Progress and Prospects

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Geography of Welfare in Benin, Burkina Faso, Côte D'ivoire, and Togo

Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized The Geography of Welfare in Benin, Burkina Faso, Côte d’Ivoire, and Togo Public Disclosure Authorized Nga Thi Viet Nguyen and Felipe F. Dizon Public Disclosure Authorized 00000_CVR_English.indd 1 12/6/17 2:29 PM November 2017 The Geography of Welfare in Benin, Burkina Faso, Côte d’Ivoire, and Togo Nga Thi Viet Nguyen and Felipe F. Dizon 00000_Geography_Welfare-English.indd 1 11/29/17 3:34 PM Photo Credits Cover page (top): © Georges Tadonki Cover page (center): © Curt Carnemark/World Bank Cover page (bottom): © Curt Carnemark/World Bank Page 1: © Adrian Turner/Flickr Page 7: © Arne Hoel/World Bank Page 15: © Adrian Turner/Flickr Page 32: © Dominic Chavez/World Bank Page 48: © Arne Hoel/World Bank Page 56: © Ami Vitale/World Bank 00000_Geography_Welfare-English.indd 2 12/6/17 3:27 PM Acknowledgments This study was prepared by Nga Thi Viet Nguyen The team greatly benefited from the valuable and Felipe F. Dizon. Additional contributions were support and feedback of Félicien Accrombessy, made by Brian Blankespoor, Michael Norton, and Prosper R. Backiny-Yetna, Roy Katayama, Rose Irvin Rojas. Marina Tolchinsky provided valuable Mungai, and Kané Youssouf. The team also thanks research assistance. Administrative support by Erick Herman Abiassi, Kathleen Beegle, Benjamin Siele Shifferaw Ketema is gratefully acknowledged. Billard, Luc Christiaensen, Quy-Toan Do, Kristen Himelein, Johannes Hoogeveen, Aparajita Goyal, Overall guidance for this report was received from Jacques Morisset, Elisée Ouedraogo, and Ashesh Andrew L. Dabalen. Prasann for their discussion and comments. Joanne Gaskell, Ayah Mahgoub, and Aly Sanoh pro- vided detailed and careful peer review comments. -

Cycles Approved by OHRM for S

Consolidated list of duty stations approved by OHRM for rest and recuperation (R & R) (as of 1 July 2015) Duty Station Frequency R & R Destination AFGHANISTAN Entire country 6 weeks Dubai ALGERIA Tindouf 8 weeks Las Palmas BURKINA FASO Dori 12 weeks Ouagadougou BURUNDI Bujumbura, Gitega, Makamba, Ngozi 8 weeks Nairobi CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC Entire country 6 weeks Yaoundé CHAD Abeche, Farchana, Goré, Gozbeida, Mao, N’Djamena, Sarh 8 weeks Addis Ababa COLOMBIA Quibdo 12 weeks Bogota COTE D’IVOIRE Entire country except Abidjan and Yamoussoukro 8 weeks Accra DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO Aru, Beni, Bukavu, Bunia, Butembo, Dungu, Goma, Kalemie, Mahagi, Uvira 6 weeks Entebbe Bili, Bandundu, Gemena, Kamina, Kananga, Kindu, Kisangani, Matadi, Mbandaka, Mbuji-Mayi 8 weeks Entebbe Lubumbashi 12 weeks Entebbe DEMOCRATIC PEOPLE’S REPUBLIC OF KOREA Pyongyang 8 weeks Beijing ETHIOPIA Kebridehar 6 weeks Addis Ababa Jijiga 8 weeks Addis Ababa GAZA Gaza (entire) 8 weeks Amman GUINEA Entire country 6 weeks Accra HAITI Entire country 8 weeks Santo Domingo INDONESIA Jayapura 12 weeks Jakarta IRAQ Baghdad, Basrah, Kirkuk, Dohuk 4 weeks Amman Erbil, Sulaymaniah 8 weeks Amman KENYA Dadaab, Wajir, Liboi 6 weeks Nairobi Kakuma 8 weeks Nairobi KYRGYZSTAN Osh 8 weeks Istanbul LIBERIA Entire country 8 weeks Accra LIBYA Entire country 6 weeks Malta MALI Gao, Kidal, Tesalit 4 weeks Dakar Tombouctou, Mopti 6 weeks Dakar Bamako, Kayes 8 weeks Dakar MYANMAR Sittwe 8 weeks Yangon Myitkyina (Kachin State) 12 weeks Yangon NEPAL Bharatpur, Bidur, Charikot, Dhunche, -

