Vedic River Sarasvati Hindu Civilization

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

District Wise Skill Gap Study for the State of Haryana.Pdf

District wise skill gap study for the State of Haryana Contents 1 Report Structure 4 2 Acknowledgement 5 3 Study Objectives 6 4 Approach and Methodology 7 5 Growth of Human Capital in Haryana 16 6 Labour Force Distribution in the State 45 7 Estimated labour force composition in 2017 & 2022 48 8 Migration Situation in the State 51 9 Incremental Manpower Requirements 53 10 Human Resource Development 61 11 Skill Training through Government Endowments 69 12 Estimated Training Capacity Gap in Haryana 71 13 Youth Aspirations in Haryana 74 14 Institutional Challenges in Skill Development 78 15 Workforce Related Issues faced by the industry 80 16 Institutional Recommendations for Skill Development in the State 81 17 District Wise Skill Gap Assessment 87 17.1. Skill Gap Assessment of Ambala District 87 17.2. Skill Gap Assessment of Bhiwani District 101 17.3. Skill Gap Assessment of Fatehabad District 115 17.4. Skill Gap Assessment of Faridabad District 129 2 17.5. Skill Gap Assessment of Gurgaon District 143 17.6. Skill Gap Assessment of Hisar District 158 17.7. Skill Gap Assessment of Jhajjar District 172 17.8. Skill Gap Assessment of Jind District 186 17.9. Skill Gap Assessment of Kaithal District 199 17.10. Skill Gap Assessment of Karnal District 213 17.11. Skill Gap Assessment of Kurukshetra District 227 17.12. Skill Gap Assessment of Mahendragarh District 242 17.13. Skill Gap Assessment of Mewat District 255 17.14. Skill Gap Assessment of Palwal District 268 17.15. Skill Gap Assessment of Panchkula District 280 17.16. -

First Photographic Record of Cetti's Warbler Cettia Cetti

ABHINAV & SANGHA: Cetti’s Warbler 173 First photographic record of Cetti’s Warbler Cettia cetti from Himachal Pradesh, and a review of its status in India C. Abhinav & Harkirat Singh Sangha Abhinav, C., & Sangha H. S., 2019. First photographic record of Cetti’s Warbler Cettia cetti from Himachal Pradesh, and a review of its status in India. Indian BIRDS 14 (6): 173–176. C. Abhinav, Village & P.O. Ghurkari, Kangra 176001, Himachal Pradesh, India. E-mail: [email protected] [CA][Corresponding author] Harkirat Singh Sangha, B-27, Gautam Marg, Hanuman Nagar, Jaipur 302021 Rajasthan, India. E-mail: [email protected] [HSS] Manuscript received on 28 January 2018. etti’s Warbler Cettia cetti is a skulking, medium-sized, dull- coloured, short-winged, broad-tailed, un-streaked bush Cwarbler, and it frequently cocks its tail (Parmenter & Byers 1991). It breeds throughout the warmer regions of western and southern Europe, the Mediterranean islands, northern Africa to central Asia. The African and European populations are mainly resident but those breeding in colder western and central Asia migrate southwards. (Baker 1997; Kennerley & Pearson 2010). This note describes two recent sightings of the species in Himachal Pradesh, one previously unreported sighting from Badopal, Rajasthan, and assesses all reported records. On 02 October 2016, CA was at Sthana village, near Shah Nehar Barrage in Kangra District, Himachal Pradesh (31.96°N, 204. Habitat of Cetti’s Warbler near Jawalaji, Kangra District, Himachal Pradesh. 75.90°E; c. 325 m asl). There are many small ponds in this area, with an ample growth of Typha sp., and Ipomea sp. -

Secrets of RSS

Secrets of RSS DEMYSTIFYING THE SANGH (The Largest Indian NGO in the World) by Ratan Sharda © Ratan Sharda E-book of second edition released May, 2015 Ratan Sharda, Mumbai, India Email:[email protected]; [email protected] License Notes This ebook is licensed for your personal enjoyment only. This ebook may not be re-soldor given away to other people. If you would like to share this book with another person,please purchase an additional copy for each recipient. If you’re reading this book and didnot purchase it, or it was not purchased for your use only, then please return to yourfavorite ebook retailer and purchase your own copy. Thank you for respecting the hardwork of this author. About the Book Narendra Modi, the present Prime Minister of India, is a true blue RSS (Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh or National Volunteers Organization) swayamsevak or volunteer. More importantly, he is a product of prachaarak system, a unique institution of RSS. More than his election campaigns, his conduct after becoming the Prime Minister really tells us how a responsible RSS worker and prachaarak responds to any responsibility he is entrusted with. His rise is also illustrative example of submission by author in this book that RSS has been able to design a system that can create ‘extraordinary achievers out of ordinary people’. When the first edition of Secrets of RSS was released, air was thick with motivated propaganda about ‘Saffron terror’ and RSS was the favourite whipping boy as the face of ‘Hindu fascism’. Now as the second edition is ready for release, environment has transformed radically. -

