The Assembly Hall Theatre, Sunday November 9Th 2008, 3.00Pm

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Local Area Guide

An insider’sguide to the local area Eating out A fantastic choice of places to eat and drink. p. 8 – 13 Great shopping Everyday essentials, designer fashion, to statement pieces for your new home. p. 14 – 17 Picturesque open spaces Amazingly beautiful Kent countryside, picturesque parks and historic gardens – yours to explore. p. 18 - 23 2 – 3 An insider’s guide From the delights of the English countryside right on your doorstep to connecting with friends over a coffee, Paddock Wood is well placed to A place to cater for all your needs. EX Foal Hurst Green is located in Paddock Wood, set in the heart of the Kent countryside, along a hedge-lined country road that winds through farmland, meadows and hop fields. Traditional oast houses dot the landscape and mature woodland that has stood for centuries provide shelter for wildlife. The far-reaching countryside views are simply stunning. For shopping, transport and entertainment, Paddock Wood and historic Royal Tunbridge Wells town centres are both close by. This guide gives an overview of the many advantages of living in Paddock Wood, and we hope you will find it useful. 4 – 5 Post Office Groceries Dentist PADDOCK WOOD POST OFFICE WAITROSE AYCLIFFE DENTISTRY 19-23 Commercial Road, Church Road, 49 Maidstone Road, Paddock Wood, TN12 6EN Paddock Wood, TN12 6EX Paddock Wood, TN12 6DG T 0345 611 2970 T 01892 836647 T 01892 833926 0.8 mile away 1.1 miles away 1.1 miles away Everyday Butchers Pharmacy Library POMFRET BROS PADDOCK WOOD PHARMACY PADDOCK WOOD LIBRARY 45 Commercial Road, 12 Commercial -

Ref.: TC/1136 30 March 2020 Hayley Starkey Tunbridge Wells Borough

Ref.: TC/1136 30 March 2020 Hayley Starkey Tunbridge Wells Borough Council Mount Pleasant Road Royal Tunbridge Wells Kent TN1 1RS By e-mail: [email protected] Application: 20/00752/FULL & 20/00753/LBC Site: Trinity Theatre And Arts Centre, Church Road, Royal Tunbridge Wells, Kent, TN1 1JP Proposal: Internal alterations to stairwells and clock tower for public access. New external up- lighting to the tower; and Listed Building Consent - Internal alterations to stairwells and clock tower for public access. New external up-lighting to the tower. Remit: The Theatres Trust is the national advisory public body for theatres. We were established through the Theatres Trust Act 1976 'to promote the better protection of theatres' and provide statutory planning advice on theatre buildings and theatre use in England through The Town and Country Planning (Development Management Procedure) (England) Order 2015, requiring the Trust to be consulted by local authorities on planning applications which include 'development involving any land on which there is a theatre'. Comment: This application for planning permission and listed building consent has come to the attention of the Trust as it results in development at the Grade II* listed Trinity Theatre. Trinity Theatre is a theatre and arts centre which has been operating within the former Holy Trinity Church since 1982. It is an important cultural and heritage asset for Tunbridge Wells and surrounding areas, supporting smaller to middle scale theatre and performing artists as well as local groups. It helps broaden access to culture and the arts for local people. Paragraph 92 of the NPPF (2019) seeks planning decisions to plan positively for facilities such as this. -