The Case of African Cities

Towards Urban Resource Flow Estimates in Data Scarce Environments: The Case of African Cities The MIT Faculty has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters. Citation Currie, Paul, et al. "Towards Urban Resource Flow Estimates in Data Scarce Environments: The Case of African Cities." Journal of Environmental Protection 6, 9 (September 2015): 1066-1083 © 2015 Author(s) As Published 10.4236/JEP.2015.69094 Publisher Scientific Research Publishing, Inc, Version Final published version Citable link https://hdl.handle.net/1721.1/124946 Terms of Use Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license Detailed Terms https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Journal of Environmental Protection, 2015, 6, 1066-1083 Published Online September 2015 in SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/jep http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/jep.2015.69094 Towards Urban Resource Flow Estimates in Data Scarce Environments: The Case of African Cities Paul Currie1*, Ethan Lay-Sleeper2, John E. Fernández2, Jenny Kim2, Josephine Kaviti Musango3 1School of Public Leadership, Stellenbosch University, Stellenbosch, South Africa 2Department of Architecture, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, USA 3School of Public Leadership, and the Centre for Renewable and Sustainable Energy Studies (CRSES), Stellenbosch, South Africa Email: *[email protected] Received 29 July 2015; accepted 20 September 2015; published 23 September 2015 Copyright © 2015 by authors and Scientific Research Publishing Inc. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY). http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Abstract Data sourcing challenges in African nations have led many African urban infrastructure develop- ments to be implemented with minimal scientific backing to support their success. -

See Full Prospectus

G20 COMPACT WITHAFRICA CÔTE D’IVOIRE Investment Opportunities G20 Compact with Africa 8°W To 7°W 6°W 5°W 4°W 3°W Bamako To MALI Sikasso CÔTE D'IVOIRE COUNTRY CONTEXT Tengrel BURKINA To Bobo Dioulasso FASO To Kampti Minignan Folon CITIES AND TOWNS 10°N é 10°N Bagoué o g DISTRICT CAPITALS a SAVANES B DENGUÉLÉ To REGION CAPITALS Batie Odienné Boundiali Ferkessedougou NATIONAL CAPITAL Korhogo K RIVERS Kabadougou o —growth m Macroeconomic stability B Poro Tchologo Bouna To o o u é MAIN ROADS Beyla To c Bounkani Bole n RAILROADS a 9°N l 9°N averaging 9% over past five years, low B a m DISTRICT BOUNDARIES a d n ZANZAN S a AUTONOMOUS DISTRICT and stable inflation, contained fiscal a B N GUINEA s Hambol s WOROBA BOUNDARIES z a i n Worodougou d M r a Dabakala Bafing a Bere REGION BOUNDARIES r deficit; sustainable debt Touba a o u VALLEE DU BANDAMA é INTERNATIONAL BOUNDARIES Séguéla Mankono Katiola Bondoukou 8°N 8°N Gontougo To To Tanda Wenchi Nzerekore Biankouma Béoumi Bouaké Tonkpi Lac de Gbêke Business friendly investment Mont Nimba Haut-Sassandra Kossou Sakassou M'Bahiakro (1,752 m) Man Vavoua Zuenoula Iffou MONTAGNES To Danane SASSANDRA- Sunyani Guemon Tiebissou Belier Agnibilékrou climate—sustained progress over the MARAHOUE Bocanda LACS Daoukro Bangolo Bouaflé 7°N 7°N Daloa YAMOUSSOUKRO Marahoue last four years as measured by Doing Duekoue o Abengourou b GHANA o YAMOUSSOUKRO Dimbokro L Sinfra Guiglo Bongouanou Indenie- Toulepleu Toumodi N'Zi Djuablin Business, Global Competitiveness, Oumé Cavally Issia Belier To Gôh CÔTE D'IVOIRE Monrovia -

