Culture, Communication, and Changing Representations of Lolita in Japan and the West

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vladimir Nabokov Lolita by John Lennard “There Are No Verbal Obscenities

Literature Insights General Editor: Charles Moseley Vladimir Nabokov Lolita by John Lennard “there are no verbal obscenities ... in Lolita, only the low moans of ... abused pain.” HEB ☼ FOR ADVICE ON THE USE OF THIS EBOOK PLEASE SCROLL TO PAGE 2 Reading t * This book is designed to be read in single page view, using the ‘fit page’ command. * To navigate through the contents use the hyperlinked ‘Book- marks’ at the left of the screen. * To search, click the magnifying glass symbol and select ‘show all results’. * For ease of reading, use <CTRL+L> to enlarge the page to full screen, and return to normal view using < Esc >. * Hyperlinks (if any) appear in Blue Underlined Text. Permissions Your purchase of this ebook licenses you to read this work on- screen. No part of this publication may be otherwise reproduced or transmitted or distributed without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher. You may print one copy of the book for your own use but copy and paste functions are disabled. Making or distributing copies of this book would constitute copyright infringement and would be liable to prosecution. Thank you for respecting the rights of the author. ISBN 978-1-84760-073-8 Vladimir Nabokov: ‘Lolita’ John Lennard HEB ☼ Humanities-Ebooks, LLP Copyright © John Lennard, 2008 The Author has asserted his right to be identified as the author of this Work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. First published by Humanities-Ebooks, LLP, Tirril Hall, Tirril, Penrith CA10 2JE Contents Preface Part 1. -

Constructing and Consuming an Ideal in Japanese Popular Culture

Running head: KAWAII BOYS AND IKEMEN GIRLS 1 Kawaii Boys and Ikemen Girls: Constructing and Consuming an Ideal in Japanese Popular Culture Grace Pilgrim University of Florida KAWAII BOYS AND IKEMEN GIRLS 2 Table of Contents Abstract………………………………………………………………………………………..3 Introduction……………………………………………………………………………………4 The Construction of Gender…………………………………………………………………...6 Explication of the Concept of Gender…………………………………………………6 Gender in Japan………………………………………………………………………..8 Feminist Movements………………………………………………………………….12 Creating Pop Culture Icons…………………………………………………………………...22 AKB48………………………………………………………………………………..24 K-pop………………………………………………………………………………….30 Johnny & Associates………………………………………………………………….39 Takarazuka Revue…………………………………………………………………….42 Kabuki………………………………………………………………………………...47 Creating the Ideal in Johnny’s and Takarazuka……………………………………………….52 How the Companies and Idols Market Themselves…………………………………...53 How Fans Both Consume and Contribute to This Model……………………………..65 The Ideal and What He Means for Gender Expression………………………………………..70 Conclusion……………………………………………………………………………………..77 References……………………………………………………………………………………..79 KAWAII BOYS AND IKEMEN GIRLS 3 Abstract This study explores the construction of a uniquely gendered Ideal by idols from Johnny & Associates and actors from the Takarazuka Revue, as well as how fans both consume and contribute to this model. Previous studies have often focused on the gender play by and fan activities of either Johnny & Associates talents or Takarazuka Revue actors, but never has any research -

Athletic Inspiration: Vladimir Nabokov and the Aesthetic Thrill of Sports Tim Harte Bryn Mawr College, [email protected]