District Survey Report for Sustainable Sand Mining Distt. Yamuna Nagar

DISTRICT SURVEY REPORT FOR SUSTAINABLE SAND MINING DISTT. YAMUNA NAGAR The Boulder, Gravel and Sand are one of the most important construction materials. These minerals are found deposited in river bed as well as adjoining areas. These aggregates of raw materials are used in the highest volume on earth after water. Therefore, it is the need of hour that mining of these aggregates should be carried out in a scientific and environment friendly manner. In an endeavour to achieve the same, District Survey Report, apropos “the Sustainable Sand Mining Guidelines” is being prepared to identify the areas of aggradations or deposition where mining can be allowed; and identification of areas of erosion and proximity to infrastructural structural and installations where mining should be prohibited and calculation of annual rate of replenishment and allowing time for replenishment after mining in that area. 1. Introduction:- Minor Mineral Deposits: 1.1 Yamunanagar district of Haryana is located in north-eastern part of Haryana State and lies between 29° 55' to 30° 31 North latitudes and 77° 00' to 77° 35' East longitudes. The total area is 1756 square kilometers, in which there are 655 villages, 10 towns, 4 tehsils and 2 sub-tehsils. Large part of the district of Yamunanagar is situated in the Shiwalik foothills. The area of Yamuna Nagar district is bounded by the state of Himachal Pradesh in the north, by the state of Uttar Pradesh in the east, in west by Ambala district and south by Karnal and Kurukshetra Districts. 1.2 The district has a sub-tropical continental monsoon climate where we find seasonal rhythm, hot summer, cool winter, unreliable rainfall and immense variation in temperature. -

Journal of Pharmaceutical and Scientific Innovation

Anuradha B et al: J. Pharm. Sci. Innov. 2019; 8(5) Journal of Pharmaceutical and Scientific Innovation www.jpsionline.com (ISSN : 2277 –4572) Research Article JIHWA PAREEKSHA IN SAAMA AVASTHA OF AMLAPITTA: A CLINICAL STUDY Anuradha B 1*, Ajantha 2, Anjana3, Geetha Nayak S 1 1Final year PG Scholar, Department of Roga Nidana & Vikruti Vignana, Sri Dharmasthala Manjunatheshwara College of Ayurveda and Hospital, Hassan, India 2Professor, Department of Roga Nidana & Vikruti Vignana, Sri Dharmasthala Manjunatheshwara College of Ayurveda and Hospital, Hassan, India 3Final year PG Scholar, Department of Swasthavritta & Yoga, Sri Dharmasthala Manjunatheshwara College of Ayurveda and Hospital, Hassan *Corresponding Author Email: [email protected] DOI: 10.7897/2277-4572.085149 Received on: 15/06/19 Revised on: 12/07/19 Accepted on: 17/07/19 ABSTRACT Ayurveda emphasizes agni-vaishamya as a cause of manifestation of vyadhi (disease). The undigested food due to vitiated agni results in apakwa-ahara-rasa, that does not get absorbed and transformed is termed as ama, is said to be root cause for diseases. Ama combines with dosha to form amadosha that acquires more shuktatva, further forming amavisha, paving to varied manifestations in diseases. Therefore, analyzing saama and niramavastha is essential for better diagnosis and management. Amlapitta, one among the annavaha-sroto-vikara manifests due to agni-vaishamya. Jihwa pareeksha (tongue examination) plays an important role to assess various changes in jihwa. It reflects the status of annavaha-srotas and ama. Thus, the present study aims at observation of manifestations on jihwa (tongue) by jihwa pareeksha in saama avastha of Amlapitta. Patients of Amlapitta were screened and subjected for jihwa pareeksha. -

