IT IS ORDERED That Defendants' Motion to Dismiss Plaintiff's Third

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Boston University Photonics Center Annual Report 2018

Boston University Photonics Center Annual Report 2018 Letter from the Director THIS ANNUAL REPORT summarizes activities of the Boston University Photonics Center for the 2017-2018 academic year. In it, you will find quantitative and descriptive information regarding our photonics programs in education, interdisciplinary research, business innovation, and technology development. Located at the heart of Boston University’s urban campus, the Photonics Center is an interdisciplinary hub for education, research, scholarship, innovation, and technology development associated with practical uses of light. Our nine-story building houses world-class research facilities and shared laboratories dedicated to photonics research, and sustains the work of 58 faculty members, 12 staff members, and more than 100 graduate students and postdoctoral fellows. Over the past year, the Center achieved the three main goals of the strategic plan that our community committed itself to nearly six years ago. Our first strategic goal was to strengthen the Center’s research foundation, which we quantified succinctly as sustained grant income of $20M per year by Photonics Center researchers. At the time of our strategic plan, our annual grant income was about half that, and Center operations were substantially leveraged by a single DoD Technology Over the past Translation Contract that ended in 2011. In the years since, we have focused year, the Center our efforts on supporting and catalyzing new research grants by our faculty, and achieved the three the effort has paid off. Our average grant support over the past four years has main goals of the exceeded our target, and this year our grant income was about $21M. -

“Building Arizona's Future: Jobs, Innovation & Competitiveness”

“Building Arizona’s Future: Jobs, Innovation & Competitiveness” Tucson, Arizona April 25-28, 2010 Participants of the 96th Arizona Town Hall REPORT COMMITTEE Ann Hobart, Assistant Attorney General, Civil Rights Division of the Arizona Attorney General’s Office., Phoenix, Report Chair Cindy Shimokusu, Attorney, Quarles and Brady, Tucson, Co-Report Chair Matthew Bailey, Attorney, Snell & Wilmer, Phoenix Shelley DiGiacomo, Corporate Partner, Osborn Maledon, PA, Phoenix Jeremy Goodman, Attorney, Gust Rosenfeld, Phoenix Jacob Robertson, Attorney, Perkins Coie Brown & Bain P.A., Phoenix Rusty Silverstein, Attorney, Steptoe & Johnson, L.L.P., Phoenix PANEL CHAIRS Wayne Benesch, Attorney; Managing Director, Byrne, Benesch & Rice, P.C., Yuma Victor Bowleg, Mediator, Family Center of the Conciliation Court, Pima County Superior Court; Adjunct Faculty, Pima Community College, Tucson Bob Shepard, Executive Director, Sierra Vista Economic Development Foundation, Sierra Vista Ron Walker, Mohave County Manager, Kingman Kim Winzer, Chief Compliance Officer, Arizona Physicians IPA, Phoenix PLENARY SESSION PRESIDING CHAIRMAN Bruce Dusenberry, Board Chair, Arizona Town Hall; President, Horizon Moving Systems; Attorney; Tucson TOWN HALL SPEAKERS Monday morning authors’ panel presentation: Dan Hunting, Economic & Policy Analyst, Sonoran Institute, Phoenix Vera Pavlakovich-Kochi, University Associate, Senior Regional Scientist, Eller College Economic & Business Research Center; Adjunct Associate Professor, School of Geography & Development, The University -

Senior Conference 50, the Army We Need: the Role of Landpower in an Uncertain Strategic Environment, June 1-3, 2014

FOR THIS AND OTHER PUBLICATIONS, VISIT US AT UNITED STATES ARMY WAR COLLEGE http://www.carlisle.army.mil/ PRESS Carlisle Barracks, PA and SENIOR CONFERENCE 50, THE ARMY WE NEED: THE ROLE OF LANDPOWER IN AN UNCERTAIN STRATEGIC ENVIRONMENT, JUNE 1-3, 2014 U.S. ARMY WAR COLLEGE Charlie D. Lewis Rachel M. Sondheimer This Publication SSI Website USAWC Website Jeffrey D. Peterson The United States Army War College The United States Army War College educates and develops leaders for service at the strategic level while advancing knowledge in the global application of Landpower. The purpose of the United States Army War College is to produce graduates who are skilled critical thinkers and complex problem solvers. Concurrently, it is our duty to the U.S. Army to also act as a “think factory” for commanders and civilian leaders at the strategic level worldwide and routinely engage in discourse and debate concerning the role of ground forces in achieving national security objectives. The Strategic Studies Institute publishes national security and strategic research and analysis to influence policy debate and bridge the gap between military and academia. The Center for Strategic Leadership and Development CENTER for contributes to the education of world class senior STRATEGIC LEADERSHIP and DEVELOPMENT leaders, develops expert knowledge, and provides U.S. ARMY WAR COLLEGE solutions to strategic Army issues affecting the national security community. The Peacekeeping and Stability Operations Institute provides subject matter expertise, technical review, and writing expertise to agencies that develop stability operations concepts and doctrines. U.S. Army War College The Senior Leader Development and Resiliency program supports the United States Army War College’s lines of SLDR effort to educate strategic leaders and provide well-being Senior Leader Development and Resiliency education and support by developing self-awareness through leader feedback and leader resiliency. -

