German Ocean Shipping and the Port of Antwerp, 1875-1914 an Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Coordination Failure and the Sinking of Titanic

The Sinking of the Unsinkable Titanic: Mental Inertia and Coordination Failures Fu-Lai Tony Yu Department of Economics and Finance Hong Kong Shue Yan University Abstract This study investigates the sinking of the Titanic from the theory of human agency derived from Austrian economics, interpretation sociology and organizational theories. Unlike most arguments in organizational and management sciences, this study offers a subjectivist perspective of mental inertia to understand the Titanic disaster. Specifically, this study will argue that the fall of the Titanic was mainly due to a series of coordination and judgment failures that occurred simultaneously. Such systematic failures were manifested in the misinterpretations of the incoming events, as a result of mental inertia, by all parties concerned in the fatal accident, including lookouts, telegram officers, the Captain, lifeboat crewmen, architects, engineers, senior management people and owners of the ship. This study concludes that no matter how successful the past is, we should not take experience for granted entirely. Given the uncertain future, high alertness to potential dangers and crises will allow us to avoid iceberg mines in the sea and arrived onshore safely. Keywords: The R.M.S. Titanic; Maritime disaster; Coordination failure; Mental inertia; Judgmental error; Austrian and organizational economics 1. The Titanic Disaster So this is the ship they say is unsinkable. It is unsinkable. God himself could not sink this ship. From Butler (1998: 39) [The] Titanic… will stand as a monument and warning to human presumption. The Bishop of Winchester, Southampton, 1912 Although the sinking of the Royal Mail Steamer Titanic (thereafter as the Titanic) is not the largest loss of life in maritime history1, it is the most famous one2. -

The Role of Transatlantic Shipping Companies in Euro-American Relations

Ports as tools of european expansion The Role of Transatlantic Shipping Companies in Euro-American Relations Antoine RESCHE ABSTRACT Between the arrival of transatlantic steamships in the 1830s and the popularization of air transport in the 1950s, shipping companies provided the only means of crossing the Atlantic, for both people as well as goods and mail. Often linked to governments by agreements, notably postal ones, they also had the important mission of representing national prestige, particularly in the United Kingdom, but also in France, Germany, and the United States. Their study thus makes it possible to determine what the promising migratory flows were during different periods, and how they were shared between the different companies. Ownership of these companies also became an issue that transcended borders, as in the case of the trust belonging to the financier John Pierpont Morgan, the International Mercantile Marine Company, which included British and American companies. A major concern from the viewpoint of states, their most prestigious ships became veritable ambassadors tasked with exporting the know-how and culture of their part of the world. Advertising poster for the Norddeutscher Lloyd company, around 1903. Source : Wikipédia Immigrant children in Ellis Island. Photograph by Brown Brothers, around 1908. Records of the Public Health Service, (90-G-125-29). Source : National Archives and Records Administration. Transatlantic Shipping Companies, Essential Actors in Euro-American Relations? Beginning with the first crossing in 1838 made exclusively with steam power, transatlantic lines were the centre of attention: until the coming of the airplane as a means of mass transportation in the 1950s, the sea was the only way to go from Europe to the United States. -

S/S Nevada, Guion Line

Page 1 of 2 Emigrant Ship databases Main Page >> Emigrant Ships S/S Nevada, Guion Line Search for ships by name or by first letter, browse by owner or builder Shipowner or Quick links Ships: Burden Built Dimensions A - B - C - D - E - F - G - H - I - J - K - L - operator M - N - O - P - Q - R - S - T - U - V - W - X - 3,121 1868 at Jarrow-on-Tyne by Palmer's 345.6ft x Y - Z - Æ - Ø - Å Guion Line Quick links Lines: gross Shipbuilding & Iron Co. Ltd. 43.4ft Allan Line - American Line - Anchor Line - Beaver Line - Canadian Pacific Line - Cunard Line - Dominion Line - Year Departure Arrival Remarks Guion Line - Hamburg America Line - Holland America Line - Inman Line - 1868 Oct. 17, launched Kroneline - Monarch Line - 1869 Feb. 2, maiden voyage Liverpool Norwegian America Line - National Line - Norddeutscher Lloyd - Red Star Line - - Queenstown - New York Ruger's American Line - Scandia Line - 1870 Liverpool New York Aug. 13 Liverpool & Great Wester Steam Scandinavian America Line - State Line - Swedish America Line - Temperley Line Ship Company - Norwegian American S.S. Co. - 1870 Liverpool New York Sept. 25 Liverpool & Great Wester Steam Thingvalla Line - White Star Line - Wilson Line Ship Company 1870 Liverpool New York Nov. 06 Liverpool & Great Wester Steam Agents & Shipping lines Ship Company Shipping lines, Norwegian agents, authorizations, routes and fleets. 1871 Liverpool New York Aug. 07 Agent DHrr. Blichfeldt & Co., Christiania Emigrant ship Arrivals 1871 Liverpool New York Sept. 17 Trond Austheim's database of emigrant ship arrivals around the world, 1870-1894. 1871 Liverpool New York Oct. -

