Background Paper

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Victorian Support for Carers Program Providers

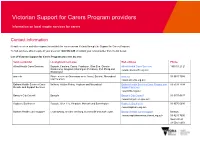

Victorian Support for Carers Program providers Information on local respite services for carers Contact information Respite services and other support is available for carers across Victoria through the Support for Carers Program. To find out more about respite in your area call 1800 514 845 or contact your local provider from the list below. List of Victorian Support for Carers Program providers by area Service provider Local government area Web address Phone Alfred Health Carer Services Bayside, Cardinia, Casey, Frankston, Glen Eira, Greater Alfred Health Carer Services 1800 51 21 21 Dandenong, Kingston, Mornington Peninsula, Port Phillip and <www.carersouth.org.au> Stonnington annecto Phone service in Grampians area: Ararat, Ballarat, Moorabool annecto 03 9687 7066 and Horsham <www.annecto.org.au> Ballarat Health Services Carer Ballarat, Golden Plains, Hepburn and Moorabool Ballarat Health Services Carer Respite and 03 5333 7104 Respite and Support Services Support Services <www.bhs.org.au> Banyule City Council Banyule Banyule City Council 03 9457-9837 <www.banyule.vic.gov.au> Baptcare Southaven Bayside, Glen Eira, Kingston, Monash and Stonnington Baptcare Southaven 03 9576 6600 <www.baptcare.org.au> Barwon Health Carer Support Colac-Otway, Greater Geelong, Queenscliff and Surf Coast Barwon Health Carer Support Barwon: <www.respitebarwonsouthwest.org.au> 03 4215 7600 South West: 03 5564 6054 Service provider Local government area Web address Phone Bass Coast Shire Council Bass Coast Bass Coast Shire Council 1300 226 278 <www.basscoast.vic.gov.au> -

CITY of MELBOURNE CREATIVE STRATEGY 2018–2028 Acknowledgement of Traditional Owners

CITY OF MELBOURNE CREATIVE STRATEGY 2018–2028 Acknowledgement of Traditional Owners The City of Melbourne respectfully acknowledges the Traditional Owners of the land, the Boon Wurrung and Woiwurrung (Wurundjeri) people of the Kulin Nation and pays respect to their Elders, past and present. For the Kulin Nation, Melbourne has always been an important meeting place for events of social, educational, sporting and cultural significance. Today we are proud to say that Melbourne is a significant gathering place for all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. melbourne.vic.gov.au CONTENTS Foreword 04 Context 05 Melbourne, a city that can’t stand still 05 How to thrive in a world of change 05 Our roadmap to a bold, inspirational future 05 Why creativity? Work, wandering and wellbeing 06 Case Studies 07 Düsseldorf Metro, Germany, 2016 09 Te Oro, New Zealand, 2015 11 Neighbour Doorknob Hanger 13 The Strategy 14 Appendices 16 Measuring creativity 17 How Melburnians contributed to this strategy 18 Melbourne’s Creative Strategy on a page 19 September 2018 Cover Image: SIBLING, Over Obelisk, part of Biennial Lab 2016. Photo by Bryony Jackson Image on left: Image: Circle by Naretha Williams performed at YIRRAMBOI Festival 2017. Photo Bryony Jackson Disclaimer This report is provided for information and it does not purport to be complete. While care has been taken to ensure the content in the report is accurate, we cannot guarantee is without flaw of any kind. There may be errors and omissions or it may not be wholly appropriate for your particular purposes. In addition, the publication is a snapshot in time based on historic information which is liable to change. -

Investigation Into Review of Parking Fines by the City of Melbourne

Investigation into review of parking fines by the City of Melbourne September 2020 Ordered to be published Victorian government printer Session 2018-20 P.P. No. 166 Accessibility If you would like to receive this publication in an alternative format, please call 9613 6222, using the National Relay Service on 133 677 if required, or email [email protected]. The Victorian Ombudsman pays respect to First Nations custodians of Country throughout Victoria. This respect is extended to their Elders past, present and emerging. We acknowledge their sovereignty was never ceded. Letter to the Legislative Council and the Legislative Assembly To The Honourable the President of the Legislative Council and The Honourable the Speaker of the Legislative Assembly Pursuant to sections 25 and 25AA of the Ombudsman Act 1973 (Vic), I present to Parliament my Investigation into review of parking fines by the City of Melbourne. Deborah Glass OBE Ombudsman 16 September 2020 2 www.ombudsman.vic.gov.au Contents Foreword 5 What motivated Council’s approach? 56 Alleged revenue raising – the evidence 56 Background 6 Poor understanding of administrative The protected disclosure complaint 6 law principles 59 Jurisdiction 6 Inflexible policies and lack of discretion 60 Methodology 6 Culture and resistance to feedback 62 Scope 7 What motivated these decisions? 63 Procedural fairness 7 Council’s response 63 City of Melbourne 8 Conclusions 65 The Branch 9 The conduct of individuals 65 Relevant staff 10 Final comment 65 Conduct standards for Council officers 10 -