Building Arizona's Future

96th Arizona Town Hall April 25-28, 2010 • Tucson, Arizona Building Arizona’s Future: Jobs, Innovation & Competitiveness Background report coordinated by The University of Arizona Eller College of Management 2010-2011 ARIZONA TOWN HALL OFFICERS, BOARD OF DIRECTORS, COMMITTEE CHAIRS, AND STAFF OFFICERS EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE EX OFFICIO BRUCE L. DUSENBERRY STEVEN BETTS The Officers and the following: JOHN HAEGER Board Chair Vice Chair (Administration) LISA ATKINS JIM CONDO RON WALKER CAROL WEST GILBERT DAVIDSON Board Chair Elect Secretary LINDA ELLIOTT-NELSON KELLIE MANTHE DENNIS MITCHEM HANK PECK Vice Chair (Programs) Treasurer PAULINA VAZQUEZ MORRIS KIMULET WINZER BOARD OF DIRECTORS SAUNDRA E. JOHNSON DAVID SNIDER Principal, HRA Analysts, Inc.; Fmr. Executive Vice Member, Pinal County Board of Supervisors; Ret. City KAREN ABRAHAM President, The Flinn Foundation, Phoenix Library Director, Casa Grande Senior Vice President, Finance, Blue Cross Blue LEONARD J. KIRSCHNER JOHN W. STEBBINS Shield of Arizona, Phoenix President, AARP Arizona, Litchfield Park Controller, Freeport-McMoRan Copper & Gold, Higley ROB ADAMS JOHN E. KITAGAWA PRISCILLA STORM Mayor, City of Sedona Rector, St. Phillip's in the Hills Episcopal Church, Vice President, Public Policy & Community Planning, LARRY ALDRICH Tucson Diamond Ventures, Inc., Tucson President and CEO, University Physicians Healthcare, ARLENE KULZER ALLISON SURIANO Tucson Former President & C.E.O., Arrowhead Community Associate, Kennedy Partners, Phoenix LISA A. ATKINS Bank, Glendale GREG TOCK Vice President, Public Policy, Greater Phoenix JOSEPH E. LA RUE Publisher and Editor, The White Mountain Leadership; Board Member, Central Arizona Project, Executive Vice President, Sun Health; CEO, Sun Independent, Show Low Litchfield Park Health Partners; Attorney, Sun City PAULINA VAZQUEZ MORRIS STEVEN A. -

