Benchmarking for Best Practice: the Power of Its Adoption and the Perils of Ignoring Its Use in a Modern Business Environment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

22-24 August, 2018 Cardiff University, Wales, UK Conference Program

QMOD 21st International Conference on Quality and Service Sciences Conference Program 22-24 August, 2018 Cardiff University, Wales, UK 21st QMOD-ICQSS Conference The Quality Movement - where are we going? Past, Present, and Future Su Mi Dahlgaard-Park Dr. Professor Lund University Jens J. Dahlgaard Dr. Professor Linköping University The theme of the QMOD2018 conference invites participants to reflect on the evolution of total quality management (TQM) as the most widespread quality management approach during the last 30 years. Even though quality management approaches have been recognised and utilised by industry since the 1930s, the ‘arrival of TQM’ in the last part of the 1980s opened a new era in the quality movement. However, during the first 17 years of the new millennium, the term TQM seems to have lost its attractiveness in the industrialised parts of the world, and instead new terms such as Business Excellence, Organisational Excellence, Operational Excellence, Six Sigma, and Lean seem on the surface to have overtaken the leading position even though the contents of these new terms can and should be understood within the framework of TQM. Many practitioners perceive that these new terminologies are new management approaches which have replaced TQM and hence have little to do with quality approaches. Parallel with these tendencies, we can observe that the interest for TQM is growing in eastern European, some Asian countries (for example China) as well as in many new developing countries. There are, in those countries, numerous dynamic activities for learning, dissemination, promoting and implementing TQM. Also there is right now a growing interest to analyse and discuss the suitability of existing TQM frameworks in the 4th industrial revolution which will affect business environments – internal as well as external environments – including our living environments. -

Elements and Framework

Proceedings of the International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Operations Management Bangkok, Thailand, March 5-7, 2019 Excellent Performance Realization Methodologies (EPRMs): Elements and Framework Alaa M. Ubaid and Fikri T. Dweiri College of Engineering, University of Sharjah, University City, Sharjah, UAE [email protected], [email protected] Abstract Business excellence and excellent performance realization on organizational level has been attracting many researchers in the last two decades. Business Excellence models (BEMs) and their related methodological issues subjected as well to deep investigation. However, in the state of the art literature, it has been proved that BEMs still have some methodological issues that need to be resolved. In the current paper, as part of ongoing project to evaluate BEMs’ EPRMs efficiency and effectiveness, Excellence Performance Realization Methodologies (EPRM) terminologies analyzed, and then EPRM defined. Affinity diagram used to extract the necessary information from the reviewed literature, organize it, and remove the duplicated information in order to identify the main elements of EPRMs. Based on the conducted analysis, six elements of EPRMs proposed namely Equipment, Fundamentals, Performance management, Inputs, Process, and Outputs, then conceptual framework for applying EPRMs elements proposed. The proposed framework gives an insight, to the researchers and practitioners in organizational excellence scope, about the elements need to be exist in any model/methodology adopted -

Towards a Redefinition of Quality Management in Accordance with Islam1

International Journal for Innovation Education and Research www.ijier.net Vol:-3 No-11, 2015 Towards A Redefinition Of Quality Management In Accordance With Islam1 Fadzila Azni Ahmad2 Centre for Islamic Development Management Studies (ISDEV) Universiti Sains Malaysia, Penang, Malaysia E-mail: [email protected] Abstract This paper aims to discuss the need to redefine quality management in accordance with Islam by analysing the existing quality management definition from the Islamic philosophy perspective. The redefinition of quality management is an important contribution to the management of Islamic development institutions. Discussion towards the redefinition of quality management in this paper is based on theoretical analysis of the existing conventional quality management. This paper attempts to argue that the meaning of the existing conventional quality management is mainly limited to material and tangible aspects, such as commercialisation, increased revenues, competitiveness and meeting customer needs, whereas the philosophy and principles that underpin the development of Islamic institutions are unique and comprehensive compared to the limited material and tangible aspects. This paper proves there is a need to fill the gap in quality management of Islamic development institutions by coming up with a definition of quality management from the Islamic perspective. 1. Introduction The management of Islamic development institutions of today are more likely to adopt the conventional quality management such as the Total Quality Management -