Your Local Area Guide to Royal Tunbridge Wells

YOUR LOCAL AREA GUIDE TO ROYAL TUNBRIDGE WELLS YOUR GUIDE TO ROYAL TUNBRIDGE WELLS Royal Tunbridge Wells is one of the most sought after towns in the South East of England. It has a relaxed yet sophisticated lifestyle, made more enjoyable by the elegant architecture and streets to be found all around you. The Kent countryside surrounds the town, offering even more attractions to enjoy. This guide gives an overview of the many advantages of living in Royal Tunbridge Wells, and we hope you will find it useful. AD O R S K D T R A Y A O A J W P R D O Y N T A R R H H W U O O 9 G N B O N R R D D U ’ S O E Y Y A V D N O R A E N R W S D L R A CL D N O O O O A SE R O C A R R U N E U D C G V L IO V Q B E L E R L U R N U E A D Grosvenor E C E P N D V P A P & Hilbert A A U N R O O K Park T D R OAD R S NG D ’ NI BY Culverden A A O S C O Park O E R R D M A N N A O E J R O LAKE I D T T M S A A T D C S A O 8 S R D 6 D A 2 Ashford ’S O L O A O R R D G A E A E L RO A YA O 7 and Dover D L R AD K B CH R IA RO A O A E VICTO R O YN SE 1 V 9 G E O AR N DEN P 10 A D MO A H RO RK D AD A 8 A 2 L O Y O N 1 R R EU AD 12 N O N X R P O E O A O N T R D 5 K IM S L A W B R A N R IS O R O O H AD H O A O R M D P 12 C P S ’S E T N N D N O A O U YO RK R L O D OAD W M 6 N R N ALVE LEY PA O C RK G P L AR 1 D A EN S R A264 K H ROAD 3 C CHURC A R L V 4 O E R 6 9 A L 2 E A D N Y W 2 RO O AD D ’S P O 6 SH BI D 8 A 1 O A264 R 4 DOWN T ’S K OP 3 Calverley C BISH C Tunbridge R E A Grounds A P Wellington S P S 4 Wells T 10 O 6 Rocks L Y E R Tunbridge Wells E 7 D L P A 16 Common R -

April 2014 May 2014 June 2014 July 2014

YOUR FREE GUIDE TO EVENTS IN (AND AROUND) TUNBRIDGE WELLS September 2021 1st South Pacific Hawkhurst Film 1st Andre Rieu: Together Again Trinity Theatre Classical Music 2nd NT Encore: Follies E M Forster Theatre / Tonbri... Theatre 2nd NT Live: Follies Hawkhurst Theatre 2nd NT Live: Follies Odeon Cinema: Special Events Theatre 2nd The Murder Capital The Forum Music 2nd Bumper Blyton Trinity Theatre Theatre 3rd Richard Hawley De La Warr Pavilion Music 3rd Pig Hawkhurst Film 3rd Stillwater Hawkhurst Film 3rd The Last Bus Hawkhurst Film 3rd The Nest Hawkhurst Film 3rd Annette Odeon Cinema: Films Film 3rd Rise Of The Footsoldier: Origins Odeon Cinema: Films Film 3rd Shang-Chi and the Legend of the Ten Rings Odeon Cinema: Films Film 3rd The New Orleans Echoes featuring Miss Penny Payne St Barnabas Church Music 4th The Kanneh-Masons Lamberhurst Classical Music 4th The Devout The Forum Music 4th Roy Orbison & the Traveling Wilburys Experience Trinity Theatre Music 5th Maximo Park: Nature Always Wins Album Release De La Warr Pavilion Music 5th The Handmaiden Hawkhurst Film 5th Sunday Funny Sunday: The Forum Comedy Night The Forum Comedy 5th NT Encore: Follies Trinity Theatre Theatre 6th Janine Jansen: Falling For Stradivari Hawkhurst Classical Music 6th Minari Trinity Theatre Film 7th Mick Fleetwood & Friends Celebrate Peter Green Odeon Cinema: Special Events Film 7th Flyte The Forum Music 7th Nomadland Trinity Theatre Film 8th The Wendy James Band The Forum Music 9th Lightning Seeds De La Warr Pavilion Music 9th Clare Teal and her Trio E M Forster Theatre / Tonbri... Music 9th Massive Wagons The Forum Music 10th Simon Amstell: Spirit Hole De La Warr Pavilion Comedy 10th Slapstick Picnic: The Importance of Being Earnest E M Forster Theatre / Tonbri.. -

