Journal of Arts & Humanities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

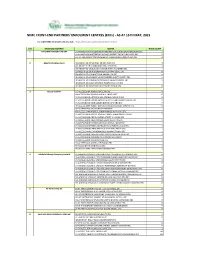

NIMC FRONT-END PARTNERS' ENROLMENT CENTRES (Ercs) - AS at 15TH MAY, 2021

NIMC FRONT-END PARTNERS' ENROLMENT CENTRES (ERCs) - AS AT 15TH MAY, 2021 For other NIMC enrolment centres, visit: https://nimc.gov.ng/nimc-enrolment-centres/ S/N FRONTEND PARTNER CENTER NODE COUNT 1 AA & MM MASTER FLAG ENT LA-AA AND MM MATSERFLAG AGBABIAKA STR ILOGBO EREMI BADAGRY ERC 1 LA-AA AND MM MATSERFLAG AGUMO MARKET OKOAFO BADAGRY ERC 0 OG-AA AND MM MATSERFLAG BAALE COMPOUND KOFEDOTI LGA ERC 0 2 Abuchi Ed.Ogbuju & Co AB-ABUCHI-ED ST MICHAEL RD ABA ABIA ERC 2 AN-ABUCHI-ED BUILDING MATERIAL OGIDI ERC 2 AN-ABUCHI-ED OGBUJU ZIK AVENUE AWKA ANAMBRA ERC 1 EB-ABUCHI-ED ENUGU BABAKALIKI EXP WAY ISIEKE ERC 0 EN-ABUCHI-ED UDUMA TOWN ANINRI LGA ERC 0 IM-ABUCHI-ED MBAKWE SQUARE ISIOKPO IDEATO NORTH ERC 1 IM-ABUCHI-ED UGBA AFOR OBOHIA RD AHIAZU MBAISE ERC 1 IM-ABUCHI-ED UGBA AMAIFEKE TOWN ORLU LGA ERC 1 IM-ABUCHI-ED UMUNEKE NGOR NGOR OKPALA ERC 0 3 Access Bank Plc DT-ACCESS BANK WARRI SAPELE RD ERC 0 EN-ACCESS BANK GARDEN AVENUE ENUGU ERC 0 FC-ACCESS BANK ADETOKUNBO ADEMOLA WUSE II ERC 0 FC-ACCESS BANK LADOKE AKINTOLA BOULEVARD GARKI II ABUJA ERC 1 FC-ACCESS BANK MOHAMMED BUHARI WAY CBD ERC 0 IM-ACCESS BANK WAAST AVENUE IKENEGBU LAYOUT OWERRI ERC 0 KD-ACCESS BANK KACHIA RD KADUNA ERC 1 KN-ACCESS BANK MURTALA MOHAMMED WAY KANO ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK ACCESS TOWERS PRINCE ALABA ONIRU STR ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK ADEOLA ODEKU STREET VI LAGOS ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK ADETOKUNBO ADEMOLA STR VI ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK IKOTUN JUNCTION IKOTUN LAGOS ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK ITIRE LAWANSON RD SURULERE LAGOS ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK LAGOS ABEOKUTA EXP WAY AGEGE ERC 1 LA-ACCESS -

SUBSTR DESCR International Schools NAMIBIA 002747

SUBSTR DESCR International Schools NAMIBIA 002747 University Of Namibia NEPAL 001252 Tribhuvan University NETHERLANDS 004215 A T College 002311 Acad Voor Gezondheidszorg 004215 Atc 004510 Baarns Lyceum 000109 Catholic University Tilburg 000107 Catholic University, Nijmegan 000101 Delft University Of Technology 002272 Dordrecht Polytech 004266 Eindhoven Sec Schl 000102 Eindhoven Univ Technology 002452 Enschede College 000108 Erasmus Univ Rotterdam 000100 Free Univ Amsterdam 002984 Haarlem Business School 000112 Institute Of Social Studies 000113 Int Inst Aero Survey& Space Sc 004751 Katholieke Scholengemeenschap 002461 Netherlands School Of Business 000114 Philips Int Inst Tech Studies 046294 Rijksuniversiteit Leiden 000115 Royal Tropical Institute 004152 Schola Europaea Bergensis 000104 State Univ Groningen 000105 State Univ Leiden 000106 State Univ Limburg 000110 State Univ Utrecht 002430 State University Of Utrecht 004276 Stedelijk Gymnasium 002543 Technische Hogeschool Rijswijk 003615 The British Sch /netherlands 002452 Twentse Academie Voor Fysiothe 000099 Univ Amsterdam 000103 University Of Twente 002430 University Of Utrecht 000111 Wageningen Agricultural Univ 002242 Wageningen Agricultural Univ NETHERLANDS ANTILLES 002476 Univ Netherlands Antilles NEW ZEALAND 000758 Lincoln Col Canterbury 000759 Massey Univ Palmerston 000756 The University Of Auckland 000757 Univ Canterbury 000760 Univ Otago 000762 Univ Waikato International Schools 000761 Victoria Univ Wellington NICARAGUA 000210 Univ Centroamericana 000209 Univ Na Auto Nicaragua -

