The Uses of Federalism: the American Experience

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Devolution/New Federalism About Devolution

Devolution/New Federalism About Devolution Devolution, also known as New Federalism, is the transfer of certain powers from the United States federal government back to the states. It started under Ronald Reagan over concerns that the federal government had too much power (as is seen during Franklin D. Roosevelt’s “New Deal” program and Lyndon B. Johnson’s “Great Society” program). Reagan Revolution (1981-1989) ● “New Federalism” evolved after the election of Republican President Ronald Reagan, in which he promised to return power to the states in an effort to even out the balance of strength between the national and state governments. ● Replaced the general revenue sharing with block grants as the primary funding for states. ● Introduced his Economic Policy Goals: Reaganomics, which focused on federal spending, taxation, regulation, and inflation. ● These economic reliefs gave more power to the states by lessening their reliance on the federal government. Bill Clinton’s Presidency (1993-2001) ● Bill Clinton was the first Democratic president in 12 years. Despite this, Clinton largely campaigned against a strong federal government due to the large Republican house majority during his presidency and Newt Gingrich’s priority of “New Federalism.” ● Passed the Unfunded Mandates Act of 1995 gave states a larger say in federal spendings. ● Passed the Personal Responsibility and Work Economic Opportunity Reconciliation Act of 1996 (later replaced by the TANF), which gave state governments control over welfare. Policies Block Grants - Prominent type of grant given to states by the federal government during and after the Reagan Administration. The federal government gives money to the state governments with only general provisions on how it is to be spent (“flexible funding”). -

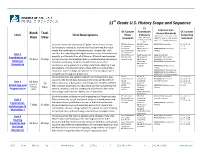

11 Grade U.S. History Scope and Sequence

th 11 Grade U.S. History Scope and Sequence C3 Common Core DC Content Framework DC Content Block Trad. Literacy Standards Unit Unit Descriptions Power Indicators RH.11-12.1, 11-12.2, 11-12.10 Supporting Days Days Standards D3.1, D4.3 and WHST.11-12.4, 11-12.5, 11-12.9 Standards D4.6 apply to each and 11-12.10 apply to each unit. unit. Students review the content of 8th grade United States History 11.1.6: Influences D1.4: Emerging RH.11-12.4: Vocabulary 11.1.1-11.1.5 on American questions 11.1.8 (colonization, revolution, and civil war) by examining the major Revolution D4.2: Construct WHST.11-12.2: Explanatory 11.1.10 trends from colonialism to Reconstruction. In particular, they 11.1.7: Formation explanations Writing of Constitution Unit 1 consider the expanding role of government, issues of freedom and 11.1.9: Effects of Apply to each unit: Apply to each unit: Foundations of equality, and the definition of citizenship. Students read complex Civil War and D3.1: Sources RH.11-12.1: Cite evidence 10 days 20 days primary sources, summarizing based on evidence while developing Reconstruction D4.3: Present RH.11-12.2: Central idea American historical vocabulary. Students should communicate their information RH.11-12.10: Comprehension D4.6: Analyze Democracy conclusions using explanatory writing, potentially adapting these problems WHST.11-12.4: Appropriate explanations into other formats to share within or outside their writing classroom. Students begin to examine the relationship between WHST.11-12.5: Writing process WHST.11-12.9: Using evidence compelling and supporting questions. -

American History 1 SSTH 033 061 Credits: 0.5 Units / 5 Hours / NCAA

UNIVERSITY OF NEBRASKA HIGH SCHOOL American History 1 SSTH 033 061 Credits: 0.5 units / 5 hours / NCAA Course Description This course discusses the development of America from the colonial era until the start of the twentieth century. This includes European exploration and the collision between different societies (including European, African, and Native American). The course also explores the formation of the American government and how democracy in the United States affected thought and culture. Students will also learn about the influences of the Enlightenment on different cultural groups, religion, political and philosophical writings. Finally, they will examine various reform efforts, the Civil War, and the effects of expansion, immigration, and urbanization on American society. Graded Assessments: 5 Unit Evaluations; 3 Projects; 3 Proctored Progress Tests; 5 Teacher Connect Activities Course Objectives When you have completed the materials in this course, you should be able to: 1. Identify the Native American societies that existed before 1492. 2. Explain the reasons for European exploration and colonization. 3. Describe the civilizations that existed in Africa during the Age of Exploration. 4. Explore how Europeans, Native Americans, and Africans interacted in colonial America. 5. Summarize the ideas of the Enlightenment and the Great Awakening. 6. Examine the reasons for the American Revolution. 7. Discuss how John Locke’s philosophy influenced the Declaration of Independence. 8. Understand how the American political system works. 9. Trace the development of American democracy from the colonial era through the Gilded Age. 10. Evaluate the development of agriculture in America from the colonial era through the Gilded Age. -

