Beyond Programmatic Versus Patrimonial Politics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

P E E L C H R Is T Ian It Y , Is L a M , an D O R Isa R E Lig Io N

PEEL | CHRISTIANITY, ISLAM, AND ORISA RELIGION Luminos is the open access monograph publishing program from UC Press. Luminos provides a framework for preserving and rein- vigorating monograph publishing for the future and increases the reach and visibility of important scholarly work. Titles published in the UC Press Luminos model are published with the same high standards for selection, peer review, production, and marketing as those in our traditional program. www.luminosoa.org Christianity, Islam, and Orisa Religion THE ANTHROPOLOGY OF CHRISTIANITY Edited by Joel Robbins 1. Christian Moderns: Freedom and Fetish in the Mission Encounter, by Webb Keane 2. A Problem of Presence: Beyond Scripture in an African Church, by Matthew Engelke 3. Reason to Believe: Cultural Agency in Latin American Evangelicalism, by David Smilde 4. Chanting Down the New Jerusalem: Calypso, Christianity, and Capitalism in the Caribbean, by Francio Guadeloupe 5. In God’s Image: The Metaculture of Fijian Christianity, by Matt Tomlinson 6. Converting Words: Maya in the Age of the Cross, by William F. Hanks 7. City of God: Christian Citizenship in Postwar Guatemala, by Kevin O’Neill 8. Death in a Church of Life: Moral Passion during Botswana’s Time of AIDS, by Frederick Klaits 9. Eastern Christians in Anthropological Perspective, edited by Chris Hann and Hermann Goltz 10. Studying Global Pentecostalism: Theories and Methods, by Allan Anderson, Michael Bergunder, Andre Droogers, and Cornelis van der Laan 11. Holy Hustlers, Schism, and Prophecy: Apostolic Reformation in Botswana, by Richard Werbner 12. Moral Ambition: Mobilization and Social Outreach in Evangelical Megachurches, by Omri Elisha 13. Spirits of Protestantism: Medicine, Healing, and Liberal Christianity, by Pamela E. -

Conference Paper by Victor Egwemi

HERE WE GO AGAIN!: A DISCOURSE ON THE GALE OF DEFECTIONS INTO THE ALL PROGRESSIVE CONGRESS (APC) IN THE AFTERMATH OF THE 2015 GENERAL ELECTIONS IN NIGERIA BY Victor EGWEMI Department of Political Science Ibrahim Babangida University, Lapai [email protected] 08062908766 / 08084220830 Abstract In the aftermath of the 2015 general elections and the victory of the All Progressive Congress (APC) in the Presidential, National Assembly and Gubernatorial elections, there has been a gale of defections into the APC especially from members of the former ruling party the Peoples Democratic Party (PDP). This seems to be a reversal of roles for the two political parties. Before the 2015 elections, the PDP used to be the most attractive platform in the country. Most defections in the past used to be into the PDP. In fact the party had foisted on Nigerians an “if you can‟t beat them join them mentality”. However, with the victory of the APC and the impending (?) implosion of the PDP, the former has become the platform of choice in the country. What are the implications of the continuing opportunism of Nigerian politicians on the country‟s democratic health? What do the defections portend for the party system in the country? What measures can be put in place to stem the tide of opportunism in the country. After a successful fifth circle of elections is Nigeria finally on the road to a one party state? What happened to the PDP‟s aspiration to rule the country for 60 years? Will the APC take the position of the PDP as the largest political party in Africa? These are some of the questions that this paper will interrogate. -

