Looking for Larvae: Collecting Data on Overwintering Insects

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Milk Thistle

Forest Health Technology Enterprise Team TECHNOLOGY TRANSFER Biological Control BIOLOGY AND BIOLOGICAL CONTROL OF EXOTIC T RU E T HISTL E S RACHEL WINSTON , RICH HANSEN , MA R K SCH W A R ZLÄNDE R , ER IC COO M BS , CA R OL BELL RANDALL , AND RODNEY LY M FHTET-2007-05 U.S. Department Forest September 2008 of Agriculture Service FHTET he Forest Health Technology Enterprise Team (FHTET) was created in 1995 Tby the Deputy Chief for State and Private Forestry, USDA, Forest Service, to develop and deliver technologies to protect and improve the health of American forests. This book was published by FHTET as part of the technology transfer series. http://www.fs.fed.us/foresthealth/technology/ On the cover: Italian thistle. Photo: ©Saint Mary’s College of California. The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, sex, religion, age, disability, political beliefs, sexual orientation, or marital or family status. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA’s TARGET Center at 202-720-2600 (voice and TDD). To file a complaint of discrimination, write USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, Room 326-W, Whitten Building, 1400 Independence Avenue, SW, Washington, D.C. 20250-9410 or call 202-720-5964 (voice and TDD). USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer. The use of trade, firm, or corporation names in this publication is for information only and does not constitute an endorsement by the U.S. -

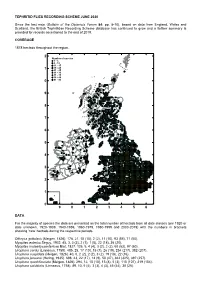

Tephritid Flies Recording Scheme June 2020

TEPHRITID FLIES RECORDING SCHEME JUNE 2020 Since the last note (Bulletin of the Dipterists Forum 84: pp. 8-10), based on data from England, Wales and Scotland, the British Tephritidae Recording Scheme database has continued to grow and a further summary is provided for records ascertained to the end of 2019. COVERAGE 1878 hectads throughout the region. 2 Number of species 1 - 5 6 - 10 11 - 15 1 16 - 20 21 - 25 26 - 30 31 - 35 36 - 40 0 41 - 45 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 0 9 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 DATA For the majority of species the data are presented as the total number of hectads from all date classes (pre 1920 or date unknown, 1920-1939, 1940-1959, 1960-1979, 1980-1999 and 2000-2019) with the numbers in brackets showing ‘new’ hectads during the respective periods. Dithryca guttularis (Meigen, 1826). 178, 21, 10 (10), 2 (2), 11 (10), 93 (85), 71 (50). Myopites eximius Séguy, 1932. 45, 3, 3 (3), 2 (1), 1 (0), 22 (18), 36 (20). Myopites inulaedyssentericae Blot, 1827. 126, 5, 4 (4), 3 (2), 2 (2), 60 (53), 97 (60). Urophora cardui (Linnaeus, 1758). 485, 25, 17 (10), 15 (7), 26 (19), 254 (217), 382 (207). Urophora cuspidata (Meigen, 1826). 40, 0, 2 (2), 2 (2), 3 (2), 19 (18), 22 (16). Urophora jaceana (Hering, 1935). 698, 43, 22 (17), 14 (9), 50 (47), 362 (325), 397 (257). Urophora quadrifasciata (Meigen, 1826). 294, 12, 15 (10), 13 (8), 5 (3), 115 (107), 219 (154). Urophora solstitialis (Linnaeus, 1758). -

Deer Mouse Predation on the Biological Control Agent, Urophora Spp., Introduced to Control Spotted Knapweed