State Constitutional Law, New Judicial Federalism, and the Rehnquist Court

Cleveland State Law Review Volume 51 Issue 3 Symposium: The Ohio Constitution - Article 4 Then and Now 2004 State Constitutional Law, New Judicial Federalism, and the Rehnquist Court Shirley S. Abrahamson Chief Justice, Wisconsin Supreme Court Follow this and additional works at: https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/clevstlrev Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, and the State and Local Government Law Commons How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! Recommended Citation Shirley S. Abrahamson, State Constitutional Law, New Judicial Federalism, and the Rehnquist Court , 51 Clev. St. L. Rev. 339 (2004) available at https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/clevstlrev/vol51/iss3/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at EngagedScholarship@CSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Cleveland State Law Review by an authorized editor of EngagedScholarship@CSU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STATE CONSTITUTIONAL LAW, NEW JUDICIAL FEDERALISM, AND THE REHNQUIST COURT SHIRLEY S. ABRAHAMSON1 Dean Steinglass, faculty, students, fellow panelists, guests. Ohio, as you all know, was admitted to the Union on March 1, 1803.2 It was the seventeenth state.3 The state is celebrating this 200th anniversary with a yearlong series of activities honoring the state’s rich history: bicentennial bells, historical markers, celebration of Ohio’s role in the birth and development of aviation and aerospace, Ohio’s Tall Ship Challenge, Tall Stacks on the Ohio River, and a bicentennial stamp. The Ohio legal system also celebrates the bicentennial. It celebrates in quiet contemplation of its state constitutional history. -

Domestic Relations, Missouri V. Holland, and the New Federalism

William & Mary Bill of Rights Journal Volume 12 (2003-2004) Issue 1 Article 5 December 2003 Domestic Relations, Missouri v. Holland, and the New Federalism Mark Strasser Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmborj Part of the Family Law Commons Repository Citation Mark Strasser, Domestic Relations, Missouri v. Holland, and the New Federalism, 12 Wm. & Mary Bill Rts. J. 179 (2003), https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmborj/vol12/iss1/5 Copyright c 2003 by the authors. This article is brought to you by the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmborj DOMESTIC RELATIONS, MISSOURI v. HOLLAND, AND THE NEW FEDERALISM Mark Strasser* INTRODUCTION Over the past several years, the United States Supreme Court has been limiting Congress's power under the Commerce Clause and under Section 5 of the Fourteenth Amendment.' During this same period, the Court has emphasized the importance of state sovereignty and has expanded the constitutional protections afforded the states under the Tenth and Eleventh Amendments. 2 These developments notwithstanding, commentators seem confident that the treaty power is and will remain virtually plenary, even if the federal government might make use of it to severely undermine the dignity and sovereignty of the states.3 That confidence is misplaced. While it is difficult to predict what the Court would do were an appropriate opportunity to present itself, the doctrinal explanations that would be necessary to support a much less robust treaty power would be much easier to make than most commentators seem to realize, even if one brackets recent developments in constitutional law. -

The New Federalism After United States Vs. Lopez - Introduction

Case Western Reserve Law Review Volume 46 Issue 3 Article 4 1996 The New Federalism after United States vs. Lopez - Introduction Jonathan L. Entin Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/caselrev Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Jonathan L. Entin, The New Federalism after United States vs. Lopez - Introduction, 46 Case W. Rsrv. L. Rev. 635 (1996) Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/caselrev/vol46/iss3/4 This Symposium is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Journals at Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Case Western Reserve Law Review by an authorized administrator of Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. INTRODUCTION JonathanL. Entin* Arguments about the proper role of the federal government have been a staple of American political life. That topic was at the core of the debate over ratification of the Constitution, and it re- mains a central issue in contemporary politics.' Although the argu- ments typically have a strong pragmatic aspect (e.g., whether pub- lic policy is made more effectively at the state or local level than at the national level), much of the debate explicitly invokes con- stitutional values. This is neither surprising nor inappropriate, be- cause the Constitution is more than "what the judges say it is." It also provides the framework for our government and our politics. In light of our "profound national commitment to the principle that debate on public issues should be uninhibited, robust, and wide- open,"3 we should expect our fundamental charter to figure in public discourse. -