P E E L C H R Is T Ian It Y , Is L a M , an D O R Isa R E Lig Io N

PEEL | CHRISTIANITY, ISLAM, AND ORISA RELIGION Luminos is the open access monograph publishing program from UC Press. Luminos provides a framework for preserving and rein- vigorating monograph publishing for the future and increases the reach and visibility of important scholarly work. Titles published in the UC Press Luminos model are published with the same high standards for selection, peer review, production, and marketing as those in our traditional program. www.luminosoa.org Christianity, Islam, and Orisa Religion THE ANTHROPOLOGY OF CHRISTIANITY Edited by Joel Robbins 1. Christian Moderns: Freedom and Fetish in the Mission Encounter, by Webb Keane 2. A Problem of Presence: Beyond Scripture in an African Church, by Matthew Engelke 3. Reason to Believe: Cultural Agency in Latin American Evangelicalism, by David Smilde 4. Chanting Down the New Jerusalem: Calypso, Christianity, and Capitalism in the Caribbean, by Francio Guadeloupe 5. In God’s Image: The Metaculture of Fijian Christianity, by Matt Tomlinson 6. Converting Words: Maya in the Age of the Cross, by William F. Hanks 7. City of God: Christian Citizenship in Postwar Guatemala, by Kevin O’Neill 8. Death in a Church of Life: Moral Passion during Botswana’s Time of AIDS, by Frederick Klaits 9. Eastern Christians in Anthropological Perspective, edited by Chris Hann and Hermann Goltz 10. Studying Global Pentecostalism: Theories and Methods, by Allan Anderson, Michael Bergunder, Andre Droogers, and Cornelis van der Laan 11. Holy Hustlers, Schism, and Prophecy: Apostolic Reformation in Botswana, by Richard Werbner 12. Moral Ambition: Mobilization and Social Outreach in Evangelical Megachurches, by Omri Elisha 13. Spirits of Protestantism: Medicine, Healing, and Liberal Christianity, by Pamela E. -

Federalism and Political Problems in Nigeria Thes Is

/V4/0 FEDERALISM AND POLITICAL PROBLEMS IN NIGERIA THES IS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS By Olayiwola Abegunrin, B. S, Denton, Texas August, 1975 Abegunrin, Olayiwola, Federalism and PoliticalProblems in Nigeria. Master of Arts (Political Science), August, 1975, 147 pp., 4 tables, 5 figures, bibliography, 75 titles. The purpose of this thesis is to examine and re-evaluate the questions involved in federalism and political problems in Nigeria. The strategy adopted in this study is historical, The study examines past, recent, and current literature on federalism and political problems in Nigeria. Basically, the first two chapters outline the historical background and basis of Nigerian federalism and political problems. Chapters three and four consider the evolution of federal- ism, political problems, prospects of federalism, self-govern- ment, and attainment of complete independence on October 1, 1960. Chapters five and six deal with the activities of many groups, crises, military coups, and civil war. The conclusions and recommendations candidly argue that a decentralized federal system remains the safest way for keeping Nigeria together stably. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF TABLES0.0.0........................iv LIST OF FIGURES . ..... 8.............v Chapter I. THE HISTORICAL BACKGROUND .1....... Geography History The People Background to Modern Government II. THE BASIS OF NIGERIAN POLITICS......32 The Nature of Politics Cultural Factors The Emergence of Political Parties Organization of Political Parties III. THE RISE OF FEDERALISM AND POLITICAL PROBLEMS IN NIGERIA. ....... 50 Towards a Federation Constitutional Developments The North Against the South IV. -