PROVISIONAL LIST.Pdf

S/N NAME YEAR OF CALL BRANCH PHONE NO EMAIL 1 JONATHAN FELIX ABA 2 SYLVESTER C. IFEAKOR ABA 3 NSIKAK UTANG IJIOMA ABA 4 ORAKWE OBIANUJU IFEYINWA ABA 5 OGUNJI CHIDOZIE KINGSLEY ABA 6 UCHENNA V. OBODOCHUKWU ABA 7 KEVIN CHUKWUDI NWUFO, SAN ABA 8 NWOGU IFIONU TAGBO ABA 9 ANIAWONWA NJIDEKA LINDA ABA 10 UKOH NDUDIM ISAAC ABA 11 EKENE RICHIE IREMEKA ABA 12 HIPPOLITUS U. UDENSI ABA 13 ABIGAIL C. AGBAI ABA 14 UKPAI OKORIE UKAIRO ABA 15 ONYINYECHI GIFT OGBODO ABA 16 EZINMA UKPAI UKAIRO ABA 17 GRACE UZOME UKEJE ABA 18 AJUGA JOHN ONWUKWE ABA 19 ONUCHUKWU CHARLES NSOBUNDU ABA 20 IREM ENYINNAYA OKERE ABA 21 ONYEKACHI OKWUOSA MUKOSOLU ABA 22 CHINYERE C. UMEOJIAKA ABA 23 OBIORA AKINWUMI OBIANWU, SAN ABA 24 NWAUGO VICTOR CHIMA ABA 25 NWABUIKWU K. MGBEMENA ABA 26 KANU FRANCIS ONYEBUCHI ABA 27 MARK ISRAEL CHIJIOKE ABA 28 EMEKA E. AGWULONU ABA 29 TREASURE E. N. UDO ABA 30 JULIET N. UDECHUKWU ABA 31 AWA CHUKWU IKECHUKWU ABA 32 CHIMUANYA V. OKWANDU ABA 33 CHIBUEZE OWUALAH ABA 34 AMANZE LINUS ALOMA ABA 35 CHINONSO ONONUJU ABA 36 MABEL OGONNAYA EZE ABA 37 BOB CHIEDOZIE OGU ABA 38 DANDY CHIMAOBI NWOKONNA ABA 39 JOHN IFEANYICHUKWU KALU ABA 40 UGOCHUKWU UKIWE ABA 41 FELIX EGBULE AGBARIRI, SAN ABA 42 OMENIHU CHINWEUBA ABA 43 IGNATIUS O. NWOKO ABA 44 ICHIE MATTHEW EKEOMA ABA 45 ICHIE CORDELIA CHINWENDU ABA 46 NNAMDI G. NWABEKE ABA 47 NNAOCHIE ADAOBI ANANSO ABA 48 OGOJIAKU RUFUS UMUNNA ABA 49 EPHRAIM CHINEDU DURU ABA 50 UGONWANYI S. AHAIWE ABA 51 EMMANUEL E. -

1 CHAPTER ONE INTRODUCTION 1.1 Background to the Study the Nigeria Police Force (NPF) Was Established in 1930 As One of the Inst

CHAPTER ONE INTRODUCTION 1.1 Background to the Study The Nigeria Police Force (NPF) was established in 1930 as one of the institutions used in consolidating colonial rule through repressive tactics in maintenance of law and order (Jemibewon, 2001, Odinkalu, 2005,35: Okoigun, 2000, 2-3; Onyeozili, 2005, Rotimi, 2001:1; Tamuno, 1970). Commenting on the origin of the NPF, Nwolise, (2004: 73-74) notes that “the colonial masters deliberately recruited people one could call street and under-bridge men (area boys in today’s parlance) to establish the early Police Force…the police recruits were not properly trained…and where police officers were then trained with emphasis on human rights, the supremacy of the law and welfare of the community, the seeds of revolt may be sown which would grow within the police and extend to the wider society”. Nwolise particularly noted that there were disparities in Ireland, where Nigerian recruits were trained in military institutions to employ high-handed tactics on the people while their Irish counterparts were trained in a Police Academy to be civil and polite in their engagement with the people. As noted by Olurode (2010: 3) “the succeeding post-colonial state and its leading actors could not have been better schooled in the art of perdition, intrigues and abuse of state power…as they had experienced all possible lessons in subversion and derogation of people’s power”, expressed mainly through the infliction of repressive measures by security forces. Since independence, the NPF has struggled to institute reforms, which seem not to have led to a fundamental change in the strategic objectives, tactics and strategies of law enforcement (Alemika: 2013; Chukwuma, 2006). -

