Improving Livability in Northeastern Queens a Vision for Complete Streets

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Please Read the Following Carefully Before Making Your Final Selection As Custom Adventure Instructions Are Different from Previous Years

City of New York Custom Adventure Reservation Form Parks & Recreation Urban Park Rangers Please read the following carefully before making your final selection as Custom Adventure Instructions are different from previous years. Organization Name ______________________________________________________________ Address ______________________________________________________________________ City: ______________________ State _______ Zip ____________________________________ Contact Name: __________________________ Title ___________________________________ Telephone ______________________________ Fax ___________________________________ Email ________________________________________________________________________ TYPE OF PROGRAM: Custom Adventure (A maximum of 32 youth participants are allowed on each program. Each program is $250. Please note that some activities have age and location restrictions. A minimum ratio of 1 chaperone to 10 students must be maintained by the group.) Programs starting before noon will have a 60 minute break between activities. Overnight Camping Adventure (A maximum of 30 youth participants and 10 adult chaperones are allowed on each program. Each program is $500.) PROGRAM DETAILS: Requested Date(s) _______________________________________________________________ Requested Start Time: _______________ Requested Park: _________________________________ Bronx Brooklyn Manhattan Queens Staten Island PARTICIPANTS: Number of Participants: 3-7 years: _____ 8-12 years: _____ 13 – 18 years ______ Chaperones: ______ Please list -

Department of Parks Borough 0. Queens

ANNUAL REPORT OF THE DEPARTMENT OF PARKS BOROUGH 0. QUEENS CITY OF NEW YORK FOR THE YEARS 1927 AND 1928 JAMES BUTLER Comnzissioner of Parks Printed by I?. IIUBNEH& CO. N. Y. C. PARK BOARD WALTER I<. HERRICK, Presiden,t JAMES P. BROWNE JAMES BUTLER JOSEPH P. HENNESSEY JOHN J. O'ROURKE WILLISHOLLY, Secretary JULI~SBURGEVIN, Landscafe Architect DEPARTMENT OF PARKS Borough of Queens JAMES BUTLER, Commissioner JOSEPH F. MAFERA, Secretary WILLIA&l M. BLAKE, Superintendent ANTHONY V. GRANDE, Asst. Landscape Architect EDWARD P. KING, Assistant Engineer 1,OUIS THIESEN, Forester j.AMES PASTA, Chief Clerk CITY OF NEW YORK DEPARTMENT OF PARKS BOROUGHOFQUEENS March 15, 1929. Won. JAMES J. WALKER, Mayor, City of New York, City Hall, New York. Sir-In accordance with Section 1544 of the Greater New York Charter, I herewith present the Annual Report of the Department of Parks, Borough of Queens, for the two years beginning January lst, 1927, and ending December 31st, 1928. Respectfully yours, JAMES BUTLER, Commissioner. CONTENTS Page Foreword ..................................................... 7 Engineering Section ........................................... 18 Landscape Architecture Section ................................. 38 Maintenance Section ........................................... 46 Arboricultural Section ........................................ 78 Recreational Features ......................................... 80 Receipts ...................................................... 81 Budget Appropriation ....................................... -

