World Bank Document

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

La Privatización Y Desguace Del Sistema Ferroviario Argentino Durante El Modelo De Acumulación Neoliberal

La privatización y desguace del sistema ferroviario argentino durante el modelo de acumulación neoliberal Nombre completo autor: Franco Alejandro Pagano Pertenencia institucional: Universidad Nacional de Cuyo Correo electrónico: [email protected] Mesa temática: Nº 6: Sociología Económica: las correlaciones de fuerzas en los cambios de los patrones acumulación del capital. Disciplinas: Ciencia política y administración pública. Sociología. Palabras claves: Privatización, neoliberalismo, ferrocarriles, transporte, modelo de acumulación, éxodo rural. Resumen: En Argentina, a partir de 1976, el sistema industrial y productivo del país sufrió fuertes transformaciones a partir de la implementación del paradigma neoliberal imperante a nivel internacional. Este cambio estructural, implementado de forma gradual, alteró también -conjuntamente a las relaciones de producción- la dinámica social, laboral, educacional e institucional del país, imprimiendo una lógica capitalista a todo el accionar humano. Como parte de ello se dio en este periodo el proceso de concesiones, privatización y cierre de la mayoría de los ramales ferroviarios que poseía el país, modificando hasta nuestros días la concepción de transporte y perjudicando seriamente al colectivo nacional. De las graves consecuencias que esto produjo trata este trabajo. Ponencia: 1.0 Golpe de Estado de 1976. Etapa militar del neoliberalismo El golpe cívico-militar del 24 de marzo de 1976 podría reconocerse como la partida de nacimiento del neoliberalismo en la Argentina, modelo económico que se implementará por medio la fuerza -buscando el disciplinamiento social- con terror y violencia. Se iniciaba así un nuevo modelo económico basado en la acumulación 1 rentística y financiera, la apertura irrestricta, el endeudamiento externo y el disciplinamiento social” (Rapoport, 2010: 287-288) Como ya sabemos este nuevo modelo de acumulación comprende un conjunto de ideas políticas y económicas retomadas del liberalismo clásico: el ya famoso laissez faire, laissez passer. -

Privatesector

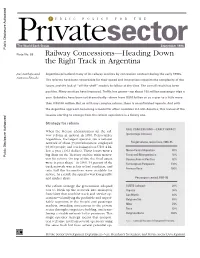

P UBLIC POLICYsector FOR THE TheP World Bankrivate Group September 1996 Public Disclosure Authorized Note No. 88 Railway Concessions—Heading Down the Right Track in Argentina José Carbajo and Argentina privatized many of its railway services by concession contract during the early 1990s. Antonio Estache The reforms have been remarkable for their speed and innovation—despite the complexity of the issues and the lack of “off-the-shelf” models to follow at the time. The overall result has been positive. Many services have improved. Traffic has grown—up about 180 million passenger trips a year. Subsidies have been cut dramatically—down from US$2 billion or so a year to a little more than US$100 million. But as with any complex reform, there is an unfinished agenda. And with Public Disclosure Authorized the Argentine approach becoming a model for other countries in Latin America, this review of the lessons starting to emerge from the reform experience is a timely one. Strategy for reform RAIL CONCESSIONS—EARLY IMPACT When the Menem administration set the rail- way reform in motion in 1990, Ferrocarriles (percentage increase) Argentinos, the largest operator, ran a national network of about 35,000 kilometers, employed Freight volume, major lines, 1990–95 92,000 people, and was losing about US$1.4 bil- lion a year (1992 dollars). These losses were a Nuevo Central Argentino 40% big drain on the Treasury and the main motiva- Ferrocarril Mesopotámico 50% Public Disclosure Authorized tion for reform. On top of this, the fixed assets Buenos Aires al Pacífico 92% were in poor shape—in 1990, 54 percent of the Ferroexpreso Pampeano 130% track network was in fair or bad condition, and Ferrosur Roca 160% only half the locomotives were available for service. -