Vaishvanara Vidya.Pdf

VVAAIISSHHVVAANNAARRAA VVIIDDYYAA by Swami Krishnananda The Divine Life Society Sivananda Ashram, Rishikesh, India (Internet Edition: For free distribution only) Website: www.swami-krishnananda.org CONTENTS Publishers’ Note 3 I. The Panchagni Vidya 4 The Course Of The Soul After Death 5 II. Vaishvanara, The Universal Self 26 The Heaven As The Head Of The Universal Self 28 The Sun As The Eye Of The Universal Self 29 Air As The Breath Of The Universal Self 30 Space As The Body Of The Universal Self 30 Water As The Lower Belly Of The Universal Self 31 The Earth As The Feet Of The Universal Self 31 III. The Self As The Universal Whole 32 Prana 35 Vyana 35 Apana 36 Samana 36 Udana 36 The Need For Knowledge Is Stressed 37 IV. Conclusion 39 Vaishvanara Vidya Vidya by by Swami Swami Krishnananda Krishnananda 21 PUBLISHERS’ NOTE The Vaishvanara Vidya is the famous doctrine of the Cosmic Meditation described in the Fifth Chapter of the Chhandogya Upanishad. It is proceeded by an enunciation of another process of meditation known as the Panchagni Vidya. Though the two sections form independent themes and one can be studied and practised without reference to the other, it is in fact held by exponents of the Upanishads that the Vaishvanara Vidya is the panacea prescribed for the ills of life consequent upon the transmigratory process to which individuals are subject, a theme which is the central point that issues from a consideration of the Panchagni Vidya. This work consists of the lectures delivered by the author on this subject, and herein are reproduced these expositions dilating upon the two doctrines mentioned. -

4055 Capital Outlay on Police

100 9 STATEMENT NO. 13-DETAILED STATEMENT OF Expenditure Heads(Capital Account) Nature of Expenditure 1 A. Capital Account of General Services- 4055 Capital Outlay on Police- 207 State Police- Construction- Police Station Office Building Schemes each costing Rs.one crore and less Total - 207 211 Police Housing- Construction- (i) Construction of 234 Constables Barracks in Policelines at Faridabad. (ii) Construction of Police Barracks in Police Station at Faridabad. (iii) Construction of Police Houses for Government Employees in General Pool at Hisar. (iv) Construction of Houses of Various Categories for H.A.P. at Madhuban . (v) Investment--Investment in Police Housing Corporation. (vi) Construction of Police Houses at Kurukshetra,Sonepat, and Sirsa. (vii) Other Schemes each costing Rs.one crore and less Total - 211 Total - 4055 4058 Capital Outlay on Stationery and Printing- 103 Government Presses- (i) Machinery and Equipments (ii) Printing and Stationery (iii) Extension of Government Press at Panchkula Total - 103 Total - 4058 4059 Capital Outlay on Public Works- 01 Office Buildings- 051 Construction- (i) Construction of Mini Secretariat at Fatehabad (ii) Construction of Mini Secretariat at Jhajjar (iii) Construction of Mini Secretariat at Panchkula (iv) Construction of Mini Secretariat at Yamuna Nagar (v) Construction of Mini Secretariat at Kaithal (vi) Construction of Mini Secretariat at Rewari (vii) Construction of Mini Secretariat at Faridabad (viii) Construction of Mini Secretariat at Bhiwani (ix) Construction of Mini Secretariat at Narnaul (x) Construction of Mini Secretariat at Jind (xi) Construction of Mini Secretariat at Sirsa (xii) Construction of Mini Secretariat at Hisar 101 CAPITAL EXPENDITURE DURING AND TO END OF THE YEAR 2008-2009 Expenditure during 2008-2009 Non-Plan Plan Centrally Sponsered Total Expenditure to Schemes(including end of 2008-2009 Central Plan Schemes) 23 4 5 6 (In thousands of rupees) . -

