The Contributions of Blacks in Akron: 1825-1975

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE ERADICATION of POLIOMYELITIS (Fhe Albert V.• Sabin Lecture)

THE ERADICATIONOF POLIOMYELITIS (fhe Albert V.•Sabin Lecture) by Donald Henderson, M.D., M.P.H. University Distinguished Service Professor The JohnsHopkins University Baltimore, Maryland 21205 Cirode Quadros, M.D., M.P.H. Regional Advisor Expanded Programme on lmmunii.ation Pan American Health Organization 525 23rd Street, N. W. Washington, D.C. 20037 Introduction The understanding and ultimate conquest of poliomyelitis was Albert Sabin's life long preoccupation, beginning with his earliest work in 1931. (Sabin and Olitsky, 1936; Sabin, 1965) The magnitude of that effort was aptly summarized by Paul in his landmark history of polio: "No man has ever contributed so much effective information - and so continuously over so many years - to so many aspects of poliomyelitis." (Paul, 1971) Thus, appropriately, this inaugural Sabin lecture deals with poliomyelitis and its eradication. Polio Vaccine Development and Its Introduction In the quest for polio control and ultimately eradication, several landmarks deserve special mention. At the outset, progress was contingent on the development of a vaccine and the production of a vaccine, in turn, necessitated the discovery of new methods to grow large quantities of virus. The breakthrough occurred in 1969 when Enders and his colleagues showed that large quantities of poliovirus could be grown in a variety of human cell tissue cultures and that the virus could be quantitatively assayed by its cytopathic effect. (Enders, Weller and Robbins, 1969) Preparation of an inactivated vaccine was, in principle, a comparatively straightforward process. In brief, large quantities of virus were grown. then purified, inactivated with formalin and bottled. Assurance that the virus had been inactivated could be demonstrated by growth in tissue. -

Hidden Cargo: a Cautionary Tale About Agroterrorism and the Safety of Imported Produce

HIDDEN CARGO: A CAUTIONARY TALE ABOUT AGROTERRORISM AND THE SAFETY OF IMPORTED PRODUCE 1. INTRODUCTION The attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon on Septem ber 11, 2001 ("9/11") demonstrated to the United States ("U.S.") Gov ernment the U.S. is vulnerable to a wide range of potential terrorist at tacks. l The anthrax attacks that occurred immediately following the 9/11 attacks further demonstrated the vulnerability of the U.S. to biological attacks. 2 The U.S. Government was forced to accept its citizens were vulnerable to attacks within its own borders and the concern of almost every branch of government turned its focus toward reducing this vulner ability.3 Of the potential attacks that could occur, we should be the most concerned with biological attacks on our food supply. These attacks are relatively easy to initiate and can cause serious political and economic devastation within the victim nation. 4 Generally, acts of deliberate contamination of food with biological agents in a terrorist act are defined as "bioterrorism."5 The World Health Organization ("WHO") uses the term "food terrorism" which it defines as "an act or threat of deliberate contamination of food for human con- I Rona Hirschberg, John La Montagne & Anthony Fauci, Biomedical Research - An Integral Component of National Security, NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE (May 20,2004), at 2119, available at http://contenLnejrn.org/cgi/reprint/350/2112ll9.pdf (dis cussing the vulnerability of the U.S. to biological, chemical, nuclear, and radiological terrorist attacks). 2 Id.; Anthony Fauci, Biodefence on the Research Agenda, NATURE, Feb. -