Agulu Road, Adazi Ani, Anambra State. ANAMBRA 2 AB Microfinance Bank Limited National No

LICENSED MICROFINANCE BANKS (MFBs) IN NIGERIA AS AT DECEMBER 29, 2017 # Name Category Address State Description 1 AACB Microfinance Bank Limited State Nnewi/ Agulu Road, Adazi Ani, Anambra State. ANAMBRA 2 AB Microfinance Bank Limited National No. 9 Oba Akran Avenue, Ikeja Lagos State. LAGOS 3 Abatete Microfinance Bank Limited Unit Abatete Town, Idemili Local Govt Area, Anambra State ANAMBRA 4 ABC Microfinance Bank Limited Unit Mission Road, Okada, Edo State EDO 5 Abestone Microfinance Bank Ltd Unit Commerce House, Beside Government House, Oke Igbein, Abeokuta, Ogun State OGUN 6 Abia State University Microfinance Bank Limited Unit Uturu, Isuikwuato LGA, Abia State ABIA 7 Abigi Microfinance Bank Limited Unit 28, Moborode Odofin Street, Ijebu Waterside, Ogun State OGUN 8 Abokie Microfinance Bank Limited Unit Plot 2, Murtala Mohammed Square, By Independence Way, Kaduna State. KADUNA 9 Abubakar Tafawa Balewa University Microfinance Bank Limited Unit Abubakar Tafawa Balewa University (ATBU), Yelwa Road, Bauchi Bauchi 10 Abucoop Microfinance Bank Limited State Plot 251, Millenium Builder's Plaza, Hebert Macaulay Way, Central Business District, Garki, Abuja ABUJA 11 Accion Microfinance Bank Limited National 4th Floor, Elizade Plaza, 322A, Ikorodu Road, Beside LASU Mini Campus, Anthony, Lagos LAGOS 12 ACE Microfinance Bank Limited Unit 3, Daniel Aliyu Street, Kwali, Abuja ABUJA 13 Acheajebwa Microfinance Bank Limited Unit Sarkin Pawa Town, Muya L.G.A Niger State NIGER 14 Achina Microfinance Bank Limited Unit Achina Aguata LGA, Anambra State ANAMBRA 15 Active Point Microfinance Bank Limited State 18A Nkemba Street, Uyo, Akwa Ibom State AKWA IBOM 16 Acuity Microfinance Bank Limited Unit 167, Adeniji Adele Road, Lagos LAGOS 17 Ada Microfinance Bank Limited Unit Agwada Town, Kokona Local Govt. -

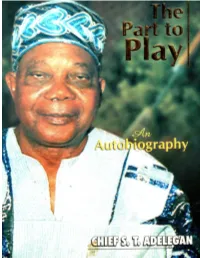

THE PART to PLAY an Autobiography

THE PART TO PLAY An Autobiography of Chief S. T. Adelegan Deputy-Speaker Western Region of Nigeria House of Assembly 1960-1965 The Story of the Life of a Nigerian Humanist, Patriot & Selfless Service i THE PART TO PLAY Author Shadrach Titus Adelegan Printing and Packaging Kingsmann Graffix Copyright: Terrific Investment & Consulting All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means mechanical photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the Author. Republished 2019 by: Terrific Investment & Consulting ISBN 30455-1-5 All enquiries to: [email protected], [email protected], ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Dedication iv Foreword v Introduction vi Chapter One: ANTECEDENTS 1 Chapter Two: MY EARLY YEARS 31 Chapter Three: AT ST ANDREWS COLLEGE, OYO 45 Chapter Four THE UNFORGETABLE ENCOUNTER WITH OONI ADESOJI ADEREMI 62 Chapter Five DOUBLE PROMOTION AT THE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE, IBADAN 73 Chapter Six NOW A GRADUATE TEACHER 86 Chapter Seven THE PRESSURE BY MY NATIVE COMMUNITY & MY DILEMMA 97 Chapter Eight THE COST OF PATRIOTISM & POLITICAL PERSECUTION 111 Chapter Nine: HOW WE BROKE THE MONOPOLY OF DR. NNAMDI AZIKIWE’S NCNC 136 Chapter Ten THE BEGINNING OF THE END OF THE FIRST REPUBLIC 156 Chapter Eleven THE FINAL COLLAPSE OF THE FIRST REPUBLIC - 180 Chapter Twelve COMMONWEALTH PARLIAMENTARY ASSOCIATION MEETING 196 Chapter Thirteen POLITICAL RELATIONSHIP 209 Chapter Fourteen SERVICE WITHOUT REMUNERATION 229 Chapter Fifteen TRIBUTES 250 Chapter Sixteen GOING FORWARD 275 Chapter Seventeen ABOUT THE AUTHOR 280 iii DEDICATION To God Almighty who has used me as an ass To be ridden for His Glory To manifest in the lives of people; And Also, To Humanity iv FOREWORD Shadrach Titus Adelegan, one of Nigeria’s astute politicians of the First Republic, and an outstanding educationist and community leader is one of the few Nigerians who have contributed in great and concrete terms to the development of humanity. -