Master Document Template

Copyright by Katherine Schlosser Bersch 2015 The Dissertation Committee for Katherine Schlosser Bersch Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: When Democracies Deliver Governance Reform in Argentina and Brazil Committee: Wendy Hunter, Co-Supervisor Kurt Weyland, Co-Supervisor Daniel Brinks Bryan Jones Jennifer Bussell When Democracies Deliver Governance Reform in Argentina and Brazil by Katherine Schlosser Bersch, B.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin August 2015 Acknowledgements Many individuals and institutions contributed to this project. I am most grateful for the advice and dedication of Wendy Hunter and Kurt Weyland, my dissertation co- supervisors. I would also like to thank my committee members: Daniel Brinks, Bryan Jones, and Jennifer Bussell. I am particularly indebted to numerous individuals in Brazil and Argentina, especially all of those I interviewed. The technocrats, government officials, politicians, auditors, entrepreneurs, lobbyists, journalists, scholars, practitioners, and experts who gave their time and expertise to this project are too many to name. I am especially grateful to Felix Lopez, Sérgio Praça (in Brazil), and Natalia Volosin (in Argentina) for their generous help and advice. Several organizations provided financial resources and deserve special mention. Pre-dissertation research trips to Argentina and Brazil were supported by a Lozano Long Summer Research Grant and a Tinker Summer Field Research Grant from the University of Texas at Austin. A Boren Fellowship from the National Security Education Program funded my research in Brazil and a grant from the University of Texas Graduate School provided funding for research in Argentina. -

Estudios Sobre Planificación Sectorial Y Regional

ISSN 2591-3654 ESTUDIOS SOBRE PLANIFICACIÓN SECTORIAL Y REGIONAL DICIEMBRE 2017 Año 2 N° 4 Logística. Temas de Agenda Secretaría de Política Económica Estudios sobre Planificación Sectorial y Regional ESTUDIOS SOBRE PLANIFICACIÓN SECTORIAL Y REGIONAL DICIEMBRE 2017 INDICE Introducción…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….…………… 4 Sistema ferroviario de cargas. Caracterización y desafíos de la política pública ……………………..……………… 5 Bitrenes. Su implementación en Argentina ….......................................................................................... 36 Costos logísticos. La incidencia del flete interno en las operaciones de exportación…………………………….. 50 Esta serie de informes tiene por objeto realizar una descripción analítica y específica sobre temáticas de particular relevancia para la planificación del desarrollo productivo sectorial y regional del país. Se consideran temáticas transversales como: empleo, innovación, educación, tecnología, desarrollo regional, inserción internacional, entre otros aspectos de relevancia. Publicación propiedad del Ministerio de Hacienda de la Nación. Director Dr. Mariano Tappatá. Registro DNDA en trámite. Hipólito Yrigoyen 250 Piso 8° (C1086 AAB) Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires – República Argentina. Tel: (54 11) 4349-5945 y 5918. Correo electrónico: [email protected] URL: http://www.minhacienda.gob.ar SUBSECRETARIA DE PROGRAMACIÓN MICROECONÓMICA Dirección Nacional de Planificación Sectorial - Dirección Nacional de Planificación Regional ESTUDIOS SOBRE PLANIFICACIÓN SECTORIAL Y REGIONAL -

World Bank Document

Document of The World Bank FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY Public Disclosure Authorized Report No: 50467-AR PROJECT APPRAISAL DOCUMENT ON A Public Disclosure Authorized PROPOSED LOAN IN THE AMOUNT OF US$150 MILLION TO THE ARGENTINE REPUBLIC FOR A Public Disclosure Authorized METROPOLITAN AREAS URBAN TRANSPORT PROJECT (PTUMA) IN SUPPORT OF THE FIRST PHASE OF A METROPOLITAN AREAS URBAN TRANSPORT PROGRAM September 18, 2009 Sustainable Development Department Argentina, Chile Paraguay, Uruguay Country Management Unit Latin America and the Caribbean Region Public Disclosure Authorized This document has a restricted distribution and may be used by recipients only in the performance of their official duties. Its contents may not otherwise be disclosed without World Bank authorization. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (Exchange Rate Effective September 10th, 2009) Currency Unit = AR Peso AR$1.00 = US$0.26 US$1.00 = AR$ 3.84 FISCAL YEAR January 1 – December 31 ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS AADT Annual Average Daily Traffic AFP Public auto- transport for passengers AGN Argentine Supreme Auditing Institution (Auditoría General de la Nación) AMBA Buenos Aires Metropolitan Area (Area Metropolitana de Buenos Aires) APL Adaptable Program Loan BNA Banco de la Nacion Argentina BRT Bus Rapid Transit CAS Country Assistance Strategy CAP Community Health Centers CCP Compensaciones Complementarias Provinciales CDCT Coeficiente de Distribución de Compensaciones Tarifarias CFAA Country Financial Accountablility Assessment CNG Compressed Natural Gas CNRT National Transport Regulatory -