July 2010 September 2010 October 2010

YOUR FREE GUIDE TO EVENTS IN (AND AROUND) TUNBRIDGE WELLS September 2021 1st South Pacific Hawkhurst Film 1st Andre Rieu: Together Again Trinity Theatre Classical Music 2nd NT Encore: Follies E M Forster Theatre / Tonbri... Theatre 2nd NT Live: Follies Hawkhurst Theatre 2nd NT Live: Follies Odeon Cinema: Special Events Theatre 2nd The Murder Capital The Forum Music 2nd Bumper Blyton Trinity Theatre Theatre 3rd Richard Hawley De La Warr Pavilion Music 3rd Pig Hawkhurst Film 3rd Stillwater Hawkhurst Film 3rd The Last Bus Hawkhurst Film 3rd The Nest Hawkhurst Film 3rd Annette Odeon Cinema: Films Film 3rd Rise Of The Footsoldier: Origins Odeon Cinema: Films Film 3rd Shang-Chi and the Legend of the Ten Rings Odeon Cinema: Films Film 3rd The New Orleans Echoes featuring Miss Penny Payne St Barnabas Church Music 4th The Kanneh-Masons Lamberhurst Classical Music 4th The Devout The Forum Music 4th Roy Orbison & the Traveling Wilburys Experience Trinity Theatre Music 5th Maximo Park: Nature Always Wins Album Release De La Warr Pavilion Music 5th The Handmaiden Hawkhurst Film 5th Sunday Funny Sunday: The Forum Comedy Night The Forum Comedy 5th NT Encore: Follies Trinity Theatre Theatre 6th Janine Jansen: Falling For Stradivari Hawkhurst Classical Music 6th Minari Trinity Theatre Film 7th Mick Fleetwood & Friends Celebrate Peter Green Odeon Cinema: Special Events Film 7th Flyte The Forum Music 7th Nomadland Trinity Theatre Film 8th The Wendy James Band The Forum Music 9th Lightning Seeds De La Warr Pavilion Music 9th Clare Teal and her Trio E M Forster Theatre / Tonbri... Music 9th Massive Wagons The Forum Music 10th Simon Amstell: Spirit Hole De La Warr Pavilion Comedy 10th Slapstick Picnic: The Importance of Being Earnest E M Forster Theatre / Tonbri.. -

Opportunity to Build an Individual Home in a Unique Setting on The

Opportunity to build an individual home in a unique setting on the edge of Royal Tunbridge Wells Planning Permission for a 5-bedroom house, of approximately 5380 sq ft, set within the Victorian walled garden of Blackhurst Park – all set in 1.4 acres The Walled Garden – Blackhurst Park – Halls Hole Road – Royal Tunbridge Wells – Kent TN2 4RG Location Blackhurst Park is situated on the eastern edge of the town, accessed from Halls Hole Road, just off the Pembury Road, with easy access to the A21(T). The centre of town is within 1½ miles with High Brooms rail station being approximately 1 mile distant, providing a frequent direct service to London Bridge in around 50 minutes. Description Blackhurst Park is a private residential estate, behind security gates, and is located on the south side of Pembury Road, at its junction with Halls Hole Road. The original Grade II listed house was converted around 20 years ago and provides 3 large attached “wings”, with mature landscaped gardens. The Walled Garden is now being offered for sale with the benefit of full planning permission to build a truly individual house, over two levels, by sculpting into the natural fall of the land. The completed house will provide 5 double bedrooms each with en-suite facilities, with the master bedroom also enjoying a dressing room. In all 5381 sq ft. On the ground floor there is large hall serving three bedrooms; two reception rooms; a kitchen / dining room; utility room; boot room. There are “wrap around” terraces overlooking the garden. – 2637 sq ft The garden level provides two further bedrooms; a gym; home office; changing / showroom; pool / plant / storerooms – leading directly out to a swimming pool and terrace area. -

CIVIC COMPLEX Consultation Report

Royal Tunbridge Wells CIVIC COMPLEX Consultation Report Produced on behalf of Tunbridge Wells Regeneration Company by M&N Communications Ltd Consultation Report | M&N Communications 3 Contents 1.0 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...............................................................................4 2.0 APPROACH TO CONSULTATION ..............................................................10 2.1 M&N’s brief ................................................................................................11 2.2 M&N’s approach to consultation ................................................................12 2.3 Tunbridge Wells Borough Council’s SCI and planning background .............13 3.0 STRATEGY, METHODOLOGY & PROGRAMME .......................................... 14 3.1 Strategy .....................................................................................................15 3.2 Methodology .............................................................................................17 3.3 Consultation programme ...........................................................................18 4.0 FEEDBACK ANALYSIS SUMMARY ............................................................33 4.1 Feedback analysis introduction ..................................................................34 4.2 Cultural uses – introduction ........................................................................34 4.3 Civic uses – introduction ............................................................................35 4.4 Public services - introduction .....................................................................37 -

