The Logic of Sex

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Powell Mountain Karst Preserve: Biological Inventory of Vegetation Communities, Vascular Plants, and Selected Animal Groups

Powell Mountain Karst Preserve: Biological Inventory of Vegetation Communities, Vascular Plants, and Selected Animal Groups Final Report Prepared by: Christopher S. Hobson For: The Cave Conservancy of the Virginias Date: 15 April 2010 This report may be cited as follows: Hobson, C.S. 2010. Powell Mountain Karst Preserve: Biological Inventory of Vegetation Communities, Vascular Plants, and Selected Animal Groups. Natural Heritage Technical Report 10-12. Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation, Division of Natural Heritage, Richmond, Virginia. Unpublished report submitted to The Cave Conservancy of the Virginias. April 2010. 30 pages plus appendices. COMMONWEALTH of VIRGINIA Biological Inventory of Vegetation Communities, Vascular Plants, and Selected Animal Groups Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation Division of Natural Heritage Natural Heritage Technical Report 10-12 April 2010 Contents List of Tables......................................................................................................................... ii List of Figures........................................................................................................................ iii Introduction............................................................................................................................ 1 Geology.................................................................................................................................. 2 Explanation of the Natural Heritage Ranking System.......................................................... -

Fleas Are Parasitic Scorpionflies

Palaeoentomology 003 (6): 641–653 ISSN 2624-2826 (print edition) https://www.mapress.com/j/pe/ PALAEOENTOMOLOGY PE Copyright © 2020 Magnolia Press Article ISSN 2624-2834 (online edition) https://doi.org/10.11646/palaeoentomology.3.6.16 http://zoobank.org/urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:9B7B23CF-5A1E-44EB-A1D4-59DDBF321938 Fleas are parasitic scorpionflies ERIK TIHELKA1, MATTIA GIACOMELLI1, 2, DI-YING HUANG3, DAVIDE PISANI1, 2, PHILIP C. J. DONOGHUE1 & CHEN-YANG CAI3, 1, * 1School of Earth Sciences University of Bristol, Life Sciences Building, Tyndall Avenue, Bristol, BS8 1TQ, UK 2School of Life Sciences University of Bristol, Life Sciences Building, Tyndall Avenue, Bristol, BS8 1TQ, UK 3State Key Laboratory of Palaeobiology and Stratigraphy, Nanjing Institute of Geology and Palaeontology, and Centre for Excellence in Life and Paleoenvironment, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Nanjing 210008, China [email protected]; https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5048-5355 [email protected]; https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0554-3704 [email protected]; https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5637-4867 [email protected]; https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0949-6682 [email protected]; https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3116-7463 [email protected]; https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9283-8323 *Corresponding author Abstract bizarre bodyplans and modes of life among insects (Lewis, 1998). Flea monophyly is strongly supported by siphonate Fleas (Siphonaptera) are medically important blood-feeding mouthparts formed from the laciniae and labrum, strongly insects responsible for spreading pathogens such as plague, murine typhus, and myxomatosis. The peculiar morphology reduced eyes, laterally compressed wingless body, of fleas resulting from their specialised ectoparasitic and hind legs adapted for jumping (Beutel et al., 2013; lifestyle has meant that the phylogenetic position of this Medvedev, 2017). -

Evolution of Nuptial Gifts and Its Coevolutionary Dynamics With

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.06.22.165837; this version posted June 23, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. 1 Evolution of nuptial gifts and its coevolutionary dynamics with 2 "masculine" female traits for multiple mating 3 4 Yoshitaka KAMIMURA1*, Kazunori YOSHIZAWA2, Charles LIENHARD3, 5 Rodrigo L. FERREIRA4, and Jun ABE5 6 7 1 Department of Biology, Keio University, Yokohama 223-8521, Japan. 8 2 Systematic Entomology, School of Agriculture, Hokkaido University, Sapporo 060- 9 8589, Japan. 10 3 Geneva Natural History Museum, CP 6434, CH-1211 Geneva 6, Switzerland. 11 4 Biology Department, Federal University of Lavras, CEP 37200-000 Lavras (MG), 12 Brazil. 13 5 Faculty of Liberal Arts, Meijigakuin University, Yokohama, Japan 14 15 Correspondence: Yoshitaka Kamimura, Department of Biology, Keio University, 16 Yokohama 223-8521, Japan. 17 Email: [email protected] 18 19 Short title: Trading between male nuptial gifts and female multiple mating 20 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.06.22.165837; this version posted June 23, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. 21 ABSTRACT 22 Many male animals donate nutritive materials during courtship or mating to their female 23 mates. Donation of large-sized gifts, though costly to prepare, can result in increased 24 sperm transfer during mating and delayed remating of the females, resulting in a higher 25 paternity Nuptial gifting sometimes causes severe female-female competition for 26 obtaining gifts (i.e., sex-role reversal in mate competition) and female polyandry, 27 changing the intensity of sperm competition and the resultant paternity gains. -

