Great Fortunes of the Gilded Age

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

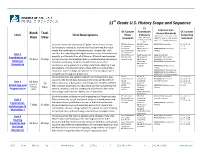

11 Grade U.S. History Scope and Sequence

th 11 Grade U.S. History Scope and Sequence C3 Common Core DC Content Framework DC Content Block Trad. Literacy Standards Unit Unit Descriptions Power Indicators RH.11-12.1, 11-12.2, 11-12.10 Supporting Days Days Standards D3.1, D4.3 and WHST.11-12.4, 11-12.5, 11-12.9 Standards D4.6 apply to each and 11-12.10 apply to each unit. unit. Students review the content of 8th grade United States History 11.1.6: Influences D1.4: Emerging RH.11-12.4: Vocabulary 11.1.1-11.1.5 on American questions 11.1.8 (colonization, revolution, and civil war) by examining the major Revolution D4.2: Construct WHST.11-12.2: Explanatory 11.1.10 trends from colonialism to Reconstruction. In particular, they 11.1.7: Formation explanations Writing of Constitution Unit 1 consider the expanding role of government, issues of freedom and 11.1.9: Effects of Apply to each unit: Apply to each unit: Foundations of equality, and the definition of citizenship. Students read complex Civil War and D3.1: Sources RH.11-12.1: Cite evidence 10 days 20 days primary sources, summarizing based on evidence while developing Reconstruction D4.3: Present RH.11-12.2: Central idea American historical vocabulary. Students should communicate their information RH.11-12.10: Comprehension D4.6: Analyze Democracy conclusions using explanatory writing, potentially adapting these problems WHST.11-12.4: Appropriate explanations into other formats to share within or outside their writing classroom. Students begin to examine the relationship between WHST.11-12.5: Writing process WHST.11-12.9: Using evidence compelling and supporting questions. -

American History 1 SSTH 033 061 Credits: 0.5 Units / 5 Hours / NCAA

UNIVERSITY OF NEBRASKA HIGH SCHOOL American History 1 SSTH 033 061 Credits: 0.5 units / 5 hours / NCAA Course Description This course discusses the development of America from the colonial era until the start of the twentieth century. This includes European exploration and the collision between different societies (including European, African, and Native American). The course also explores the formation of the American government and how democracy in the United States affected thought and culture. Students will also learn about the influences of the Enlightenment on different cultural groups, religion, political and philosophical writings. Finally, they will examine various reform efforts, the Civil War, and the effects of expansion, immigration, and urbanization on American society. Graded Assessments: 5 Unit Evaluations; 3 Projects; 3 Proctored Progress Tests; 5 Teacher Connect Activities Course Objectives When you have completed the materials in this course, you should be able to: 1. Identify the Native American societies that existed before 1492. 2. Explain the reasons for European exploration and colonization. 3. Describe the civilizations that existed in Africa during the Age of Exploration. 4. Explore how Europeans, Native Americans, and Africans interacted in colonial America. 5. Summarize the ideas of the Enlightenment and the Great Awakening. 6. Examine the reasons for the American Revolution. 7. Discuss how John Locke’s philosophy influenced the Declaration of Independence. 8. Understand how the American political system works. 9. Trace the development of American democracy from the colonial era through the Gilded Age. 10. Evaluate the development of agriculture in America from the colonial era through the Gilded Age. -

U.S. History Objectives

U.S. History Objectives Unit 1 An Age of Prosperity and Corruption Students will understand the internal growth of the United States during the period of 1850s-1900. • Identify the conditions that led to Industrial expansion. • Compare and contrast politics of the Gilded Age and today’s governmental systems. • Describe how immigration was changing the social landscape of the United States resulting in the need for reform. Analyze and interpret maps, tables, and charts. Identify key terms. The Expansion of American Industry 1850-1920 Students will understand the conditions that led to Industrial expansion. • Identify the conditions that led to Industrial expansion. • Describe the technological revolution and the impact of the railroads and inventions. • Explain the growth of labor unions and the methods used by workers to achieve reform. Politics, 1870-1915 Students will understand the changes in cities and politics during the period known as the Gilded Age. • Compare and contrast politics of the Gilded Age and today’s governmental systems. • Be able to communicate why American cities experienced rapid growth. • Summarize the growth of Big Business and the role of monopolies. Immigration and Urban Life, 1870-1915 Students will understand the impact of immigration on the social landscape of the United States. • Analyze and interpret maps, tables, and charts. • Identify key terms. Give examples of how immigration was changing the social landscape of the United States. Relate the reasons for reform and the impact of the social movement. Unit 2 Internal and External Role of the United States Students will describe the changing internal and external roles of the United States between 1890- 1920. -