Transportation Infrastructure Opportunities for US Business

Argentina: Transportation Infrastructure Opportunities for U.S. Business 1 Our Presenters Chargé d’Affaires Tom Minister of Transportation CEO Alejandro Diaz Cooney Guillermo Dietrich American Chamber of U.S. Embassy Buenos Government of Argentina Commerce in Argentina Aires Status of the National Transport Plan and its impact on the development of the country ROADS FREIGHT RAILWAYS CHALLENGES ACROSS THE TRANSPORT SECTOR • 40% of the network in poor conditions • 5% the total freight • 95% of freight transported by truck. • Average speed: 14km/hour PORTS AND WATERWAYS AIR SECTOR URBAN MOBILITY • Limitations on infrastructure don’t • Low domestic connectivity. • 15M users in MRBA. • Half the number of pax/capita than allow the operation of large ships. • Absence of public transport in the in the rest of the region. • Lack of access infrastructure. provinces • Space for improvements in security • Loss of competitiveness. and air traffic control. • Low quality infrastructure. VISION Carrying out the most ambitious Transport Plan in the history of the country, with a federal vision; integrated and intermodal transport that provides conditions of excellence for the mobility of people and goods; reduces transportation times, costs and negative externalities; and fundamentally maximizes safety, comfort and sustainability. STRATEGIC GOALS INFRAESTRUCTURE Transforming, developing and modernizing the infraestructure for transport in the country, through a federal strategy, improving the connectivity and productivity of the regional economies, especially the ones that have been most left behind. PRIORIZATION Managing in an efficient and sustainable way the different modes of transport, to contribute to the economic growth and to reduce the logistic costs, defending the interests of users. -

Ministerio De Transporte

https://www.boletinoficial.gob.ar/#!DetalleNorma/246112/20210628 MINISTERIO DE TRANSPORTE Resolución 211/2021 RESOL-2021-211-APN-MTR Ciudad de Buenos Aires, 25/06/2021 VISTO el Expediente N° EX-2019-72754431- -APN-CERC#MTR, las Leyes N° 19.550 (t.o. 1984), N° 22.520 (t.o. Decreto N° 438/92), N° 26.352 y N° 27.132, el Decreto de Necesidad y Urgencia N° 566 de fecha 21 de mayo de 2013, los Decretos N° 1144 de fecha 14 de junio de 1991, N° 994 de fecha 18 de junio de 1992, N° 2681 de fecha 29 de diciembre de 1992, N° 82 de fecha 3 de febrero de 2009, N° 1039 de fecha 5 de agosto de 2009, N° 2017 de fecha 25 de noviembre de 2008, N° 1924 de fecha 16 de septiembre de 2015, N° 367 de fecha 16 de febrero de 2016, N° 1027 de fecha 7 de noviembre de 2018, N° 50 de fecha 19 de diciembre de 2019, N° 335 de fecha 4 de abril de 2020 y N° 532 de fecha 9 de junio de 2020, las Resoluciones N° 336 de fecha 15 de junio de 1990, N° 5 de fecha 23 de enero de 1991, N° 145 de fecha 31 de enero de 1992 todas ellas del ex MINISTERIO DE OBRAS Y SERVICIOS PUBLICOS, N° 469 de fecha 30 de mayo de 2013 del ex MINISTERIO DEL INTERIOR Y TRANSPORTE, N° 182 de fecha 14 de julio de 2016 y N° 139 de fecha 12 de junio de 2020 ambas del MINISTERIO DE TRANSPORTE, la Disposición N° 219 de fecha 29 de marzo de 2021 de la COMISIÓN NACIONAL DE REGULACION DEL TRANSPORTE; y CONSIDERANDO: Que por el Decreto N° 1144 de fecha 14 de junio de 1991 se aprobó el Contrato de Concesión para la explotación del sector de la Red Ferroviaria Nacional denominado “Corredor Rosario - Bahía Blanca”, con las firmas FERROEXPRESO PAMPEANO S.A. -