September 2010 November 2010 December 2010

YOUR FREE GUIDE TO EVENTS IN (AND AROUND) TUNBRIDGE WELLS September 2021 1st South Pacific Hawkhurst Film 1st Andre Rieu: Together Again Trinity Theatre Classical Music 2nd NT Encore: Follies E M Forster Theatre / Tonbri... Theatre 2nd NT Live: Follies Hawkhurst Theatre 2nd NT Live: Follies Odeon Cinema: Special Events Theatre 2nd The Murder Capital The Forum Music 2nd Bumper Blyton Trinity Theatre Theatre 3rd Richard Hawley De La Warr Pavilion Music 3rd Pig Hawkhurst Film 3rd Stillwater Hawkhurst Film 3rd The Last Bus Hawkhurst Film 3rd The Nest Hawkhurst Film 3rd Annette Odeon Cinema: Films Film 3rd Rise Of The Footsoldier: Origins Odeon Cinema: Films Film 3rd Shang-Chi and the Legend of the Ten Rings Odeon Cinema: Films Film 3rd The New Orleans Echoes featuring Miss Penny Payne St Barnabas Church Music 4th The Kanneh-Masons Lamberhurst Classical Music 4th The Devout The Forum Music 4th Roy Orbison & the Traveling Wilburys Experience Trinity Theatre Music 5th Maximo Park: Nature Always Wins Album Release De La Warr Pavilion Music 5th The Handmaiden Hawkhurst Film 5th Sunday Funny Sunday: The Forum Comedy Night The Forum Comedy 5th NT Encore: Follies Trinity Theatre Theatre 6th Janine Jansen: Falling For Stradivari Hawkhurst Classical Music 6th Minari Trinity Theatre Film 7th Mick Fleetwood & Friends Celebrate Peter Green Odeon Cinema: Special Events Film 7th Flyte The Forum Music 7th Nomadland Trinity Theatre Film 8th The Wendy James Band The Forum Music 9th Lightning Seeds De La Warr Pavilion Music 9th Clare Teal and her Trio E M Forster Theatre / Tonbri... Music 9th Massive Wagons The Forum Music 10th Simon Amstell: Spirit Hole De La Warr Pavilion Comedy 10th Slapstick Picnic: The Importance of Being Earnest E M Forster Theatre / Tonbri.. -

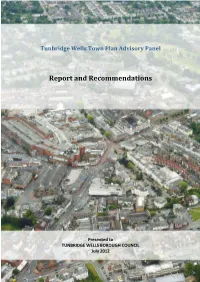

Report and Recommendations

1 Tunbridge Wells Town Plan Advisory Panel Report and Recommendations Presented to TUNBRIDGE WELLS BOROUGH COUNCIL July 2012 2 FOREWORD It is now around eight months since I set up the Tunbridge Wells Town Plan Panel with the purpose of better informing the debate on the future development of the town. Some finger crossing was needed at first since the exercise was new to all those involved, and required some pretty basic blue sky thinking. However, I am delighted that we are now able to publish our views, based on the consensus of the majority of the Panel members. Looking back, I feel privileged to have been part of a group of people who have shown such dedication and have given up so much of their time to the task. There will be those, no doubt, who will question the composition of the Panel and indeed its competence or mandate for doing this work. The choice of members was initially mine, and whilst I made every effort to ensure a balanced selection of skills and demographics, I was always aware that this could never be entirely perfect, and would be inevitably open to challenge. Despite this, however, I remain confident that the result is a valid and useful contribution to the consultation process. In particular, the thinking has been from the bottom up, starting with a clean sheet and few pre-conceived ideas. It is probable that the result may not be seen as dramatic, but I am convinced that it will prove to be of considerable significance in further informing the Borough Council's consultation on the Tunbridge Wells town centre plan. -

Cultural Strategy 2014-24 Index

Cultural Strategy 2014-24 Index Introduction 05 Vision 07 The Borough 09 The Challenges 11 The Plans – economy 17 The Plans – place 19 The Plans – people 21 Strategic Context 22 Photo credits 27 Introduction ‘Definitions of culture vary, but often they include Culture is an important component in broader museums, galleries, theatres, cinemas and borough council plans — the borough’s Draft libraries; music, dance, drama and comedy; Economic Strategy, Sustainable Communities visual arts, crafts and sculpture; digital, media Plan, and adopted and emerging Planning Policy and photography; books, poetry and writing; documents. This cultural strategy document architecture, design and the built environment; builds on those plans and outlines the high-level parks, gardens and the natural environment; retail, ambitions, cultural strengths & challenges, and the food and fashion – in fact many of the things that borough’s intentions to deliver these plans. can be found throughout the Borough of Tunbridge Wells. This strategy is necessarily pragmatic, with a focus on that which Tunbridge Wells Borough Council Culture is integral to everyday life. It contributes directly controls, and that which, in partnership, we to the economy, to a sense of place and enables believe we can deliver. people to work, learn, play and create together. It is one of the things that makes life better. We look forward to working closely with individuals, community groups, creative Over the last 12 months Tunbridge Wells Borough businesses and arts organisations so that together 04 Council has been listening to the community and we can make Tunbridge Wells a vibrant cultural 05 to the many who have been advocating for us to centre.’ develop an ambitious cultural strategy. -