Indigenous and Settler Violence During the Gilded Age and Progressive Era John R

Indigenous and Settler Violence during the Gilded Age and Progressive Era John R. Legg, George Mason University The absence of Indigenous historical perspectives creates a lacuna in the historiography of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era. For the first eight years of the Journal of the Gilded Age and the Progressive Era, zero articles written about or by Native Americans can be found within its pages. By 2010, however, a roundtable of leading Gilded Age and Progressive Era scholars critically examined the reasons why “Native Americans often slipped out of national consciousness by the Gilded Age and Progressive Era.”1 By 2015, the Journal offered a special issue on the importance of Indigenous histories during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, a “period of tremendous violence perpetuated on Indigenous communities,” wrote the editors Boyd Cothran and C. Joseph Genetin-Pilawa.2 It is the observation of Indigenous histories on the periphery of Gilded Age and Progressive Era that inspires a reevaluation of the historiographical contributions that highlight Indigenous survival through the onslaught of settler colonial violence during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The purpose of this microsyllabus seeks to challenge these past historiographical omissions by re-centering works that delve into the inclusion of Indigenous perspectives and experience of settler colonial violence during the Gilded Age and Progressive Era. Ultimately, this microsyllabus helps us unravel two streams of historiographical themes: physical violence and structural violence. Violence does not always have to be physical, but can manifest in different forms: oppression, limiting people’s rights, their access to legal representation, their dehumanization through exclusion and segregation, as well as the production of memory. -

The Politics of the Gilded Age

Unit 3 Class Notes- The Gilded Age The Politics of the Gilded Age The term “Gilded Age” was coined by Mark Twain in 1873 to describe the era in America following the Civil War; an era that from the outside looked to be a fantastic growth of wealth, power, opportunity, and technology. But under its gilded (plated in gold) surface, the second half of the nineteenth century contained a rotten core. In politics, business, labor, technology, agriculture, our continued conflict with Native Americans, immigration, and urbanization, the “Gilded Age” brought out the best and worst of the American experiment. While our nation’s population continued to grow, its civic health did not keep pace. The Civil War and Reconstruction led to waste, extravagance, speculation, and graft. The power of politicians and their political parties grew in direct proportion to their corruption. The Emergence of Political Machines- As cities experienced rapid urbanization, they were hampered by inefficient government. Political parties organized a new power structure to coordinate activities in cities. *** British historian James Bryce described late nineteenth-century municipal government as “the one conspicuous failure of the United States.” Political machines were the organized structure that controlled the activities of a political party in a city. o City Boss: . Controlled the political party throughout the city . Controlled access to city jobs and business licenses Example: Roscoe Conkling, New York City o Built parks, sewer systems, and water works o Provided money for schools hospitals, and orphanages o Ward Boss: . Worked to secure the vote in all precincts in a district . Helped gain the vote of the poor by provided services and doing favors Focused help for immigrants to o Gain citizenship o Find housing o Get jobs o Local Precinct Workers: . -

Native American Land Cessions, 1867-1890: an Annotated Bibliography of Selected Sources David Evensen St

St. Cloud State University theRepository at St. Cloud State Curriculum Unit on the Gilded Age in the United American History Lesson Plans States 1-8-2016 Native American Land Cessions, 1867-1890: An Annotated Bibliography of Selected Sources David Evensen St. Cloud State University Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.stcloudstate.edu/gilded_age Part of the Curriculum and Instruction Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Evensen, David, "Native American Land Cessions, 1867-1890: An Annotated Bibliography of Selected Sources" (2016). Curriculum Unit on the Gilded Age in the United States. 4. https://repository.stcloudstate.edu/gilded_age/4 This lesson is brought to you for free and open access by the American History Lesson Plans at theRepository at St. Cloud State. It has been accepted for inclusion in Curriculum Unit on the Gilded Age in the United States by an authorized administrator of theRepository at St. Cloud State. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Annotated Bibliography of Selected Sources in the Gilded Age, 1877-1900 by Dave Evensen Primary Sources: Bureau of Indian Affairs, Records of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, RG 75: McLaughlin’s Report, December 15, 1890, accessed November 11, 2015, http://www.archives.gov/global-pages/larger- image.html?i=/publications/prologue/2008/fall/images/gall-report- l.jpg&c=/publications/prologue/2008/fall/images/gall-report.caption.html This source is the report Indian Agent McLaughlin completed describing the casualties of Native Americans in a confrontation on December 15, 1890. This document includes a list of police force causalities. The names are listed using an English name and Native American name. -