An Empirical Assessment of the Relationship Of

An International Multidisciplinary Journal, Ethiopia Vol. 7 (2), Serial No. 29, April, 2013:350-370 ISSN 1994-9057 (Print) ISSN 2070--0083 (Online) DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/afrrev.7i2.22 Adire in South-western Nigeria: Geography of the Centres Areo, Margaret Olugbemisola- Department of Fine and Applied Arts, Ladoke Akintola University of Technology, P. M. B 4000, Ogbomoso, Nigeria E-mail; [email protected] & Kalilu, Razaq Olatunde Rom - Department of Fine and Applied Arts, Ladoke Akintola University of Technology, P. M. B 4000, Ogbomoso, Nigeria E-mail; [email protected] Abstract Adire, the patterned dyed cloth is extant and is practiced in almost all Yoruba towns in Southwestern Nigeria. The art tradition is however preponderant in a few Yoruba towns to the extent that the names of these towns are traditionally inseparable with the Adire art tradition. With Western education, introduction of foreign religions, influence from other cultures, technique and technology, there is a shift in the producers of Adire, the training pattern, and even an evolution in the production centre. While Western education resulted in a shift from the hitherto traditional Copyright© IAARR 2013: www.afrrevjo.net 350 Indexed African Journals Online: www.ajol.info Vol. 7 (2) Serial No. 29, April, 2013 Pp.350-370 apprenticeship method to the study of the art in schools, unemployment gave birth to the introduction of training drives by government and non governmental parastatals. This study, a field research, is an appraisal of the factors that contributed to the vibrancy of the traditionally renowned centres, and how the newly evolved centres have in contemporary times contributed to the sustainability of the Adire art tradition. -

The Influence of the Kingship Institution on Olojo Festival in Ile-Ife: a Case Study of the Late Ooni Adesoji Aderemi

The Influence of the Kingship Institution on Olojo Festival in Ile-Ife: A Case Study of the Late Ooni Adesoji Aderemi by Akinyemi Yetunde Blessing [email protected] Institute of African Studies, University of Ibadan, Oyo state, Nigeria Abstract In this paper an attempt is made to examine the mythic narratives and ritual performances in olojo festival and to discuss the traditional involvement of the Ooni of Ife during the festivals, making reference to the late Ọợni Adesoji Adėrėmí. This paper also investigates the implication of local, national and international politics on the traditional festival in Ile-Ife. The importance of the study arrives as a result of the significance of the Ile-Ife amidst the Yoruba towns. More so, festivals have cultural significance that makes some unique turning point in the history of most Yoruba society. Ǫlợjợ festival serves as the worship of deities and a bridge between the society and the spiritual world. It is also a day to celebrate the re-enactment of time. Ǫlợjợ festival demands the full participation of the reigning Ọợni of Ife. The result of the field investigation revealed that the myth of Ǫlợjợ festival remains, but several changes have crept into the ritual process and performances during the reign of the late Adesoji Adėrėmí. The changes vary from the ritual time, space, actions and amidst the ritual specialists. It is found out that some factors which influence these changes include religious contestation, ritual modernization, economics and political change not at the neglect of the king’s involvement in the local, national and international politics which has given space for questioning the Yoruba kingship institution. -

CIDOB International Yearbook 2008 Keys to Facilitate the Monitoring Of

CIDOB International Yearbook 2008 Keys to facilitate the monitoring of the Spanish Foreign Policy and the International Relations in 2007 Country profile: Nigeria and its regional context Annex Biographies of main political leaders* (+34) 93 302 6495 - Fax. (+34) 93 302 2118 - [email protected] - [email protected] 302 2118 93 Fax. (+34) - 302 6495 93 (+34) - Calle Elisabets, 12 - 08001 Barcelona, España - Tel. España 08001 Barcelona, 12 - - Calle Elisabets, * These annexes have been done by Dauda Garuba, Senior Programme Officer at the Centre for Democracy and Development (CDD) in Nigeria, in collaboration with CIDOB Foundation. Fundación CIDOB CIDOB INTERNATIONAL YEARBOOK 2008 Nigeria and its regional context Biographies of main political leaders of Nigeria Abubakar Tafawa Balewa (1912 -1966) Prime minister 1960-1966 Sir Abubakar Tafawa Balewa, Nigeria’s first and only Prime Minister of independent Nigeria, was born in 1912 in Tafawa Balewa, present Bauchi State. He had early education at a Quranic School in Bauchi and also studied at the famous Katsina Teachers’ Training College between 1928 and 1933 before returning to Bauchi to teach at the Bauchi Middle School. He later became the headmaster of the school. He (along with Malam Aminu Kano) was among the few learned teachers who were selected in northern Nigeria to study at the University of London’s Institute of Education where he obtained a teacher’s certificate in History in 1944. On return from the UK, Sir Balewa was appointed an Inspector of Schools, a position he held before he joined partisan politics and got elected by the Bauchi Native Authority to the Northern Region House of Assembly in 1946. -

