Caspar David Friedrich, Ancient Rome and the Freiheitskrieg

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Network Map of Knowledge And

Humphry Davy George Grosz Patrick Galvin August Wilhelm von Hofmann Mervyn Gotsman Peter Blake Willa Cather Norman Vincent Peale Hans Holbein the Elder David Bomberg Hans Lewy Mark Ryden Juan Gris Ian Stevenson Charles Coleman (English painter) Mauritz de Haas David Drake Donald E. Westlake John Morton Blum Yehuda Amichai Stephen Smale Bernd and Hilla Becher Vitsentzos Kornaros Maxfield Parrish L. Sprague de Camp Derek Jarman Baron Carl von Rokitansky John LaFarge Richard Francis Burton Jamie Hewlett George Sterling Sergei Winogradsky Federico Halbherr Jean-Léon Gérôme William M. Bass Roy Lichtenstein Jacob Isaakszoon van Ruisdael Tony Cliff Julia Margaret Cameron Arnold Sommerfeld Adrian Willaert Olga Arsenievna Oleinik LeMoine Fitzgerald Christian Krohg Wilfred Thesiger Jean-Joseph Benjamin-Constant Eva Hesse `Abd Allah ibn `Abbas Him Mark Lai Clark Ashton Smith Clint Eastwood Therkel Mathiassen Bettie Page Frank DuMond Peter Whittle Salvador Espriu Gaetano Fichera William Cubley Jean Tinguely Amado Nervo Sarat Chandra Chattopadhyay Ferdinand Hodler Françoise Sagan Dave Meltzer Anton Julius Carlson Bela Cikoš Sesija John Cleese Kan Nyunt Charlotte Lamb Benjamin Silliman Howard Hendricks Jim Russell (cartoonist) Kate Chopin Gary Becker Harvey Kurtzman Michel Tapié John C. Maxwell Stan Pitt Henry Lawson Gustave Boulanger Wayne Shorter Irshad Kamil Joseph Greenberg Dungeons & Dragons Serbian epic poetry Adrian Ludwig Richter Eliseu Visconti Albert Maignan Syed Nazeer Husain Hakushu Kitahara Lim Cheng Hoe David Brin Bernard Ogilvie Dodge Star Wars Karel Capek Hudson River School Alfred Hitchcock Vladimir Colin Robert Kroetsch Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai Stephen Sondheim Robert Ludlum Frank Frazetta Walter Tevis Sax Rohmer Rafael Sabatini Ralph Nader Manon Gropius Aristide Maillol Ed Roth Jonathan Dordick Abdur Razzaq (Professor) John W. -

Aarbøger for Nordisk Oldkyndighed Og Historie

aarbøger for nordisk Oldkyndighed og Historie Annual of the Royal Society of Northern Antiquaries 2007 Det Kongelige Nordiske Oldskriftselskab København 2010 65227_aarbog2007_.indd 3 09-03-2010 15:57:26 © 2010 Det Kgl. Nordiske Oldskriftselskab Frederiksholms Kanal 12 DK-1220 København K. ISBN 978-87-87483-14-8 ISSN 0084-585X Redaktion: Poul Otto Nielsen (ansv.) og Ulla Lund Hansen Grafisk tilrettelæggelse og billedbehandling: Jan Holme Andersen Udgivet med støtte fra Forskningsrådet for Kultur og Kommunikation Grunddesign, prepress og tryk: Narayana Press, Gylling Skrift: Minion Papir: 130 g Chorus Satin Omslag: Den Kongelige Commission for Oldsagers Opbevaring nedsat ved forordning af Kong Christian VII den 22. maj 1807 Medlemmer i perioden 1807-1816, fra toppen mod højre: Kommissionens formand A.W. Hauch, F. Münter, kommissionens sekretær R. Nyerup, P.J. Monrad, W.H.F. Abrahamson, B. Thorlacius, E. Vargas Bedemar, E.C. Werlauff, og L.S. Vedel Simonsen Alle manuskripter sendes til vurdering hos to anonyme referees, inden de accepteres til trykning All papers are subject to anonymous peer refereeing Vor einer möglichen Publikation werden alle Manuskripte zwei anonymen Referenten zur Begutachtung vorgelegt Salg til ikke-medlemmer i kommission hos: Herm. H. J. Lynge & Søn Internationalt antikvariat Silkegade 11 DK-1113 København K. www.lynge.com [email protected] Salg med rabat til medlemmer direkte fra Selskabet – se bagest i bogen 65227_aarbog2007_.indd 4 09-03-2010 15:57:26 Oldsagskommissionens tidlige år forudsætninger og internationale forbindelser Nationalmuseets 200 års Jubilæumssymposium 24.-25. maj 2007 arrangeret af Nationalmuseet og Wormianum i samarbejde med Kulturarvsstyrelsen 65227_aarbog2007_.indd 5 09-03-2010 15:57:26 Kong Hildetands høj. -