I the GROWTH of POLITICAL AWARENESS IK NIGERIA By

i THE GROWTH OF POLITICAL AWARENESS IK NIGERIA by JAMES BERTIN WEBSTER B. A., University of British Columbia, I95& A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE PvEQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF Master of Arts in the Department of History We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITy OF BRITISH COLUMBIA April, I958 ii Abstract . Prior, to I9*+5, neither the majority of British nor Africans were convinced that Western parliamentary forms of government could be trans• ferred successfully to Nigeria. Generally it was considered that the Nigerian society would evolve from traditional forms of organization to something typically African which would prepare Africans for their event• ual full participation in the world society. After 19^5 under the stim• ulation of nationalism this concept of evolvement was completely abandoned in favour of complete adoption of Western institutions. It is to be ex• pected that after independence the conservative forces of African tradition• alism will revive and that a painful process of modification of Western institutions will begin. It would seem however, that modifications are not likely to be too fundamental if one can judge by the success with which Nigerians have handled these institutions and by the material advantages which political leaders have been able to bring to the people through them. The thesis is divided into three chapters. Chapter one is a condensa• tion of much research. It is intended to provide the background to the main body of the work. It describes the tribal, religious and economic differences in Nigeria which have been forces in Nigerian politics since 1920. -

Standing Committees of the 9Th Senate (2019-2023) (Chairmen and Vice Chairmen)

Standing Committees of the 9th Senate (2019-2023) (Chairmen and Vice Chairmen) S/N COMMITTEES CHAIRMAN VICE CHAIRMAN 1. Agriculture and Productivity Sen. Abdullahi Adamu Sen. Bima Mohammed Enagi 2. Air Force Sen Bala Ibn Na’allah Sen. Michael Ama Nnachi 3. Army Sen.Mohammed Ali Ndume Sen. Abba Patrick Moro 4. Anti-Corruption and Sen. Suleiman Kwari Sen. Aliyu Wamakko Financial Crimes 5. Appropriations Sen. Jibrin Barau Sen. Stella Oduah 6. Aviation Sen. Dino Melaye Sen. Bala Ibn Na’allah 7. Banking Insurance and Other Sen. Uba Sani Sen. Uzor Orji Kalu Financial Institutions 8. Capital Market Sen. Ibikunle Amosun Sen. Binos Dauda Yaroe 9. Communications Sen. Oluremi Tinubu Sen. Ibrahim Mohammed Bomai 10. Cooperation and integration Sen. Chimaroke Nnamani Sen. Yusuf Abubukar Yusuf in Africa and NEPAD 11. Culture and Tourism Sen. Rochas Okorocha Sen. Ignatius Datong Longjan 12. Customs, Excise and Tariff Sen. Francis Alimikhena Sen. Francis Fadahunsi 13. Defence Sen. Aliyu Wamakko Sen. Istifanus Dung Gyang 14. Diapsora and NGOs Sen. Surajudeen Ajibola Sen. Ibrahim Yahaya Basiru Oloriegbe 15. Downstream Petroleum Sen. Sabo Mohammed Sen. Philip Aduda Nakudu 16. Drugs and Narcotics Sen. Hezekiah Dimka Sen. Chimaroke Nnamani 17. Ecology and Climate Change Sen. Mohammed Hassan Sen. Olunbunmi Adetunmbi Gusau 18. Education (Basic and Sen. Ibrahim Geidam Sen. Akon Etim Eyakenyi Secondary) 19. Employment, Labour and Sen. Benjamin Uwajumogu Sen. Abdullahi Kabir Productivity Barkiya 20. Environment Sen. Ike Ekweremadu Sen. Hassan Ibrahim Hadeija 21. Establishment and Public Sen. Ibrahim Shekarau Sen. Mpigi Barinada Service 22. Ethics and Privileges Sen. Ayo Patrick Akinyelure Sen. Ahmed Baba Kaita 23. -