John Brown and George Kellogg

John Brown and George Kellogg By Jean Luddy When most people think of John Brown, they remember the fiery abolitionist who attacked pro-slavery settlers in Kansas in 1855 and who led the raid on the Federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry, Virginia in 1859 in order to spark a slave rebellion. Most people do not realize that Brown was no stranger to Vernon and Rockville, and that he worked for one of Rockville’s prominent 19th century citizens, George Kellogg. John Brown was born in Torrington, CT in 1800. His father was a staunch opponent of slavery and Brown spent his youth in a section of northern Ohio known as an abolitionist district. Before Brown became actively involved in the movement to eliminate slavery, he held a number of jobs, mainly associated with farming, land speculation and wool growing. (www.pbs.org) Brown’s path crossed with George Kellogg’s when Brown started to work for Kellogg and the New England Company as a wool sorter and buyer. John Brown George Kellogg, born on March 3, 1793 in Vernon, got his start in the woolen industry early in life when he joined Colonel Francis McLean in business in 1821. They established the Rock Manufacturing Company and built the Rock Mill, the first factory along the Hockanum River, in the area that would grow into the City of Rockville. Kellogg worked as the company’s agent from 1828 to 1837. At that time, he left the Rock Company to go into business with Allen Hammond. They founded the New England Company and built a factory along the Hockanum River. -

Qlikview Customer Snapshot – Akron Beacon Journal

QlikView Customer Snapshot – Akron Beacon Journal Challenges • Gain visibility into performance of advertising sales teams • Identify opportunities for revenue growth in advertising among Leveraging QlikView through Mactive Analytix to mix of customers, ad type, product, placements etc. analyze financials and advertising revenue across ad type, placement, product, sales team and sales rep – Solution all focused on driving ad revenue growth. • Deployed QlikView to 136 users across 2 functions in US: Financial Analysis: -Measure advertising revenue by GL to provide actual versus budget, and grouped by revenue category, revenue type or customer -Measure revenue performance with variances by orders, customers and sales rep Sales Advertising Analysis: -Assess sales rep performance for all charges on an ad and any credits/debits directed down to the insertion level; -Analyze order details in revenue and inches per insertion grouped by ad number, position, placement, product, customer type and by rep -Monitor average ad rate grouped by placement, ad type, product, sales About Akron Beacon Journal team and sales rep • Ohio's only four-time Pulitzer Prize-winning newspaper, serves • Leveraged Mactive Analytix (QlikView) to aggregate modest readers in Summit, Portage, Stark, Medina and Wayne counties data volumes from Mactive Finance and Sales solutions • Delivers daily news and information in print and online at Ohio.com. The largest newspaper of Canada-based Black Benefits Press Ltd., the Akron Beacon Journal operates under Sound • Improved ad revenue growth from improved visibility into Publishing Holdings Inc., the parent company's Washington- operations and sales activities based U.S. subsidiary • Gained ability to drill down into the data to effectively manage • Daily circulation of more than 122,000 the business and make informed and timely decisions • Headquartered in Akron, Ohio • Saved time and effort of business and IT team in automating • Industry: Media and simplifying analysis and reporting. -

Teen Stabbing Questions Still Unanswered What Motivated 14-Year-Old Boy to Attack Family?

Save $86.25 with coupons in today’s paper Penn State holds The Kirby at 30 off late Honoring the Center’s charge rich history and its to beat Temple impact on the region SPORTS • 1C SPECIAL SECTION Sunday, September 18, 2016 BREAKING NEWS AT TIMESLEADER.COM '365/=[+<</M /88=C6@+83+sǍL Teen stabbing questions still unanswered What motivated 14-year-old boy to attack family? By Bill O’Boyle Sinoracki in the chest, causing Sinoracki’s wife, Bobbi Jo, 36, ,9,9C6/Ľ>37/=6/+./<L-97 his death. and the couple’s 17-year-old Investigators say Hocken- daughter. KINGSTON TWP. — Specu- berry, 14, of 145 S. Lehigh A preliminary hearing lation has been rampant since St. — located adjacent to the for Hockenberry, originally last Sunday when a 14-year-old Sinoracki home — entered 7 scheduled for Sept. 22, has boy entered his neighbors’ Orchard St. and stabbed three been continued at the request house in the middle of the day members of the Sinoracki fam- of his attorney, Frank Nocito. and stabbed three people, kill- According to the office of ing one. ily. Hockenberry is charged Magisterial District Justice Everyone connected to the James Tupper and Kingston case and the general public with homicide, aggravated assault, simple assault, reck- Township Police Chief Michael have been wondering what Moravec, the hearing will be lessly endangering another Photo courtesy of GoFundMe could have motivated the held at 9:30 a.m. Nov. 7 at person and burglary in connec- In this photo taken from the GoFundMe account page set up for the Sinoracki accused, Zachary Hocken- Tupper’s office, 11 Carverton family, David Sinoracki is shown with his wife, Bobbi Jo, and their three children, berry, to walk into a home on tion with the death of David Megan 17; Madison, 14; and David Jr., 11. -