Indian Hieroglyphs

Indian hieroglyphs Indus script corpora, archaeo-metallurgy and Meluhha (Mleccha) Jules Bloch’s work on formation of the Marathi language (Bloch, Jules. 2008, Formation of the Marathi Language. (Reprint, Translation from French), New Delhi, Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN: 978-8120823228) has to be expanded further to provide for a study of evolution and formation of Indian languages in the Indian language union (sprachbund). The paper analyses the stages in the evolution of early writing systems which began with the evolution of counting in the ancient Near East. Providing an example from the Indian Hieroglyphs used in Indus Script as a writing system, a stage anterior to the stage of syllabic representation of sounds of a language, is identified. Unique geometric shapes required for tokens to categorize objects became too large to handle to abstract hundreds of categories of goods and metallurgical processes during the production of bronze-age goods. In such a situation, it became necessary to use glyphs which could distinctly identify, orthographically, specific descriptions of or cataloging of ores, alloys, and metallurgical processes. About 3500 BCE, Indus script as a writing system was developed to use hieroglyphs to represent the ‘spoken words’ identifying each of the goods and processes. A rebus method of representing similar sounding words of the lingua franca of the artisans was used in Indus script. This method is recognized and consistently applied for the lingua franca of the Indian sprachbund. That the ancient languages of India, constituted a sprachbund (or language union) is now recognized by many linguists. The sprachbund area is proximate to the area where most of the Indus script inscriptions were discovered, as documented in the corpora. -

S. No. Name of the Ayurveda Medical Colleges

S. NO. NAME OF THE AYURVEDA MEDICAL COLLEGES Dr. BRKR Govt Ayurvedic CollegeOpp. E.S.I Hospital, Erragadda 1. Hyderabad-500038 Andhra Pradesh Dr.NR Shastry Govt. Ayurvedic College, M.G.Road,Vijayawada-520002 2. Urban Mandal, Krishna District Andhra Pradesh Sri Venkateswara Ayurvedic College, 3. SVIMS Campus, Tirupati North-517507Andhra Pradesh Anantha Laxmi Govt. Ayurvedic College, Post Laxmipura, Labour Colony, 4. Tq. & Dist. Warangal-506013 Andhra Pradesh Government Ayurvedic College, Jalukbari, Distt-Kamrup (Metro), 5. Guwahati- 781014 Assam Government Ayurvedic College & Hospital 6. Kadam Kuan, Patna 800003 Bihar Swami Raghavendracharya Tridandi Ayurved Mahavidyalaya and 7. Chikitsalaya,Karjara Station, PO Manjhouli Via Wazirganj, Gaya-823001Bihar Shri Motisingh Jageshwari Ayurved College & Hospital 8. Bada Telpa, Chapra- 841301, Saran Bihar Nitishwar Ayurved Medical College & HospitalBawan Bigha, Kanhauli, 9. P.O. RamanaMuzzafarpur- 842002 Bihar Ayurved MahavidyalayaGhughari Tand, 10. Gaya- 823001 Bihar Dayanand Ayurvedic Medical College & HospitalSiwan- 841266 11. Bihar Shri Narayan Prasad Awathy Government Ayurved College G.E. Road, 12. Raipur- 492001 Chhatisgarh Rajiv Lochan Ayurved Medical CollegeVillage & Post- 13. ChandkhuriGunderdehi Road, Distt. Durg- 491221 Chhatisgarh Chhatisgarh Ayurved Medical CollegeG.E. Road, Village Manki, 14. Dist.-Rajnandgaon 491441 Chhatisgarh Shri Dhanwantry Ayurvedic College & Dabur Dhanwantry Hospital 15. Plot No.-M-688, Sector 46-B Chandigarh- 160017 Ayurved & Unani Tibbia College and HospitalAjmal Khan Road, Karol 16. Bagh New Delhi-110005 Chaudhary Brahm Prakesh Charak Ayurved Sansthan 17. Khera Dabur, Najafgarh, New Delhi-110073 Bharteeya Sanskrit Prabodhini, Gomantak Ayurveda Mahavidyalaya & Research Centre, Kamakshi Arogyadham Vajem, 18. Shiroda Tq. Ponda, Dist. North Goa-403103 Goa Govt. Akhandanand Ayurved College & Hospital 19. Lal Darvaja, Bhadra Ahmedabad- 380001 Gujarat J.S. -