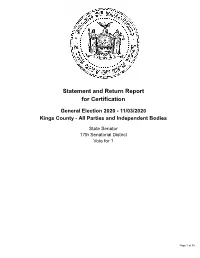

Statement and Return Report for Certification General Election 2020

Statement and Return Report for Certification General Election 2020 - 11/03/2020 Kings County - All Parties and Independent Bodies State Senator 17th Senatorial District Vote for 1 Page 1 of 38 BOARD OF ELECTIONS Statement and Return Report for Certification IN THE CITY OF NEW YORK General Election 2020 - 11/03/2020 PRINTED AS OF: Kings County 11/30/2020 5:06:41PM All Parties and Independent Bodies State Senator (17th Senatorial District), vote for 1 Assembly District 41 PUBLIC COUNTER 7,973 MANUALLY COUNTED EMERGENCY 0 ABSENTEE / MILITARY 1,654 FEDERAL 63 SPECIAL PRESIDENTIAL 0 AFFIDAVIT 86 Total Ballots 9,776 Less - Inapplicable Federal/Special Presidential Ballots (63) Total Applicable Ballots 9,713 SIMCHA FELDER (DEMOCRATIC) 2,911 SIMCHA FELDER (REPUBLICAN) 5,713 SIMCHA FELDER (CONSERVATIVE) 367 ABE LUSTASTIEN (WRITE-IN) 1 ADAM DARICK (WRITE-IN) 1 ADAM PAPISH (WRITE-IN) 1 ALAN MAISEL (WRITE-IN) 1 ALLAN FINTZ (WRITE-IN) 1 AMY CONEY BARRETT (WRITE-IN) 1 ANDLEN LANZA (WRITE-IN) 1 ANDREW GOUNARDES (WRITE-IN) 1 ANDREW LANVA (WRITE-IN) 1 ANGELA PINK (WRITE-IN) 1 ARTHUR GRUENER (WRITE-IN) 2 AUDEN PEDRENA (WRITE-IN) 1 BLAKE MORRIS (WRITE-IN) 7 CHAIM DEUTSCH (WRITE-IN) 2 CHAKA KHAN (WRITE-IN) 1 COOPER BINSKY (WRITE-IN) 1 DENIS SERDIOUK (WRITE-IN) 1 DOMINIQUE HOLNERS (WRITE-IN) 1 DONALE MAREUS (WRITE-IN) 1 DORNA YOUSEFLALEH (WRITE-IN) 1 ED JEWISKI (WRITE-IN) 1 EDWARD LAWORSKI (WRITE-IN) 4 ELLIOT SPITZER (WRITE-IN) 1 ETAI LAHAS (WRITE-IN) 1 GREGORY LEE (WRITE-IN) 1 HAROLD HERSHY TISHCHLER (WRITE-IN) 2 HAROLD HESHY TISCHLER (WRITE-IN) 2 HAROLD -

Fast and Furious: the Public Finally Needs to Know Press Conference 9:00 AM 3 July 2019 Sponsored by Precision Sign Installation

Fast And Furious: The Public Finally Needs to Know Press Conference 9:00 AM 3 July 2019 Sponsored by Precision Sign Installation Presented by Good morning and welcome to the Operation Fast and Furious – The Public Finally Needs to Know Press Conference. I am Ann Vandersteel, host of SteelTruth, an online news and investigative program. I formerly was full time with Your Voice America as most of you know and continue to enjoy a symbiotic relationship with Bill Mitchell and that fine REAL news organization. SteelTruth carries on in the same tradition, thoroughly vetting our sources and evidence, and reporting only the facts, wherever those facts may lead. Before we start, I’d like to thank our panel who travelled to be here at great cost. I’d also like to thank our sponsor Precision Sign Installation for generously making this press conference happen. Without their corporate support to cover the costs, this venue would not have been available. A special thanks to Press Club member John Milton Peterson with the American Preservation Alliance and his fantastic team he has assembled to facilitate today’s event. I would also like to thank the National Press Club and all the members of the media here today, the public who continues to show interest in getting answers to this subject, family here supporting these brave speakers and most importantly our panelist of speakers. For their stories have yet to be heard and justice yet to be served. Today’s press conference has assembled before you victims of government gone bad. They represent what happens when the power of the people is replaced with rogue operators that do not have America and her citizens best interest at heart. -

100Years of Impact

100 Years of Impact ANNUAL REPORT 2019-2020 were absolutely overwhelmed by the Wrapping up the fiscal year, we made the warmth and generosity of our community. exciting announcement of our new name With your support, we exceeded our and brand, and once again you showed us fundraising goal of $1,000,000, making such incredible support. The culmination it the most successful fundraising event of more than two years of research and in our history. Your celebratory photos planning – supported by the Graybird and video messages, and the music video Foundation – we believe the name created by adults in our performing AbilityPath better conveys our mission of Celebrating 100 Years of Impact arts program were all so inspiring. acceptance, respect, and inclusion. Dr. Temple Grandin, world-renowned What a year this has been! Last summer artists in our program share their art with This year was remarkable and memorable autism self-advocate, was a riveting we kicked off the new fiscal year by the community and sell their work. in so many ways. I hope you enjoy reading guest speaker. And one of my favorite finalizing the merger of Abilities United In the last quarter of our fiscal year we more about all we achieved together parts of each Power of Possibilities and Gatepath. I continue to be amazed had to quickly adapt to new realities on the following pages. The agility of event is the presentation of the Neal by how seamless the transition has been, due to the COVID-19 pandemic. We our team and your unwavering support Poppin Award. -