Olympic Champion Rio’S New Light Railway Set to Expand

Dec Cover:Layout 1 21/11/2016 14:10 Page 1 December 2016 I Volume 56 Issue 12 www.railjournal.com | @railjournal IRJInternational Railway Journal Points of the future Open for competition New-generation of turnouts NTV and the benefits of open- reduces maintenance costs access high-speed in Italy Olympic champion Rio’s new light railway set to expand Dec Cover:Layout 1 21/11/2016 14:10 Page 1 December 2016 I Volume 56 Issue 12 www.railjournal.com | @railjournal IRJInternational Railway Journal Points of the future Open for competition New-generation of turnouts NTV and the benefits of open- reduces maintenance costs access high-speed in Italy Olympic champion Rio’s new light railway set to expand IRJDECXX (Schaeffler1):Layout 1 16/11/2016 09:05 Page 1 Mobility for Tomorrow In an increasingly dynamic world, bearings and system solutions from Schaeffler not only help railways prepare for the challenges of the future, but also improve their safety. • Thanks to the cost-efficiency of our application solutions, you can make lasting savings in terms of your overall costs. • We constantly test the reliability of our components in our inde- pendent Schaeffler Railway Testing Facility for rolling bearings. • We manage the entire lifecycle of our products, right up to railway bearing reconditioning with certification. We have been a development partner for the sector for more than 100 years. Use our engineering expertise! Dec Contents:Layout 1 21/11/2016 17:01 Page 3 Contents Contact us December 2016 Volume 56 issue 12 Editorial offices News Post -

Los Ferrocarriles De Carga En Argentina - 14 De Diciembre De 2015

Los ferrocarriles de carga en argentina - 14 de Diciembre de 2015 Economía Los ferrocarriles de carga en argentina A principios de los ’90 se concesionó la explotación de los ferrocarriles de carga en nuestro país. La red concesionada es la siguiente (datos al 2007). a) Ferroexpreso Pampeano: 5.119 espacio kilómetros, de los que 1.910 km pertenecen a la red troncal y 3.209 km al resto de la red. b) Nuevo Central Argentino: 4.750 kilómetros, de los 1.620 km pertenecen a la red troncal y 3.130 km al resto de la red. c) Ferrosur Roca: 3.145 kilómetros, de los cuales1.251 km pertenecen a la red troncal y 1.894 km al resto de la red. d) ALL Central: 5.690 kilómetros, de los cuales 1.884 km pertenecen a la red troncal y 3.806 km al resto de la red. e) ALL Mesopotámico: 2.704 kilómetros, de los cuales 1.128 pertenecen a la red troncal y 1.576 al resto de la red. f) Belgrano Cargas: 7.347 kilómetros, de los cuales 5.053 pertenecen a la red troncal y 2.294 km al resto de la red. En total la red está constituida por 28.755 kilómetros, de los cuales 12.846 km pertenecen a la red troncal y 15.909 km al resto de la red. Veamos en primer lugar como ha sido el desempeño de los ferrocarriles de cargas en los últimos años (siempre hay que tener presente que cuando se concesionaron las distintas líneas al sector privado, a principios de los ’90, los ferrocarriles transportaban 8 millones de toneladas): 2002 17,4 millones tn 2003 20,6 millones tn 2004 21,7 millones tn 2995 23,4 millones tn 2006 24,0 millones tn 2007 24,9 millones tn 2008 23,9 millones tn 2009 20,7 millones tn Veamos la cifra del 2009 por ferrocarril: a) Ferroexpreso Pampeano: transportó 2,95 millones de toneladas. -

Supply of ATS System to the Suburban Railway Network of Buenos Aires, Argentina

May 22, 2017 Marubeni Corporation Supply of ATS System to the Suburban Railway Network of Buenos Aires, Argentina Japan Bank for International Cooperation (“JBIC”) and Argentinian Government have signed a Loan Agreement on May 19, 2017 to provide a financial loan for a contract between Marubeni Corporation (“Marubeni”) and Argentinian Railway (Administración de Infraestructuras Ferroviarias S. E., “ADIF”) to supply an ATS (Automatic Train Stop) system to the suburban railway network of Buenos Aires. Marubeni will supply the ATS system manufactured by Nippon Signal Co., Ltd. (“Nippon Signal”) for the 280 trains of the suburban lines. Since President Macri took office in December 2015, a large-scale infrastructure plan has been developed and the Government is actively inviting foreign investment in the country. Thus in 2016 during the summit meeting between Prime Minister Abe and President Marci of Argentina one of the topics discussed was the promotion of Japanese technology export with the support of JBIC and Nippon Export and Investment Insurance (”NEXI”). The contract between Marubeni and ADIF is a real example of such efforts of the two Governments, where JBIC is co-financing the project with Deutsche Bank AG, Tokyo Branch (“Deutsche Bank”), and NEXI is providing insurance for the loan. Marubeni in its turn has a track record of supplying ATS systems in 1981 and 2015, both times for the Roca Line which has the largest volume of passengers per year. These have contributed to the safe operation of the railway for more than 30 years. In the near future, with the new ATS system installed across the whole suburban network, the safety and the accuracy of railway operations will be substantially improved. -