A Randomized Analysis of the 2015 General Elections and Peoples Democratic Party (PDP)

World Applied Sciences Journal 35 (4): 626-634, 2017 ISSN 1818-4952 © IDOSI Publications, 2017 DOI: 10.5829/idosi.wasj.2017.626.634 From Transformation Agenda to Tsunami Phenomenon: A Randomized Analysis of the 2015 General Elections and Peoples Democratic Party (PDP) Joseph Okwesili Nkwede Department of Political Science, Ebonyi State University, Abakaliki, Nigeria Abstract: Globally, elections have been the usual mechanism by which modern representative democracy has operated over the years. The universal use of elections as a tool for selecting representatives in modern democracies, describes the process of fair electoral systems. Essentially, the most important elements encapsulating the democratic agenda are popular participation, equitable representation and accountability. It is increasingly clear that democracy consists not only in winning elections but also in establishing organic relations with the people and allowing them to control their leaders by holding them accountable. In the developing democracies particularly in Nigeria, there are insinuations that the political gladiators always canverse and solicit for votes from the electorates and soon afterwards, abandon the electorates as they assume office in the guise that their political fortunes are divine and not challengeable by any human institution. Against this backdrop, this paper aims at interrogating the circumstances that characterized the 2015 general elections and the failure of the PDP Presidential aspirant. Indeed, this session is therefore devoted to the analysis of the 2015 general elections and the PDP misfortune in Nigeria. Key words: Elections Democracy Participation PDP and Nigeria INTRODUCTION sanctity, transparency and credibility of election results in the nation’s democratic setting [4]. This is so because Elections constitute an important element of there is empirical evidence over the years, which elections representative government. -

SENATE of the FEDERAL REPUBLIC of NIGERIA VOTES and PROCEEDINGS Wednesday, 24Th February, 2010

6TH NATIONAL ASSEMBLY THIRD SESSION No. 63 439 SENATE OF THE FEDERAL REPUBLIC OF NIGERIA VOTES AND PROCEEDINGS Wednesday, 24th February, 2010 1. The Senate met at 10.25 a.m. The Senate President read prayers. 2. Votesand Proceedings: The Senate President announced that he had examined the Votes and Proceedings of Tuesday, 23rd February, 2010 and approved same. By unanimous consent, the Votes and Proceedings were approved. 3. Messagesfrom the ActingPresident: The Senate President announced that he had received two letters from the Acting President, Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces of the Federation which he read as follows: (A) ACTING PRESIDENT, FEDERAL REPUBLIC OF NIGERIA SHIAg.P!SECI147113 22"" February, 2010 Distinguished Senator David Mark, GCON, President of the Senate, Senate Chambers, National Assembly Complex, Three Arms Zone, Abuja. PRINTED BY NATIONAL ASSEMBL Y PRESS, ABUJA 440 Wednesday, 24th February, 2010 No. 63 Your Excellency, UNIVERSAL SERVICE PROVISION FUND 2010 BUDGET PROPOSAL I write to forward for the kind consideration and approval of the Senate of the Federal Republic of Nigeria, the 2010 budget proposal of the Universal Service Provision Fund. Please accept the assurances of my highest consideration. Yours Sincerely, Signed: Dr. Goodluck E. Jonathan, GCON (B) ACTING PRESIDENT, FEDERAL REPUBLIC OF NIGERIA SHIAg.PISECIl47113 22'" February, 2010 Distinguished Senator David Mark, GCON, President of the Senate, Senate Chambers, National Assembly Complex, Three Arms Zone, Abuja. Your Excellency, NIGERIAN COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION 2010 BUDGET PROPOSAL I write to forward for the kind consideration and approval of the Senate of the Federal Republic of Nigeria, the 2010 budget proposal of the Nigerian Communications Commission. -