The Concept of Bildung in Early German Romanticism

CHAPTER 6 The Concept of Bildung in Early German Romanticism 1. Social and Political Context In 1799 Friedrich Schlegel, the ringleader of the early romantic circle, stated, with uncommon and uncharacteristic clarity, his view of the summum bonum, the supreme value in life: “The highest good, and [the source of] ev- erything that is useful, is culture (Bildung).”1 Since the German word Bildung is virtually synonymous with education, Schlegel might as well have said that the highest good is education. That aphorism, and others like it, leave no doubt about the importance of education for the early German romantics. It is no exaggeration to say that Bildung, the education of humanity, was the central goal, the highest aspiration, of the early romantics. All the leading figures of that charmed circle—Friedrich and August Wilhelm Schlegel, W. D. Wackenroder, Friedrich von Hardenberg (Novalis), F. W. J. Schelling, Ludwig Tieck, and F. D. Schleiermacher—saw in education their hope for the redemption of humanity. The aim of their common journal, the Athenäum, was to unite all their efforts for the sake of one single overriding goal: Bildung.2 The importance, and indeed urgency, of Bildung in the early romantic agenda is comprehensible only in its social and political context. The young romantics were writing in the 1790s, the decade of the cataclysmic changes wrought by the Revolution in France. Like so many of their generation, the romantics were initially very enthusiastic about the Revolution. Tieck, Novalis, Schleiermacher, Schelling, Hölderlin, and Friedrich Schlegel cele- brated the storming of the Bastille as the dawn of a new age. -

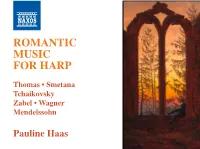

Romantic Music for Harp

ROMANTIC MUSIC FOR HARP Thomas • Smetana Tchaikovsky Zabel • Wagner Mendelssohn Pauline Haas 1 The Vision of a Dreamer by Pauline Haas A troubling landscape, the remains of an abbey, or maybe of a castle – the horizon in the distance stands out against the dusk. In the middle of the ruins, in the frame of an unglazed window, a young man is seated in profile. Is he dreaming? Is he doubting? Is he believing? The Dreamer is a journey of initiation: it is about Man travelling down his path of life pursued by his double, it is about an artist in pursuit of truth. I have contemplated this painting, seeing in it my own image as though in a mirror. I have created the image of this individual as a picture of my own dreams. I was his age when I made this recording – the age when one leaves childhood behind to enter the wider world and face up to oneself. I became conscious that the instrument lying against my shoulder, which had inspired so many poets and artists, but had been abandoned by musicians was, in my hands, like a blank page. I placed on my music stand, therefore, the traditional repertoire for the harp, other works considered inaccessible for the harpist, works which had long maintained a magical impact on me. I have woven a connecting thread between these works, nuancing the virgin whiteness of my page without managing to reach all the possible heights. Like a figure in a painting by Caspar David Friedrich this programme contemplates a distant horizon. -