Concept Note

Under the High patronage of the President of Ivory Coast « Peace in the mind of men and women » CELEBRATION OF 25 YEARS OF THE CONCEPT OF CULTURE OF PEACE LAUNCHING OF THE ACTIVITIES OF THE NETWORK FOUNDATIONS AND RESEARCH INSTITUTIONS FOR THE PROMOTION OF A CULTURE OF PEACE IN AFRICA YAMOUSSOUKRO, 21-22-23 SEPTEMBER 2014 Peace is reverence for life. Peace is the most precious possession of humanity. Peace is more than the end of armed conflict. Peace is a mode of behaviour. Peace is a deep-rooted commitment to the principles of liberty, justice, equality and solidarity among all human beings. Peace is also a harmonious partnership of humankind with the environment. Today, on the eve of the twenty-first century, peace is within our reach. Preamble of Yamoussoukro declaration on peace in the mind of men, 1989 1 Introduction: the increased relevance of the concept of culture of peace in Africa Twenty-five years after the International Congress of UNESCO held in Yamoussoukro (Ivory Coast) on the theme "Peace in the minds of men", that gave birth in 1989 to the concept of culture of peace, the UNESCO and the Félix Houphouët-Boigny Foundation for peace research will jointly celebrate this anniversary in Yamoussoukro from 21 to 23 September 2014. This event, under the High patronage of the President of Ivory Coast, has two objectives, the first being to measure the progress made since 1989 geared towards the implementation of this concept and the second, to explore future avenues, in particular, by launching the activities of the Network of foundations and research institutions for the promotion of a culture of peace in Africa, established in September 2013 in Addis Ababa. -

1 Ccr 101-1 State Fiscal Rules 2 (Pdf)

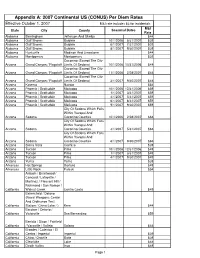

Appendix A: 2007 Continental US (CONUS) Per Diem Rates Effective October 1, 2007 M&I rate includes $3 for incidentals M&I State City County Seasonal Dates Rate Alabama Birmingham Jefferson And Shelby $44 Alabama Gulf Shores Baldwin 10/1/2006 5/31/2007 $39 Alabama Gulf Shores Baldwin 6/1/2007 7/31/2007 $39 Alabama Gulf Shores Baldwin 8/1/2007 9/30/2007 $39 Alabama Huntsville Madison And Limestone $44 Alabama Montgomery Montgomery $39 Coconino (Except The City Arizona Grand Canyon / Flagstaff Limits Of Sedona) 10/1/2006 10/31/2006 $44 Coconino (Except The City Arizona Grand Canyon / Flagstaff Limits Of Sedona) 11/1/2006 2/28/2007 $44 Coconino (Except The City Arizona Grand Canyon / Flagstaff Limits Of Sedona) 3/1/2007 9/30/2007 $44 Arizona Kayenta Navajo $54 Arizona Phoenix / Scottsdale Maricopa 10/1/2006 12/31/2006 $59 Arizona Phoenix / Scottsdale Maricopa 1/1/2007 3/31/2007 $59 Arizona Phoenix / Scottsdale Maricopa 4/1/2007 5/31/2007 $59 Arizona Phoenix / Scottsdale Maricopa 6/1/2007 8/31/2007 $59 Arizona Phoenix / Scottsdale Maricopa 9/1/2007 9/30/2007 $59 City Of Sedona Which Falls Within Yavapai And Arizona Sedona Coconino Counties 10/1/2006 2/28/2007 $64 City Of Sedona Which Falls Within Yavapai And Arizona Sedona Coconino Counties 3/1/2007 5/31/2007 $64 City Of Sedona Which Falls Within Yavapai And Arizona Sedona Coconino Counties 6/1/2007 9/30/2007 $64 Arizona Sierra Vista Cochise $39 Arizona Tucson Pima 10/1/2006 12/31/2006 $49 Arizona Tucson Pima 1/1/2007 3/31/2007 $49 Arizona Tucson Pima 4/1/2007 9/30/2007 $49 Arizona Yuma Yuma -