This file was created by scanning the printed publication. Errors identified by the software have been corrected; however, some errors may remain. NORTHWESTERN NATURALIST 80:26-29 SPRING 1999 DEER MOUSE PREDATION ON THE BIOLOGICAL CONTROL AGENT, UROPHORASPP., INTRODUCED TO CONTROL SPOTTED KNAPWEED D. E. PEARSON USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Forestry Sciences Laboratory, 800 East Beckwith Avenue, Missoula, Montana 59801 USA ABSTRACT-Field observations made in 1993 suggested that rodents were preying on spotted knapweed (Centaurea maculosa) seedheads, possibly targeting the gall fly larvae (Urophoraspp.) which overwinter within them. I conducted a brief study to determine the cause of seedhead predation and quantify gall fly predation. Stomachs were examined from 19 deer mice (Pero- myscus maniculatus) captured in the fall of 1993 and winter of 1997. All individuals had preyed upon gall fly larvae. The mean number of gall fly larvae found in 10 deer mouse stomachs in the winter of 1997 was 212.8. The minimum number of larvae consumed by these 10 animals for 1 night of foraging was 2686. Availability of a concentrated protein that is a readily accessible and abundant resource during winter may elevate deer mouse populations in knapweed-in- fested habitats. Increases in densities of deer mice due to gall fly presence could bring about shifts in composition of small mammal communities. Key words: Peromyscus maniculatus, Urophora,Centaurea maculosa, deer mouse, gall fly, spot- ted knapweed, predation, biological control Spotted knapweed (Centaurea maculosa) is 1 0.8 to 9.3 galls per seedhead (Story and Now- of the fastest-spreading rangeland weeds in ierski 1984). -

Agent Name Here)

9999999999 Urophora quadrifasciata (Meig.) INVASIVE SPECIES ATTACKED: Black knapweed (Centaurea nigra) Brown knapweed (C. jacea) Diffuse knapweed (C. diffusa) Meadow knapweed (C. debauxii) Spotted knapweed (C. biebersteinii) TYPE OF AGENT: Seed feeding fly COLLECTABILITY: Mass ORIGIN: Eurasia DESCRIPTION AND LIFE CYCLE Adult: The flies measure 1 - 3 mm long. They have black bodies and clear wings distinctly marked with a black 'UV' pattern. At rest, the adult will hold their wings in a tented formation similar to a 'V'. Females can be identified by their long, pointed, black ovipositor. Adults emerge in late June and July, which coincides with the development of the knapweed flower buds, and mating begins immediately. Females start to lay eggs in three days and will continue to do so for three weeks. Eggs are laid into the unopened flower buds that are more mature than those preferred by Urophora affinis. U. quadrifasciata can oviposit and develop in the same flower heads as U. affinis, but avoid doing so because of the misshapen or delayed bud development that occurs with U. affinis attack. When they do co-exist, they do so without harming the other. Second generation adults appear in mid to late August and will mate and oviposit. Adults are capable of dispersing 21 km in five years. Fig. 1. U. quadrifasciata adult (credit Powell et al. 1994) Egg: The eggs incubate for 3 - 4 days. Larva: Creamy, white larvae penetrate into the flower bud and grow into a plump, 'barrel-like' shape. The entire larvae and pupae stages develop within galls inside the flower bud. -

Diptera, Tephritidae)

Zoodiversity, 54(6): 439–452, 2020 Fauna and Systematics DOI 10.15407/zoo2020.06.439 UDC 595.773(64) THE FRUIT FLIES OF MOROCCO: NEW RECORDS OF THE TEPHRITINAE (DIPTERA, TEPHRITIDAE) Y. El Harym1, B. Belqat1, V. A. Korneyev2,3 1Department of Biology, Faculty of Sciences, University Abdelmalek Essaâdi, Tétouan, Morocco E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] 2Schmalhausen Institute of Zoology NAS of Ukraine, vul. B. Khmelnytskogo, 15, Kyiv, 10030 Ukraine E-mail: [email protected] 3Corresponding author Y. El Harym (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6852-6602) B. Belqat (https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2857-7699) V. A. Korneyev (https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9631-1038) Th e Fruit Flies of Morocco: New Records of the Tephritinae (Diptera, Tephritidae). El Harym, Y., Belqat, B. & Korneyev, V. A. — Based on the samples of true fruit fl ies belonging to the subfamily Teph- ritinae collected in Morocco during 2016–2020, the genus Chaetostomella Hendel, 1927 and the species Myopites cypriaca Hering, 1938, M. longirostris (Loew, 1846), Tephritis carmen Hering, 1937 and Uro- phora jaculata Rondani, 1870 are recorded for the fi rst time in North Africa and Chaetorellia succinea Costa, 1844, Chaetostomella cylindrica Robineau-Desvoidy, 1830, Terellia luteola (Wiedemann, 1830), Terellia oasis (Hering, 1938) and Urophora quadrifasciata algerica (Hering, 1941) are new records for the Moroccan fauna. Th e occurrence of Capitites ramulosa (Loew, 1844), Tephritis simplex Loew, 1844 and Aciura coryli (Rossi, 1794) are confi rmed. Host plants as well as photos of verifi ed species are provided. Key words: Tephritidae, Tephritinae, Morocco, Middle Atlas, Rif, new records, host plants. -