VCHA 2018 All Entrants Book

Victorian Community History Awards 2018 List of Entries Presented by Public Record Office Victoria & Royal Historical Society of Victoria The Victorian Community History Awards recognise excellence in historical method: the award categories acknowledge that history can be told in a variety of formats with the aim of reaching and enriching all Victorians. the Victorian Community History Awards have been held since 1999, and are organised by the Royal Historical Society of Victoria in cooperation with Public Record Office Victoria. The 2018 Victorian Community History Awards is on the 8th October at the Arts Centre. This is a list of all the entries in the 2018 Victorian Community History Awards. The descriptions of the works are those provided by the entrants and are reproduced with their permission. Every attempt has been made to present these entries correctly and apologies are made for any errors or omissions. Some entrants have their publications for sale through the Royal Historical Society of Victoria Bookshop located at the below street and online addresses. For enquiries about the 2019 Awards contact RHSV on (03) 9326 9288. Entry forms will be available to download from www.historyvictoria.org.au in April 2019. Public Record Office Victoria Royal Historical Society of Victoria 99 Shiel St 239 A’Beckett St North Melbourne Melbourne www.prov.vic.gov.au www.historyvictoria.org.au @PublicRecordOfficeVictoria @historyvictoria @PRO_Vic @historyvictoria @vic_archives @historyvictoria Categories The Victorian Premier’s History Award recognises the most outstanding community history project in any category. The Collaborative Community History Award recognises the best collaborative community work involving significant contributions from individuals, groups, or historical societies. -

Proposed Determination of Allowances for Mayors, Deputy Mayors and Councillors

Proposed Determination of allowances for Mayors, Deputy Mayors and Councillors Consultation paper July 2021 1 Contents Contents ................................................................................................................................... 2 Abbreviations and glossary ........................................................................................................ 3 1 Introduction ...................................................................................................................... 5 2 Call for submissions ........................................................................................................... 7 3 Scope of the Determination ............................................................................................... 9 4 The Tribunal’s proposed approach ................................................................................... 10 5 Overview of roles of Councils and Council members......................................................... 11 Role and responsibilities of Mayors ..................................................................................... 13 Role and responsibilities of Deputy Mayors ........................................................................ 15 Role and responsibilities of Councillors ............................................................................... 15 Time commitment of Council role ....................................................................................... 16 Other impacts of Council role ............................................................................................. -

Application of Connectivity Modelling to Fragmented Landscapes at Local Scales

Application of connectivity modelling to fragmented landscapes at local scales Austin J. O Malley1 & Alex M. Lechner2 1 Eco Logical Australia – A Tetra Tech Company, 436 Johnston Street, Abbotsford, VIC 3067 E: [email protected] 2 School of Environmental and Geographical Sciences, University of Nottingham Malaysia Campus, 43500 Semenyih, Selangor, Malaysia E: [email protected] Multispecies connectivity modelling for conservation planning • Understanding habitat connectivity an essential requirement for effective conservation of wildlife populations • Used by planners and wildlife managers to address complex questions relating to the movement of wildlife • “What is the most effective design of a wildlife connectivity network for a particular species or suite of species”? • Important consideration in the management of road networks to avoid barriers between wildlife populations and reduce collisions • Estimating ecological connectivity at landscape scales is a complex task aided by the application of ecological models • Relatively underutilised in Australia, however, commonly used internationally in both planning and academia Connectivity Modelling and GAP CLoSR • Connectivity modelling has advanced rapidly in the last decade with improved computing power and more mainstream take-up of modelling tools in planning • Suite of modelling tools available to answer different questions (Circuitscape, Graphab, Linkage Mapper) • Recently integrated into a single decision-framework and software interface called GAP-CloSR1 • -

