Departamento De Economía

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Políticas Ferroviarias En La Argentina. Planes Y Proyectos En La Primera Década Del Siglo Xxi

Revista Transporte y Territorio /10 (2014) ISSN 1852-7175 13 Políticas ferroviarias en la argentina. Planes y proyectos en la primera década del siglo XXI Mariana Schweitzer " CONICET - Centro de Estudios Hábitat y Municipio, Facultad de Arquitectura Diseño y Urbanismo, Universidad de Buenos Aires Recibido: 29 de junio de 2012. Aceptado: 27 de mayo de 2013 Resumen En el presente trabajo se identifica, se analiza y se compara, los planes y proyectos Palabras clave que se han formulado en la última década y que involucran al transporte ferroviario Políticas ferroviarias en la Argentina, propuestos desde esferas nacionales y desde organismos suprana- Ferrocarriles cionales. Para las acciones desarrolladas desde el nivel nacional se han analizado el Planes y proyectos Plan Nacional de Inversiones Ferroviarias, PLANIFER (2004-2007), el Programa de Obras indispensables en materia de transporte ferroviario de pasajeros (2005), el Plan Palavras-chave Estratégico Territorial en sus avances del año 2008 y del año 2011 y las Bases para Política ferroviária la elaboración del Plan Quinquenal de Transporte, sometidas a discusión a partir Ferrovias de noviembre del año 2011. A nivel supranacional, se analizaron los proyectos de la Planos e projetos Iniciativa para la Integración de la Infraestructura Regional Sudamericana, IIRSA. El análisis se complementa con la reflexión sobre las obras que han avanzado en relación con dichos planes. Abstract Railway policies in argentina. Plans and projects in the 1st decade of the xxi century. Key words This work identifies, analyzes and compares plans and projects carried out in the last Rail policy decade involving railway transport in Argentina, proposed by national and interna- Railways tional organizations. -

Ministerio De Economía Y Finanzas Públicas Secretaría De Política Económica Subsecretaría De Coordinación Económica Dirección Nacional De Inversión Pública

MINISTERIO DE ECONOMÍA Y FINANZAS PÚBLICAS SECRETARÍA DE POLÍTICA ECONÓMICA SUBSECRETARÍA DE COORDINACIÓN ECONÓMICA DIRECCIÓN NACIONAL DE INVERSIÓN PÚBLICA SISTEMA DE TRANSPORTE FERROVIARIO: ESCENARIOS FUTUROS Y SU IMPACTO EN LA ECONOMÍA PRÉSTAMO BID 1896/OC-AR PROYECTO DINAPREI 1.EE.517 Juan Alberto ROCCATAGLIATA Juan BASADONNA Javier MARTÍNEZ HERES Pablo GARCÍA Santiago BLANCO INFORME FINAL TOMO I BUENOS AIRES Índice TOMO I RESUMEN EJECUTIVO 3 INTRODUCCIÓN 29 A. EL SISTEMA DE TRANSPORTE, UNA VISIÓN DE CONJUNTO 36 B. ESTADO DE SITUACIÓN ACTUAL, DEL CUADRO SITUACIONAL ACTUAL AL REDISEÑO DEL SISTEMA 65 C. EXPLICACIÓN DEL PLAN “SISTEMA FERROVIARIO ARGENTINO 2025” IDENTIFICACIÓN DE LOS POSIBLES ESCENARIOS FUTUROS DESDE UNA VISIÓN ESTRATÉGICA 69 D. DIRECTRICES ESTRATÉGICAS PARA EL MODELO FERROVIARIO ARGENTINO, HORIZONTE 2025 81 E. COMPONENTES DEL SISTEMA A SER PENSADO Y DISEÑADO 162 1. Contexto institucional para la reorganización y gestión del sistema ferroviario. 2. Rediseño y reconstrucción de las infraestructuras ferroviarias de la red de interés federal. 3. Sistema de transporte de cargas. Intermodalidad y logística. 4. Sistema interurbano de pasajeros de largo recorrido. 5. Sistema de transporte metropolitano de cercanías de la metápolis de Buenos Aires y en otras aglomeraciones del país. 6. Desarrollo industrial ferroviario de apoyo al plan. F. ESCENARIOS PROPUESTOS 173 Programas, proyectos y actuaciones priorizados. TOMO II G. IDENTIFICACIÓN DE LOS PROGRAMAS, PROYECTOS Y ACTUACIONES 193 Análisis de demanda y proyección de la oferta TOMO III H. EVALUACIÓN AMBIENTAL ESTRATÉGICA 351 I. IMPACTO EN EL NIVEL DE EMPLEO, PBI Y RETORNO FISCAL 463 2 RESUMEN EJECUTIVO 3 DIAGNÓSTICO Del cuadro situacional actual al rediseño del sistema No es intención del presente trabajo realizar un diagnóstico clásico de la situación actual del sistema ferroviario argentino. -