“I Woke up to the World”: Politicizing Blackness and Multiracial Identity Through Activism

“I woke up to the world”: Politicizing Blackness and Multiracial Identity Through Activism by Angelica Celeste Loblack A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Sociology College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Elizabeth Hordge-Freeman, Ph.D. Beatriz Padilla, Ph.D. Jennifer Sims, Ph.D. Date of Approval: March 3, 2020 Keywords: family, higher education, involvement, racialization, racial socialization Copyright © 2020, Angelica Celeste Loblack TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Tables ............................................................................................................................ iii Abstract ..................................................................................................................................... iv Introduction: Falling in Love with my Blackness ........................................................................ 1 Black while Multiracial: Mapping Coalitions and Divisions ............................................ 5 Chapter One: Literature Review .................................................................................................. 8 Multiracial Utopianism: (Multi)racialization in a Colorblind Era ..................................... 8 I Am, Because: Multiracial Pre-College Racial Socialization ......................................... 11 The Blacker the Berry: Racialization and Racial Fluidity ............................................... 15 Racialized Bodies: (Mono)racism -

Abraham Lincoln, Kentucky African Americans and the Constitution

Abraham Lincoln, Kentucky African Americans and the Constitution Kentucky African American Heritage Commission Abraham Lincoln Bicentennial Collection of Essays Abraham Lincoln, Kentucky African Americans and the Constitution Kentucky African American Heritage Commission Abraham Lincoln Bicentennial Collection of Essays Kentucky Abraham Lincoln Bicentennial Commission Kentucky Heritage Council © Essays compiled by Alicestyne Turley, Director Underground Railroad Research Institute University of Louisville, Department of Pan African Studies for the Kentucky African American Heritage Commission, Frankfort, KY February 2010 Series Sponsors: Kentucky African American Heritage Commission Kentucky Historical Society Kentucky Abraham Lincoln Bicentennial Commission Kentucky Heritage Council Underground Railroad Research Institute Kentucky State Parks Centre College Georgetown College Lincoln Memorial University University of Louisville Department of Pan African Studies Kentucky Abraham Lincoln Bicentennial Commission The Kentucky Abraham Lincoln Bicentennial Commission (KALBC) was established by executive order in 2004 to organize and coordinate the state's commemorative activities in celebration of the 200th anniversary of the birth of President Abraham Lincoln. Its mission is to ensure that Lincoln's Kentucky story is an essential part of the national celebration, emphasizing Kentucky's contribution to his thoughts and ideals. The Commission also serves as coordinator of statewide efforts to convey Lincoln's Kentucky story and his legacy of freedom, democracy, and equal opportunity for all. Kentucky African American Heritage Commission [Enabling legislation KRS. 171.800] It is the mission of the Kentucky African American Heritage Commission to identify and promote awareness of significant African American history and influence upon the history and culture of Kentucky and to support and encourage the preservation of Kentucky African American heritage and historic sites. -