The Landscape of Longing

Caspar David Friedrich^ the peculiar Romantic. The Landscape of Longing BY ANNE HOLLANDER nly nine oil paintings and exhibition de\oted t(.> Friedricb ever to ticeable thing abotit this mini-retro- eleven works on paper be moimted in tbis coiuitiy. It is possible spective is its consistency. Friedrich iiKikc lip the Metropolitan that many more Friedricbs still lurk in perfected his method by 1808 and O Mtiseiiin's current exhibi- the Soviet Union, unknown in tbe West, never changed it, even dining the peri- tion of Caspar David Fricdricli's works even in repiodnction; but for now we are od after his stroke in 1835, wben he from Russia; and thev are only mininiallv gi'eatly pleased to see these. worked very little. augmeiilfd by a lew engravings, owned They are few, and many are ver\' Friedricb never dated bis paintings, by ibe niiist'uin. wliicb were made by ibe small, aitbotigb two of tbem, meastir- and lie sbowed none of tbat obsession artist's brotber from some with development so com- of Friedricb's 180:i draw- mon to artists of his peri- ings. Housed far to the od and to others ever rear of tbe main floor in a since. Apparently lie bad small section ol tbe I.eb- no need to enact a \isible man wing, this sbow must figbt for artistic teriitorA, be sotiglit otit, but it is im- to be seen to be struggling portant despite its small steadily along insicle the si/e and ascetic Haxor. C.as- meditmi itself, to give per- par David Friedricb (I 774- pettial evidence of bis per- 1H40) is now generally ac- sonal battle witb tbe in- knowledged as a great tractable eye, tbe pesky Romantic painter, and materials, tbe superior predecessors, (he pre.sent space lias been made for ri\als, with aljiding artistic bim beside I inner, (ieri- problems and new selt- cault, Blake, and Goya on imposed technical tasks, tbe roster of Eaily Nine- vvitli dominant opinion, teenth Centnry Originals. -

Joseph Beuys and the Reincarnation of German Romanticism

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Supervised Undergraduate Student Research Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects and Creative Work Spring 5-2003 Postwar Landscapes: Joseph Beuys and the Reincarnation of German Romanticism Lauren Elizabeth Smith University of Tennessee - Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_chanhonoproj Recommended Citation Smith, Lauren Elizabeth, "Postwar Landscapes: Joseph Beuys and the Reincarnation of German Romanticism" (2003). Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_chanhonoproj/601 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Supervised Undergraduate Student Research and Creative Work at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ----------------~~------~--------------------- Postwar Landscapes: Joseph Beuys and the Reincarnation of German Romanticism Lauren E. Smith College Scholars Senior Thesis University of Tennessee May 1,2003 Dr. Dorothy Habel, Dr. Tim Hiles, and Dr. Peter Hoyng, presiding committee Contents I. Introduction 3 II. Beuys' Germany: The 'Inability to Mourn' 3 III. Showman, Shaman, or Postwar Savoir? 5 IV. Beuys and Romanticism: Similia similibus curantur 9 V. Romanticism in Action: Celtic (Kinloch Rannoch) 12 VI. Celtic+ ---: Germany's symbolic salvation in Basel 22 VII. Conclusion 27 Notes Bibliography Figures Germany, 1952 o Germany, you're torn asunder And not just from within! Abandoned in cold and darkness The one leaves the other alone. And you've got such lovely valleys And plenty of thriving towns; If only you'd trust yourself now, Then all would be just fine. -

GERMAN LITERARY FAIRY TALES, 1795-1848 by CLAUDIA MAREIKE

ROMANTICISM, ORIENTALISM, AND NATIONAL IDENTITY: GERMAN LITERARY FAIRY TALES, 1795-1848 By CLAUDIA MAREIKE KATRIN SCHWABE A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2012 1 © 2012 Claudia Mareike Katrin Schwabe 2 To my beloved parents Dr. Roman and Cornelia Schwabe 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First and foremost, I would like to thank my supervisory committee chair, Dr. Barbara Mennel, who supported this project with great encouragement, enthusiasm, guidance, solidarity, and outstanding academic scholarship. I am particularly grateful for her dedication and tireless efforts in editing my chapters during the various phases of this dissertation. I could not have asked for a better, more genuine mentor. I also want to express my gratitude to the other committee members, Dr. Will Hasty, Dr. Franz Futterknecht, and Dr. John Cech, for their thoughtful comments and suggestions, invaluable feedback, and for offering me new perspectives. Furthermore, I would like to acknowledge the abundant support and inspiration of my friends and colleagues Anna Rutz, Tim Fangmeyer, and Dr. Keith Bullivant. My heartfelt gratitude goes to my family, particularly my parents, Dr. Roman and Cornelia Schwabe, as well as to my brother Marius and his wife Marina Schwabe. Many thanks also to my dear friends for all their love and their emotional support throughout the years: Silke Noll, Alice Mantey, Lea Hüllen, and Tina Dolge. In addition, Paul and Deborah Watford deserve special mentioning who so graciously and welcomingly invited me into their home and family. Final thanks go to Stephen Geist and his parents who believed in me from the very start. -