When Religion Cannot Stop Political Crisis in the Old Western Region of Nigeria: Ikire Under Historial Review

Instructions for authors, subscriptions and further details: http://rimcis.hipatiapress.com When Religion Cannot Stop Political Crisis in the Old Western Region of Nigeria: Ikire under Historial Review Matthias Olufemi Dada Ojo1 1) Crawford University of the Apostolic Faith Mission, Nigeria Date of publication: November 30th, 2014 Edition period: November 2014 – March 2015 To cite this article: Ojo, M.O.D. (2014). When Religion Cannot Stop Political Crisis in the Old Western Region of Nigeria: Ikire under Historial Review. International and Multidisciplinary Journal of Social Sciences, 3(3), 248-267. doi: 10.4471/rimcis.2014.39 To link this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.4471/rimcis.2014.39 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE The terms and conditions of use are related to the Open Journal System and to Creative Commons Attribution License (CC-BY). RIMCIS – International and Multidisciplinary Journal of Social Sciences Vol. 3 No.3 November 2014 pp. 248-267 When Religion Cannot Stop Political Crisis in the Old Western Region of Nigeria: Ikire under Historical Review Matthias Olufemi Dada Ojo Crawford University of the Apostolic Faith Mission Abstract Using historical events research approach and qualitative key informant interview, this study examined how religion failed to stop political crisis that happened in the old Western region of Nigeria. Ikire, in the present Osun State of Nigeria was used as a case study. The study investigated the incidences of killing, arson and exile that characterized the crisis in the town which served as the case study. It argued that the two prominent political figures which started the crisis failed to apply the religious doctrines of love, peace and brotherhood which would have solved the crisis before it spread to all parts of the Old Western Region of Nigeria and the entire nation. -

Political Party Defections by Elected Officers in Nigeria: Nuisance Or Catalyst for Democratic Reforms?

International Journal of Research in Humanities and Social Studies Volume 7, Issue 2, 2020, PP 11-23 ISSN 2394-6288 (Print) & ISSN 2394-6296 (Online) Political Party Defections by Elected Officers in Nigeria: Nuisance or Catalyst for Democratic Reforms? Enobong Mbang Akpambang, Ph.D1*, Omolade Adeyemi Oniyinde, Ph.D2 1Senior Lecturer and Acting Head, Department of Public Law, Ekiti State University, Ado-Ekiti, Nigeria 2Senior Lecturer and Acting Head, Department of Jurisprudence and International Law, Faculty of Law, Ekiti State University, Ado-Ekiti, Nigeria *Corresponding Author: Enobong Mbang Akpambang, Ph.D, Senior Lecturer and Acting Head, Department of Public Law, Ekiti State University, Ado-Ekiti, Nigeria. ABSTRACT The article interrogated whether defections or party switching by elected officers, both in Nigeria‟s executive and legislative arms of government, constitutes a nuisance capable of undermining the country‟s nascent democracy or can be treated as a catalyst to ingrain democratic reforms in the country. This question has become a subject of increasing concerns in view of the influx of defections by elected officers from one political party to the other in recent times, especially before and after election periods, without the slightest compunction. It was discovered in the article that though the Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria 1999 (as amended) has made significant provisions regarding prohibition of defection, except in deserving cases, yet elected officers go about „party-prostituting‟ with reckless abandon. The article concludes that political party defections by elected officers, if left unchecked, may amount to a nuisance capable of undermining the democratic processes in Nigeria in the long run. -

The Case of Nigerian Civil War Poetry

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by International Institute for Science, Technology and Education (IISTE): E-Journals Journal of Literature, Languages and Linguistics - An Open Access International Journal Vol.1 2013 The Literary Artist as a Mediator: the Case of Nigerian Civil War Poetry Ade Adejumo (Ph.D) Department of General Studies, Ladoke Akintola University of Technology P.M.B. 4000, Ogbomoso,Oyo State, Nigeria. e-mail: [email protected] Abstract This paper contends that there exists a paradoxical relationship between violence and conflictual situations on one hand, and the literary art on the other. While conflictual violence exerts tremendous strains on human relations, literary artists have often had their creative sensibilities fired by such conflicts. The above accounts for the emergence of the war-sired creative enterprise collectively referred to as war literature. These writers have used their art either as mere chronicles of the unfolding drama of blood and death or as interventionist art to preach peace and restoration of human values. Using the Nigerian experience, this paper does an examination of select corpus of poetry, which emanated from the Nigerian civil war experience. It isolates the messages of peace, which went a long way in not only pointing out the evils occasioned by war and conflict but also in suturing the broken ties of humanity while the war lasted. As our societies are becoming increasingly conflictual, our literary endeavours should also assume more social responsibilities in terms of conflict mitigation, prevention and promotion of global peace. This paper therefore envisions a new literary movement i.e. -