International Quality Congress Preliminary Program – Issued June 16, 2021 First Day, June 29, 2021

International Quality Congress Preliminary Program – issued June 16, 2021 First day, June 29, 2021 Time Author Title of the paper 900 CONGRESS OPENING Dr. Jovo Lojanica, President Welcome words SRMEK Artistic program Torolf Paulshus, President Welcome words EOQ Quality Teaching in European Higher Education Dr. Paulo Sampaio Institutions “Enhancing Teaching Quality begins with Feedback of Dr. Noriaki Kano Test Results to the Class; A Case Study: Teaching the Life Cycle of Attractive Quality in Kano Model” 1030 PAUSE Joseph M. Juran's Universal Principles and Today's Dr. Joseph A. DeFeo Global Use Dr. Patricia A. Adam Practically best friends?! Agility and ISO 9001 WITH NEW QUALITY CONCEPTS TO FUTURE Beata Starzyńska, Agnieszka Virtual quality toolbox as an innovative solution supporting Kujawińska, Filip Górski, Paweł lifelong learning - Poland Buń Azat Abdrakhmanov Quality Kazakhstan Concept based on the Strategy "Kazakhstan-2050" - Kazakhstan Narayanan Ramanathan On Being a Quality Professional – India Renata Nováková Quality or quantity ? Harmonization of standards for evaluation of the quality of university education in the territory of the SR – Slovakia Noordhoek Peter Determining the added value of peer-based audits in associations through a semi-inductive approach – Netherlands 1200 PAUSE for lunch 1300 FUTURE OF QUALITY EDUCATION & TRAINING Vandenbrande Willy Integration: The Key To Effective And Efficient Quality Education – Belgium Grace Brannan; Thomas Educating Resident Physicians in Quality Improvement in the Alderson; James -

Total Quality Management Course Code: POM-324 Author: Dr

Subject: Total Quality Management Course Code: POM-324 Author: Dr. Vijender Pal Saini Lesson No.: 1 Vetter: Dr. Sanjay Tiwari Concepts of Quality, Total Quality and Total Quality Management Structure 1.0 Objectives 1.1 Introduction 1.2 Concept of Quality 1.3 Dimensions of Quality 1.4 Application / Usage of Quality for General Public / Consumers 1.5 Application of Quality for Producers or Manufacturers 1.6 Factors affecting Quality 1.7 Quality Management 1.8 Total Quality Management 1.9 Characteristics / Nature of TQM 1.10 The TQM Practices Followed by Multinational Companies 1.11 Summary 1.12 Keywords 1.13 Self Assessment Questions 1.14 References / Suggested Readings 1 1.0 Objectives After going through this lesson, you will be able to: Understand the concept of Quality in day-to-day life and business. Differentiate between Quality and Quality Management Elaborate the concept of Total Quality Management 1.1 Introduction Quality is a buzz word in our lives. When the customer is in market, he or she is knowingly or unknowingly very cautious about the quality of product or service. Imagine the last buying of any product or service, e.g., mobile purchased last time. You must have enquired about various features like RAM, Operating System, Processor, Size, Body Colour, Cover, etc. If any of the features is not available, you might have suddenly changed the brand or have decided not to purchase it. Remember, how our mothers buy fruits, vegetables or grocery items. They are buying fresh and look-wise firm fruits, vegetable and groceries. Simultaneously, they are very conscious about the price of the fruits, vegetable and groceries. -