The Reconstruction of Gender and Sexuality in a Drag Show*

DUCT TAPE, EYELINER, AND HIGH HEELS: THE RECONSTRUCTION OF GENDER AND SEXUALITY IN A DRAG SHOW* Rebecca Hanson University of Montevallo Montevallo, Alabama Abstract. “Gender blending” is found on every continent; the Hijras in India, the female husbands in Navajo society, and the travestis in Brazil exemplify so-called “third genders.” The American version of a third gender may be drag queen performers, who confound, confuse, and directly challenge commonly held notions about the stability and concrete nature of both gender and sexuality. Drag queens suggest that specific gender performances are illusions that require time and effort to produce. While it is easy to dismiss drag shows as farcical entertainment, what is conveyed through comedic expression is often political, may be used as social critique, and can be indicative of social values. Drag shows present a protest against commonly held beliefs about the natural, binary nature of gender and sexuality systems, and they challenge compulsive heterosexuality. This paper presents the results of my observational study of drag queens. In it, I describe a “routine” drag show performance and some of the interactions and scripts that occur between the performers and audience members. I propose that drag performers make dichotomous American conceptions of sexuality and gender problematical, and they redefine homosexuality and transgenderism for at least some audience members. * I would like to thank Dr. Stephen Parker for all of his support during the writing of this paper. Without his advice and mentoring I could never have started or finished this research. “Gender blending” is found on every continent. The Hijras in India, the female husbands in Navajo society, and the travestis in Brazil are just a few examples of peoples and practices that have been the subjects for “third gender” studies. -

Senior Resource Guide

New York State Assemblywoman Nily Rozic Assembly District 25 Senior Resource Guide OFFICE OF NEW YORK STATE ASSEMBLYWOMAN NILY ROZIC 25TH DISTRICT Dear Neighbor, I am pleased to present my guide for seniors, a collection of resources and information. There are a range of services available for seniors, their families and caregivers. Enclosed you will find information on senior centers, health organizations, social services and more. My office is committed to ensuring seniors are able to age in their communities with the services they need. This guide is a useful starting point and one of many steps my office is taking to ensure this happens. As always, I encourage you to contact me with any questions or concerns at 718-820-0241 or [email protected]. I look forward to seeing you soon! Sincerely, Nily Rozic DISTRICT OFFICE 159-16 Union Turnpike, Flushing, New York 11366 • 718-820-0241 • FAX: 718-820-0414 ALBANY OFFICE Legislative Office Building, Room 547, Albany, New York 12248 • 518-455-5172 • FAX: 518-455-5479 EMAIL [email protected] This guide has been made as accurate as possible at the time of printing. Please be advised that organizations, programs, and contact information are subject to change. Please feel free to contact my office at if you find information in this guide that has changed, or if there are additional resources that should be included in the next edition. District Office 159-16 Union Turnpike, Flushing, NY 11366 718-820-0241 E-mail [email protected] TABLE OF CONTENTS (1) IMPORTANT NUMBERS .............................. 6 (2) GOVERNMENT AGENCIES ........................... -

New York City Comprehensive Waterfront Plan

NEW YORK CITY CoMPREHENSWE WATERFRONT PLAN Reclaiming the City's Edge For Public Discussion Summer 1992 DAVID N. DINKINS, Mayor City of New lVrk RICHARD L. SCHAFFER, Director Department of City Planning NYC DCP 92-27 NEW YORK CITY COMPREHENSIVE WATERFRONT PLAN CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMA RY 1 INTRODUCTION: SETTING THE COURSE 1 2 PLANNING FRA MEWORK 5 HISTORICAL CONTEXT 5 LEGAL CONTEXT 7 REGULATORY CONTEXT 10 3 THE NATURAL WATERFRONT 17 WATERFRONT RESOURCES AND THEIR SIGNIFICANCE 17 Wetlands 18 Significant Coastal Habitats 21 Beaches and Coastal Erosion Areas 22 Water Quality 26 THE PLAN FOR THE NATURAL WATERFRONT 33 Citywide Strategy 33 Special Natural Waterfront Areas 35 4 THE PUBLIC WATERFRONT 51 THE EXISTING PUBLIC WATERFRONT 52 THE ACCESSIBLE WATERFRONT: ISSUES AND OPPORTUNITIES 63 THE PLAN FOR THE PUBLIC WATERFRONT 70 Regulatory Strategy 70 Public Access Opportunities 71 5 THE WORKING WATERFRONT 83 HISTORY 83 THE WORKING WATERFRONT TODAY 85 WORKING WATERFRONT ISSUES 101 THE PLAN FOR THE WORKING WATERFRONT 106 Designation Significant Maritime and Industrial Areas 107 JFK and LaGuardia Airport Areas 114 Citywide Strategy fo r the Wo rking Waterfront 115 6 THE REDEVELOPING WATER FRONT 119 THE REDEVELOPING WATERFRONT TODAY 119 THE IMPORTANCE OF REDEVELOPMENT 122 WATERFRONT DEVELOPMENT ISSUES 125 REDEVELOPMENT CRITERIA 127 THE PLAN FOR THE REDEVELOPING WATERFRONT 128 7 WATER FRONT ZONING PROPOSAL 145 WATERFRONT AREA 146 ZONING LOTS 147 CALCULATING FLOOR AREA ON WATERFRONTAGE loTS 148 DEFINITION OF WATER DEPENDENT & WATERFRONT ENHANCING USES -