El SISTEMA FERROVIARIO DE LA REPÚBLICA ARGENTINA

Revista Geográfica Digital. IGUNNE. Facultad de Humanidades. UNNE. Año 10. Nº 19. Enero-Junio 2013. ISSN 1668-5180 Resistencia, Chaco El SISTEMA FERROVIARIO DE LA REPÚBLICA ARGENTINA CÁTEDRA: GEOGRAFÍA ARGENTINA PROF. ANÍBAL MARCELO MIGNONE 2012 Publicado en formato digital: Prof. Aníbal Marcelo MIGNONE. El SISTEMA FERROVIARIO DE LA REPÚBLICA ARGENTINA. Resúmenes. Revista Geográfica Digital. IGUNNE. Facultad de Humanidades. UNNE. Año 10. Nº 19. Enero-Junio 2013. ISSN 1668-5180. Resistencia, Chaco. En: http://hum.unne.edu.ar/revistas/geoweb/default.htm Revista Geográfica Digital. IGUNNE. Facultad de Humanidades. UNNE. Año 10. Nº 19. Enero-Junio 2013. ISSN 1668-5180 Resistencia, Chaco LOS INICIOS • Revisar la historia del sistema ferroviario argentino implica remontarse al 29 de agosto de 1857 cuando un conjunto de empresarios construyeron la primera línea ferroviaria. El recorrido iba desde Plaza Lavalle hasta San José de Flores. Posteriormente, iba desde el centro de la ciudad de Buenos Aires hasta los suburbios, a lo largo de 10 km. Primera locomotora “La Porteña” Fuente: elmagazindemerlo.blogspot.com.ar Publicado en formato digital: Prof. Aníbal Marcelo MIGNONE. El SISTEMA FERROVIARIO DE LA REPÚBLICA ARGENTINA. Resúmenes. Revista Geográfica Digital. IGUNNE. Facultad de Humanidades. UNNE. Año 10. Nº 19. Enero-Junio 2013. ISSN 1668-5180. Resistencia, Chaco. En: http://hum.unne.edu.ar/revistas/geoweb/default.htm Revista Geográfica Digital. IGUNNE. Facultad de Humanidades. UNNE. Año 10. Nº 19. Enero-Junio 2013. ISSN 1668-5180 Resistencia, Chaco Entre 1862 y 1883 nacen cuatro líneas: • Ferrocarril del Oeste (posteriormente Domingo F. Sarmiento) fue el primero en entrar en funcionamiento para cubrir (inicialmente) la distancia entre plaza Lavalle y Floresta, en Buenos Aires. -

Intercity and Buenos Aires Access Roads

Report No. 14469-AR Argentina TransportPrivatization and Regulation: The Next Wave of Challenges Public Disclosure Authorized June 6, 1996 Infrastructure Division C-ountrvDepartment I Latin America and the Caribbean Regional Office Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Documentof the World Bank Public Disclosure Authorized FISCAL YEAR January I to December 31 WEIGHTS AND MEASURES The Metric System is used throughout this report CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS Currency Unit - Argentine Peso (A$) US$ = A$1 ACRONYMS AGP = Administration General de Puertos ATAM = Autoridad de Transporte del Area Metropolitana BA = Buenos Aires BOT = Build Operate and Transfer CVF = Consejo Vial Federal DNCPVN = Direcci6n Nacional de Construcciones Portuarias y Vias Navegables DNV = Departamento Nacional de Vialidad DPV = Direcci6n Provincial de Vialidad FA = Ferrocarriles Argentinos FEMESA = Ferrocarriles Metropolitanos S. A. FONAVI = Fondo Nacional de Vivienda FONDOVIAL Fondo Nacional de Vialidad FP = Ferroexpreso Pampeno GOA = Government of Argentina JNG = Junta Nacional de Granos NRT Net Registered Tons OECD = Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development SAP = Sociedad de Administraci6n Portuaria SAR = Staff Appraisal Report SBASE = Subterraneos de Buenos Aires S. E. SUBTE = The Metropolitan Suburban Rail Services of Buenos Aires PREFACE This report has been prepared by a team led by Antonio Estache (LA1IN) based on the findings of two missions that visited Argentina in January 9-17, 1995 and January 29-February 11, 1995. The first mission included Jose Carbajo (TWUTD), Jose G6mez- Ibanez (Harvard University) and John Meyers (Harvard University). The second included Antonio Estache (LAIN), Marianne Fay (Young Professional), Walter Garcia-Fontes (Univesitat Pompeu Fabra, Barcelona), Frannie Humplick (PRDEI), and Thomas-Olivier Nasser (MIT and Institut d'Economie Industrielle, Toulouse).