10-12 December, 2018

Host & Sponsor Organisers: 10-12 December, 2018 A roadmap for excellence in organisational performance & nation building Venue: Jumeirah at Etihad Towers, Abu Dhabi. Registration includes full admission to the 3 days of the Congress. It includes access to the exhibition hall, lunches and refreshments during the Congress sessions. It also includes the Congress Gala Dinner on the evening of the 11th December. Register here. Sunday 9th December For GBN and APQO members only: Annual General Meeting. Global Benchmarking Network – 9.30am to 5.00pm APQO Core Council Meeting, 1.15pm to 5.30pm APQO-ADICOE-GBN Welcome Dinner, 7.00pm – 9.00pm Monday 10th December Global Organisational Excellence Congress, 8.30am to 5.00pm Tour of Abu Dhabi and meal, 6.30 – 9.30pm Tuesday 11th December Global Organisational Excellence Congress, 8.30am to 5.00pm Congress Gala Dinner, 7.00pm to 9.30pm Wednesday 12th December Global Organisational Excellence Congress, 8.30am to 3.15pm Thursday 13th & Friday 14th December Benchmarking for Excellence – Certification Course, 8.00am to 4.30pm Included Events: 24th Asia Pacific Quality Organisation International Conference 3rd ACE Team Awards Competition 18th Global Performance Excellence Award 12th International Benchmarking Conference 6th Global Benchmarking Awards 6th International Best Practice Competition 2nd Organisation-wide Innovation Award Sheikh Khalifa Excellence Award’s Best Practice Sharing Conference Partners: Congress Themes The Themes (T) referred to within the programme are as follows. T1 - Organisational -

Appendix B Key Economic Indicaros

Assessment Of Corporate Governance Practices In Jordan: An Empirical Investigation Item Type Thesis Authors Hendawi, Raed Diab Moh’d Rights <a rel="license" href="http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by-nc-nd/3.0/"><img alt="Creative Commons License" style="border-width:0" src="http://i.creativecommons.org/l/by- nc-nd/3.0/88x31.png" /></a><br />The University of Bradford theses are licenced under a <a rel="license" href="http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/">Creative Commons Licence</a>. Download date 29/09/2021 11:17:13 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10454/12980 University of Bradford eThesis This thesis is hosted in Bradford Scholars – The University of Bradford Open Access repository. Visit the repository for full metadata or to contact the repository team © University of Bradford. This work is licenced for reuse under a Creative Commons Licence. ASSESSMENT OF CORPORATE GOVERNANCE PRACTICES IN JORDAN: AN EMPIRICAL INVESTIGATION R.D.M.HENDAWI PHD 2013 Assessment Of Corporate Governance Practices In Jordan: An Empirical Investigation Raed Diab Moh’d HENDAWI Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Faculty of Management University of Bradford 2013 Abstract Raed Diab Moh’d Hendawi Assessment of Corporate Governance Practices in Jordan: An Empirical Investigation Keywords: Corporate Governance (CG), Critical Factors (CF), Best Practice (BP), Shareholders, Board of Directors (BOD), Organisation for Economic Co- operation and Development (OECD) Principles. Corporate Governance (CG) nowadays is on the agenda of most developed and developing countries, including Jordan, and is receiving considerable attention in the business world as well as in the area of academic research, which is an indication of its importance for business development and society as a whole. -

The Impact of Market and Corporate Governance Factors

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Bradford Scholars The University of Bradford Institutional Repository http://bradscholars.brad.ac.uk This work is made available online in accordance with publisher policies. Please refer to the repository record for this item and our Policy Document available from the repository home page for further information. To see the final version of this work please visit the publisher’s website. Access to the published online version may require a subscription. Link to publisher site: http://www.brad.ac.uk/acad/management/external/pdf/ workingpapers/2007/Booklet_07-06.pdf Citation: Li J, Pike RH and Haniffa RM (2007) Intellectual Capital Disclosure in Knowledge Rich Firms: The Impact of Market and Corporate Governance Factors. Bradford University School of Management Working Paper Series. No. 07/06. Copyright statement: © 2007 University of Bradford. Working Paper Series Intellectual Capital Disclosure in Knowledge Rich Firms: The Impact of Market and Corporate Governance Factors Jing Li Richard Pike Roszaini Haniffa Working Paper No 07/06 April 2007 The working papers are produced by the Bradford University School of Management and are to be circulated for discussion purposes only. Their contents should be considered to be preliminary. The papers are expected to be published in due course, in a revised form and should not be quoted without the author’s permission. WORKING PAPER SERIES INTELLECTUAL CAPITAL DISCLOSURE IN ABSTRACT KNOWLEDGE RICH FIRMS: THE IMPACT OF Intellectual capital disclosure (ICD) in corporate MARKET AND CORPORATE GOVERNANCE annual reports has received growing European FACTORS attention. -