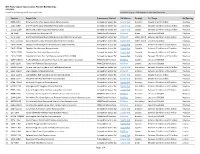

NYC Park Crime Stats

1st QTRPARK CRIME REPORT SEVEN MAJOR COMPLAINTS Report covering the period Between Jan 1, 2018 and Mar 31, 2018 GRAND LARCENY OF PARK BOROUGH SIZE (ACRES) CATEGORY Murder RAPE ROBBERY FELONY ASSAULT BURGLARY GRAND LARCENY TOTAL MOTOR VEHICLE PELHAM BAY PARK BRONX 2771.75 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00000 00 VAN CORTLANDT PARK BRONX 1146.43 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 01000 01 ROCKAWAY BEACH AND BOARDWALK QUEENS 1072.56 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00001 01 FRESHKILLS PARK STATEN ISLAND 913.32 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00000 00 FLUSHING MEADOWS CORONA PARK QUEENS 897.69 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 01002 03 LATOURETTE PARK & GOLF COURSE STATEN ISLAND 843.97 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00000 00 MARINE PARK BROOKLYN 798.00 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00000 00 BELT PARKWAY/SHORE PARKWAY BROOKLYN/QUEENS 760.43 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00000 00 BRONX PARK BRONX 718.37 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 01000 01 FRANKLIN D. ROOSEVELT BOARDWALK AND BEACH STATEN ISLAND 644.35 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00001 01 ALLEY POND PARK QUEENS 635.51 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00000 00 PROSPECT PARK BROOKLYN 526.25 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 04000 04 FOREST PARK QUEENS 506.86 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00000 00 GRAND CENTRAL PARKWAY QUEENS 460.16 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00000 00 FERRY POINT PARK BRONX 413.80 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00000 00 CONEY ISLAND BEACH & BOARDWALK BROOKLYN 399.20 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00001 01 CUNNINGHAM PARK QUEENS 358.00 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00001 01 RICHMOND PARKWAY STATEN ISLAND 350.98 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00000 00 CROSS ISLAND PARKWAY QUEENS 326.90 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00000 00 GREAT KILLS PARK STATEN ISLAND 315.09 ONE ACRE -

CBC-Ombudsman-Annual-Report

OFFICE OF THE OMBUDSMAN ENGLISH SERVICES OMBUDSMAN ANNUAL REPORT 2020-2021 June 3, 2021 Michael Goldbloom, Chairman of the Board CBC/Radio-Canada Catherine Tait, President & CEO CBC/Radio-Canada Members of the Board of Directors CBC/Radio-Canada Mr. Goldbloom, Ms. Tait and Respected Board of Directors Members: Attached please find the Annual Report of the Office of the Ombudsman, English Services for the period April 1, 2020 to March 31, 2021. Sincerely, Jack Nagler CBC Ombudsman, English Services CBC OMBUDSMAN ENGLISH SERVICES ANNUAL REPORT | 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Highlights .......................................................................................................................... 4 Trends ............................................................................................................................... 5 • The COVID-19 Pandemic ...................................................................................... 5 • Precision and Trust ............................................................................................... 6 • Accountability and Trust ........................................................................................ 7 • Inclusion and Trust ................................................................................................ 8 • Unpublishing and Trust ......................................................................................... 9 Other Issues ................................................................................................................... -