Sue's Pdf Quark Setting

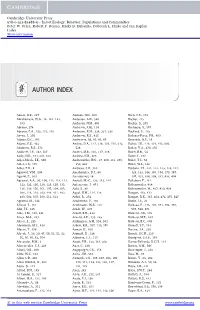

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-83488-9 - Insect Ecology: Behavior, Populations and Communities Peter W. Price, Robert F. Denno, Micky D. Eubanks, Deborah L. Finke and Ian Kaplan Index More information AUTHOR INDEX Aanen, D.K., 227 Amman, G.D., 600 Bach, C.E., 152 Abrahamson, W.G., 16, 161, 162, Andersen, A.N., 580 Bacher, 275 165 Andersen, N.M., 401 Bacher, S., 275 Abrams, 274 Anderson, J.M., 114 Bachman, S., 567 Abrams, P.A., 195, 273, 276 Anderson, R.M., 336, 337, 338 Ba¨ckhed, F., 225 Acorn, J., 250 Anderson, R.S., 415 Badenes-Perez, F.R., 400 Adams, D.C., 203 Andersson, M., 82, 83, 87 Baerends, G.P., 29 Adams, E.S., 435 Andow, D.A., 127, 128, 179, 276, 513, Bailey, J.K., 426, 474, 475, 603 Adamson, R.S., 573 528 Bailey, V.A., 279, 356 Addicott, J.F., 242, 507 Andres, M.R., 116, 117, 118 Baker, R.R., 54 Addy, N.D., 574, 601, 602 Andrew, N.R., 566 Baker, I., 247 Adjei-Maafo, I.K., 530 Andrewartha, H.G., 27, 260, 261, 279, Baker, T.C., 53 Adler, L.S., 155 356, 404 Baker, W.L., 166 Adler, P.H., 8 Andrews, J.H., 310 Baldwin, I.T., 121, 122, 125, 126, 127, Agarwal, V.M., 506 Aneshansley, D.J., 48 129, 143, 144, 166, 174, 179, 187, Agnew, P., 369 Anonymous, 18 197, 201, 204, 208, 221, 492, 498 Agrawal, A.A., 99, 108, 114, 118, 121, Anstett, M.-C., 236, 243, 244 Ballabeni, P., 162 122, 125, 126, 128, 129, 130, 133, Antonovics, J., 471 Baltensweiler, 414 136, 139, 156, 161, 197, 204, 205, Aoki, S., 80 Baltensweiler, W., 407, 410, 424 208, 216, 219, 299, 444, 471, 492, Appel, H.M., 124, 128 Bangert, 465, 472 493, 502, 507, 509, 512, 513 -

Nonrandom Mating in Nicotiana Attenuata and the Paternal Influence on Seed Metabolomes and Pathogen Resistance Dissertation by M

Nonrandom mating in Nicotiana attenuata and the paternal influence on seed metabolomes and pathogen resistance Dissertation To Fulfill the Requirements for the Degree of „doctor rerum naturalium“ (Dr. rer. nat.) Submitted to the Council of the Faculty of Biology and Pharmacy of the Friedrich Schiller University Jena by M.Sc., Xiang Li born on 10th November, 1986 in Qingdao, Shandong, China 1. Gutachter: Prof. Dr. Ian T. Baldwin, Max Planck Institute for Chemical Ecology, Jena, Germany 2. Gutachter: Prof. Dr. Erika Kothe, Friedrich-Schiller-University, Jena, Germany 3. Gutachter: Associate Prof. Åsa Lankinen, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, Uppsala, Sweden Tag der öffentlichen Verteidigung: 26th. 09. 2018 Contents Contents Abbreviations ................................................................................................................................... III 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Sexual selection and its application in plants ......................................................................................... 1 1.2 Sexual selection in plants ........................................................................................................................ 2 1.3 Nonrandom mating among compatible donors in Nicotiana attenuata ................................................ 5 1.4 PT growth rates and stylar metabolites in nonrandom mating ............................................................. -