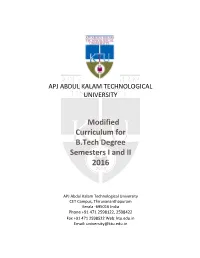

Modified Curriculum for B.Tech Degree Semesters I and II

APJ ABDUL KALAM TECHNOLOGICAL UNIVERSITY Modified Curriculum for B.Tech Degree Semesters I and II 2016 APJ Abdul Kalam Technological University CET Campus, Thiruvananthapuram Kerala -695016 India Phone +91 471 2598122, 2598422 Fax +91 471 2598522 Web: ktu.edu.in Email: [email protected] SEMESTER I Slot Course No. Subject L-T-P Hours Credits A MA101 Calculus 3-1-0 4 4 PH100 Engineering Physics 3-1-0 4 4 B (1/2) CY100 Engineering Chemistry 3-1-0 4 4 BE100 Engineering Mechanics 3-1-0 4 4 C (1/2) BE110 Engineering Graphics 1-1-3 5 3 D BE101-04 Introduction to Electronics Engineering 2-1-0 3 3 E BE103 Introduction to Sustainable Engineering 2-0-1 3 3 CE100 Basics of Civil Engineering 2-1-0 3 3 F ME100 Basics of Mechanical Engineering 2-1-0 3 3 EE100 Basics of Electrical Engineering 2-1-0 3 3 (1/4) EC100 Basics of Electronics Engineering 2-1-0 3 3 PH110 Engineering Physics Lab 0-0-2 2 1 S (1/2) CY110 Engineering Chemistry Lab 0-0-2 2 1 CE110/ME110/ 0-0-2 2 1 Basic Engineering Workshops T EE110/EC110/ + (CS110 for CS and related branches and (2/4) CH110 for CH and related branches only) CS110/CH110 0-0-2 2 1 U100 Language lab/CAD Practice/Bridge courses/Micro Projects etc U 0-0-(2/3) (2/3) 30 24/23 V100 Entrepreneurship/TBI/NCC/NSS/ Activity V 0-0-2 2 points Physical Edn. etc Notes: 1. -

The City University of New York University of Cairo, Faculty

Mohamed A. Youssef, Ph.D. Professor of Operations and Supply Chain Management HOME ADDRESSDepartment 1028 of ManageAutumnment Harvest and Marketing Drive, College of Industrial ManagementVirginia Beach, (AACSB VA, accredited) 23464 King Fahd University of Petroleum and Minerals P.O.USA. Box 1249 Tel. Dhahran(757) 495-2157. 31261 [email protected] Arabia Tel. + 966-3-860-4664 [email protected] EDUCATION The City University of New York Ph.D. in Business Administration Major: Management Planning Systems and Operations Management. Minor: Quantitative Methods and Statistics Dissertation: Advanced Manufacturing Technologies, Manufacturing Strategy, and Economic Performance: An Empirical Investigation. (Nominated for Lasdon Best Dissertation Award, Graduate School and University Center, City University of New York). M.Phil: Master of Philosophy in Business. MBA: Master of Business Administration. University of Cairo, Faculty of Commerce (Egypt) Prep. Study for Master of Business Administration. B.Com in Business Administration. HONORS ♦ Graduated with the merit of “Excellent” and top of the class (1973), Faculty of Commerce, University of Cairo. ♦ Inducted into Beta Gamma Sigma in 1988 as a Ph.D. student. ♦ My Doctoral dissertation was nominated for the Ladson best Dissertation Award, Graduate School and University Center, City University of New York (CUNY), 1991. ♦ Best applied research paper: "Technology Integration and Manufacturing Performance", International Academy of Business Disciplines, fourth annual meeting, April 1993. ♦ Ten best papers Award: "Competing in Global Markets on The Basis of Speed and Agility" , Academy of International Business, June 1993. ♦ Distinguished lecture series at Ithaca College for the Centennial year (1994). Lectured on “Competing in Global Markets: New trends in the 1990s.” ♦ Dana Research Fellow for 1994-1995: Sponsored by Dana Foundation and is awarded to an outstanding researcher on an annual basis. -