NYC Parks Capital Construction: Planned Bid Openings 5/12/2021 (Sorted by Bid Opening Month and Project Title) Contracts in Gray = Bids Opened Or Removed from Plan

NYC Parks Capital Construction: Planned Bid Openings 5/12/2021 (sorted by bid opening month and project title) contracts in gray = bids opened or removed from plan Contract Project Title Procurement Method Bid Website Borough Est. Range Bid Opening 1 B270-214M Brownsville Park Recreation Center Reconstruction Competitive Sealed Bid Capital Bids Brooklyn Greater than $10 million Apr/May 2 Q163-318M Shore Front Parkway Beach 98th Playground Construction Competitive Sealed Bid Capital Bids Queens Between $5 million and $10 million Apr/May 3 Q162E-118M Beach 59th Street Playground Reconstruction Competitive Sealed Bid Capital Bids Queens Between $5 million and $10 million May/Jun 4 XG-321M Bronx Street Tree Planting FY21 MWBE Small Purchase PASSPort Bronx Less than $500,000 May/Jun 5 R172-119M Brookfield Park Operations, Maintenance and Monitoring Services Competitive Sealed Bid PASSPort Staten Island Between $3 million and $5 million May/Jun 6 R117-117MA1 Buono Beach Fountain Reconstruction (Hurricane Sandy) Competitive Sealed Bid Capital Bids Staten Island Less than $1 million May/Jun 7 CNYG-1620M Citywide Electrical Systems Reconstruction (CNYG-1620M) Competitive Sealed Bid Capital Bids Citywide Between $1 million and $3 million May/Jun 8 CNYG-1520M Citywide Pool Electrical Reconstruction Competitive Sealed Bid Capital Bids Citywide Between $1 million and $3 million May/Jun 9 CNYG-1720M Citywide Pool Structural Reconstruction Competitive Sealed Bid Capital Bids Citywide Between $1 million and $3 million May/Jun 10 CNYG-1220M Citywide Synthetic -

Completion of Francis Lewis Boulevard, Queens

COMPLETION of FRANCIS LEWIS BOULEVARD QUEENS MIXED TRAFFIC APPROACH TO THE BRONX -WHITESTONE BRIDGE PRESIDENT BOROUGH OF QUEENS TRIBOROUGH BRIDGE AUTHORITY DEPARTMENT OF PARKS lEx ffiltbrtB SEYMOUR DURST When you leave, please leave this book Because it has been said "Sver'thing comes t' him who waits Except a loaned book." boy £5 Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library Gift of Seymour B. Durst Old York Library December 16, 1940 COMPLETION OF FRANCIS LEWIS BOULEVARD Francis Lewis Boulevard extends eleven miles across the Borough of Queens from the Belt Parkway near Rosedale at the southeasterly corner of the borough to Whitestone on the north shore. It serves as an important mixed-traffic approach to the Bronx-Whitestone Bridge and on its way across the borough taps the network of east-and-west highways and parkways leading into New York City from Long Island. At its south end it connects with the existing city street system to the Rockaways. From the standpoint of com- mercial traffic, the Boulevard provides a vital link from the south shore to upper New York City, Westchester County and Connecticut by way of the Bronx-Whitestone Bridge, Eastern Boulevard and other connecting arteries. The Topographical Bureau of the Queens Borough President's office in planning Francis Lewis Boulevard joined together several old narrow disconnected roads, some of which dated back to the Revolutionary War and appeared on maps of New York City made by the British General Sir Henry Clinton in 1781. The artery was first mapped in 1912 as Cross Island Boulevard but after the inception of Cross Island Parkway on the Belt System it was renamed in order to avoid confusion. -