Editorials Eugene Vidal

Journal of Air Law and Commerce Volume 6 | Issue 4 Article 17 1935 Editorials Eugene Vidal Martin Wronsky Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.smu.edu/jalc Recommended Citation Eugene Vidal et al., Editorials, 6 J. Air L. & Com. 578 (1935) https://scholar.smu.edu/jalc/vol6/iss4/17 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at SMU Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Air Law and Commerce by an authorized administrator of SMU Scholar. For more information, please visit http://digitalrepository.smu.edu. EDITORIALS AERONAUTICAL DEVELOPMENTS* From time to time there has been public criticism of the manner in which this Administration is dealing with civil aero- nautics, and particularly of the Administration's treatment of the scheduled air lines. Herewith are some facts and figures of an impartial nature prepared by the Bureau of Air Commerce, De- partment of Commerce, which show the progress of the industry (luring the past two years. The scheduled operators are now in the midst of a campaign of record breaking. In the first six months of 1935 the scheduled air lines (domestic and foreign extensions) flew 28,729,128 miles, carried 377,339 passengers on air journeys totaling 162,858,746 passenger miles, and transported 2,221,013 pounds of express. The passenger, passenger miles, which are after all a measure of rev- enue, and express totals were new records. The total number of passengers carried in six months, from January to June of this year, was more than double the number for the entire year 1929, and 60 per cent above 1933, the year prior to the air mail cancella- tions. -

Bibliography

Bibliography AIR FRANCE Carlier, c., ed. 'La construction aeronautique, Ie transport aenen, a I'aube du XXIeme siecle'. Centre d'Histoire de l'Industrie Aeronautique et Spatiale, Uni versity of Paris I, 1989. Chadeau, E., ed. 'Histoire de I'aviation civile'. Vincennes, Comite Latecoere and Service Historique de l'Annee de l'Air, 1994. Chadeau, E., ed. 'Airbus, un succes industriel europeen'. Paris, Institut d'Histoire de l'Industrie, 1995. Chadeau, E. 'Le reve et la puissance, I'avion et son siecle'. Paris, Fayard, 1996. Dacharry, M. 'Geographie du transport aerien'. Paris, LITEC, 1981. Esperou, R. 'Histoire d'Air France'. La Guerche, Editions Ouest France, 1986. Funel, P., ed. 'Le transport aerien fran~ais'. Paris, Documentation fran~aise, 1982. Guarino, J-G. 'La politique economique des entreprises de transport aerien, Ie cas Air France, environnement et choix'. Doctoral thesis, Nice University, 1977. Hamelin, P., ed. 'Transports 1993, professions en devenir, enjeux et dereglementation'. Paris, Ecole nationale des Ponts et Chaussees, 1992. Le Due, M., ed. 'Services publics de reseau et Europe'. Paris, Documentation fran ~ise, 1995. Maoui, G., Neiertz, N., ed. 'Entre ciel et terre', History of Paris Airports. Paris, Le Cherche Midi, 1995. Marais, J-G. and Simi, R 'Caviation commerciale'. Paris, Presses universitaires de France, 1964. Merlin, P. 'Geographie, economie et planification des transports'. Paris, Presses uni- versitaires de France, 1991. Merlin, P. 'Les transports en France'. Paris, Documentation fran~aise, 1994. Naveau, J. 'CEurope et Ie transport aerien'. Brussels, Bruylant, 1983. Neiertz, N. 'La coordination des transports en France de 1918 a nos jours'. Unpub lished doctoral thesis, Paris IV- Sorbonne University, 1995. -