Bryn Mawr College Scholarship, Research, and Creative Work at Bryn Mawr College Russian Faculty Research and Scholarship Russian 2009 Athletic Inspiration: Vladimir Nabokov and the Aesthetic Thrill of Sports Tim Harte Bryn Mawr College, [email protected] Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy . Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.brynmawr.edu/russian_pubs Custom Citation Harte, Tim. "Athletic Inspiration: Vladimir Nabokov and the Aesthetic Thrill of Sports," Nabokov Studies 12.1 (2009): 147-166. This paper is posted at Scholarship, Research, and Creative Work at Bryn Mawr College. http://repository.brynmawr.edu/russian_pubs/1 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Tim Harte Bryn Mawr College Dec. 2012 Athletic Inspiration: Vladimir Nabokov and the Aesthetic Thrill of Sports “People have played for as long as they have existed,” Vladimir Nabokov remarked in 1925. “During certain eras—holidays for humanity—people have taken a particular fancy to games. As it was in ancient Greece and ancient Rome, so it is in our present-day Europe” (“Braitenshtreter – Paolino,” 749). 1 For Nabokov, foremost among these popular games were sports competitions. An ardent athlete and avid sports fan, Nabokov delighted in the competitive spirit of athletics and creatively explored their aesthetic as well as philosophical ramifications through his poetry and prose. As an essential, yet underappreciated component of the Russian-American writer’s art, sports appeared first in early verse by Nabokov before subsequently providing a recurring theme in his fiction. The literary and the athletic, although seemingly incongruous modes of human activity, frequently intersected for Nabokov, who celebrated the thrills, vigor, and beauty of sports in his present-day “holiday for humanity” with a joyous energy befitting such physical activity. -

Clothing Fantasies: a Case Study Analysis Into the Recontextualization and Translation of Subcultural Style

Clothing fantasies: A case study analysis into the recontextualization and translation of subcultural style by Devan Prithipaul B.A., Concordia University, 2019 Extended Essay Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the School of Communication (Dual Degree Program in Global Communication) Faculty of Art, Communication and Technology © Devan Prithipaul 2020 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Summer 2020 Copyright in this work rests with the author. Please ensure that any reproduction or re-use is done in accordance with the relevant national copyright legislation. Approval Name: Devan Prithipaul Degree: Master of Arts Title: Clothing fantasies: A case study analysis into the recontextualization and translation of subcultural style Program Director: Katherine Reilly Sun-Ha Hong Senior Supervisor Assistant Professor ____________________ Katherine Reilly Program Director Associate Professor ____________________ Date Approved: August 31, 2020 ii Abstract Although the study of subcultures within a Cultural Studies framework is not necessarily new, what this research studies is the process of translation and recontextualization that occurs within the transnational migration of a subculture. This research takes the instance of punk subculture in Japan as a case study for examining how this subculture was translated from its original context in the U.K. The frameworks which are used to analyze this case study are a hybrid of Gramscian hegemony and Lacanian psychoanalysis. The theoretical applications for this research are the study of subcultural migration and the processes of translation and recontextualization. Keywords: subculture; Cultural Studies; psychoanalysis; hegemony; fashion communication; popular communication iii Dedication Glory to God alone. iv Acknowledgements “Ideas come from pre-existing ideas” was the first phrase I heard in a university classroom, and this statement is ever more resonant when acknowledging those individuals who have led me to this stage in my academic journey. -

Notes for Chapter Re-Drafts

Making Markets for Japanese Cinema: A Study of Distribution Practices for Japanese Films on DVD in the UK from 2008 to 2010 Jonathan Wroot PhD Thesis Submitted to the University of East Anglia For the qualification of PhD in Film Studies 2013 1 Making Markets for Japanese Cinema: A Study of Distribution Practices for Japanese Films on DVD in the UK from 2008 to 2010 2 Acknowledgements Thanks needed to be expressed to a number of people over the last three years – and I apologise if I forget anyone here. First of all, thank you to Rayna Denison and Keith Johnston for agreeing to oversee this research – which required reining in my enthusiasm as much as attempting to tease it out of me and turn it into coherent writing. Thanks to Mark Jancovich, who helped me get started with the PhD at UEA. A big thank you also to Andrew Kirkham and Adam Torel for doing what they do at 4Digital Asia, Third Window, and their other ventures – if they did not do it, this thesis would not exist. Also, a big thank you to my numerous other friends and family – whose support was invaluable, despite the distance between most of them and Norwich. And finally, the biggest thank you of all goes to Christina, for constantly being there with her support and encouragement. 3 Abstract The thesis will examine how DVD distribution can affect Japanese film dissemination in the UK. The media discourse concerning 4Digital Asia and Third Window proposes that this is the principal factor influencing their films’ presence in the UK from 2008 to 2010. -