Professor Dr. Michelle Facos

Professor Dr. Michelle Facos Alfried Krupp Junior Fellow Oktober 2010 – September 2011 The Copenhagen Academy and artistic (Gedanken über die Nachahmung der grie- Kurzbericht innovation circa 1800 chischen Werke in Malerei und Bildhauer- kunst, 1755) conceptually rather than lite- In the late eighteenth and early nineteenth rally, and centuries several painters and sculptors who studied at the Copenhagen Academy of Art 3) the political mandate to create a distinct- (Det Kongelige Danske Kunstakademi) pro- ly Danish school of art. The works of pain- duce inventive art works that transgressed ters Nicolai Abildgaard, Jens Juel, Christof- contemporary norms and anticipated broader fer Eckersberg, and Caspar David Friedrich, artistic trends by decades. This was due in lar- and the sculptor and Winckelmann protégé Kurzvita Michelle Facos was born in Buffalo 1955. (California, 2008) and An Introduction to ge part to the singular confluence of several Johannes Wiedewelt evidence the indepen- She is professor of the History of Art and Nineteenth-Century Art (Routledge 2011). factors: dent creativity that would later become the adjunct professor of Jewish Studies at Indi- Michelle Facos has received awards from 1) a visual practice that emphasized careful- hallmark of modern artistic practice and ana University, Bloomington, where she has the American-Scandinavian Foundation, the ly observing and recording the natural world which are often attributed to French artists. taught since 1995. She received her Ph.D. in American Philosophical Society, Fulbright, (partly the result of the Institute for Natural 1989 from the Institute of Fine Arts, New and the Alexander von Humboldt-Stiftung. History being housed in the same building, York University with a dissertation entitled Charlottenborg Palace, as the Art Academy), Nationalism and the Nordic Imagination: Swedish Art of the 1890s. -

Some Recent Definitions of German Romanticism, Or the Case Against Dialectics

SOME RECENT DEFINITIONS OF GERMAN ROMANTICISM, OR THE CASE AGAINST DIALECTICS by Robert L. Kahn When the time came for me to be seriously thinking about writing this paper-and you can see from the title and description that I gave myself plenty of leeway-I was caught in a dilemma. In the beginning my plan had been simple enough: I wanted to present a report on the latest develop- ments in the scholarship of German Romanticism. As it turned out, I had believed very rashly and naively that I could carry on where Julius Peter- sen's eclectic and tolerant book Die Wesensbestimmung der deutschen Romantik (Leipzig, 1926), Josef Komer's fragmentary and unsystematic reviews in the Marginalien (Frankfurt a. M., 1950), and Franz Schultz's questioning, though irresolute, paper "Der gegenwartige Stand der Roman- tikforschungM1had left off. As a matter of fact, I wrote such an article, culminating in what I then considered to be a novel definition of German Romanticism. But the more I thought about the problem, the less I liked what I had done. It slowly dawned on me that I had been proceeding on a false course of inquiry, and eventually I was forced to reconsider several long-cherished views and to get rid of certain basic assumptions which I had come to recognize as illusory and prejudicial. It became increasingly obvious to me that as a conscientious literary historian I could not discuss new contributions to Romantic scholarship in vacuo, but that I was under an obligation to relate the spirit of these pronouncements to our own times, as much as to relate their substance to the period in question. -

Danmarks Kunstbibliotek the Danish National Art Library

Digitaliseret af / Digitised by Danmarks Kunstbibliotek The Danish National Art Library København / Copenhagen For oplysninger om ophavsret og brugerrettigheder, se venligst www.kunstbib.dk For information on copyright and user rights, please consult www.kunstbib.dk . o. (ORPORATfON OF Londoi 7IRTG7ILLE1? IgpLO G U i OF THE LOAN COLLECTIO o f Picture 1907 PfeiCE Sixpence <Art Gallery of the (Corporation o f London. w C a t a l o g u e of the Exhibition of Works by Danish Painters. BY A. G. TEMPLE, F.S.A., Director of the 'Art Gallery of the Corporation of London. THOMAS HENRY ELLIS, E sq., D eputy , Chairman. 1907. 3ntrobuction By A. G. T e m p l e , F.S.A, H E earliest pictures in the present collection are T those of C arl' Gustav Pilo, and Jens Juel. Painted at a time in the 1 8 th century when the prevalent and popular manner was that better known to us by the works o f the notable Frenchmen, Largillibre, Nattier, De Troy and others, these two painters caught something o f the naivété and grace which marked the productions of these men. In so clear a degree is this observed, not so much in genre, as in portraiture, that the presumption is, although it is not on record, at any rate as regards Pilo, that they must both have studied at some time in the French capital. N o other painters of note, indigenous to the soil o f Denmark, had allowed their sense of grace such freedom to so express itself. -