La Privatización Y Desguace Del Sistema Ferroviario Argentino Durante El Modelo De Acumulación Neoliberal

La privatización y desguace del sistema ferroviario argentino durante el modelo de acumulación neoliberal Nombre completo autor: Franco Alejandro Pagano Pertenencia institucional: Universidad Nacional de Cuyo Correo electrónico: [email protected] Mesa temática: Nº 6: Sociología Económica: las correlaciones de fuerzas en los cambios de los patrones acumulación del capital. Disciplinas: Ciencia política y administración pública. Sociología. Palabras claves: Privatización, neoliberalismo, ferrocarriles, transporte, modelo de acumulación, éxodo rural. Resumen: En Argentina, a partir de 1976, el sistema industrial y productivo del país sufrió fuertes transformaciones a partir de la implementación del paradigma neoliberal imperante a nivel internacional. Este cambio estructural, implementado de forma gradual, alteró también -conjuntamente a las relaciones de producción- la dinámica social, laboral, educacional e institucional del país, imprimiendo una lógica capitalista a todo el accionar humano. Como parte de ello se dio en este periodo el proceso de concesiones, privatización y cierre de la mayoría de los ramales ferroviarios que poseía el país, modificando hasta nuestros días la concepción de transporte y perjudicando seriamente al colectivo nacional. De las graves consecuencias que esto produjo trata este trabajo. Ponencia: 1.0 Golpe de Estado de 1976. Etapa militar del neoliberalismo El golpe cívico-militar del 24 de marzo de 1976 podría reconocerse como la partida de nacimiento del neoliberalismo en la Argentina, modelo económico que se implementará por medio la fuerza -buscando el disciplinamiento social- con terror y violencia. Se iniciaba así un nuevo modelo económico basado en la acumulación 1 rentística y financiera, la apertura irrestricta, el endeudamiento externo y el disciplinamiento social” (Rapoport, 2010: 287-288) Como ya sabemos este nuevo modelo de acumulación comprende un conjunto de ideas políticas y económicas retomadas del liberalismo clásico: el ya famoso laissez faire, laissez passer. -

Privatesector

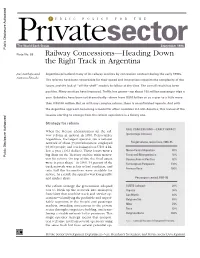

P UBLIC POLICYsector FOR THE TheP World Bankrivate Group September 1996 Public Disclosure Authorized Note No. 88 Railway Concessions—Heading Down the Right Track in Argentina José Carbajo and Argentina privatized many of its railway services by concession contract during the early 1990s. Antonio Estache The reforms have been remarkable for their speed and innovation—despite the complexity of the issues and the lack of “off-the-shelf” models to follow at the time. The overall result has been positive. Many services have improved. Traffic has grown—up about 180 million passenger trips a year. Subsidies have been cut dramatically—down from US$2 billion or so a year to a little more than US$100 million. But as with any complex reform, there is an unfinished agenda. And with Public Disclosure Authorized the Argentine approach becoming a model for other countries in Latin America, this review of the lessons starting to emerge from the reform experience is a timely one. Strategy for reform RAIL CONCESSIONS—EARLY IMPACT When the Menem administration set the rail- way reform in motion in 1990, Ferrocarriles (percentage increase) Argentinos, the largest operator, ran a national network of about 35,000 kilometers, employed Freight volume, major lines, 1990–95 92,000 people, and was losing about US$1.4 bil- lion a year (1992 dollars). These losses were a Nuevo Central Argentino 40% big drain on the Treasury and the main motiva- Ferrocarril Mesopotámico 50% Public Disclosure Authorized tion for reform. On top of this, the fixed assets Buenos Aires al Pacífico 92% were in poor shape—in 1990, 54 percent of the Ferroexpreso Pampeano 130% track network was in fair or bad condition, and Ferrosur Roca 160% only half the locomotives were available for service. -