Imōto-Moe: Sexualized Relationships Between Brothers and Sisters in Japanese Animation

Imōto-Moe: Sexualized Relationships Between Brothers and Sisters in Japanese Animation Tuomas Sibakov Master’s Thesis East Asian Studies Faculty of Humanities University of Helsinki November 2020 Tiedekunta – Fakultet – Faculty Koulutusohjelma – Utbildningsprogram – Degree Programme Faculty of Humanities East Asian Studies Opintosuunta – Studieinriktning – Study Track East Asian Studies Tekijä – Författare – Author Tuomas Valtteri Sibakov Työn nimi – Arbetets titel – Title Imōto-Moe: Sexualized Relationships Between Brothers and Sisters in Japanese Animation Työn laji – Arbetets art – Level Aika – Datum – Month and Sivumäärä– Sidoantal – Number of pages Master’s Thesis year 83 November 2020 Tiivistelmä – Referat – Abstract In this work I examine how imōto-moe, a recent trend in Japanese animation and manga in which incestual connotations and relationships between brothers and sisters is shown, contributes to the sexualization of girls in the Japanese society. This is done by analysing four different series from 2010s, in which incest is a major theme. The analysis is done using visual analysis. The study concludes that although the series can show sexualization of drawn underage girls, reading the works as if they would posit either real or fictional little sisters as sexual targets. Instead, the analysis suggests that following the narrative, the works should be read as fictional underage girls expressing a pure feelings and sexuality, unspoiled by adult corruption. To understand moe, it is necessary to understand the history of Japanese animation. Much of the genres, themes and styles in manga and anime are due to Tezuka Osamu, the “god of manga” and “god of animation”. From the 1950s, Tezuka was influenced by Disney and other western animators at the time. -

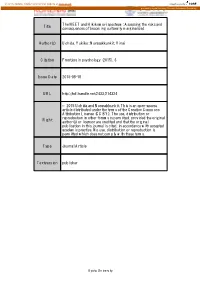

Title the NEET and Hikikomori Spectrum

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Kyoto University Research Information Repository The NEET and Hikikomori spectrum: Assessing the risks and Title consequences of becoming culturally marginalized. Author(s) Uchida, Yukiko; Norasakkunkit, Vinai Citation Frontiers in psychology (2015), 6 Issue Date 2015-08-18 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2433/214324 © 2015 Uchida and Norasakkunkit. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original Right author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms. Type Journal Article Textversion publisher Kyoto University ORIGINAL RESEARCH published: 18 August 2015 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01117 The NEET and Hikikomori spectrum: Assessing the risks and consequences of becoming culturally marginalized Yukiko Uchida 1* and Vinai Norasakkunkit 2 1 Kokoro Research Center, Kyoto University, Kyoto, Japan, 2 Department of Psychology, Gonzaga University, Spokane, WA, USA An increasing number of young people are becoming socially and economically marginalized in Japan under economic stagnation and pressures to be more globally competitive in a post-industrial economy. The phenomena of NEET/Hikikomori (occupational/social withdrawal) have attracted global attention in recent years. Though the behavioral symptoms of NEET and Hikikomori can be differentiated, some commonalities in psychological features can be found. Specifically, we believe that both NEET and Hikikomori show psychological tendencies that deviate from those Edited by: Tuukka Hannu Ilmari Toivonen, governed by mainstream cultural attitudes, values, and behaviors, with the difference University of London, UK between NEET and Hikikomori being largely a matter of degree. -