Quick Prep Major Eras of American History

Quick Prep This Quick Prep section provides a handy reference to key facts on a variety of topics in American history. Major Eras of American History Era and Dates Description Pre-European Contact Flourishing societies of indigenous peoples live by hunting, farming, fishing, and trading. c. 1000 B.C.–1492 Exploration & Colonization Europeans explore, establish colonies, create conflict with Native Americans; European 1492–1763 rivalries continue. Revolutionary Era Maturing colonial economies; increasing tension with Great Britain leads to war and independence. 1763–1789 Early Republic New federal government; first political parties; uncertain international relations; 1789–1812 expansion to the Mississippi Westward Expansion Growth in transportation and industry; Jacksonian democracy; Manifest Destiny; 1812–1846 removal of Native Americans Antebellum Era Differences over expansion of slavery leads to increasing sectionalism; conflict with Mexico. 1836–1860 Civil War and War over states’ rights to secede and emancipation; union preserved; Reconstruction voting rights for African Americans 1860–1877 Industrial Age/ Immigration, industrialization, urbanization Big business, railroads, organized labor, Gilded Age machine politics 1877–1900 Progressive Era Reform—urban problems; temperance; government and business corruption; women’s right to vote. 1890–1920 American Imperialism America becomes a world power, gains overseas colonies. 1890–1920 World War I European conflict challenges U.S. policy of neutrality; Allied victory intended to make the world safe 1914–1918 for democracy. Roaring Twenties Business booms, superficial prosperity; new lifestyles for women; growth of mass media; Red Scare 1920–1929 Great Depression World trade declines, banks fail, high unemployment, urban and rural poverty; New Deal expands 1929–1941 role of federal government. -

The Gilded Age to the Great War: America at the Turn of the Century Timeline

The Gilded Age to the Great War: America at the Turn of the Century Timeline 1868 Congress enacted an eight-hour workday for federal workers. 1869 Union Pacific and Central Pacific completed the first transcontinental railway link. 1869 The women’s movement splits into two hostile groups: the National Woman Suffrage Association, led by Elizabeth Cady Stanton; and the American Woman Suffrage Association, led by Lucy Stone. 1869 The first collegiate game of football was played between Rutgers University and Princeton University. Rutgers won, 6 to 4. 1869 Knights of Labor, the first national union, was formed. 1869 Wyoming Territory granted women the right to vote. 1870 The Fifteenth Amendment guaranteed African Americans the right to vote. 1870 John D. Rockefeller founded the Standard Oil Company, which emerged as the country’s first industry-dominating trust. 1870 Hiram Revels of Mississippi became the first African American to serve in the U.S. Senate and Joseph Rainey of South Carolina became the first African American to serve in the U.S. House of Representatives. 1870 The Utah Territory was created, and granted women the right to vote. 1871 Congress passed the Ku Klux Klan Act, which made state officials liable in federal court for depriving anyone of their civil rights or the equal protection of the laws, and made the KKK’s intimidation tactics federal crimes. 1871 William “Boss” Tweed’s corrupt practices were exposed in a series of New York Times articles. 1871 In opposition to Asian immigration to the U.S., race riots erupted in Los Angeles and fifteen Chinese workers were lynched. -

Mass Culture As an Effect of World War I

Bella Jacoby Humanities 2014-15 Mrs. Tilley and Mr. Donnelly May 2015 Mass Culture as an Effect of World War I The 1920s are seen as a monumental decade in the cultural and social growth of the United States. The time was characterized by a devout commitment to celebration and enjoyment. This had been seen in eras before, especially after periods of economic growth and thriving. These post-success booms were typically characterized by an explosion of inventions, the dominance of Capitalism and the rise of corporations, and a growth in art and pop culture. Eras like these generally stimulate the growth of infrastructure and launch a nation forward into its next stage of progress. However, the 1920’s was different. It included all of these things, but alongside the celebration and progress was a distinct mass culture that emerged during the decade as a response to the psychological questions posed by World War I. Although this is often overlooked and hidden by the prosperity and frivolity of the decade, the war had a profound impact on the American psyche that would transform society. The evidence for the origins of this shift has been preserved through the new movement of Modernism in artwork and literature of the time, proving that the mass culture of America can be traced back to a crisis of purpose after World War I. This new culture, composed of art and music but also the boom of consumerism and materialism, would shape the next century of American life. The culture of the 1920s was characterized by a release of morals, an appreciation for wealth, and a growing feeling of connection within the nation. -