Victoria Harbour Docklands Conservation Management

VICTORIA HARBOUR DOCKLANDS CONSERVATION MANAGEMENT PLAN VICTORIA HARBOUR DOCKLANDS Conservation Management Plan Prepared for Places Victoria & City of Melbourne June 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES v ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS xi PROJECT TEAM xii 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 Background and brief 1 1.2 Melbourne Docklands 1 1.3 Master planning & development 2 1.4 Heritage status 2 1.5 Location 2 1.6 Methodology 2 1.7 Report content 4 1.7.1 Management and development 4 1.7.2 Background and contextual history 4 1.7.3 Physical survey and analysis 4 1.7.4 Heritage significance 4 1.7.5 Conservation policy and strategy 5 1.8 Sources 5 1.9 Historic images and documents 5 2.0 MANAGEMENT 7 2.1 Introduction 7 2.2 Management responsibilities 7 2.2.1 Management history 7 2.2.2 Current management arrangements 7 2.3 Heritage controls 10 2.3.1 Victorian Heritage Register 10 2.3.2 Victorian Heritage Inventory 10 2.3.3 Melbourne Planning Scheme 12 2.3.4 National Trust of Australia (Victoria) 12 2.4 Heritage approvals & statutory obligations 12 2.4.1 Where permits are required 12 2.4.2 Permit exemptions and minor works 12 2.4.3 Heritage Victoria permit process and requirements 13 2.4.4 Heritage impacts 14 2.4.5 Project planning and timing 14 2.4.6 Appeals 15 LOVELL CHEN i 3.0 HISTORY 17 3.1 Introduction 17 3.2 Pre-contact history 17 3.3 Early European occupation 17 3.4 Early Melbourne shipping and port activity 18 3.5 Railways development and expansion 20 3.6 Victoria Dock 21 3.6.1 Planning the dock 21 3.6.2 Constructing the dock 22 3.6.3 West Melbourne Dock opens -

Transporting Melbourne's Recovery

Transporting Melbourne’s Recovery Immediate policy actions to get Melbourne moving January 2021 Executive Summary The COVID-19 pandemic has impacted how Victorians make decisions for when, where and how they travel. Lockdown periods significantly reduced travel around metropolitan Melbourne and regional Victoria due to travel restrictions and work-from-home directives. As Victoria enters the recovery phase towards a COVID Normal, our research suggests that these travel patterns will shift again – bringing about new transport challenges. Prior to the pandemic, the transport network was struggling to meet demand with congested roads and crowded public transport services. The recovery phase adds additional complexity to managing the network, as the Victorian Government will need to balance competing objectives such as transmission risks, congestion and stimulating greater economic activity. Governments across the world are working rapidly to understand how to cater for the shifting transport demands of their cities – specifically, a disruption to entire transport systems that were not designed with such health and biosecurity challenges in mind. Infrastructure Victoria’s research is intended to assist the Victorian Government in making short-term policy decisions to balance the safety and performance of the transport system with economic recovery. The research is also designed to inform decision-making by industry and businesses as their workforces return to a COVID Normal. It focuses on how the transport network may handle returning demand and provides options to overcome the crowding and congestion effects, while also balancing the health risks posed by potential local transmission of the virus. Balancing these impacts is critical to fostering confidence in public transport travel, thereby underpinning and sustaining Melbourne’s economic recovery. -

Yana Ngargna Plan 2020-2023

Yarra City Council’s Yana Ngargna Plan 2020–2023 Yarra City Council’s Yana Ngargna1 Plan 2020–2023 A partnership with Wurundjeri Woi Wurrung, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities Yarra City Council acknowledges the Wurundjeri Woi Wurrung people as the Traditional Owners and true sovereigns of the land now known as Yarra. We acknowledge their creator spirit Bunjil, their ancestors and their Elders. We acknowledge the strength and resilience of the Wurundjeri Woi Wurrung, who have never ceded sovereignty and retain their strong connections to family, clan and country despite the impacts of European invasion. We also acknowledge the significant contributions made by other Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people to life in Yarra. We pay our respects to Elders from all nations here today— and to their Elders past, present and future. 1 Yana Ngargna means ‘continuing connection’ in Woi Wurrung language. 1 Yarra City Council’s Yana Ngargna Plan 2020–2023 Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................. 3 An Important Note on Terminology ............................................................................................. 4 Highlights from Previous Plans .................................................................................................... 6 Welcome to Country Ceremony — background information and protocol .................................. 6 Acknowledgement of Country—important background information -