Minority Percentages at Participating Newspapers

Minority Percentages at Participating Newspapers Asian Native Asian Native Am. Black Hisp Am. Total Am. Black Hisp Am. Total ALABAMA The Anniston Star........................................................3.0 3.0 0.0 0.0 6.1 Free Lance, Hollister ...................................................0.0 0.0 12.5 0.0 12.5 The News-Courier, Athens...........................................0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 Lake County Record-Bee, Lakeport...............................0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 The Birmingham News................................................0.7 16.7 0.7 0.0 18.1 The Lompoc Record..................................................20.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 20.0 The Decatur Daily........................................................0.0 8.6 0.0 0.0 8.6 Press-Telegram, Long Beach .......................................7.0 4.2 16.9 0.0 28.2 Dothan Eagle..............................................................0.0 4.3 0.0 0.0 4.3 Los Angeles Times......................................................8.5 3.4 6.4 0.2 18.6 Enterprise Ledger........................................................0.0 20.0 0.0 0.0 20.0 Madera Tribune...........................................................0.0 0.0 37.5 0.0 37.5 TimesDaily, Florence...................................................0.0 3.4 0.0 0.0 3.4 Appeal-Democrat, Marysville.......................................4.2 0.0 8.3 0.0 12.5 The Gadsden Times.....................................................0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 Merced Sun-Star.........................................................5.0 -

The NAACP and the Black Freedom Struggle in Baltimore, 1935-1975 Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillm

“A Mean City”: The NAACP and the Black Freedom Struggle in Baltimore, 1935-1975 Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By: Thomas Anthony Gass, M.A. Department of History The Ohio State University 2014 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Hasan Kwame Jeffries, Advisor Dr. Kevin Boyle Dr. Curtis Austin 1 Copyright by Thomas Anthony Gass 2014 2 Abstract “A Mean City”: The NAACP and the Black Freedom Struggle in Baltimore, 1935-1975” traces the history and activities of the Baltimore branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) from its revitalization during the Great Depression to the end of the Black Power Movement. The dissertation examines the NAACP’s efforts to eliminate racial discrimination and segregation in a city and state that was “neither North nor South” while carrying out the national directives of the parent body. In doing so, its ideas, tactics, strategies, and methods influenced the growth of the national civil rights movement. ii Dedication This dissertation is dedicated to the Jackson, Mitchell, and Murphy families and the countless number of African Americans and their white allies throughout Baltimore and Maryland that strove to make “The Free State” live up to its moniker. It is also dedicated to family members who have passed on but left their mark on this work and myself. They are my grandparents, Lucious and Mattie Gass, Barbara Johns Powell, William “Billy” Spencer, and Cynthia L. “Bunny” Jones. This victory is theirs as well. iii Acknowledgements This dissertation has certainly been a long time coming. -

Azaad Liadi Inks Professional Contract with FC Tucson

Georgia Southern University Digital Commons@Georgia Southern Athletics News Athletics 3-10-2020 Azaad Liadi Inks Professional Contract With FC Tucson Georgia Southern University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/athletics-news-online Part of the Higher Education Commons Recommended Citation Georgia Southern University, "Azaad Liadi Inks Professional Contract With FC Tucson" (2020). Athletics News. 2908. https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/athletics-news-online/2908 This article is brought to you for free and open access by the Athletics at Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. It has been accepted for inclusion in Athletics News by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Georgia Southern University Athletics Azaad Liadi Inks Professional Contract With FC Tucson 2019 Sun Belt Newcomer of the Year and second-team All-Sun Belt selection furthers his career in USL League One Men's Soccer Posted: 3/10/2020 3:00:00 PM TUCSON - Georgia Southern men's soccer senior forward Azaad Liadi is furthering his playing career after signing a professional contract with FC Tucson of USL League One. Liadi, the 2019 Sun Belt Conference Newcomer of the Year and a second-team All-Sun Belt selection in his lone season with the Eagles, had been playing with USL League Two's Cincinnati Dutch Lions before inking with FC Tucson on February 12th. "We are all very proud of Azaad and so pleased he has secured a contract with Tucson FC," Georgia Southern Head Men's Soccer Coach John Murphy said. "But he knows the hard work begins now. -