Accredited Observer Groups/Organisations for the 2011 April General Elections

ACCREDITED OBSERVER GROUPS/ORGANISATIONS FOR THE 2011 APRIL GENERAL ELECTIONS Further to the submission of application by Observer groups to INEC (EMOC 01 Forms) for Election Observation ahead of the April 2011 General Elections; the Commission has shortlisted and approved 291 Domestic Observer Groups/Organizations to observe the forthcoming General Elections. All successful accredited Observer groups as shortlisted below are required to fill EMOC 02 Forms and submit the full names of their officials and the State of deployment to the Election Monitoring and Observation Unit, INEC. Please note that EMOC 02 Form is obtainable at INEC Headquarters, Abuja and your submissions should be made on or before Friday, 25th March, 2011. S/N ORGANISATION LOCATION & ADDRESS 1 CENTER FOR PEACEBUILDING $ SOCIO- HERITAGE HOUSE ILUGA QUARTERS HOSPITAL ECONOMIC RESOURCES ROAD TEMIDIRE IKOLE EKITI DEVELOPMENT(CEPSERD) 2 COMMITTED ADVOCATES FOR SUSTAINABLE DEV SUITE 18 DANOVILLE PLAZA GARDEN ABUJA &YOUTH ADVANCEMENT FCT 3 LEAGUE OF ANAMBRA PROFESSIONALS 86A ISALE-EKO WAY DOLPHIN – IKOYI 4 YOUTH MOVEMENT OF NIGERIA SUITE 24, BLK A CYPRIAN EKWENSI CENTRE FOR ARTS & CULTURE ABUJA 5 SCIENCE & ECONOMY DEV. ORG. SUITE KO5 METRO PLAZA PLOT 791/992 ZAKARIYA ST CBD ABUJA 6 GLOBAL PEACE & FORGIVENESS FOUNDATION SUITE A6, BOBSAR COMPLEX GARKI 7 CENTRE FOR ACADEMIC ENRICHMENT 2 CASABLANCA ST. WUSE 11 ABUJA 8 GREATER TOMORROW INITIATIVE 5 NSIT ST, UYO A/IBOM 9 NIG. LABOUR CONGRESS LABOUR HOUSE CBD ABUJA 10 WOMEN FOR PEACE IN NIG NO. 4 MOHAMMED BUHARI WAY KADUNA 11 YOUTH FOR AGRICULTURE 15 OKEAGBE CLOSE ABUJA 12 COALITION OF DEMOCRATS FOR ELECTORAL 6 DJIBOUTI CRESCENT WUSE 11, ABUJA REFORMS 13 UNIVERSAL DEFENDERS OF DEMOCRACY UKWE HOUSE, PLOT 226 CENSUS CLOSE, BABS ANIMASHANUN ST. -

Money and Politics in Nigeria

Money and Politics in Nigeria Edited by Victor A.O. Adetula Department for International DFID Development International Foundation for Electoral System IFES-Nigeria No 14 Tennessee Crescent Off Panama Street, Maitama, Abuja Nigeria Tel: 234-09-413-5907/6293 Fax: 234-09-413-6294 © IFES-Nigeria 2008 This publication is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of International Foundation for Electoral System First published 2008 Printed in Abuja-Nigeria by: Petra Digital Press, Plot 1275, Nkwere Street, Off Muhammadu Buhari Way Area 11, Garki. P.O. Box 11088, Garki, Abuja. Tel: 09-3145618, 08033326700, 08054222484 ISBN: 978-978-086-544-3 This book was made possible by funding from the UK Department for International Development (DfID). The opinions expressed in this book are those of the individual authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of IFES-Nigeria or DfID. ii Table of Contents Acknowledgements v IFES in Nigeria vii Tables and Figures ix Abbreviations and Acronyms xi Preface xv Introduction - Money and Politics in Nigeria: an Overview -Victor A.O. Adetula xxvii Chapter 1- Political Money and Corruption: Limiting Corruption in Political Finance - Marcin Walecki 1 Chapter 2 - Electoral Act 2006, Civil Society Engagement and the Prospect of Political Finance Reform in Nigeria - Victor A.O. Adetula 13 Chapter 3 - Funding of Political Parties and Candidates in Nigeria: Analysis of the Past and Present - Ezekiel M. Adeyi 29 Chapter 4 - The Role of INEC, ICPC and EFCC in Combating Political Corruption - Remi E.