Cooley, J. R. 1999. Sexual Behavior in North American Cicadas of The

Sexual behavior in North American cicadas of the genera Magicicada and Okanagana by John Richard Cooley A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Biology) The University of Michigan 1999 Doctoral Committee: Professor Richard D. Alexander, Chairman Professor George Estabrook Professor Brian Hazlett Associate Professor Warren Holmes John R. Cooley © 1999 All Rights Reserved To my wife and family ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This work was supported in part by the Horace H. Rackham School of Graduate Studies, the Department of Biology, the Museum of Zoology (UMMZ), the Frank W. Ammerman Fund of the UMMZ Insect Division, and by Japan Television Workshop Co., LTD. I thank the owners and managers of our field sites for their patience and understanding: Alum Springs Young Life Camp, Rockbridge County, VA. Horsepen Lake State Wildlife Management Area, Buckingham County, VA. Siloam Springs State Park, Brown and Adams Counties, IL. Harold E. Alexander Wildlife Management Area, Sharp County, AR. M. Downs, Jr., Sharp County, AR. Richard D. Alexander, Washtenaw County, MI. The University of Michigan Biological Station, Cheboygan and Emmet Counties, MI. John Zyla of the Battle Creek Cypress Swamp Nature Center, Calvert County, MD provided tape recordings and detailed distributions of Magicicada in Maryland. Don Herren, Gene Kruse, and Bill McClain of the Illinois Department of Natural Resources, and Barry McArdle of the Arkansas State Game and Fish Commission helped obtain permission to work on state lands. Keiko Mori and Mitsuhito Saito provided funding and high quality photography for portions of the 1998 field season. Laura Krueger performed the measurements in Chapter 7. -

Ulsd732423 Td Ines Dias.Pdf

UNIVERSIDADE DE LISBOA FACULDADE DE CIÊNCIAS The role of conspecific social information on male mating decisions “Documento Definitivo” Doutoramento em Biologia Especialidade Etologia Inês Órfão Dias Tese orientada por: Professor Doutor Paulo Jorge Fonseca Doutora Susana Araújo Marreiro Varela Professora Doutora Anne Elizabeth Magurran Documento especialmente elaborado para a obtenção do grau de doutor 2018 UNIVERSIDADE DE LISBOA FACULDADE DE CIÊNCIAS The role of conspecific social information on male mating decisions Doutoramento em Biologia Especialidade Etologia Inês Órfão Dias Tese orientada por: Professor Doutor Paulo Jorge Fonseca Doutora Susana Araújo Marreiro Varela Professora Doutora Anne Elizabeth Magurran Júri: Presidente: ● Doutor Rui Manuel dos Santos Malhó, Professor Catedrático e Presidente do Departamento de Biologia Vegetal da Faculdade de Ciências da Universidade de Lisboa Vogais: ● Doutora Anne Elizabeth Magurran, Professor School of Biology da University of St Andrews (Orientadora) ● Doutor Paulo Jorge Gama Mota, Professor Associado Faculdade de Ciências e Tecnologia da Universidade de Coimbra ● Doutor Gonçalo Canelas Cardoso, Pós-Doutoramento CIBIO - Centro de Investigação em Biodiversidade e Recursos Genéticos da Universidade do Porto ● Doutor Manuel Eduardo dos Santos, Professor Associado ISPA - Instituto Universitário de Ciências Psicológicas, Sociais e da Vida ● Doutora Sara Newbery Raposo de Magalhães, Professora Auxiliar Faculdade de Ciências da Universidade de Lisboa ● Doutora Maria Clara Correia de Freitas Pessoa de Amorim, Professora Auxiliar Faculdade de Ciências da Universidade de Lisboa Documento especialmente elaborado para a obtenção do grau de doutor Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia (SFRH / BD / 90686 / 2012) 2018 This research was founded by Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia through a PhD grant (SFRH/BD/90686/2012). -