Bled | 11 and 12 October 2017) AFR PREMIUM ECO 210X300 3Mm 02 SI-EN PRESS.Pdf 1 26/09/2017 15:01:25

Special report: Slovenian Insight in association with S&P Global Ratings The Slovenia Times Slovenian Magazine in English Language Autumn Edition 2017, Volume 14, EUR 4.90 www.sloveniatimes.com Dr Sundeep Waslekar (India): Basketball Gold – 12th Bled Strategic Forum: OECD: Slovenia needs to boost "The world needs a preventive Lessons to learn Confronting the New Realities investment and productivity not a reactive approach" with New Strategies through better skills and regulation The 61st EOQ Congress: "Success in the digital era – Quality as a key driver" (Bled | 11 and 12 October 2017) AFR_PREMIUM_ECO_210x300_3mm_02_SI-EN_PRESS.pdf 1 26/09/2017 15:01:25 A PEACEFUL HAVEN Discover the intimacy of our Premium Economy cabin. AIRFRANCE.SI Editorial If all the numbers are to be believed, we can look forward to good times in Slovenia in the year ahead. In their Autumn forecast, IMAD have upgraded the forecast for 2017 GDP to 4.4%. Whether the positive numbers from Slovenia’s economy will be translated into better times for business is debatable. If we turn the clock back a decade, the confidence levels were Autumn Edition 2017 similar and very quickly the benefits were squan- www.sloveniatimes.com dered. There are often parallels made between sporting teams and business success and maybe we should look Published quarterly by Domus, založba in trgovina d.o.o. behind the success of our gold medal basketball team. Bregarjeva 37, 1000 Ljubljana, Slovenia Under the leadership of a (foreign) coach, a bunch of talented individuals came together to achieve what has been said is the biggest Editorial office success for Slovenian sport since independence. -

CSR: a Fresh Perspective and an Integrated Proposed Model

CSR: A Fresh Perspective and An Integrated Proposed Model By Professor Mohamed Zairi Juran Chair in TQM Director of ECTQM University of Bradford UK [email protected] Abstract Purpose: As the debate on the merits and de‐merits of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) rages on, it is clear that the existing business mindset has changed and the acceptance of a wider range of responsibilities for business is becoming more prevalent as a practice. There are pretentious arguments but also contentious issues that cannot be ignored in relation to CSR. The purpose of this paper is to examine the various schools of thought on CSR, to examine the arguments and logics presented and to try and enrich the current debate by presenting a new perspective. Methodology/Approach Through case study analysis, the paper focuses on the practices of two organisations often quoted as pioneers in CSR and examines the effectiveness of the models used by both BP and Starbucks. Findings The analysis of the two case studies involved has highlighted that CSR is a key driving force for modern competitiveness and acts as a catalyst for creating a competitive advantage. Originality: This paper presents a fresh perspective which supports the notion that CSR has to make good business sense and the way to do so is have an integrated business perspective. Inspired by a description of CSR as “an exploratory journey towards the identification and creation of common benefits which demands commitment, co‐operation and clear‐sightedness from all involved” (Holme and Watts, 2000), the proposed model has been put together.