Willieverbefreelikeabird Ba Final Draft

Háskóli Íslands Hugvísindasvið Japanskt mál og menning Fashion Subcultures in Japan A multilayered history of street fashion in Japan Ritgerð til BA-prófs í japönsku máli og menningu Inga Guðlaug Valdimarsdóttir Kt: 0809883039 Leðbeinandi: Gunnella Þorkellsdóttir September 2015 1 Abstract This thesis discusses the history of the street fashion styles and its accompanying cultures that are to be found on the streets of Japan, focusing on the two most well- known places in Tokyo, namely Harajuku and Shibuya, as well as examining if the economic turmoil in Japan in the 1990s had any effect on the Japanese street fashion. The thesis also discusses youth cultures, not only those in Japan, but also in North- America, Europe, and elsewhere in the world; as well as discussing the theories that exist on the relation of fashion and economy of the Western world, namely in North- America and Europe. The purpose of this thesis is to discuss the possible causes of why and how the Japanese street fashion scene came to be into what it is known for today: colorful, demiurgic, and most of all, seemingly outlandish to the viewer; whilst using Japanese society and culture as a reference. Moreover, the history of certain street fashion styles of Tokyo is to be examined in this thesis. The first chapter examines and discusses youth and subcultures in the world, mentioning few examples of the various subcultures that existed, as well as introducing the Japanese school uniforms and the culture behind them. The second chapter addresses how both fashion and economy influence each other, and how the fashion in Japan was before its economic crisis in 1991. -

The Otaku Phenomenon : Pop Culture, Fandom, and Religiosity in Contemporary Japan

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 12-2017 The otaku phenomenon : pop culture, fandom, and religiosity in contemporary Japan. Kendra Nicole Sheehan University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Part of the Comparative Methodologies and Theories Commons, Japanese Studies Commons, and the Other Religion Commons Recommended Citation Sheehan, Kendra Nicole, "The otaku phenomenon : pop culture, fandom, and religiosity in contemporary Japan." (2017). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 2850. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/2850 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE OTAKU PHENOMENON: POP CULTURE, FANDOM, AND RELIGIOSITY IN CONTEMPORARY JAPAN By Kendra Nicole Sheehan B.A., University of Louisville, 2010 M.A., University of Louisville, 2012 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of the University of Louisville in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Humanities Department of Humanities University of Louisville Louisville, Kentucky December 2017 Copyright 2017 by Kendra Nicole Sheehan All rights reserved THE OTAKU PHENOMENON: POP CULTURE, FANDOM, AND RELIGIOSITY IN CONTEMPORARY JAPAN By Kendra Nicole Sheehan B.A., University of Louisville, 2010 M.A., University of Louisville, 2012 A Dissertation Approved on November 17, 2017 by the following Dissertation Committee: __________________________________ Dr. -

The Significance of Anime As a Novel Animation Form, Referencing Selected Works by Hayao Miyazaki, Satoshi Kon and Mamoru Oshii

The significance of anime as a novel animation form, referencing selected works by Hayao Miyazaki, Satoshi Kon and Mamoru Oshii Ywain Tomos submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Aberystwyth University Department of Theatre, Film and Television Studies, September 2013 DECLARATION This work has not previously been accepted in substance for any degree and is not being concurrently submitted in candidature for any degree. Signed………………………………………………………(candidate) Date …………………………………………………. STATEMENT 1 This dissertation is the result of my own independent work/investigation, except where otherwise stated. Other sources are acknowledged explicit references. A bibliography is appended. Signed………………………………………………………(candidate) Date …………………………………………………. STATEMENT 2 I hereby give consent for my dissertation, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter-library loan, and for the title and summary to be made available to outside organisations. Signed………………………………………………………(candidate) Date …………………………………………………. 2 Acknowledgements I would to take this opportunity to sincerely thank my supervisors, Elin Haf Gruffydd Jones and Dr Dafydd Sills-Jones for all their help and support during this research study. Thanks are also due to my colleagues in the Department of Theatre, Film and Television Studies, Aberystwyth University for their friendship during my time at Aberystwyth. I would also like to thank Prof Josephine Berndt and Dr Sheuo Gan, Kyoto Seiko University, Kyoto for their valuable insights during my visit in 2011. In addition, I would like to express my thanks to the Coleg Cenedlaethol for the scholarship and the opportunity to develop research skills in the Welsh language. Finally I would like to thank my wife Tomoko for her support, patience and tolerance over the last four years – diolch o’r galon Tomoko, ありがとう 智子. -