Diptera, Tephritidae) of Fars Province, Iran

© Biologiezentrum Linz/Austria; download unter www.biologiezentrum.at Linzer biol. Beitr. 43/2 1229-1235 19.12.2011 Introduction to the Fruit Flies fauna (Diptera, Tephritidae) of Fars province, Iran M. FAZEL, M. FALLAHZADEH & M. GHEIBI A b s t r a c t : Data are given on the distribution of 16 species belonging to the Tephritidae (subfamilies Dacinae, Tephritinae and Trypetinae) that were collected by the first author in Fars province, Iran, during 2009-2010. Urophora cuspidata (MEIGEN 1826), Urophora kasachstanica (RICHTER 1964) and Chaetorellia jaceae (ROBINEAU- DESVOIDY 1830) are herein presented as a new to the Iranian fauna. Locality and date of collection, host(s) and distribution data for each species are provided. Key words: Diptera, Distribution, Fars province, Fruit flies, Iran, New records, Tephritidae. Introduction Tephritidae are picture-winged flies of variable size and belonging to the superfamily Tephritoidea within the suborder Brachycera. (DE MEYER 2006). The Tephritidae com- prise one of the largest and most abundant acalyptrate Diptera families worldwide of present day insects. The more than 4.400 species of fruit flies (family Tephritidae) in- clude numerous species important to agriculture as plant pests and biological control agents of noxious weeds. Other species are important as model organisms used for va- rious scientific studies, ranging from genetics and evolutionary biology to ecology (NORRBOM 2004, NORRBOM & CONDON 2010). The faunistic and taxonomic papers treated the family Tephritidae in Iran accumulated rapidly through last years (GHARALI et al. 2006, KARIMPOUR & MERZ 2006, GILASIAN & MERZ 2008, MOHAMMADZADE NAMIN & RASOULIAN 2009, MOHAMMADZADE NAMIN et al. 2010, ZARGHANI et al. -

Chapter 12. Biocontrol Arthropods: New Denizens of Canada's

291 Chapter 12 Biocontrol Arthropods: New Denizens of Canada’s Grassland Agroecosystems Rosemarie De Clerck-Floate and Héctor Cárcamo Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, Lethbridge Research Centre 5403 - 1 Avenue South, P.O. Box 3000 Lethbridge, Alberta, Canada T1J 4B1 Abstract. Canada’s grassland ecosystems have undergone major changes since the arrival of European agriculture, ranging from near-complete replacement of native biodiversity with annual crops to the effects of overgrazing by cattle on remnant native grasslands. The majority of the “agroecosystems” that have replaced the historical native grasslands now encompass completely new associations of plants and arthropods in what is typically a mix of introduced and native species. Some of these species are pests of crops and pastures and were accidentally introduced. Other species are natural enemies of these pests and were deliberately introduced as classical biological control (biocontrol) agents to control these pests. To control weeds, 76 arthropod species have been released against 24 target species in Canada since 1951, all of which also have been released in western Canada. Of these released species, 53 (70%) have become established, with 18 estimated to be reducing target weed populations. The biocontrol programs for leafy spurge in the prairie provinces and knapweeds in British Columbia have been the largest, each responsible for the establishment of 10 new arthropod species on rangelands. This chapter summarizes the ecological highlights of these programs and those for miscellaneous weeds. Compared with weed biocontrol on rangelands, classical biocontrol of arthropod crop pests by using arthropods lags far behind, mostly because of a preference to manage crop pests with chemicals. -

Biological Control Agents Elevate Hantavirus by Subsidizing Deer Mouse Populations

