors? It turns out that different salts, when heated, give off different colors. -

S 1-5 1. Define Each of the Following: A. Atom B. Electron C. Nucleus D

Page 74 #’s 1-5 1. Define each of the following: a. atom b. electron c. nucleus d. proton e. neutron a. the smallest piece of an element that is still that element b. a negative part of the atom which give the atom its volume c. the positively charged, extremely dense center part of an atom that contains nearly all the atom's mass but takes up a extremely small part of its volume d. the subatomic particle that has a positive charge equal (in size) to the negative charge of an electron; found in the nucleus e. the electrically neutral subatomic particle found in atomic nuclei 2. Describe one conclusion made by each of the following scientists that led to the development of the current atomic theory: a. Thomson b. Millikan c. Rutherford a. concluded that all atoms have charged parts some positive, some negative b. confirmed the negative charge of the electron and suggested the mass of an electron is ~ 1/2000 of the mass of a hydrogen atom c. determined that most of the mass of an atom is found in the nucleus and that the nucleus occupies very little space within an atom 3. Compare and contrast the three types of subatomic particles in terms of location in the atom, mass, and relative charge. Electrons surround the nucleus and have a negative charge and small mass relative to protons and neutrons Most of an atom's mass Is In its nucleus, which is near the center and is composed of protons and neutrons Protons have a positive charge; neutrons have no charge. -

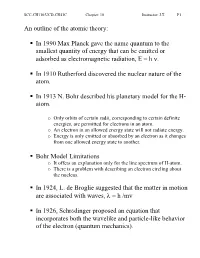

An Outline of the Atomic Theory

SCC-CH110/UCD-CH41C Chapter: 10 Instructor: J.T. P1 An outline of the atomic theory: In 1990 Max Planck gave the name quantum to the smallest quantity of energy that can be emitted or adsorbed as electromagnetic radiation, E = h ν. In 1910 Rutherford discovered the nuclear nature of the atom. In 1913 N. Bohr described his planetary model for the H- atom. o Only orbits of certain radii, corresponding to certain definite energies, are permitted for electrons in an atom. o An electron in an allowed energy state will not radiate energy. o Energy is only emitted or absorbed by an electron as it changes from one allowed energy state to another. Bohr Model Limitations o It offers an explanation only for the line spectrum of H-atom. o There is a problem with describing an electron circling about the nucleus. In 1924, L. de Broglie suggested that the matter in motion are associated with waves, λ = h /mv In 1926, Schrödinger proposed an equation that incorporates both the wavelike and particle-like behavior of the electron (quantum mechanics). SCC-CH110/UCD-CH41C Chapter: 10 Instructor: J.T. P2 Orbitals and quantum numbers: The solution to Schrödinger’s equation for the hydrogen atom yields a set of wave functions or orbitals. The Bohr model introduced a single atomic number n to describe an orbit. The quantum mechanical model uses n, l, and m to describe an orbital. Quantum Numbers: Symbol n Name Principal quantum number Values 1, 2, 3, .. description Defines the size of the orbital -18 2 Note For the Bohr model: En= - 2.18x10 J(1/n ) Symbol l Name Azimuthal quantum number Values From 0 to (n-1) Description Defines the shape of the orbital Note The value of l 0 1 2 3 Letter used s p d f Symbol m Name Magnetic quantum number Values From l to -l , including zero Description Defines the orientation of orbital in space -18 2 Note For the Bohr model: En= - 2.18x10 J(1/n ) i.e.: l=2 m: 2, 1, 0, -1, -2 SCC-CH110/UCD-CH41C Chapter: 10 Instructor: J.T. -

Matter and the Rise of Atomic Theory the Art of the Meticulous

UNIT 1 Matter and the Rise of Atomic Theory The Art of the Meticulous Unit Overview Since the first time early humans lit a fire and cooked food, people have been manipulating the matter around them. That’s what chemistry is – the manipulation of matter – and it has been performed since long before the word “chemistry” ever existed. Every person does chemistry every day, and not just the chemistry that is going on inside the human body. Ancient people became adept at manipulating materials with the goal of creating products to improve their lives. For example, they fired clay to make ceramics and mixed herbs to create medicines. Eventually, humans tried to create models and theories to explain why certain chemi- cal manipulations worked. This is the point at which chemistry became “a science.” Our goal in this first unit is to show how chemistry evolved from manipulating materials for practical purposes to Dalton’s first atomic theory of matter. It is a story that will start with Democritus around 400 BCE and go to the dawn of the 1800s, when modern scientific methods transformed the way people approached doing chemistry. Learning Objectives and Applicable Standards Participants will be able to: 1. Trace the origins of chemistry back to prehistoric times. 2. Understand the scientific method and the use of models in chemistry. 3. Define chemistry broadly as the accumulated knowledge, skills, methods, procedures, and theoretical framework that people use to manipulate matter to serve human needs. 4. Trace how phlogiston and other now-discredited chemical theories came to be replaced by a more scientific model of matter based on particles. -