Region 11: Queens

t e Road 77th e t r t S et 270th Street wl He 271st Street Langdale Street 269th Street 270th Street 78thAvenue 268th Street 77th Avenue 77th 267th Street 266th Street 76th Avenue 76th 265th Street 79thAvenue 265th Street 264th Street 85thAvenue 263rd Street e 262nd Street u n e v A 261st Street n o t 80thAvenue s Hewlett Street i l 73rd Avenue l 25B i 74th Avenue 74th EF W 60th Road 60th 260th Street t s a 60th Avenue 60th E e d u a 75th Avenue 75th n o 259th Street e 262 R nd Street Av d n h 2 t 7 260th Street 267th Street 7 Langston Avenue 258th Street 5 d 260th Street r a v e 87thAvenue l 266th Street 81stAvenue u 257th Street o t B e 83rdAvenue e e u tr c e S a a u 82ndAvenue s l th n s 5 256th Street e P 5 a v 260th Street 2 e A N 261st Street h u h t t 255th Street n 9 0 e 6 6 2 v 87th Road 58th Avenue A 254th Street h 25 t 4 2 5 th Stre 55th Street 84th Drive Little Neck Parkway et 73rd Road 7 d a Little Neck Parkway e t o 254th Street Bates Road e u R Little Neck Parkway e n e t r e u e t s v n e S r Leith Place d 254th Street 254th Street t e A d 82ndRoad e S 82nd Drive v n e 252nd Street 253rd Street ood e 2 d Glenw u 85th Road A 5 n L n 2 e v h A 252nd Street 2 t l t e t a d r B 253rd Street 6 a 7 e o 252nd Street 8 253rd Street u R 251st Street n d h e i t a e e L u v o n A e e R v le Lan 252nd Street t va h A Brow s 251st Street t e 250th Street 1 7 Elkmont Avenue Elkmont e u 7 5 k n o e r e b 251st Place v e u 60th Avenue n A n m 250th Street e a n P e L y ve c Jericho Turnpike e a a a l e e u l A w m P n u l a k l e h -