Moreland City Council Affordable Housing Strategy 2014–2018

MORELAND CITY COUNCIL AFFORDABLE HOUSING STRATEGY 2014–2018 MORELAND CITY COUNCIL 1 MORELAND AFFORDABLE HOUSING STRATEGY 2014–2018 CONTENTS Foreword by the Mayor 03 Section 01: Introduction 04 Section 02: Principles and objectives 08 Section 03: Key definitions 12 Section 04: Council’s affordable housing work history 2001–2013 16 Section 05: Housing in Moreland: Tenure and affordability 18 Section 06: Policy context 30 Section 07: Challenges and considerations 32 Section 08: Implementation resources 36 Section 09: Implementation plan 39 Section 10: References 48 Appendix 01: Consultation and advice informing the Moreland Affordable Housing Strategy 2014–2018 49 Cover clockwise from top: Coburg ‘The Nicholson’, Places Victoria, Nation Building project, mixed tenure; Brunswick, public housing seniors; Coburg, community housing, Council partnership with Yarra Community Housing MORELAND CITY COUNCIL 01 The gentrification of parts of Moreland have put enormous pressure on low and fixed income earners and their ability to continue to live in the area. Source: Moreland Affordable Housing profile 2013 Above: Pascoe Vale, Housing Choices Australia, Nation Building project 02 MORELAND AFFORDABLE HOUSING STRATEGY 2014–2018 FOREWORD BY THE MAYOR The Moreland Affordable Housing Strategy (MAHS) 2014–2018 aims to maximise the supply of affordable housing in the municipality. Council recognises that many residents are The Council Plan 2013–2017 includes a key experiencing problems with housing affordability, strategy to ‘Support the improvement of and that affordability is an issue across all affordable housing options to accommodate the tenure groups. diverse Moreland community’. Council’s Priority Advocacy Program 2013–2014 identifies the The ‘great Australian dream’ of owning a home is urgent need to ‘Advocate to State Government quickly slipping away along with the traditional for increased investment in public and affordable ‘housing career’ experienced by previous generations. -

Protocol for Responding to Rough Sleeping, Squatting and Related Issues

City of Yarra Municipality Map Published by Yarra City Council © 2013 Community & Corporate Planning, Yarra City Council Post: PO Box 168 Richmond 3121 Telephone (03) 9205 5555 Yarra TTY (Telephone Typewriter) Number: 9421 4192 National Relay Service: 133 677 Yarralink (for people who do not speak English): 9280 1940 Email: [email protected] DISCLAIMER While all due care and good faith has been taken to ensure that the content of this publication is accurate and current, Yarra City Council does not accept any liability to any person or organisation arising from the information or opinions (or the use of such information and opinion) provided in this publication. Before relying on the material users should carefully evaluate the accuracy, currency and relevance for their purposes. Sources for the material used are duly quoted. Contents 1. Executive Summary .......................................................................................................... 1 2. Background ....................................................................................................................... 5 3. Discussion Paper Findings ................................................................................................. 9 3.1. Footpath congestion .................................................................................................. 9 3.2. Public transport, dedicated buses and taxi ranks .................................................... 10 3.3. Public toilets ............................................................................................................ -

VICTORIA Royal Botanic Gardens, Melbourne Royal

VICTORIA Royal Botanic Gardens, Melbourne Royal WHERE SHOULD ALL THE TREES GO? STATE BY STATE VIC WHAT’S HAPPENING? There has been an In VIC, 44% of urban LGAs have overall increase of undergone a significant loss of tree canopy, Average canopy cover for urban VIC is 3% in hard with only 8% having had a significant surfaces, which is increase in shrubbery. 18.83% exactly the same down 2.06% from rate of increase as NSW, but overall 20.89% VIC has around in 2013. 5% less hard surfaces than NSW. THERE HAVE BEEN QUITE A FEW SIGNIFICANT CANOPY LOSSES. – Notably in the City of Ballarat (5%), Banyule City Council (4.6%), Cardinia Shire Council (5.9%), Nillumbik Shire Council (12.8%), Maroondah City Council (4.7%), Mornington Peninsula Shire (4.7%) and Eira City Council (4.8%). WHERE SHOULD ALL THE TREES GO? VICTORIA VIC THE MOST & LEAST VULNERABLE 2.5 Rating Glen Eira City Council, Kingston City 3.0 Rating Council, City of Stonnington 2.0 Rating City of Port Phillip, Maroondah City Council, Moonee Valley City Council, Whittlesea City of Casey, Banyule City Council Council, Wyndham City Council 3.5 Rating 1.5 Rating City of Boroondara, City of Monash, Mornington Peninsula Shire, Frankston City Council, City of Greater Bendigo, City of Greater Dandenong, Cardinia Shire Council, City of Melbourne City of Greater Geelong, Hobsons Bay City Council, City of Melton 1.0 Rating 4.0 Rating City of Brimbank, Maribyrnong City Council, Yarra City Council, City of Whitehorse, Manningham City Council Moreland City Council 4.5 Rating Yarra Ranges Council,