Situation of Polling Stations

SITUATION OF POLLING STATIONS Election of the Police and Crime for the Kent Police Area Thursday 6 May 2021 Hours of Poll:- 7:00 am to 10:00 pm Notice is hereby given that: The situation of Polling Stations and the description of persons entitled to vote thereat are as follows: Ranges of Electoral Area electoral register Station Situation of Polling Station numbers of Number persons entitled to vote thereat Police Area St Matthew`s Church, High Brooms Road, A-1 to A- 1 County Division Tunbridge Wells 1592 Borough Ward Police Area St Matthew`s Church, High Brooms Road, A-1593 to A- 2 County Division Tunbridge Wells 3153 Borough Ward Police Area Southborough Community Centre, Crundwell B-1 to B- 3 County Division Road, Southborough, Tunbridge Wells 2359 Borough Ward Police Area St Thomas Church Hall, Pennington Road, C-1 to C- 4 County Division Southborough, Royal Tunbridge Wells 1669 Police Area St Thomas Church Hall, Pennington Road, C-1670 to C- 5 County Division Southborough, Royal Tunbridge Wells 3278 Police Area Bidborough Village Hall, Bidborough Ridge, County Division 6 D-1 to D-881 Bidborough, Tunbridge Wells Borough Ward Parish Area Police Area Langton Green Village Hall, Speldhurst Road, E-1 to E- 7 County Division Langton Green, Royal Tunbridge Wells 2633 Borough Ward Police Area Speldhurst Village Hall, St Marys Lane, F-1 to F- 8 County Division Speldhurst, Tunbridge Wells 1195 Borough Ward Police Area Brenchley Memorial Hall, Brenchley Road, G-1 to G- 9 County Division Brenchley, Tonbridge 1160 Borough Ward Police Area Matfield -

Host Brochure

HOLLYFIELDS 3 WELCOME TO HOLLYFIELDS Hollyfields is an elegant collection of 3, 4 and 5 bedroom homes nestled at the foot of the North Downs, just 1.5 miles from the historic and picturesque town centre of Royal Tunbridge Wells. Spacious, light-filled homes feature high specification kitchens and bathrooms, exquisite living and dining areas and private gardens. Ancient hedgerows allow wildlife to flourish, whilst play areas and wetlands open up plenty of outdoor fun and community activities. St. Peter’s* – an Ofsted ‘outstanding’ school is relocating to Hollyfields, a new primary school sympathetically designed into the development. London Bridge and Charing Cross are accessible by rail in as little as 42 minutes** at peak times. Close links to the motorway network and Eurostar put national and international destinations within easy reach. Overlooking beautiful countryside, Hollyfields truly combines a charming rural village with contemporary, connected living. *Planning consent has been granted for a school and will be built by Kent County Council **Source: trainline.com Computer generated image of Hollyfields. Indicative only. 4 HOLLYFIELDS HAWKENBURY, ROYAL TUNBRIDGE WELLS 5 TUNBRIDGE WELLS TUNBRIDGE WELLS HAWKENBURY ALL HAWKENBURY THE PANTILES GOLF CLUB RAILWAY STATION WEATHER FOOTBALL PITCH RECREATION GROUND A UNIQUE HAWKENBURY CAMDEN LOCATION VILLAGE PARK ROYAL TUNBRIDGE WELLS Hollyfields lies in Hawkenbury, just a few minutes’ drive from Royal Tunbridge Wells or a 30 minute walk. The village offers sports and leisure facilities, an Inn, a convenience store and a popular butchers. It’s the perfect base for heading out to explore Kent’s glorious countryside, ancient castles and famous gardens.