U.S. History Objectives

U.S. History Objectives Unit 1 An Age of Prosperity and Corruption Students will understand the internal growth of the United States during the period of 1850s-1900. • Identify the conditions that led to Industrial expansion. • Compare and contrast politics of the Gilded Age and today’s governmental systems. • Describe how immigration was changing the social landscape of the United States resulting in the need for reform. Analyze and interpret maps, tables, and charts. Identify key terms. The Expansion of American Industry 1850-1920 Students will understand the conditions that led to Industrial expansion. • Identify the conditions that led to Industrial expansion. • Describe the technological revolution and the impact of the railroads and inventions. • Explain the growth of labor unions and the methods used by workers to achieve reform. Politics, 1870-1915 Students will understand the changes in cities and politics during the period known as the Gilded Age. • Compare and contrast politics of the Gilded Age and today’s governmental systems. • Be able to communicate why American cities experienced rapid growth. • Summarize the growth of Big Business and the role of monopolies. Immigration and Urban Life, 1870-1915 Students will understand the impact of immigration on the social landscape of the United States. • Analyze and interpret maps, tables, and charts. • Identify key terms. Give examples of how immigration was changing the social landscape of the United States. Relate the reasons for reform and the impact of the social movement. Unit 2 Internal and External Role of the United States Students will describe the changing internal and external roles of the United States between 1890- 1920. -

Indigenous and Settler Violence During the Gilded Age and Progressive Era John R

Indigenous and Settler Violence during the Gilded Age and Progressive Era John R. Legg, George Mason University The absence of Indigenous historical perspectives creates a lacuna in the historiography of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era. For the first eight years of the Journal of the Gilded Age and the Progressive Era, zero articles written about or by Native Americans can be found within its pages. By 2010, however, a roundtable of leading Gilded Age and Progressive Era scholars critically examined the reasons why “Native Americans often slipped out of national consciousness by the Gilded Age and Progressive Era.”1 By 2015, the Journal offered a special issue on the importance of Indigenous histories during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, a “period of tremendous violence perpetuated on Indigenous communities,” wrote the editors Boyd Cothran and C. Joseph Genetin-Pilawa.2 It is the observation of Indigenous histories on the periphery of Gilded Age and Progressive Era that inspires a reevaluation of the historiographical contributions that highlight Indigenous survival through the onslaught of settler colonial violence during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The purpose of this microsyllabus seeks to challenge these past historiographical omissions by re-centering works that delve into the inclusion of Indigenous perspectives and experience of settler colonial violence during the Gilded Age and Progressive Era. Ultimately, this microsyllabus helps us unravel two streams of historiographical themes: physical violence and structural violence. Violence does not always have to be physical, but can manifest in different forms: oppression, limiting people’s rights, their access to legal representation, their dehumanization through exclusion and segregation, as well as the production of memory. -

The Politics of the Gilded Age

Unit 3 Class Notes- The Gilded Age The Politics of the Gilded Age The term “Gilded Age” was coined by Mark Twain in 1873 to describe the era in America following the Civil War; an era that from the outside looked to be a fantastic growth of wealth, power, opportunity, and technology. But under its gilded (plated in gold) surface, the second half of the nineteenth century contained a rotten core. In politics, business, labor, technology, agriculture, our continued conflict with Native Americans, immigration, and urbanization, the “Gilded Age” brought out the best and worst of the American experiment. While our nation’s population continued to grow, its civic health did not keep pace. The Civil War and Reconstruction led to waste, extravagance, speculation, and graft. The power of politicians and their political parties grew in direct proportion to their corruption. The Emergence of Political Machines- As cities experienced rapid urbanization, they were hampered by inefficient government. Political parties organized a new power structure to coordinate activities in cities. *** British historian James Bryce described late nineteenth-century municipal government as “the one conspicuous failure of the United States.” Political machines were the organized structure that controlled the activities of a political party in a city. o City Boss: . Controlled the political party throughout the city . Controlled access to city jobs and business licenses Example: Roscoe Conkling, New York City o Built parks, sewer systems, and water works o Provided money for schools hospitals, and orphanages o Ward Boss: . Worked to secure the vote in all precincts in a district . Helped gain the vote of the poor by provided services and doing favors Focused help for immigrants to o Gain citizenship o Find housing o Get jobs o Local Precinct Workers: . -