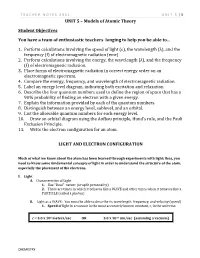

UNIT 5 – Models of Atomic Theory Student Objectives You Have A

TEACHER NOTES 2011 UNIT 5 | 1 UNIT 5 – Models of Atomic Theory Student Objectives You have a team of enthusiastic teachers longing to help you be able to… 1. Perform calculations involving the speed of light (c), the wavelength (λ), and the frequency (f) of electromagnetic radiation (emr) 2. Perform calculations involving the energy, the wavelength (λ), and the frequency (f) of electromagnetic radiation. 3. Place forms of electromagnetic radiation in correct energy order on an electromagnetic spectrum. 4. Compare the energy, frequency, and wavelength of electromagnetic radiation. 5. Label an energy level diagram, indicating both excitation and relaxation 6. Describe the four quantum numbers used to define the region of space that has a 90% probability of finding an electron with a given energy. 7. Explain the information provided by each of the quantum numbers. 8. Distinguish between an energy level, sublevel, and an orbital. 9. List the allowable quantum numbers for each energy level. 10. Draw an orbital diagram using the Aufbau principle, Hund’s rule, and the Pauli Exclusion Principle. 11. Write the electron configuration for an atom. LIGHT AND ELECTRON CONFIGURATION Much of what we know about the atom has been learned through experiments with light; thus, you need to know some fundamental concepts of light in order to understand the structure of the atom, especially the placement of the electrons. I. Light A. Characteristics of Light 1. Has "Dual" nature (or split personality) 2. There are times in which it behaves like a WAVE and other times when it behaves like a PARTICLE (called a photon) B. -

The Atomic Theory

The Atomic Theory The idea that the elements are capable of being split up into very tiny particles was first evolved by the Greeks. The word atom comes from the greek word atomos which means indivisible and the idea that the elements are made up of atoms is called the atomic theory. A scientific theory is a scientific idea which has been accepted by scientists after due consider- ation. When an idea is first proposed it is called a hypothesis (note. theories are not facts but thoughts). A scientific law is a generalised statement of observed facts. The Laws of Chemical Combination Lavoisier (1774) showed that when tin is made to react with air in a closed vessel the weight of the vessel before and after heating is the same. Law of Conservation of Mass: The mass of a system is not affected by any chemical change within the system. When various metals are oxidised one part by weight of oxygen always combines with the same number of parts by weight of the metal. Law of Definite Proportions: A particular chemical compound always con- tains the same elements united in the same proportions by weight. Two elements can also combine to form more than one compound. For example, the different weights of oxygen which can combine with the same weight of nitrogen are integral multiples of 8. Law of Multiple Proportions: If two elements combine to form more than one compound the different weights of one which combine with the same weight of the other are in the ration of small whole numbers. -

History of Atomic Theory Atomic Structure

NTI Day 4 Lesson Content Standard: Atomic Structure and Theory Class: Chemistry Teacher: K. Kelly History of Atomic Theory Modern atomic theory is rooted in the study of the structure of matter. Scientists for thousands of years have hypothesized about the makeup of matter. The time line below shows some important developments in scientific knowledge about matter and its building block, the atom. The Greek philosopher Democritus proposed that matter is composed of relatively simple c. 400 particles that are too small to be visible to the naked eye. These particles, which he called B.C. atoma (a Greek word meaning, "things that cannot be cut or divided"), could not be further broken down into smaller particles. early British scientist John Dalton proposes that atoms of different substances can be distinguished 1800s by their mass. British physicist Joseph Thomson performs an experiment that proves that atoms contain 1897 negatively charged particles-electrons. American researcher Robert Millikan experimented with drops of oil in order to calculate the 1901 mass of electrons. British chemist Ernest Rutherford proposed that an atom contained a nucleus, which was 1911 positively charged, dense, and very small. Rutherford is also credited with having discovered the proton in 1919. British physicist James Chadwick, building upon Rutherford's experiments, discovered that 1932 atomic nuclei contain neutrally charged particles-neutrons-in addition to protons. Today, the discoveries of Dalton, Thomson, Millikan, Rutherford, Chadwick, and many other scientists are combined to form the quantum mechanics atomic theory. Atomic Structure Matter is made of minute particles called atoms. An atom is the smallest part of an element that still retains properties of that element.