The Gilded Age & the Progressive Movement

The Gilded Age & The Progressive Movement Gilded Age Progressive Movement A movement by reformers to improve Time in the late 1800s and early 1900s society. These reforms included change in when the US and its cities seemed nice on government, business and society. the outside, but had lots of problems on the inside. BRAINSTORM: WHAT PROBLEMS EXISTED IN CITIES AND IN THE UNITED STATES DURING THE GILDED AGE? Political corruption Monopolies Little education for many Poor working conditions Child labor Crime Pollution / Abuse of natural resources Few rights for minorities Poor living conditions Muckrakers Define muckraker: Journalists who wrote newspaper and magazine stories that brought problems to the attention of the public. Examples: Jacob Riis: Photographed and wrote about the poor and living conditions in the cities in his book How the Other Half Lives Upton Sinclair: Wrote The Jungle, which described the horrors of the meatpacking industry. Ida Tarbell: Wrote about the unfair practices of the Standard Oil Company. Led to public pressure for the government to get involved. 1 Reformers Define reformer: A person that wants to bring change to improve society. Define progressive: The same thing as a reformer. During this time period, progressives wanted to fix the problems that they saw in society, many of which they believed were caused by rapid industrialization. Examples: Jane Addams: founded Hull House to help poor immigrants. This became a model for other settlement houses. Susan B. Anthony & Elizabeth Cady Stanton: formed the National Woman Suffrage Association to try to get the vote for women. Other suffragists included Alice Paul and Carrie Chapman Catt. -

Immigration in the Gilded Age and Progressive Era

HANDOUT B Immigration in the Gilded Age and Progressive Era Directions: Read the essay and answer the questions that follow. It is impossible to understand the American Coming to America experience without understanding the impact of Migration is the movement of a person from one immigration. The millions of immigrants who geographic location to another. The immigrants came to the United States settled across the of the late nineteenth century came primarily nation, named its cities, helped build its canals, from southeastern and northwestern Europe, roads, and railroads, mined its ore, and shaped Asia, and from Mexico and Canada in North its culture. To understand immigration in the America. The migrants only became immigrants United States is to understand the history of the when they crossed the international border for country itself. the United States. It is this factor that makes Between 1880 and 1920, over twenty million immigration a matter of law between countries. people immigrated to the United States. Men, For immigrants of this era, and any era, women, and children from across the world, the long journey to a new home began with seeking the opportunity and freedom available a decision. Uprooting themselves from their in a society rooted in the principles of the homes, farms, and jobs was an arduous process. Declaration of Independence. They traveled The immigrants came to the United States thousands of miles in the hope of providing a for different reasons. For many immigrants better life for themselves and their families in in the late nineteenth century, there was the economic opportunities available in a free- something that pushed them out, such as slow enterprise, industrial economy. -

Table of Contents 1. Structural Factors Affecting Differences in Infant

Table of contents 1. Structural factors affecting differences in infant mortality for whites and non-whites in the United States in 1960 2. Black separatism in contemporary America: Evolution of an ideology 3. Rediscovering America's sacred ground: Reframing the debate about the role of religion in shaping American values 4. The impact of growth and changes in computer use at work in the United States: An analysis of wages by occupation, industry, and gender, 1984--2001 5. Out of many...: A social history of the homosexual rights movement as originated and continued in Los Angeles, California 6. Food deserts: A feminist study of Washington, D.C. 7. "Burlesque Female Behemoths": Transgressions of Fat, Femme Burlesque 8. The Social Citizenship Tradition in Anglo-American Thought 9. Rivers of Power: Indians and Colonists in the North American Midcontinent 10. Contentious Cosmopolitans: Black Public History and Civil Rights in Cold War Chicago, 1942-1972 11. Building bridges across cultures: A case study of the people-to-people campaign, 1956-1975 12. Rhetoric, world-view, and strategy in united states national security strategy documents 13. The Ritual Significance of the National Pastime over the Long Duration: Democracy, Racial Progress, and African Americans in Baseball 14. Navigating identity through philanthropy: A history of the Islamic Society of North America (1979--2008) 15. Geography on Foot and at Hand: Senses of Place in American Nature Writing 16. America's Search for Control in Iraq in the Early Cold War, 1953-1961 17. This is What A Feminist Looks Like: The New Woman Image, American Feminism, and the Politics of Women's Fashion 1890-1930 18.