Block Grants: Perspectives and Controversies

Block Grants: Perspectives and Controversies Updated February 21, 2020 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R40486 Block Grants: Perspectives and Controversies Summary Block grants provide state and local governments funding to assist them in addressing broad purposes, such as community development, social services, public health, or law enforcement, and generally provide them more control over the use of the funds than categorical grants. Block grant advocates argue that block grants increase government efficiency and program effectiveness by redistributing power and accountability through decentralization and partial devolution of decisionmaking authority from the federal government to state and local governments. Advocates also view them as a means to reduce the federal deficit. For example, the Trump Administration’s FY2020 budget request recommended that Medicaid be set “on a sound fiscal path ... by putting States on equal footing with the Federal Government to implement comprehensive Medicaid financing reform through a per capita cap or block grant.... [the proposal would] empower States to design State-based solutions that prioritize Medicaid dollars for the most vulnerable and support innovation.” The Trump Administration’s FY2021 budget request added that “Medicaid reform would restore balance, flexibility, integrity, and accountability to the State-Federal partnership.” Block grant critics argue that block grants can undermine the achievement of national objectives and can be used as a “backdoor” means to reduce government spending on domestic issues. For example, opponents of converting Medicaid into a block grant argue that “block granting Medicaid is simply code for deep, arbitrary cuts in support to the most vulnerable seniors, individuals with disabilities, and low-income children.” Block grant critics also argue that block grants’ decentralized nature makes it difficult to measure their performance and to hold state and local government officials accountable for their decisions. -

Gonzales V. Raich: Has New Federalism Gone up in Smoke?

CASENOTE Gonzales v. Raich: Has New Federalism Gone up in Smoke? In Gonzales v. Raich,1 the United States Supreme Court broke with recent federalist trends2 by holding that Congress did not exceed its Commerce Clause' power in prohibiting the local growth and use of marijuana, which was legal under California state law.4 While the Court asserted that this case did not break with recent precedent restricting Congress's Commerce Clause power,5 this decision reaffirms 1. 125 S. Ct. 2195 (2005). 2. The Court, in recent years, has struck two laws on federalist principles. United States v. Lopez, 514 U.S. 549 (1995); Morrison v. United States, 529 U.S. 598 (2000). 3. The Commerce Clause of the United States Constitution provides that Congress has the power "[t]o regulate Commerce... among the several States....." U.S. CONST. art 1, § 8, cl. 3. 4. California's Compassionate Use Act of 1996 provides that its purpose is: To ensure that seriously ill Californians have the right to obtain and use marijuana for medical purposes where that medical use is deemed appropriate and has been recommended by a physician who has determined that the person's health would benefit from the use of marijuana in the treatment of cancer, anorexia, AIDS, chronic pain, spasticity, glaucoma, arthritis, migraine, or any other illness for which marijuana provides relief. CAL. HEALTH & SAFE. CODE ANN. § 11362.5(b)(1)(A) (West Supp. 2005). 5. Gonzales, 125 S. Ct. at 2209-11. 1309 1310 MERCER LAW REVIEW [Vol. 57 expansive congressional power and creates uncertainty about whether federalist principles limit congressional power. -

The Commerce Clause and Federalism After Lopez and Morrison: the Case for Closing the Jurisdictional-Element Loophole

The Commerce Clause and Federalism after Lopez and Morrison: The Case for Closing the Jurisdictional-Element Loophole Diane McGimseyt TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ............................................................................................ 1677 I. Federalism: The Principle at Stake in Lopez and Morrison ........... 1682 II. How a State-Line Crossing Became Sufficient to Invoke the Commerce Clause Power ................................................................ 1685 A. Substantial-Effects Prong ......................................................... 1689 B. Regulation of the Channels and Instrumentalities of Interstate C omm erce ................................................................................. 1691 1. Instrumentalities of Interstate Commerce .......................... 1692 2. Channels of Interstate Commerce ...................................... 1696 3. The Jurisdictional Element ................................................. 1699 III. Lopez and Morrison: How the Apparent "Revolution" in Congress's Commerce Clause Power Left that Power Essentially Intact .......... 1701 IV. The Jurisdictional Element and Federalism: Why the Commerce Clause Still Needs Revisiting .......................................................... 1706 A. Implications of the Growth of the U.S. Economy .................... 1706 B. Lower Court Decisions ............................................................. 1710 1. Federal Carjacking Statute ................................................. 1710 2. Felon-in-Possession