Shipping Made in Hamburg

Shipping made in Hamburg The history of the Hapag-Lloyd AG THE HISTORY OF THE HAPAG-LLOYD AG Historical Context By the middle of the 19th Century the industrial revolution has caused the disap- pearance of many crafts in Europe, fewer and fewer workers are now required. In a first process of globalization transport links are developing at great speed. For the first time, railways are enabling even ordinary citizens to move their place of residen- ce, while the first steamships are being tested in overseas trades. A great wave of emigration to the United States is just starting. “Speak up! Why are you moving away?” asks the poet Ferdinand Freiligrath in the ballad “The emigrants” that became something of a hymn for a German national mo- vement. The answer is simple: Because they can no longer stand life at home. Until 1918, stress and political repression cause millions of Europeans, among them many Germans, especially, to make off for the New World to look for new opportunities, a new life. Germany is splintered into backward princedoms under absolute rule. Mass poverty prevails and the lower orders are emigrating in swarms. That suits the rulers only too well, since a ticket to America produces a solution to all social problems. Any troublemaker can be sent across the big pond. The residents of entire almshouses are collectively despatched on voyage. New York is soon complaining about hordes of German beggars. The dangers of emigration are just as unlimited as the hoped-for opportunities in the USA. Most of the emigrants are literally without any experience, have never left their place of birth, and before the paradise they dream of, comes a hell. -

Die Deutschen Schnelldampfer. T. V, "Bremen" Und "Europa" - Ausklang Einer Ära Kludas, Arnold

www.ssoar.info Die deutschen Schnelldampfer. T. V, "Bremen" und "Europa" - Ausklang einer Ära Kludas, Arnold Veröffentlichungsversion / Published Version Zeitschriftenartikel / journal article Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Kludas, A. (1988). Die deutschen Schnelldampfer. T. V, "Bremen" und "Europa" - Ausklang einer Ära. Deutsches Schiffahrtsarchiv, 11, 1-177. https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-55875-1 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer Deposit-Lizenz (Keine This document is made available under Deposit Licence (No Weiterverbreitung - keine Bearbeitung) zur Verfügung gestellt. Redistribution - no modifications). We grant a non-exclusive, non- Gewährt wird ein nicht exklusives, nicht übertragbares, transferable, individual and limited right to using this document. persönliches und beschränktes Recht auf Nutzung dieses This document is solely intended for your personal, non- Dokuments. Dieses Dokument ist ausschließlich für commercial use. All of the copies of this documents must retain den persönlichen, nicht-kommerziellen Gebrauch bestimmt. all copyright information and other information regarding legal Auf sämtlichen Kopien dieses Dokuments müssen alle protection. You are not allowed to alter this document in any Urheberrechtshinweise und sonstigen Hinweise auf gesetzlichen way, to copy it for public or commercial purposes, to exhibit the Schutz beibehalten werden. Sie dürfen dieses Dokument document in public, to perform, distribute or otherwise use the nicht in irgendeiner Weise abändern, noch dürfen Sie document in public. dieses Dokument für öffentliche oder kommerzielle Zwecke By using this particular document, you accept the above-stated vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, aufführen, vertreiben oder conditions of use. anderweitig nutzen. Mit der Verwendung dieses Dokuments erkennen Sie die Nutzungsbedingungen an. DIE DEUTSCHEN SCHNELLDAMPFER V. -

SS Bremen (1929) 1 SS Bremen (1929)