Academic Course Prospectus for the Session 2012-13

PROSPECTUS 2012-13 With Application Form for Admission Secondary and Senior Secondary Courses fo|k/kue~loZ/kuaiz/kkue~ NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF OPEN SCHOOLING (An autonomous organisation under MHRD, Govt. of India) A-24-25, Institutional Area, Sector-62, NOIDA-201309 Website: www.nios.ac.in Learner Support Centre Toll Free No.: 1800 180 9393, E-mail: [email protected] NIOS: The Largest Open Schooling System in the World and an Examination Board of Government of India at par with CBSE/CISCE Reasons to Make National Institute of Open Schooling Your Choice 1. Freedom To Learn With a motto to 'reach out and reach all', NIOS follows the principle of freedom to learn i.e., what to learn, when to learn, how to learn and when to appear in the examination is decided by you. There is no restriction of time, place and pace of learning. 2. Flexibility The NIOS provides flexibility with respect to : • Choice of Subjects: You can choose subjects of your choice from the given list keeping in view the passing criteria. • Admission: You can take admission Online under various streams or through Study Centres at Secondary and Senior Secondary levels. • Examination: Public Examinations are held twice a year. Nine examination chances are offered in five years. You can take any examination during this period when you are well prepared and avail the facility of credit accumulation also. • On Demand Examination: You can also appear in the On-Demand Examination (ODES) of NIOS at Secondary and Senior Secondary levels at the Headquarter at NOIDA and All Regional Centres as and when you are ready for the examination after first public examination. -

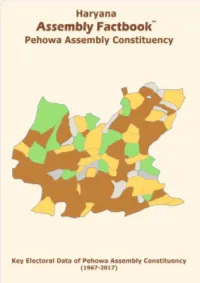

Pehowa Assembly Haryana Factbook | Key Electoral Data of Pehowa Assembly Constituency | Sample Book

Editor & Director Dr. R.K. Thukral Research Editor Dr. Shafeeq Rahman Compiled, Researched and Published by Datanet India Pvt. Ltd. D-100, 1st Floor, Okhla Industrial Area, Phase-I, New Delhi- 110020. Ph.: 91-11- 43580781, 26810964-65-66 Email : [email protected] Website : www.electionsinindia.com Online Book Store : www.datanetindia-ebooks.com Report No. : AFB/HR-14-0118 ISBN : 978-93-5293-531-4 First Edition : January, 2018 Third Updated Edition : June, 2019 Price : Rs. 11500/- US$ 310 © Datanet India Pvt. Ltd. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, mechanical photocopying, photographing, scanning, recording or otherwise without the prior written permission of the publisher. Please refer to Disclaimer at page no. 133 for the use of this publication. Printed in India No. Particulars Page No. Introduction 1 Assembly Constituency at a Glance | Features of Assembly as per 1-2 Delimitation Commission of India (2008) Location and Political Maps 2 Location Map | Boundaries of Assembly Constituency in District | Boundaries 3-9 of Assembly Constituency under Parliamentary Constituency | Town & Village-wise Winner Parties- 2014-PE, 2014-AE, 2009-PE and 2009-AE Administrative Setup 3 District | Sub-district | Towns | Villages | Inhabited Villages | Uninhabited 10-16 Villages | Village Panchayat | Intermediate Panchayat Demographics 4 Population | Households | Rural/Urban Population | Towns and Villages by 17-18 Population Size | Sex Ratio -

Flood Control Order- 2019

1 FLOOD CONTROL ORDER- 2019 DISTRICT, PANCHKULA 2 Flood Control Order-2013 (First Edition) Flood Control Order-2014 (Second Edition) Flood Control Order-2015 (Third Edition) Flood Control Order-2016 (Fourth Edition) Flood Control Order-2017 (Fifth Edition) Flood Control Order-2018 (Sixth Edition) Flood Control Order-2019 (Seventh Edition) 3 Preface Disaster is a sudden calamitous event bringing a great damage, loss,distraction and devastation to life and property. The damage caused by disaster is immeasurable and varies with the geographical location, and type of earth surface/degree of vulnerability. This influence is the mental, socio-economic-political and cultural state of affected area. Disaster may cause a serious destruction of functioning of society causing widespread human, material or environmental losses which executed the ability of affected society to cope using its own resources. Flood is one of the major and natural disaster that can affect millions of people, human habitations and has potential to destruct flora and fauna. The district administration is bestowed with the nodal responsibility of implementing a major portion of alldisaster management activities. The increasingly shifting paradigm from a reactive response orientation to a proactive prevention mechanism has put the pressure to build a fool-proof system, including, within its ambit, the components of the prevention, mitigation, rescue, relief and rehabilitation. Flood Control Order of today marks a shift from a mereresponse-based approach to a more comprehensive preparedness, response and recovery in order to negate or minimize the effects of severe forms of hazards by preparing battle. Keeping in view the nodal role of the District Administration in Disaster Management, a preparation of Flood Control Order is imperative.