MMM MM L BEFORE the ARIZONA CORPORATION 2 COMMISSIONERS 3 TOM FORESE, Chairman BOB BURNS 4 ANDY TOBIN 5 BOYD W

. | ¥ ." 4 _. 44' f .,; 1 MM M MM M M M MMI M IM \\ M M M MM; MMMM MM l BEFORE THE ARIZONA CORPORATION 2 COMMISSIONERS 3 TOM FORESE, Chairman BOB BURNS 4 ANDY TOBIN 5 BOYD w. DUNN JUSTIN OLSON 6 7 In the matter of: Docket No. S-20932A- l5-0220 8 LOAN GO CORPORATION, a Uta 9 corporation, 10 MMELTMnNG§1;EBy'LhL'NmG3LEMw??§ HEATHE 11 JEFFREY SCOTT PETERSON, an unmarried 12 man, Arizona Corporation Commission JOHN KEITH AYERS and JENNIFER ANN 13 BRINKMAN-AYERS, husband and wife, DOCKETED 14 Respondents. NOV 27 2017 15 DOC BY 16 17 18 19 APPLICATION FOR REHEARINC ON BEHALF OF 20 JUSTIN AND HEATHER BILLINGSLEY ¢.1 . 21 November 27, 2017 A.- c . : 22 3 1 23 . ' ; \ 24 18 c i v 25 w 26 27 TABLE OF CONTENTS l 2 1. The Commission should not "bring down the hammer" on a startup just because it 3 4 11. Heather Billingsley is an innocent out-of-state spouse, and no liability startupshould be assessed against her 5 111. The Commission should not have found registration violations, because 6 the Loaf Go notes were exempt from registration ....8 7 A. The notes are exempt from registration under SEC Regulation D and 8 A.A.C. R14-4-126. 8 9 l. The subscription agreements demonstrate that Regulation D 10 l l 2. Definition of Accredited Investor under Regulation 8 12 3. The Commission's conclusion that the investors were not accredited . 13 is 9 14 4. The Commission erred as a matter of law in disregarding the investor's 15 certifications that they were accredited investors 16 5. -

List of Programmers 1 List of Programmers

List of programmers 1 List of programmers This list is incomplete. This is a list of programmers notable for their contributions to software, either as original author or architect, or for later additions. A • Michael Abrash - Popularized Mode X for DOS. This allows for faster video refresh and square pixels. • Scott Adams - one of earliest developers of CP/M and DOS games • Leonard Adleman - co-creator of RSA algorithm (the A in the name stands for Adleman), coined the term computer virus • Alfred Aho - co-creator of AWK (the A in the name stands for Aho), and main author of famous Dragon book • JJ Allaire - creator of ColdFusion Application Server, ColdFusion Markup Language • Paul Allen - Altair BASIC, Applesoft BASIC, co-founded Microsoft • Eric Allman - sendmail, syslog • Marc Andreessen - co-creator of Mosaic, co-founder of Netscape • Bill Atkinson - QuickDraw, HyperCard B • John Backus - FORTRAN, BNF • Richard Bartle - MUD, with Roy Trubshaw, creator of MUDs • Brian Behlendorf - Apache • Kent Beck - Created Extreme Programming and co-creator of JUnit • Donald Becker - Linux Ethernet drivers, Beowulf clustering • Doug Bell - Dungeon Master series of computer games • Fabrice Bellard - Creator of FFMPEG open codec library, QEMU virtualization tools • Tim Berners-Lee - inventor of World Wide Web • Daniel J. Bernstein - djbdns, qmail • Eric Bina - co-creator of Mosaic web browser • Marc Blank - co-creator of Zork • Joshua Bloch - core Java language designer, lead the Java collections framework project • Bert Bos - author of Argo web browser, co-author of Cascading Style Sheets • David Bradley - coder on the IBM PC project team who wrote the Control-Alt-Delete keyboard handler, embedded in all PC-compatible BIOSes • Andrew Braybrook - video games Paradroid and Uridium • Larry Breed - co-developer of APL\360 • Jack E. -

The Muhlenberg Network: How Connections Make a Big World Small for Alumni and Students