Redalyc.Argentina, ¿País Sin Ferrocarril? La Dimensión Territorial

Revista Transporte y Territorio E-ISSN: 1852-7175 [email protected] Universidad de Buenos Aires Argentina Benedetti, Alejandro Argentina, ¿país sin ferrocarril? La dimensión territorial del proceso de reestructuración del servicio ferroviario (1957, 1980 y 1998) Revista Transporte y Territorio, núm. 15, 2016, pp. 68-85 Universidad de Buenos Aires Buenos Aires, Argentina Disponible en: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=333047931005 Cómo citar el artículo Número completo Sistema de Información Científica Más información del artículo Red de Revistas Científicas de América Latina, el Caribe, España y Portugal Página de la revista en redalyc.org Proyecto académico sin fines de lucro, desarrollado bajo la iniciativa de acceso abierto Revista Transporte y Territorio /15 (2016) ISSN 1852-7175 68 [68-85] Argentina, ¿país sin ferrocarril? La dimensión territorial del proceso de reestructuración del servicio ferroviario (1957, 1980 y 1998)* Alejandro Benedetti " CONICET/Instituto de Geografía, Facultad de Filosofía y Letras, Universidad de Buenos Aires, Argentina Resumen Desde inicios de la década de 1990 en Argentina se han implementado un conjunto de políticas tendientes a la liberalización y desregulación de la economía y a la privatización de activos del Estado. Esto incluyó la concesión de servicios ferroviarios, cuyo proceso comenzó en 1991. La privatización del ferrocarril suscitó cambios estructurales tanto en las pautas de organización del servicio como en las dimensiones de la infraestructura habilitada. Si bien este proceso de transformación tuvo gran repercusión en su momento, es notable la escasez de información existente sobre su magnitud. Esta investigación se propuso construir una serie de indicadores a través de los cuales se podría medir las transformaciones territoriales ocurridas tras la concesión del servicio a las empresas particulares y a los estados provinciales. -

Laszewicki, Alex Subsidios Y Acumulación Privada En El Trasporte

IX Jornadas de Sociología de la UNLP Laszewicki, Alex Subsidios y acumulación privada en el trasporte ferroviario metropolitano de Buenos Aires, 2003-2010 Introducción: contexto, pertinencia y objeto de la investigación. El período contenido entre los años 2002-2010 presentó una recuperación de la actividad económica tras la crisis de la convertibilidad que detonó la rebelión popular de diciembre de 2001, y que acabó en el fin de la paridad cambiaria en el año 2002. Así como esta crisis, en la posconvertibilidad las explicaciones acerca de las principales tendencias macroeconómicas tuvieron como uno de sus ejes centrales el análisis de las políticas del Estado nacional argentino. Con el avance del período se multiplicaron los análisis acerca de los cambios, pero también las continuidades en términos de política estatal en comparación al período anterior. La cuestión de las privatizadas y los subsidios fue problematizada al inicio del período, en el que recibieron ingentes sumas de dinero en un contexto de crisis económica y social para mantener niveles tarifarios bajos (Azpiazu y Schorr, 2003), pero más aún a partir de los años 2008/2009 con la llegada de los efectos de la crisis internacional y los resultados del denominado “conflicto del campo”. Caída de las reservas, aparición de resultados totales deficitarios en las cuentas públicas y deterioro del tipo de cambio alto fueron diferentes indicadores de la aparición de límites al tipo de desarrollo económico ocurrido en los años de crecimiento, cuestionando el “ciclo virtuoso” que parecía desprenderse del sostenimiento del triángulo superávit comercial-superávit fiscal-tipo de cambio “alto” (Eskenazi, 2009). -

Revista Del Centro De Estudios De Sociología Del Trabajo Nº6/2014 Paradojas Del Sistema Ferroviario Argentino (Pp

Paradojas del sistema ferroviario argentino: reflexiones en torno a la confiabilidad y la vulnerabilidad en una línea metropolitana Natalia L. Gonzalez1 Resumen * El riesgo y la seguridad del transporte ferroviario de pasajeros en la Argentina regresaron al centro de la escena a partir de los accidentes ocurridos desde 2011, evidenciando el deterioro de la infraestructura ferroviaria y material rodante, las fallas en la gestión y en el funcionamiento de las líneas. Se analizan los elementos asociados a la vulnerabilidad y confiabilidad del sistema ferroviario focalizando el caso de la línea Belgrano Sur. Se señalan las representaciones sociales sobre el riesgo que los trabajadores ferroviarios construyen de manera contradictoria con las manifestadas por la opinión pública. Así, el factor humano considerado por el mainstream del análisis de accidentes como una fuente indiscutible de la vulnerabilidad, se presenta como una de las fuentes de la confiabilidad. Palabras clave: gestión del riesgo, confiabilidad, prácticas de conductores de locomotoras, línea férrea metropolitana, Belgrano Sur, vulnerabilidad, representaciones sociales. Paradoxes of the Argentine Railway System: Reflexions regarding Reliability and Vulnerability of one City Route Abstract The debate about risk and safety of train passengers reappeard in Argentina after 2011 as a consequence of the major accidents that occurred since then. These accidents revealed both the deteriorated condition of roads and tractive equipment, and failures in management and Fecha de recepción : 23/12/2013 – Fecha de aceptación: 25/02/2014 1 Investigadora-docente, Universidad Nacional de General Sarmiento. Argentina. Email [email protected] * Agradezco los pertinentes comentarios de los evaluadores de este trabajo. 112 Natalia Gonzalez operation of the lines. -