![Downloadable from the NASA LANCE FIRMS Website [73,74]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3440/downloadable-from-the-nasa-lance-firms-website-73-74-1843440.webp)

Downloadable from the NASA LANCE FIRMS Website [73,74]

fire Article Predictive Modeling of Wildfire Occurrence and Damage in a Tropical Savanna Ecosystem of West Africa Jean-Luc Kouassi 1,* , Narcisse Wandan 1 and Cheikh Mbow 2 1 Laboratoire Science Société et Environnement (LSSE), Unité Mixte de Recherche et d’Innovation Sciences Agronomiques et Génie Rural, Institut National Polytechnique Félix Houphouët-Boigny (INP-HB), P.O. Box 1093, Yamoussoukro 10010202, Côte d’Ivoire; [email protected] 2 Future Africa, University of Pretoria, South St, Koedoespoort 456-Jr, Pretoria 0002, South Africa; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +225-0742-1858 Received: 30 May 2020; Accepted: 7 August 2020; Published: 12 August 2020 Abstract: Wildfires are a major environmental, economic, and social threat. In Central Côte d’Ivoire, they are among the biggest environmental and forestry problems during the dry season. National authorities do not have tools and methods to predict spatial and temporal fire proneness over large areas. This study, based on the use of satellite historical data, aims to develop an appropriate model to forecast wildfire occurrence and burnt areas in each ecoregion of the N’Zi River Watershed. We used an autoregressive integrated moving average (ARIMA) model to simulate and forecast the number of wildfires and burnt area time series in each ecoregion. Nineteen years of monthly datasets were trained and tested. The model performance assessment combined Ljung–Box statistics, residuals, and autocorrelation analysis coupled with cross-validation using three forecast errors—namely, root mean square error, mean absolute error, and mean absolute scaled error—and observed–simulated data analysis. The results showed that the ARIMA models yielded accurate forecasts of the test dataset in all ecoregions and highlighted the effectiveness of the ARIMA models to forecast the total number of wildfires and total burnt area estimation in the future. -