Bittacidae of Illinos

An Overview and Dichotomous Key to the Bittacidae (Insecta: Mecoptera) of Illinois Jimmie W. Griffiths ENY 6166 Fall 2008 Jimmie Griffiths – ENY 6166 Table of Contents List of Figures 1. Introduction 2. Morphology of Bittacidae 3. Life History and Behavior 4. Taxonomy and Diversity of the Bittacidae in Illinois 6. Key to the Bittacidae of Illinois 7. Species Descriptions Hylobittacus apicalis (Hagen, 1861) 8. Bittacus punctiger Westwood, 1846 9. Bittacus pilicornis Westwood, 1846 10. Bittacus occidentis Walker, 1853 11. Bittacus strigosus Hagen, 1861 12. Bittacus stigmaterus Say, 1823 13. Bittacus texanus Banks, 1908 14. Conclusions 15. References 16. Figures 18. 2 Jimmie Griffiths – ENY 6166 List of Figures Figure 1. Hylobittacus apicalis – position of wings at rest. Figure 2. Genus Bittacus – position of wings at rest. Figure 3. Forewing of Hylobittacus apicalis Figure 4. Forewing of Bittacus punctiger Figure 5. Forewing of Bittacus pilicornis Figure 6. Forewing of Bittacus occidentis Figure 7. Forewing of Bittacus strigosus Figure 8. Forewing of Bittacus stigmaterus Figure 9. Forewing of Bittacus texanus Figure 10. Male Ninth Tergum of Abdomen - Bittacus stigmaterus Figure 11. Male Ninth Tergum of Abdomen - Bittacus texanus 3 Jimmie Griffiths – ENY 6166 Introduction The insect order Mecoptera is a morphologically basal group of holometabolous insects represented by 600 extant species divided into 34 genera and 9 families (Dunford, 2008). Fossil Mecopterans first appeared in the Permian period and are represented by 400 species. These insects are an important evolutionary link in the evolution of Dipterans and Siphonapterans. Of the extant Mecopterans, 95% of species are represented by only two families. The Panorpidae are represented by 380 species, while the Bittacidae are represented by 180 (Grimaldi, 2006), however Krzeminski (2007) estimates extant Bittacid species at 270. -

Why Did a Female Penis Evolve in a Small Group of Cave Insects?

Title Why Did a Female Penis Evolve in a Small Group of Cave Insects? Author(s) Yoshizawa, Kazunori; Ferreira, Rodrigo L.; Lienhard, Charles; Kamimura, Yoshitaka Bioessays, 41(6), 1900005 Citation https://doi.org/10.1002/bies.201900005 Issue Date 2019-06 Doc URL http://hdl.handle.net/2115/78286 This is the peer reviewed version of the following article: Why Did a Female Penis Evolve in a Small Group of Cave Insects?; Bioessays 41(6), June 2019, which has been published in final form at Rights https://doi.org/10.1002/bies.201900005. This article may be used for non-commercial purposes in accordance with Wiley Terms and Conditions for Use of Self-Archived Versions. Type article (author version) File Information BioEssays.rev1.final.pdf Instructions for use Hokkaido University Collection of Scholarly and Academic Papers : HUSCAP BioEssays: Hypotheses Why did a female penis evolve in a small group of cave insects? Kazunori Yoshizawa, Rodrigo L Ferreira, Charles Lienhard and Yoshitaka Kamimura Assoc. Prof. K. Yoshizawa Systematic Entomology School of Agriculture Hokkaido University Sapporo 060-8589, Japan E-mail: [email protected] Prof. R. L. Ferreira Biology Department Federal University of Lavras CEP 37200-000 Lavras (MG), Brazil Dr. C. Lienhard Geneva Natural History Museum CP 6434, 1211 Geneva 6, Switzerland Assoc. Prof. Y. Kamimura Department of Biology Keio University Yokohama 223-8521, Japan E-mail: [email protected] Abstract The evolution of a female penis is an extremely rare event and is only known to have occurred in a tribe of small cave insects, Sensitibillini (Psocodea: Trogiomorpha: Prionoglarididae). -

Orthoptera: Tettigoniidae

The Evolution and Function of the Spermatophylax in Bushcrickets (Orthoptera: Tettigoniidae). Karim Vahed, B.Sc Thesis submitted to the University of Nottingham for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, January 1994. ".. and soon from the male's convulsive loins there is seen to issue, in painful labour, something monstrous and un heard of, as though the creature were expelling its entrails in a lump". J.ll.Fabre (1899). To my Father. Abstract In certain species of cricket and bushcricket (Orthoptera; Ensifera), the male transfers an elaborate spermatophore to the female at mating. This consists of a sperm-containing ampulla and an often substantial, sperm-free, gelatinous mass known as the spermatophylax. After mating, the female eats the spermatophylax before consuming the ampulla. The spermatophylax is particularly well developed in the bushcrickets (Tettigoniidae) and can contribute to a loss of as much as 40% of male body weigh at mating in some species. Recently, there has been considerable debate over the selective pressures responsible for the evolution and maintenance of the spermatophylax and other forms of nuptial feeding in insects. Two different, though not mutually exclusive, functions have been suggested for the spermatophylax: 1) nutrients from the spermatophylax may function to increase the weight and\or number of eggs laid by the female, i.e. may function as paternal investment; 2) the spermatophylax may function to prevent the female from eating the ampulla before complete ejaculate transfer, i.e. may be regarded as a form of mating effort. In this study, a comparative approach combined with laboratory manipulations were used in an attempt to elucidate the selective pressures responsible for the origin, evolutionary enlargement and maintenance (= function) of the spermatophylax in bushcrickets. -