Descargar Archivo

C E S P A Centro de Estudios de la Situación y Perspectivas de la Argentina ISSN 1853-7073 ANTE UN NUEVO CICLO: DELINEANDO UN FUTURO PARA EL FERROCARRIL INTERURBANO EN LA ARGENTINA1 Alberto Müller - CESPA-FCE-UBA DOCUMENTO DE TRABAJO Nro. 42 Junio 2015 1 Lautaro Chittaro colaboró con el acopio de información para este trabajo, y revisó una versión anterior. 1 1. OBJETIVO: EL FERROCARRIL ANTE UNA NUEVA ETAPA .......................................... 4 2. 60 AÑOS DE ACTIVIDAD FERROVIARIA: UNA BREVE RETROSPECTIVA ............... 6 i. Cuatro décadas de gestión estatal ........................................................................................ 7 a) 1948-1958 – Transición y definición institucional ............................................................................. 8 b) 1958-1975 – El programa desarrollista ........................................................................................... 12 c) 1976-1983 – Redireccionamiento y ajuste ...................................................................................... 17 d) 1983-1989 – Debacle y fin ............................................................................................................... 21 ii. El nuevo ciclo privado ............................................................................................................ 23 a) Las concesiones de carga ................................................................................................................ 26 b) El ferrocarril metropolitano ............................................................................................................ -

CAMPOS JIMENEZ Evaluating Rail Reform in LAC.D

I Conference on Railroad Industry Structure, Competition and Investment. Toulouse 7-8 November 2003 Evaluating rail reform in Latin America: Competition and investment effects* Javier CAMPOS** Juan Luis JIMÉNEZ Workgroup on Infrastructure and Transport Economics Department of Applied Economics University of Las Palmas - Spain Abstract Building on the existing literature and the new data emerged in recent years, this paper discusses the results of the rail restructuring experiences of Latin America countries during the 1990s. We critically evaluate how rail services and infrastructures were transferred from Government hands to private operators, particularly in the three largest economies in the region: Mexico, Brazil and Argentina. The paper analyzes the reasons behind the restructuring decisions and, but is mostly centered on the policy results, which are evaluated focusing on the competition and investment effects on investment decisions. The main purpose of this paper is to draw core lessons in order to provide governments with better information related to how they could structure a reform package in transport to make the best of the growth opportunities within their countries. This should help bring about the economic growth that is central in helping to alleviate poverty in developing countries and moving these economies out of the stagnation that they currently face. * This paper has been prepared for the 1st Conference on Railroad Industry Structure, Competition and Investment (Toulouse, 7-8 November, 2003). The authors acknowledge the contributions from previous studies and the help of the Brazilian government. However, the usual disclaimer applies. ** Contact author: Department of Applied Economics. University of Las Palmas. 4, Saulo Torón. -

Estudios Sobre Planificación Sectorial Y Regional

ISSN 2591-3654 ESTUDIOS SOBRE PLANIFICACIÓN SECTORIAL Y REGIONAL DICIEMBRE 2017 Año 2 N° 4 Logística. Temas de Agenda Secretaría de Política Económica Estudios sobre Planificación Sectorial y Regional ESTUDIOS SOBRE PLANIFICACIÓN SECTORIAL Y REGIONAL DICIEMBRE 2017 INDICE Introducción…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….…………… 4 Sistema ferroviario de cargas. Caracterización y desafíos de la política pública ……………………..……………… 5 Bitrenes. Su implementación en Argentina ….......................................................................................... 36 Costos logísticos. La incidencia del flete interno en las operaciones de exportación…………………………….. 50 Esta serie de informes tiene por objeto realizar una descripción analítica y específica sobre temáticas de particular relevancia para la planificación del desarrollo productivo sectorial y regional del país. Se consideran temáticas transversales como: empleo, innovación, educación, tecnología, desarrollo regional, inserción internacional, entre otros aspectos de relevancia. Publicación propiedad del Ministerio de Hacienda de la Nación. Director Dr. Mariano Tappatá. Registro DNDA en trámite. Hipólito Yrigoyen 250 Piso 8° (C1086 AAB) Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires – República Argentina. Tel: (54 11) 4349-5945 y 5918. Correo electrónico: [email protected] URL: http://www.minhacienda.gob.ar SUBSECRETARIA DE PROGRAMACIÓN MICROECONÓMICA Dirección Nacional de Planificación Sectorial - Dirección Nacional de Planificación Regional ESTUDIOS SOBRE PLANIFICACIÓN SECTORIAL Y REGIONAL -