A History of the Republic of Biafra

A History of the Republic of Biafra The Republic of Biafra lasted for less than three years, but the war over its secession would contort Nigeria for decades to come. Samuel Fury Childs Daly examines the history of the Nigerian Civil War and its aftermath from an uncommon vantage point – the courtroom. Wartime Biafra was glutted with firearms, wracked by famine, and administered by a government that buckled under the weight of the conflict. In these dangerous conditions, many people survived by engaging in fraud, extortion, and armed violence. When the fighting ended in 1970, these survival tactics endured, even though Biafra itself disappeared from the map. Based on research using an original archive of legal records and oral histories, Daly catalogues how people navigated conditions of extreme hardship on the war front and shows how the conditions of the Nigerian Civil War paved the way for the long experience of crime that followed. samuel fury childs daly is Assistant Professor of African and African American Studies, History, and International Comparative Studies at Duke University. A historian of twentieth-century Africa, he is the author of articles in journals including Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History, African Studies Review, and African Affairs. A History of the Republic of Biafra Law, Crime, and the Nigerian Civil War samuel fury childs daly Duke University University Printing House, Cambridge CB2 8BS, United Kingdom One Liberty Plaza, 20th Floor, New York, NY 10006, USA 477 Williamstown Road, Port Melbourne, VIC 3207, Australia 314 321, 3rd Floor, Plot 3, Splendor Forum, Jasola District Centre, New Delhi 110025, India 79 Anson Road, #06 04/06, Singapore 079906 Cambridge University Press is part of the University of Cambridge. -

The Sixth National Assembly and Constitutional Amendment in Nigeria- a New Era Or a Fait Accompli? Hassan I

Scholars International Journal of Law, Crime and Justice Abbreviated Key Title: Sch Int J Law Crime Justice ISSN 2616-7956 (Print) |ISSN 2617-3484 (Online) Scholars Middle East Publishers, Dubai, United Arab Emirates Journal homepage: https://scholarsmepub.com/sijlcj/ Review Article The Sixth National Assembly and Constitutional Amendment in Nigeria- A New Era or a Fait Accompli? Hassan I. Adebowale* Senior Lecturer Department of Private Property Law, Adeleke University, Ede, Osun State DOI: 10.36348/SIJLCJ.2019.v02i10.005 | Received: 15.10.2019 | Accepted: 22.10.2019 | Published: 27.10.2019 *Corresponding author: Hassan I. Adebowale Abstract The history of constitutional development in Nigeria reveals the tortuous road the legislators have taken to bestow a legacy of a befitting Constitution. Constitutional provisions on amendment are tedious, and sometimes, manifestly insurmountable. It therefore behoves the National Assembly to painstakingly adhere to the various provisions of the Constitution in order to fill the lacunae in the Nigeria corpus juris which has constantly plagued the country‟s political, judicial and socio-economic sectors. From the colonial era, it has always been the same story of exploring different types of constitution. This “try and error” approach has never yielded any acceptable grundnorm for the Federal Government of Nigeria. The peculiar composition of Nigeria as a multilingual, multi-culture and religiously diversified country has virtually been cited as the key issue in Nigeria‟s tortuous road to a satisfactory constitutional achievement. The much touted “unity in diversity” has proved to be nothing more than political slogan. With the pervasive cry for restructuring in Nigeria, and the continuous failure of successive governments to find sustainable solutions to the yearnings and cravings of the citizenry, this writer looks back at where it all went wrong.