“Down the Rabbit Hole: an Exploration of Japanese Lolita Fashion”

“Down the Rabbit Hole: An Exploration of Japanese Lolita Fashion” Leia Atkinson A thesis presented to the Faculty of Graduate and Post-Doctoral Studies in the Program of Anthropology with the intention of obtaining a Master’s Degree School of Sociology and Anthropology Faculty of Social Sciences University of Ottawa © Leia Atkinson, Ottawa, Canada, 2015 Abstract An ethnographic work about Japanese women who wear Lolita fashion, based primarily upon anthropological field research that was conducted in Tokyo between May and August 2014. The main purpose of this study is to investigate how and why women wear Lolita fashion despite the contradictions surrounding it. An additional purpose is to provide a new perspective about Lolita fashion through using interview data. Fieldwork was conducted through participant observation, surveying, and multiple semi-structured interviews with eleven women over a three-month period. It was concluded that women wear Lolita fashion for a sense of freedom from the constraints that they encounter, such as expectations placed upon them as housewives, students or mothers. The thesis provides a historical chapter, a chapter about fantasy with ethnographic data, and a chapter about how Lolita fashion relates to other fashions as well as the Cool Japan campaign. ii Acknowledgements Throughout the carrying out of my thesis, I have received an immense amount of support, for which I am truly thankful, and without which this thesis would have been impossible. I would particularly like to thank my supervisor, Vincent Mirza, as well as my committee members Ari Gandsman and Julie LaPlante. I would also like to thank Arai Yusuke, Isaac Gagné and Alexis Truong for their support and advice during the completion of my thesis. -

Through the Case of Izumo Taishakyo Mission of Hawaii

The Japanese and Okinawan American Communities and Shintoism in Hawaii: Through the Case of Izumo Taishakyo Mission of Hawaii A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAIʽI AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN AMERICAN STUDIES MAY 2012 By Sawako Kinjo Thesis Committee: Dennis M. Ogawa, Chairperson Katsunori Yamazato Akemi Kikumura Yano Keywords: Japanese American Community, Shintoism in Hawaii, Izumo Taishayo Mission of Hawaii To My Parents, Sonoe and Yoshihiro Kinjo, and My Family in Okinawa and in Hawaii Acknowledgement First and foremost, I would like to express my deep and sincere gratitude to my committee chair, Professor Dennis M. Ogawa, whose guidance, patience, motivation, enthusiasm, and immense knowledge have provided a good basis for the present thesis. I also attribute the completion of my master’s thesis to his encouragement and understanding and without his thoughtful support, this thesis would not have been accomplished or written. I also wish to express my warm and cordial thanks to my committee members, Professor Katsunori Yamazato, an affiliate faculty from the University of the Ryukyus, and Dr. Akemi Kikumura Yano, an affiliate faculty and President and Chief Executive Officer (CEO) of the Japanese American National Museum, for their encouragement, helpful reference, and insightful comments and questions. My sincere thanks also goes to the interviewees, Richard T. Miyao, Robert Nakasone, Vince A. Morikawa, Daniel Chinen, Joseph Peters, and Jikai Yamazato, for kindly offering me opportunities to interview with them. It is a pleasure to thank those who made this thesis possible.