2002 NYC Cycling

A’–Œ”ˆ C•›”š˜ @C’›… š ” › • C M•”š„““ G•’‰@C’›… RŒœˆ˜@E‡Šˆ C’Œ”š•” L›‡’•ž Metro Tˆ”„‰’ North Ludlow ™ N„š›˜ˆ M•˜˜Œ™ TŒ……ˆš™ › … P„˜‘ B˜••‘ “ › ’ P„˜‘ • Y C • @ ” N ‘ ” š ˜ ˆ • •’” † ˆ ˜ ”† š K”Œ†‘ˆ˜…•†‘ˆ˜ M ™ E@LŒ ˆ ‘ Y•”‘ˆ˜™ Š – † † ” ˆ ” C•›”š˜ ’ ’ L ™ Œ R„†ˆž„ • „ • @ @ @ @ „ • ˆ † The New York Cycling Map ‹ … ‡ ˜ C’›… ž ˜ „ ” ˜ ™ Œ ‡ P ˆ L ˆ ” „ @ „ ‘ œ @ Œ • W † ˜ W Œ ’ The New York Cycling Map was developed to encourage more ‰ R B ” C „ ’Œ WŒ’™•” K ” Metro North ” š people to bicycle by identifying a network of the best streets @ ‹ @ @ @ @ @ @ @ • W••‡™@ Lower Manhatš tan & Downtown Brooklyn -- Subway and Streets ˆ Mt.Vernon West M œ George Washington Bridge ” LEGEND Nˆž@B š Y A ˜Œ‡Šˆ ’’ @ Metro North @ T „ V P„˜‘ ˆ MšN@SšN@VŒ”†ˆ”š@C•’’ˆŠˆ … ˆ rnon East ‹ ’ ˜ Mt. Ve and park paths for cycling; to educate cyclists about their rights W š 1 4 Œ“ ” „ Š Fˆˆ”ˆ Q X N HUNTERS W WRVS˜‡ K •” T œ George Washington ” Bridge - MN RV ž W 2 F 5 Q A ™ Metro North P„˜‘ Q @ E š š R Œ and responsibilities as roadway and park users; to inform ” S L ‡ POINT ™ O”M™š˜ˆˆš@…Œ‘ˆ@’„”ˆ ‹ ˜ @Q Pelham 3 V N P„˜‘™ 6 š š LŒ… ” W š ˆ ˆ P„’Œ™„‡ˆ™ S ˜š Œ ˆ ˆ ‡ ˆ ‹ ™ G W ˜ ‡ ’ • † ” œ ˜ ˆ ™ˆœ•˜š ˆ G„” ™ „ ˜ ” ’ ” … Œ ˜ ’ • „ ˜ ™ ‰ G˜„“ˆ˜† › ˆ cyclists about access to mass transit, points of interest and bike A I”šˆ˜™š„šˆ Œ Š š ˆ ˆ „ ˆ @ „ ’ Œ „ W ‡ „ ™ † ž ˜‡ LIRR ‹ „ ’ S •˜„šŒ• ˆ ‹ … ‡ @ › H ” ˆ G E ‡ ” 3 œ C ’ A ˆ š @@@@P„˜‘ ‡ ’ Rˆ†•““ˆ”‡ˆ‡@•”M™š˜ˆˆš@˜•›šˆ W P ˆ ˆ ” @ ” ˆ … Š T Œ ˆ Ÿ @ P„˜‘ … Long Island ˆ V A – ˜ D „ • ž Œ E N N @ ” L J„”ˆ ‘ – › ESTER š › Œ ˆ CH @ ‹ š EST O–ˆ”@S–„†ˆ@„”‡@†ˆ“ˆšˆ˜Œˆ™@ shops; and to recognize cycling as a legitimate mode of T W ˜ R ™ A ‡ F • ˆ ‹ Œ S ‡ S H † š „ City ” ˜ H F R P I” M œ WQ ‹ H U „ @ P ’ B Œ Š •Ÿ ˜ † ˆ A T E ’ B ˆ W Bˆˆ†‹ž••‡ ” ’ @ transportation. -

Walpole Public Library DVD List A

Walpole Public Library DVD List [Items purchased to present*] Last updated: 9/17/2021 INDEX Note: List does not reflect items lost or removed from collection A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z Nonfiction A A A place in the sun AAL Aaltra AAR Aardvark The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, ABB V.1 vol.1 The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, ABB V.2 vol.2 The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, ABB V.3 vol.3 The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, ABB V.4 vol.4 ABE Aberdeen ABO About a boy ABO About Elly ABO About Schmidt ABO About time ABO Above the rim ABR Abraham Lincoln vampire hunter ABS Absolutely anything ABS Absolutely fabulous : the movie ACC Acceptable risk ACC Accepted ACC Accountant, The ACC SER. Accused : series 1 & 2 1 & 2 ACE Ace in the hole ACE Ace Ventura pet detective ACR Across the universe ACT Act of valor ACT Acts of vengeance ADA Adam's apples ADA Adams chronicles, The ADA Adam ADA Adam’s Rib ADA Adaptation ADA Ad Astra ADJ Adjustment Bureau, The *does not reflect missing materials or those being mended Walpole Public Library DVD List [Items purchased to present*] ADM Admission ADO Adopt a highway ADR Adrift ADU Adult world ADV Adventure of Sherlock Holmes’ smarter brother, The ADV The adventures of Baron Munchausen ADV Adverse AEO Aeon Flux AFF SEAS.1 Affair, The : season 1 AFF SEAS.2 Affair, The : season 2 AFF SEAS.3 Affair, The : season 3 AFF SEAS.4 Affair, The : season 4 AFF SEAS.5 Affair,