SOME ASPECTS of the POPULATION ECOLOGY of the GRASSHOPPER ACRIDA CONICA FABRICIUS This Thesis Is Presented for the Degree Of

SOME ASPECTS OF THE POPULATION ECOLOGY OF THE GRASSHOPPER ACRIDA CONICA FABRICIUS This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of Murdoch Universi 1 9 8 5 Submitted by Michael Charles Calver B.Sc. (Hons) Murdoch I ! Under carefully controlled conditions of temperature, humidity, light and any other important variable, the experimental animal will do as it damn well pleases. - Harvard Law of Biological Experimentation FRONTISPIECE Dorsal view of adult female Acrida conica� Original drawing by Mr. Mike Bamford. DECLARATION I declare that this thesis is my own account of my research and has as its main content work which has not been submitted previously for a degree at any university. Michael C. Calver August 1985 i I I I TABLE OF CONTENTS PUBLICATIONS (i) ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS (ii) ABSTRACT .. (iii) LIST OF TABLES (vii) LIST OF FIGURES (xi) 1. INTRODUCTION - AN APPROACH TO POPULATION BIOLOGY 1 2. BASIC BIOLOGY 11 2.1 The genus Acrida 11 2.2 Growth and development 11 2.3 Colour patterns and colour change 13 2.4 Natural enemies 15 2.5 Study sites 15 3. POPULATION DYNAMICS 20 3.1 Introduction 20 3.2 Materials and methods 21 3.3 Results .. 40 3.4 Discussion 44 4. ANTI-PREDATOR DEFENCES 53 4.1 Introduction 53 4.2 Crypsis, distribution and anti-predator behaviour in the field 61 4.3 Background colour matching 73 5. ARTHROPOD PREDATORS 77 5.1 Introduction 77 5.2 Methods .. 78 5.3 Results and discussion .. 82 6. VERTEBRATE PREDATORS 6.1 Prey choice in the field 85 6.2 Prey choice in the laboratory 89 CONDITION, FECUNDITY AND DIET 7.1 Introduction . -

A Preliminary Annotated Checklist of Mississippi Mecoptera (Insecta) Bill P

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Center for Systematic Entomology, Gainesville, Insecta Mundi Florida 2016 A Preliminary Annotated Checklist of Mississippi Mecoptera (Insecta) Bill P. Stark Mississippi College, [email protected] Paul K. Lago University of Mississippi, [email protected] Audrey B. Harrison University of Mississippi, [email protected] William E. Smith Mississippi College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/insectamundi Part of the Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Commons, and the Entomology Commons Stark, Bill P.; Lago, Paul K.; Harrison, Audrey B.; and Smith, William E., "A Preliminary Annotated Checklist of Mississippi Mecoptera (Insecta)" (2016). Insecta Mundi. 977. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/insectamundi/977 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Center for Systematic Entomology, Gainesville, Florida at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Insecta Mundi by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. INSECTA MUNDI A Journal of World Insect Systematics 0469 A Preliminary Annotated Checklist of Mississippi Mecoptera (Insecta) Bill P. Stark Department of Biology Mississippi College Box 4045 Clinton, MS 39058 USA Paul K. Lago Department of Biology University of Mississippi 214 Shoemaker Hall University, MS 38677 USA Audrey B. Harrison Department of Biology University of Mississippi Shoemaker Hall University, MS, 38677 USA William E. Smith Department of Biology Mississippi College Box 4045 Clinton, MS 39058 USA Date of Issue: February 12, 2016 CENTER FOR SYSTEMATIC ENTOMOLOGY, INC., Gainesville, FL Bill P. Stark, Paul K. Lago, Audrey B. Harrison, and William E.