SS Bremen (1929) 1 SS Bremen (1929) Bremen in 1931 Career (Germany) Name: SS Bremen Owner: Norddeutscher Lloyd Builder: Deutsche Schiff- und Maschinenbau Launched: 16 August 1928 Maiden voyage: 16 July 1929 Fate: Caught fire, gutted at Bremerhaven dock in 1941. Dismantled to the waterline then towed the River Weser and sunk by explosives General characteristics Tonnage: 51,656 gross tons Length: 938.6 feet (286.1 m) Beam: 101.7 feet (31 m) Installed power: Four steam turbines generating 25,000 hp (19,000 kW) each Propulsion: Quadruple propellers Speed: 27.5 knots (50.9 km/h) Capacity: 2,139; 811 first class, 500 second class, 300 tourist class, 617 third class Crew: 966 total The SS Bremen was a German-built ocean liner constructed for the Norddeutscher Lloyd line (NDL) to work the transatlantic sea route. Bremen was notable for her bulbous bow construction, high-speed engines, and low, streamlined profile. At the time of her construction, she and her sister ship Europa were the two most advanced high-speed steam turbine ocean liners of their day. The German pair sparked an international competition in the building of large, fast, luxurious ocean liners that were national symbols and points of prestige during the pre-war years of the 1930s. She held the Blue Riband, and was the fourth ship of NDL to carry the name Bremen. SS Bremen (1929) 2 History Also known as TS Bremen - for Turbine Ship - Bremen and her sister were designed to have a cruising speed of 27.5 knots, allowing a crossing time of 5 days. -

Die Deutschen Schnelldampfer. I, Die Flüsse-Klasse Des Norddeutschen Lloyd - Zaudernder Beginn Kludas, Arnold

www.ssoar.info Die deutschen Schnelldampfer. I, Die Flüsse-Klasse des Norddeutschen Lloyd - zaudernder Beginn Kludas, Arnold Veröffentlichungsversion / Published Version Zeitschriftenartikel / journal article Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Kludas, A. (1980). Die deutschen Schnelldampfer. I, Die Flüsse-Klasse des Norddeutschen Lloyd - zaudernder Beginn. Deutsches Schiffahrtsarchiv, 3, 144-170. https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-55871-1 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer Deposit-Lizenz (Keine This document is made available under Deposit Licence (No Weiterverbreitung - keine Bearbeitung) zur Verfügung gestellt. Redistribution - no modifications). We grant a non-exclusive, non- Gewährt wird ein nicht exklusives, nicht übertragbares, transferable, individual and limited right to using this document. persönliches und beschränktes Recht auf Nutzung dieses This document is solely intended for your personal, non- Dokuments. Dieses Dokument ist ausschließlich für commercial use. All of the copies of this documents must retain den persönlichen, nicht-kommerziellen Gebrauch bestimmt. all copyright information and other information regarding legal Auf sämtlichen Kopien dieses Dokuments müssen alle protection. You are not allowed to alter this document in any Urheberrechtshinweise und sonstigen Hinweise auf gesetzlichen way, to copy it for public or commercial purposes, to exhibit the Schutz beibehalten werden. Sie dürfen dieses Dokument document in public, to perform, distribute or otherwise use the nicht in irgendeiner Weise abändern, noch dürfen Sie document in public. dieses Dokument für öffentliche oder kommerzielle Zwecke By using this particular document, you accept the above-stated vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, aufführen, vertreiben oder conditions of use. anderweitig nutzen. Mit der Verwendung dieses Dokuments erkennen Sie die Nutzungsbedingungen an. DIE DEUTSCHEN SCHNELLDAMPFER VON ARNOLD KLUDAS Die Geschichte der deutschen Schnelldampfer1 vollendete sich in nur 60 Jahren. -

Norddeutscher Lloyd and Baltimore a Transatlantic Partnership

NORDDEUTSCHER LLOYD AND BALTIMORE A TRANSATLANTIC PARTNERSHIP n March 23, 1868, just more than 150 years ago, the SS Baltimore steamed past Fort Mc Henry on its maiden voyage and docked at Othe newlyconstructed immigration pier in Locust Point. The 141 passengers were the first of the 1.2 million immigrants who landed there up until 1914. The opening of the pier was the result of a partnership between the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad and the North German Lloyd Company of the port city of Bremen, which transported these immigrants across the ocean. Up to 1890, the majority of these immigrants came from Germany, adding to the substantial German presence in Baltimore. Trade connections between Baltimore and Bremen had begun in the 1790s. At that point, the U.S. had just gained its independence from Britain, and American ships were no longer limited in their destinations, which had been the case under British colonial rule. Baltimore was grow ing rapidly, the nation’s third largest city by 1810, while Bremen was also a thriving independent citystate (Germany did not unify until 1871). Baltimore merchants had established a vibrant trade with Bremen, exchanging cotton and tobacco for linen and glassware. In fact, during 1794–99, half of the American ships landing in Bremen came from Baltimore. Bremen along with Hamburg, the other major German sea port, became America’s second largest trading partner after Britain in that decade.1 The Napoleonic Wars of 1803–1815 disrupted trade, which resumed in 1815, recovering its vigorous pace. At this time, travel was entirely by sailing ships, which were usually owned by individual merchants or a partnership of merchants. -