Turismo, Patrimônio Cultural E Transporte Ferroviário

Universidade de São Paulo Programa de Pós-Graduação em Integração da América Latina Thiago Allis Turismo, patrimônio cultural e transporte ferroviário Um estudo sobre ferrovias turísticas no Brasil e na Argentina São Paulo 2006 Universidade de São Paulo Programa de Pós-Graduação em Integração da América Latina Thiago Allis Turismo, patrimônio cultural e transporte ferroviário. Um estudo sobre ferrovias turísticas no Brasil e na Argentina São Paulo 2006 Thiago Allis Turismo, patrimônio cultural e transporte ferroviário. Um estudo sobre ferrovias turísticas no Brasil e na Argentina Dissertação de mestrado apresentada ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em Integração da América Latina da Universidade de São Paulo como requisito parcial para a obtenção do título de Mestre em Integração da América Latina. Orientadora: Profa. Dra. Rebeca Scherer São Paulo 2006 Folha de Aprovação Thiago Allis Turismo, patrimônio cultural e transporte ferroviário. Um estudo sobre ferrovias turísticas no Brasil e na Argentina Dissertação de mestrado apresentada ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em Integração da América Latina da Universidade de São Paulo como requisito parcial para a obtenção do título de Mestre em Integração da América Latina. Aprovada em 1o de junho de 2006. Banca examinadora Orientadora: Profa. Dra. Rebeca Scherer Instituição: Universidade de São Paulo Profa. Dra. Sueli Teresinha Ramos Schiffer Instituição:Universidade de São Paulo Prof. Dr: Ricardo Hernán Medrano Instituição: Universidade Presbiteriana Mackenzie Agradecimentos Mesmo sendo perigoso confiar na memória, faço questão de agradecer, nominalmente, a uma série de pessoas que me ajudaram no decorrer do trabalho e da minha vida acadêmica e pessoal: à toda minha família, pelo apoio incondicional e pela paciência; à minha orientadora, Profa. -

Nota Breve Nro.22 C E S

C E S P A Centro de Estudios de la Situación y Perspectivas de la Argentina Alberto Müller Nota Breve Nro.22 Marzo de 2015 Av. Córdoba 2122 2do. Piso, Departamentos Pedagógicos (C 1120 AAQ) Ciudad de Buenos Aires Tel.: 54-11-4370-6183 – E-mail: [email protected] http://www.econ.uba.ar/cespa www.blogdelcespa.blogspot.com El reciente anuncio de creación de la empresa Ferrocarriles Argentinos Sociedad del Estado es un jalón simbólico de una cuarta etapa en la compleja historia del ferrocarril argentino. Las tres anteriores fueron el período predominantemente privado “clásico” (que duró grosso modo 80 años, de 1870 a 1950), los 40 años de explotación totalmente estatal (1950-1990) y las dos décadas de concesión privada (y en menor medida provincialización). Fue así que pasamos de un ferrocarril diversificado y “grande”, con cerca de 43.000 km de líneas, a uno más “pequeño” y especializado en pasajeros urbanos y cargas masivas, con algo más de 25.000 km. Esta hipotética cuarta etapa (son los historiadores los que decidirán sobre esto) fue delineándose en una larga transición: En 2004 caducó la concesión de la Línea San Martín a la empresa Metropolitano, entonces de Sergio Taselli. Siguieron las líneas Roca y Belgrano Sur, de la misma empresa; y, accidente de Once mediante, Trenes de Buenos Aires (líneas Mitre y Sarmiento), en 2012. La Provincia del Chaco transfirió en 2010 su operadora de pasajeros SEFECHA al Estado Nacional. El Ferrocarril Belgrano Cargas volvió al Estado en 2013 (luego de una trayectoria tortuosa) A ella se sumaron las cargueras San Martín y Urquiza, que fueron estatizadas tras el abandono de la concesionaria brasileña América Latina Logística.