Ecology Letters, (2006) 9: 443–450 doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2006.00896.x LETTER Biological control agents elevate hantavirus by subsidizing deer mouse populations Abstract Dean E. Pearson* and Ragan M. Biological control of exotic invasive plants using exotic insects is practiced under the Callaway assumption that biological control agents are safe if they do not directly attack non-target Division of Biological Sciences, species. We tested this assumption by evaluating the potential for two host-specific University of Montana, biological control agents (Urophora spp.), widely established in North America for Missoula, MT 59812, USA spotted knapweed (Centaurea maculosa) control, to indirectly elevate Sin Nombre *Correspondence and present hantavirus by providing food subsidies to populations of deer mice (Peromyscus address: Dean E. Pearson, Rocky maniculatus), the primary reservoir for the virus. We show that seropositive deer mice Mountain Research Station, (mice testing positive for hantavirus) were over three times more abundant in the USDA Forest Service, 800 E. Beckwith Ave., Missoula, presence of the biocontrol food subsidy. Elevating densities of seropositive mice may MT 59801, USA. E-mail: increase risk of hantavirus infection in humans and significantly alter hantavirus ecology. [email protected] Host specificity alone does not ensure safe biological control. To minimize indirect risks to non-target species, biological control agents must suppress pest populations enough to reduce their own numbers. Keywords Biological control, Centaurea maculosa, disease ecology, food subsidies, hantavirus, indirect effects, invasive species, non-target effects, Peromyscus maniculatus, Urophora. Ecology Letters (2006) 9: 443–450 agents (Urophora spp.) widely established across western INTRODUCTION North America to control spotted knapweed (Centaurea Exotic plant invasions threaten the biological diversity of maculosa Lam.), indirectly increase the Sin Nombre natural ecosystems around the world (Wilcove et al. -

Some Observations on the Life-History and Bionomics of the Knapweed Gall- Fly Urophora Solstitialis Linn

142 SOME OBSERVATIONS ON THE LIFE-HISTORY AND BIONOMICS OF THE KNAPWEED GALL- FLY UROPHORA SOLSTITIALIS LINN. BY J. T. WADSWBRTH, Research Assistant, Department of Agricultural Entomology, University of Munchester. (With Plates XI and XI1 and 1 Text-figure.) CONTENTS. PAGE Introduction .......... 142 Description of fly and classification .......143 Geographical distribution .......... 145 Historical ............ 146 Food-plants . ........147 Life-history, dcsrript.ion of ovipositor, and method of oviposition . 148 Descriptions of ova, larvae, and pupae ......152 Effeet.s of larvae on production of seeds in galled flower-heads of Cextaurca nigra L. ........ 160 Pa,rssites ............ 163 Remarks on gall-formation, and on other inhabitant- of the flower- heads ............164 Summary ............ 165 Bibliography ..... ..... 166 Explanation of plates .........168 Introduction. INSeptember 1911;whilst collecting seeds of wild plants at Prestatyn, North Wales, I found galls in many of the flower-heads of the small knapweed, Centaurea nigra L., and these on further examination were found to contain dipterous larvae. On counting the seeds contained in a few of the galled flower-heads, and comparing the numbers obtained with the numbers present in ungalled heads, it was seen that considerably fewer seeds were present in the former than in the latter It therefore seemed probable that J . 'l'. WADSWORTH 143 the dipterous larvae present in the flomer-heads, by inducing gall- formation, caused a reduction in the number of the seeds normally produced by this troublesome and useless weed, which is very common in many pastures and meadows. A number of the infected heads were brought to Manchester, and kept until the following spring, when, towards the end of June, imagines commenced to emerge from the galls, and continued to do so during the ensuing three weeks. -

Diptera: Tephritidae) Released and Monitored by USDA, APHIS, PPQ As Biological Control Agents of Spotted and Diffuse Knapweed