M621.qxp_Layout 1 6/25/18 10:59 AM Page 1 Spring/Summer 2018 The Muhlenberg Network: How Connections Make a Big World Small for Alumni and Students Invigorating a Centuries-Old Network Power Pairs: Networking in Action Fishbowl Collective Unites NYC Alumni M621.qxp_Layout 1 6/25/18 12:16 PM Page 2 SPRING/ SUMMER 2018 THE MAGAZINE The Muhlenberg College office of communications publishes Muhlenberg magazine three times a year. The guest editor and members of the communications staff write articles, unless otherwise noted. Professional photography by communications staff, Amico Studios and PaulPearsonPhoto.com unless otherwise noted. Design by Tanya Trinkle. 12 CREDITS Theatre Aboard the Disney Dream John I. Williams, Jr. PRESIDENT 1 President’s Message 37 Class Notes Bill Keller 20 Door to Door 48 In Memoriam EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR OF COMMUNICATIONS 32 Sports 53 Last Word Meghan Kita 36 SENIOR WRITER Muletin Board Jack McCallum ’71 2 Breathing New Life Into a Centuries-Old Network: Muhlenberg finds novel ways GUEST EDITOR to invest in creating connections between students, alumni, faculty, families and friends CONTACT of the College. Office of Communications 4 Career Center Looks Beyond Seegers: A major focus of the reimagined department Muhlenberg College is sponsoring professional activities that take place outside campus borders. 2400 Chew Street 8 Alumni Week: What was once a department initiative has grown to encompass more Allentown, PA 18104 than half the student body. 484-664-3230 (p) 14 Power Pairs: When an alumnus or parent helps a fellow Mule, both of them 484-664-3477 (f) reap rewards. [email protected] muhlenberg.edu 18 The Future of Professional Affinity Groups at Muhlenberg: The Career Center looks to the Wall Street Club as a model for new organizations. -

Deal Flow Report

UTAH DEAL FLOW REPORT 2015 Announcing a merger between confidence and value M & A is one of the quickest paths to growth. But it’s not always the surest. That’s why at PwC, we help you understand the risks in your transactions, so you can be confident that you are making informed strategic decisions. From your deal negotiations, to capturing synergies during integration, we help clients gain value. And ultimately, deliver this value to stakeholders. Like we’ve done for the majority of the top 50 global private equity and Fortune 100 companies. Leverage the experience of our global network of firms. For more information, contact: Ryan Dent at [email protected]/(801) 534 3883 or visit pwc.com/deals © 2016 PwC. All rights reserved. PwC refers to the PwC network and/or one or more of its member firms, each of which is a separate legal entity. Please see www.pwc.com/structure for further details. This content is for general information purposes only, and should not be used as a substitute for consultation with professional advisors. 153067-2016-MWCN Deal Flow Awards 2016 Ad.indd 1 3/18/2016 10:52:40 AM TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION Introduction ...................................................................................................................................................................................................................3 Data Findings & Conclusions.................................................................................................................................................................. -

ITC Marks the 40Th Anniversary of the Party That Changed San Antonio

The University of Texas at San Antonio Spring 2008 MAGAZINE Vol. 24, No. 2 ITC marks the 40th anniversary of the party that changed San Antonio Also in this issue: A GREENER CAMPus UNIVERSITY EXPERts TELL YOU HOW TO … SPRING 2008 TABLE OF CONTENTS FEATURES 16 HOW TO … Want to learn how to hit a home run? Need help preparing for your big job inter- view? We asked people from throughout the university to share their expertise with us, from practical matters such as how to properly wash your hands and man- age your money, to more amusing pursuits like how to win Rock, Paper, Scissors and play the bagpipes. 24 ORANGE AND BLUE AND GREEN Education programs, recycling initiatives, energy audits, a chartered energy conservation committee and signs of renewed student activism are all part of a nascent movement to make UTSA a greener, more environmentally sustainable campus. 28 SAN ANTONIO’S INTRODUCTION TO THE WORLD On the 40th anniversary of HemisFair, Sombrilla looks back at the party that changed San Antonio. UTSA’s Institute of Texan Cultures is marking the event with a yearlong exhibit. DEPARTMENTS 5 In the Loop Downtown Campus celebrates 10th anniversary; Nobel laureate begins Distinguished Lecture Series; interactive geometry exhibit helps students understand math concepts; university dedicates Kleberg Commons; social work program earns accreditation; and more campus news. 10 Investigations Physics graduate students participate in NASA small explorer mission that launches this summer; engineering professor Mo Jamshidi’s students’ robots travel by air, land and sea; and education students teach children with developmental disabilities in Motor Development Clinic.