1 DAVID F. FORTE Address

DAVID F. FORTE Address: Cleveland State University Cleveland-Marshall College of Law 1801 Euclid Avenue Cleveland, Ohio 44115 216–687–2342 [email protected] Education: Columbia School of Law, J.D. Certificate of Achievement with Honors, Parker Program in International and Foreign Law Harlan Fiske Stone Scholar University of Toronto, Ph.D. Field: Political Economy Dissertation: The Principles and Policies of Dean Rusk Junior Fellow, Massey College University of Manchester, England, M.A. (Econ.) Field: International Affairs Dissertation: The Response of Soviet Foreign Policy to the Common Market Harvard College, A.B. Field: Government Honors Thesis: The Theory of International Relations of Henry Cabot Lodge Bar Memberships: Supreme Court of Ohio U.S. District Court, Northern District of Ohio U.S. Court of Appeals, Sixth Circuit U.S. Supreme Court Professional Experience 1 University of Warsaw Distinguished Fulbright Chair, Faculty of Law and Administration, 2019 Courses: The United States Supreme Court, The Idea of Justice Princeton University Garwood Visiting Professor, Department of Politics, 2016-2017 Courses: The Successful President, The Idea and the Reality of Justice Visiting Fellow, The James Madison Program in American Ideals and Institutions, 2016-2017 Fellow, Wilson College Cleveland-Marshall College of Law Professor of Law, 1981–present Charles R. Emrick. Jr.—Calfee, Halter, & Griswold Endowed Professor of Law, 2004-2007 Associate Professor of Law, 1976–81 Courses: Constitutional Law, International Law, Jurisprudence, Islamic Law, International Law and Human Rights, Theories of Justice, First Amendment Rights. Associate Dean for Academic Affairs, 1986–88 Responsible for coordination and implementation of the academic program, faculty development, curricular reform, adjunct faculty hiring. -

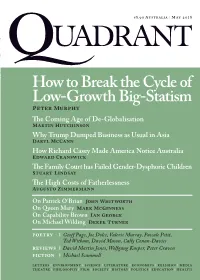

Howtobreak the Cycle of Low-Growthbig-Statism

Q ua dr a nt $8.90 Australia I M ay 2018 I V ol.62 N o.5 M ay 2018 How to Break the Cycle of Low-GrowthPeter Murphy Big-Statism The Coming Age of De-Globalisation Martin Hutchinson Why Trump Dumped Business as Usual in Asia Daryl McCann How Richard Casey Made America Notice Australia Edward Cranswick The Family Court has Failed Gender-Dysphoric Children Stuart Lindsay The High Costs of Fatherlessness Augusto Zimmermann On Patrick O’Brian John Whitworth On Queen Mary Mark McGinness On Capability Brown Ian George On Michael Wilding Derek Turner Poetry I Geoff Page, Joe Dolce, Valerie Murray, Pascale Petit, Ted Witham, David Mason, Cally Conan-Davies Reviews I David Martin Jones, Wolfgang Kasper, Peter Craven Fiction I Michael Scammell Letters I Environment I Science I Literature I Economics I Religion I Media Theatre I Philosophy I film I Society I History I Politics I Education I Health SpeCIal New SubSCrIber offer renodesign.com.aur33011 Subscribe to Quadrant and Q ua dr a nt Policy for only $104 for one year! $8.90 Australia I M arch 2012 I Vol.56 No3 M arch 2012 The Threat to Democracy Quadrant is one of Australia’ Jfromohn O’Sullivan, Global Patrick MGovernancecCauley The Fictive World of Rajendra Pachauri and is published ten times a year.s leading intellectual magazines, Tony Thomas Pax Americana and the Prospect of US Decline Keith Windschuttle Why Africa Still Has a Slave Trade Roger Sandall Policy is the only Australian quarterly magazine that explores Freedom of Expression in a World of Vanishing Boundaries Nicholas Hasluck the world of ideas and policy from a classical liberal perspective.