The Great Lakes Entomologist Volume 30 Number 3 - Fall 1997 Number 3 - Fall 1997 Article 7 October 1997 Urophora Affinis and U. Quadrifasciata (Diptera: Tephritidae) Released and Monitored by USDA, APHIS, PPQ as Biological Control Agents of Spotted and Diffuse Knapweed R. F. Lang Montana State University R. D. Richard Montana State University R. W. Hansen Montana State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/tgle Part of the Entomology Commons Recommended Citation Lang, R. F.; Richard, R. D.; and Hansen, R. W. 1997. "Urophora Affinis and U. Quadrifasciata (Diptera: Tephritidae) Released and Monitored by USDA, APHIS, PPQ as Biological Control Agents of Spotted and Diffuse Knapweed," The Great Lakes Entomologist, vol 30 (2) Available at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/tgle/vol30/iss2/7 This Peer-Review Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Biology at ValpoScholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Great Lakes Entomologist by an authorized administrator of ValpoScholar. For more information, please contact a ValpoScholar staff member at [email protected]. Lang et al.: <i>Urophora Affinis</i> and <i>U. Quadrifasciata</i> (Diptera: Te 1997 THE GREAT LAKES ENTOMOLOGIST 105 UROPHORA AFFINIS AND U. QUADRIFASCIATA (DIPTERA: TEPHRITIDAE) RELEASED AND MONITORED BY USDA, APHIS, PPQ AS BIOLOGICAL CONTROL AGENTS OF SPOTIED AND DIFFUSE KNAPWEED R. F. lang,] R. D. Richard] and R. W. Hansen] ABSTRACT USDA, APHIS, PPQ has distributed the seedhead gall flies Urophora affinis and U. quadrifasciata (Diptera: Tephritidae) as classical biological agents of the introduced weeds spotted and diffuse knapweed (Centaurea maculosa and C. -

Biology and Biological Control of Yellow Starthistle

United States Department of Agriculture TECHNOLOGY TRANSFER Biological Control BIOLOGY AND BIOLOGICAL CONTROL OF YELLOW STARTHISTLE Carol Bell Randall, Rachel L. Winston, Cynthia A. Jette, Michael J. Pitcairn, and Joseph M. DiTomaso Forest Health Technology FHTET-2016-08 Enterprise Team 4th Ed., June 2017 The Forest Health Technology Enterprise Team (FHTET) was created in 1995 by the Deputy Chief for State and Private Forestry, USDA, Forest Service, to develop and deliver technologies to protect and improve the health of American forests. This book was published by FHTET as part of the technology transfer series. http://www.fs.fed.us/foresthealth/technology/ b e Cover Photos: (a) Yellow starthistle flower head (Peggy Grebb, USDA ARS, bugwood.org); (b) Bangasternus orientalis adult; (c) Eustenopus villosus adult; (d) Larinus curtus adult; (e) Chaetorellia spp. adult; (f) Urophora c f sirunaseva adult (b-f Laura Parsons & Mark Schwarzländer, University of Idaho); (g) Puccinia jaceae var. solstitialis (Stephen Ausmus, USDA ARS, bugwood.org) d a g References to pesticides appear in this publication. These statements do not constitute endorsement or recommendation of them by the U.S. Department of Agriculture, nor do they imply that the uses discussed have been registered. Use of most pesticides is regulated by state and federal laws. Applicable regulations must be obtained from the appropriate regulatory agency prior to their use. CAUTION: Pesticides can be injurious to humans, domestic animals, desirable plants, and fish or other wildlife if they are not handled or applied properly. Use all pesticides selectively and carefully. Follow recommended practices given on the label for the use and disposal of pesticides and pesticide containers. -

31762100155835.Pdf (5.721Mb)

A study of Urophora affinis (Diptera : Tephritidae) released on spotted knapweed in Western Montana by Jim Maynard Story A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE in Entomology Montana State University © Copyright by Jim Maynard Story (1976) Abstract: A gall-producing fly, Urophora affinis Frfld., was introduced into western Montana for the biological control of spotted knapweed (Centaurea maaulosa Lam.). Releases were made in 1973, 1974, and 1975 on spotted knapweed infestations. In 1973, 150 u. affinis were released into a field cage, while 279 u. affinis were field released. The u. affinis population within the field cage was found to have increased significantly over a two-year period, u: affinis galls were found at a distance of 50 m from the initial release point after two years; the adults were found throughout the field in very small numbers. A spider, Dietyna major Menge, was found preying on U. affinis adults; the impact of the spider on the U. affinis population was not determined. It is concluded that u. affinis successfully overwintered and became established at the primary study site in western Montana. The life history of V. affinis was found to be closely synchronized with the flower head development of its host plant, spotted knapweed. An increase in the number of v. affinis galls was found to decrease spotted knapweed seed production. Pronounced variation for morphological traits occurred among spotted knapweed plants. Phenology of spotted knapweed generally agreed with previous reports. STATEMENT OF PERMISSION TO COPY In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the require ments for an advanced degree at Montana State University, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for inspection.