An Eye for Landscapes That Transcend Nature,” the New York Times, May 22, 2009

Genocchio, Benjamin. “An Eye for Landscapes That Transcend Nature,” The New York Times, May 22, 2009. An Eye for Landscapes That Transcend Nature One’s lasting impression of the April Gornik exhibition at the Heckscher Museum of Art in Huntington is the sheer virtuosity of the pictures. They glow with mystery and grandeur. Landscape painting of this quality is not often seen on Long Island. Assembled by Kenneth Wayne, the museum’s chief curator, the show focuses on the artist’s powerful, large-scale oil paintings. There are a dozen pictures, created roughly from the late 1980s to the present, nicely displayed in two of the Heckscher’s newly renovated galleries. The removal of a false ceiling in them has allowed the museum to accommodate much larger works than it could before. New Horizons. The large-scale oil paintings by April Gornik on display at the Heckscher include “Sun Storm Sea” (2005). At 56, Ms. Gornik is already a painter of eminence. She has had shows around the world, and her work is in several major museum collections, including those of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Museum of Modern Art and the Whitney Museum of American Art. I would place her among the top landscape artists working in America today. That this is Ms. Gornik’s first major solo exhibition on Long Island in more than 15 years seems an oversight, especially given that she lives part of the year in Suffolk County. But better late than never, for there are probably dozens of artists living and working on Long Island who are deserving of shows. -

Danmarks Kunstbibliotek the Danish National Art Library

Digitaliseret af / Digitised by Danmarks Kunstbibliotek The Danish National Art Library København / Copenhagen For oplysninger om ophavsret og brugerrettigheder, se venligst www.kunstbib.dk For information on copyright and user rights, please consult www.kunstbib.dk IH. FÁAB0R6 KOBBERSTIKKEREN I F, CLEMENS D49-Í8SÍ i/VVWVWWVVV I C I 9 3 -H r.. V - . ■ j,, > .....j v ^i^ O g a S T , \1,?.. ‘s, - ' .,•-'i*', v^ S B l- - . » a ¡ t i * . ..' ■’.. ■ H M KOBBERSTIKKEREN F. CLEMENS 1749— 1831 '/' rj/ ~ ' I KOBBERSTIKKEREN J. F. CLEMENS 1749—1831 LIDT OM HANS LIV OG HANS VIRKSOMHED AF TH. FAABORG H.HVENEGAARD (WINKEL & MAGNUSSENS KUNSTFORLAG) KØBENHAVN 1918 i Nr. 238. J. F. C lemens KUNSTAK DEMIETS BISL OTHEK. OHAN FREDERIK CLEMENS havde i Sammenligning med den ligeledes tysk fødte P reisler — Sammenligningen ligger J nær — det Fortrin, at han kom til Danmark som ganske lille Dreng. Om Samtiden lagde Mærke til eller nogen Vægt paa den Forskel, som derved opstod i de to Kobberstikkeres Kunst, er tvivlsomt. Det var i hvert Fald ganske ubevidst. Men vor Tid glæder sig over Clemens’ troskyldige, godlidende og enkle Danskhed, som han med sin stilfærdige og beskedne Natur havde let ved at tilegne sig, og som ogsaa prægede de fleste, navnlig de bedste af hans Arbejder. Medens den halv andet Hundrede Aar ældre H a e l w e g h , der ikke alene var født i Danmark, men sikkert ogsaa det fremmedklingende Navn til Trods, havde en god dansk Herkomst, selvfølgelig ikke for- CITYTRYKKERIET • VALDEMAR CARLSEN • KØBENHAVN • maaede at lade noget nationalt ejendommeligt komme frem — 3 — i sine efter udprægede Nederlændere som van M and er og alene en Snes Portrætter, der ikke findes anført hos Fick, me W uc h ter stukne Blade, og medens Preisler i sin europæisk dens denne nævner nogle mindre vigtige, som savnes paa Ud virkende Elegance og maleriske Verve fremtræder som en stillingen.