White Star Liners White Star Liners

White Star Liners White Star Liners This document, and more, is available for download from Martin's Marine Engineering Page - www.dieselduck.net White Star Liners Adriatic I (1872-99) Statistics Gross Tonnage - 3,888 tons Dimensions - 133.25 x 12.46m (437.2 x 40.9ft) Number of funnels - 1 Number of masts - 4 Construction - Iron Propulsion - Single screw Engines - Four-cylindered compound engines made by Maudslay, Sons & Field, London Service speed - 14 knots Builder - Harland & Wolff Launch date - 17 October 1871 Passenger accommodation - 166 1st class, 1,000 3rd class Details of Career The Adriatic was ordered by White Star in 1871 along with the Celtic, which was almost identical. It was launched on 17 October 1871. It made its maiden voyage on 11 April 1872 from Liverpool to New York, via Queenstown. In May of the same year it made a record westbound crossing, between Queenstown and Sandy Hook, which had been held by Cunard's Scotia since 1866. In October 1874 the Adriatic collided with Cunard's Parthia. Both ships were leaving New York harbour and steaming parallel when they were drawn together. The damage to both ships, however, was superficial. The following year, in March 1875, it rammed and sank the US schooner Columbus off New York during heavy fog. In December it hit and sank a sailing schooner in St. George's Channel. The ship was later identified as the Harvest Queen, as it was the only ship unaccounted for. The misfortune of the Adriatic continued when, on 19 July 1878, it hit the brigantine G.A. -

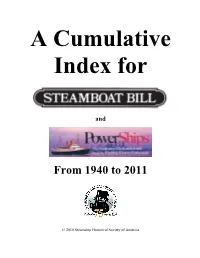

From 1940 to 2011

A Cumulative Index for and From 1940 to 2011 © 2010 Steamship Historical Society of America 2 This is a publication of THE STEAMSHIP HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF AMERICA, INC. 1029 Waterman Avenue, East Providence, RI 02914 This project has been compiled, designed and typed by Jillian Fulda, and funded by Brent and Relly Dibner Charitable Trust. 2010 TABLE OF CONTENTS Part Subject Page I Listing of whole numbers of issues, 3 with publication date of each II Feature Articles 6 III Authors of Feature Articles 42 IV Illustrations of Vessels 62 V Portraits 150 VI Other Illustrations (including cartoons) 153 VII Maps and Charts 173 VIII Fleet Lists 176 IX Regional News and Departments 178 X Reviews of Books and Other Publications 181 XI Obituaries 214 XII SSHSA Presidents 216 XIII Editors-in-Chief 216 (Please note that Steamboat Bill becomes PowerShips starting with issue #273.) 3 PART I -- WHOLE NUMBERS AND DATES (Under volume heading will follow issue number and date of publication.) VOLUME I 33 March 1950 63 September 1957 34 June 1950 64 December 1957 1 April 1940 35 September 1950 2 August 1940 36 December 1950 VOLUME XV 3 December 1940 4 April 1941 VOLUME VIII 65 March 1958 5 August 1941 66 June 1958 6 December 1941 37 March 1951 67 September 1958 7 April 1942 38 June 1951 68 December 1958 8 August 1942 39 September 1951 9 December 1942 40 December 1951 VOLUME XVI VOLUME II VOLUME IX 69 Spring 1959 70 Summer 1959 10 June 1943 41 March 1952 71 Fall 1959 11 August 1943 42 June 1952 72 Winter 1959 12 December 1943 43 September 1952 13 April 1944