WEST AFRICA LIBYA 25° ALGERIA 25° WEST Western AFRICA Sahara Tamanrasset Fdérik

20° 15° 10° 5° 0° 5° 10° 15° WEST AFRICA LIBYA 25° ALGERIA 25° WEST Western AFRICA Sahara Tamanrasset Fdérik Nouâdhibou Atâr 20° Akjoujt MAURITANIA 20° Tidjikja Kidal Nouakchott MALI A NIGER T Aleg Tombouctou Agadez Rosso Sene Kiffa 'Ayoûn el 'Atroûs gal L Gao Kaédi Saint-Louis A Louga Matam Sélibabi Tahoua 15° N Dakar Lake 15° Kayes Chad Kaolack SENEGAL Tillabéri T Mopti mbia Tambacounda Zinder CHAD Ga er Niamey Maradi I ig Diffa GAMBIA N Ségou BURKINA Dosso Sokoto C Banjul Kolda Koulikoro FASO Dédougou Katsina Ziguinchor Bamako Ouagadougou Kano Bissau Birnin Kebbi Gusau Maiduguri Koudougou Fada Dutse GUINEA-BISSAU Bobo- N'Gourma Niger Labé Sikasso Dioulasso Boké Léo Kandi O Mamou Kankan Banfora Kaduna Maroua GUINEA Bolgatanga Bauchi C Kindia BENIN Gombe Wa Jos 10° Faranah Odienné Kara Djougou NIGERIA 10° E Conakry Tamale e Kissidougou Lake Abuja nu Yola A Forécariah SIERRA Korhogo e Makeni Volta B Garoua Guéckédou Ilorin Lafia N Freetown Macenta Touba CÔTE Jalingo LEONE Bo Voinjama Nzérékoré D'IVOIRE Lac de GHANA Ado-Ekiti Makurdi Kenema ManKossou Bouaké TOGO Ibadan Ngaoundéré 25° 24° Sunyani Abomey Yamoussoukro Abeokuta CABO VERDE Dimbokro Santo Antão Robertsport LIBERIA Kumasi Cotonou Ikeja Daloa Lagos Benin City Enugu 17° 17° Monrovia Kakata Ho Santa Luzia Zwedru Guiglo Divo Koforidua Porto- Bamenda São Sal Gagnoa Buchanan Lomé Novo Owerri Bafoussam Vicente Fish Town Accra São Nicolau Cestos City Bight of Benin Calabar 5° Port 5° Greenville Abidjan Cape Harcourt CAMEROON Boa Vista Sekondi- Coast 16° 16° Barclayville San-Pédro Buea ATLANTIC Harper Takoradi Douala Yaoundé OCEAN Malabo São 0 100 200 300 400 500 km 0 50 km The boundaries and names shown and the designations used Tiago EQUATORIAL GUINEA Ébolowa 0 25 mi Maio on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance Fogo by the United Nations. -

Côte D'ivoire Habitat Côte D´Ivoire

Country profile Côte d’Ivoire COUNTRY FACTS* Capital Yamoussoukro Habitat for Humanity in Côte d’Ivoire Date of 1960 independence Established in 1999, Habitat for Humanity Côte d’Ivoire works with homeowners to build safe, dry and secure homes, with decent sanitation. Population 23.1 million Spain Turkey Italy Portugal Greece Athens Nicosia The housing need in Côte d’Ivoire Urbanization 49.7% Cyprus In 2015, the cumulative housing deficit in Cote d’Ivoire was estimated at 1 Life 58 years Gibraltar Algiers million. In the city of Abidjan alone, the housing deficit grows from 40,000 expectancy Tunis Malta to 50,000 units per year. In Abidjan, 3,000 units are supplied annually. Valletta Rabat The government stopped subsidizing housing in 1995, contributing to the Unemployment 6.9% acute housing deficit. rate Morocco Tunisia Population 46.3% Tripoli living below the In rural areas, 90 percent of the people live in temporary structures, which poverty line Cairo require extensive upkeep and repair. Walls are typically made of mud in a wooden frame and they often crack, causing leaks and eventually falling * Find more country facts on: apart. Thatch-roof houses harbor numerous disease-carrying insects, CIA The World Factbook – Cote d’Ivoire such as malarial mosquitoes and the tsetse fly, which can spread eye Algeria disease. The lack of latrines and water facilities were found to be a major challenge. Only 18.1 percent of the households possess a pit latrine, 39 E gypt percent practice open defecation, and 92.5 percent use unsafe drinking HABITAT FACTS Libya water (MICS 2016). -

The Yamoussoukro Declaration on Peace in The

YAMOUSSOUKRO DECLARATION ON PEACE IN THE MINDS OF MEN I Peace is reverence for life. Peace is the most precious possession of humanity. Peace is more than the end of armed conflict. Peace is a mode of behaviour. Peace is a deep-rooted commitment to the principles of liberty, justice, equality and solidarity among all human beings. Peace is also a harmonious partnership of humankind with the environment. Today, on the eve of the twenty-first century, peace is within our reach. * * * The International Congress on Peace in the Minds of Men, held on the initiative of UNESCO in Yamoussoukro in the heart of Africa, the cradle of humanity and yet a land of suffering and unequal development, brought together from the five continents men and women who dedicate themselves to the cause of peace. The growing interdependence between nations and the increasing awareness of common security are signs of hope. Disarmament measures helping to lessen tensions have been announced and already taken by some countries. Progress is being made in the peaceful settlement of international disputes. There is wider recognition of the international machinery for the protection of human rights. But the Congress also noted the persistence of various armed conflicts throughout the world. There are also other conflictual situations: apartheid in South Africa; non-respect for national integrity; racism, intolerance and discrimination, particularly against women; and above all economic pressures in all their forms. In addition, the Congress noted the emergence of new, non-military -

Land Use/Land Cover Patterns and Challenges to Sustainable Management of the Mono Transboundary Biosphere Reserve Between Togo and Benin, West Africa

Available online at http://www.ifgdg.org Int. J. Biol. Chem. Sci. 14(5): 1734-1751, June 2020 ISSN 1997-342X (Online), ISSN 1991-8631 (Print) Original Paper http://ajol.info/index.php/ijbcs http://indexmedicus.afro.who.int Land use/land cover patterns and challenges to sustainable management of the Mono transboundary biosphere reserve between Togo and Benin, West Africa Kossi ADJONOU1*, Issa Adbou-Kérim BINDAOUDOU 2, Kossi Novinyo SEGLA1, IDOHOU Rodrigue3, Kolawole Valère SALAKO 3, Romain GLELE-KAKAÏ3 and Kouami KOKOU1 1 Faculté des Sciences, Université de Lomé ; 01 BP : 1515 Lome, Togo. 2 Centre Universitaire de Recherche et d’Application en Télédétection, Université Félix HOUPHOUËT- BOIGNY, 01 BPV 34 Abidjan 01, Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire. 3 Faculté des Sciences Agronomiques, Université d’Abomey-Calavi, 03 B.P. 2819, Cotonou – Bénin. *Corresponding author; E-mail: [email protected] ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This work was supported by: Central and West African Forest Space Observation Project (OSFACO) of Research Institute for Development (IRD) and French Agency for Development (AFD); Mono Delta Transborder Biosphere Reserve Project between Togo and Benin (ProMono) of the German international cooperation agency for international development (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit GIZ) for funding this research. ABSTRACT The Mono Transboundary Biosphere Reserve (RBTM) has significant resources but faces many threats that lead to habitat fragmentation and reduction of ecosystem services. This study, based on satellite image analysis and processing, was carried out to establish the baseline of land cover and land use status and to analyze their dynamics over the period 1986 to 2015. The baseline of land cover established six categories of land use including wetlands (45.11%), mosaic crops/fallow (25.99%), savannas (17.04%), plantation (5.50%), agglomeration/bare soil (4.38%) and dense forest (1.98%). -

Opening African Skies: the Case of Airline Industry Liberalization in East Africa Author(S): Evaristus M

Transportation Research Forum Opening African Skies: The Case of Airline Industry Liberalization in East Africa Author(s): Evaristus M. Irandu Source: Journal of the Transportation Research Forum, Vol. 47, No. 1 (Spring 2008), pp. 73-88 Published by: Transportation Research Forum Stable URL: http://www.trforum.org/journal The Transportation Research Forum, founded in 1958, is an independent, nonprofit organization of transportation professionals who conduct, use, and benefit from research. Its purpose is to provide an impartial meeting ground for carriers, shippers, government officials, consultants, university researchers, suppliers, and others seeking exchange of information and ideas related to both passenger and freight transportation. More information on the Transportation Research Forum can be found on the Web at www.trforum.org. OPENING AFRICAN SKIES: THE CASE OF AIRLINE INDUSTRY LIBERALIZATION IN EAST AFRICA by Evaristus M. Irandu The three member states of the East African Community (EAC) have made great efforts in modernizing their air transport industry in order to meet the increased demand for international tourism and horticultural export trade. The policy adopted by the sub-region, at independence, to regulate the airline industry was the bilateralism approach with emphasis on reciprocity. Such a policy became a bottleneck in the development of the air transport industry in the sub-region. It became apparent that the EAC member states needed efficient air services and not airlines that served mainly as status symbols. However, the last decade witnessed the liberalization of the aviation sector in the sub-region. This liberalization process is part of a proactive policy to encourage global investment in the sub-region.