The Chronicles of America Series Allen Johnson Editor

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Works of Washington Irving

ALFRED SANTEU KNICKERBOCKER S HISTORY OF NEW YORK WHEN THE RIVAL HEROES CAME FACE TO FACE. ffulton lEMtton THE WORKS OF WASHINGTON IRVING KNICKERBOCKER S HISTORY OF NEW YORK NEW YORK THE CENTURY CO. 1910 Stack Annex CONTENTS PAGE THE AUTHOR S APOLOGY ................ i ACCOUNT OF THE AUTHOR ............... 5 To THE PUBLIC .................... 15 BOOK I CONTAINING DIVERS INGENIOUS THEORIES AND PHILOSOPHIC SPECULATIONS, CONCERNING THE CREATION AND POPULA TION OF THE WORLD, AS CONNECTED WITH THE HISTORY OF NEW YORK CHAP. I. Description of the World ............ 21 II. or Creation of the World with a CHAP. Cosmogony, ; mul titude of excellent theories, by which the creation of a world is shown to be no such difficult matter as common folk would imagine ....................... 27 CHAP. III. How that famous navigator, Noah, was shamefully nicknamed; and how he committed an unpardonable over sight in not having four sons. With the great trouble of philosophers caused thereby, and the discovery of America . 35 CHAP. IV. Showing the great difficulty philosophers have had in peopling America and how the Aborigines came to be begotten by accident to the great relief and satisfaction of the Author ..................... 41 CHAP. V. In which the Author puts a mighty question to the rout, by the assistance of the Man in the Moon which not only delivers thousands of people from great embarrassment, but likewise concludes this introductory book ...... 47 BOOK II TREATING OF THE FIRST SETTLEMENT OF THE PROVINCE OF NIEUW-NEDERLANDTS CHAP. I. In which are contained divers reasons why a man should not write in a hurry Also of Master Hendrick Hudson, his discovery of a strange country and how he was vi CONTENTS PAGE magnificently rewarded by the munificence of their High Mightinesses 63 CHAP. -

Social Studies Chapter 4, Lesson 1 Study Guide Name______Date______

Social Studies Chapter 4, Lesson 1 Study Guide Name_______________ Date___________ Key terms: Write the definition of each key term for Lesson 1. 1. Explorer-a person who travels to unfamiliar places in order to learn about them 2. Northwest Passage- a water route through North America to Asia (does not exist) 3. Trading Post-a store in a sparsely settled area where local people can barter (trade) products for goods 4. Colony-a place ruled by another country 5. Manufactured Goods- things that are manmade such as metal axes and cooking pots, and weapons Directions: Use the method, Who? What did he/she do? When? Where? and So What? to give the importance of each of the following people. The first has been done for you! 6. Henry Hudson- (Who?) Henry Hudson was an explorer (What did he/she do?) who was searching for a Northwest Passage (When?) in 1609 (Where) when he came upon the Delaware Bay. (So What?) He reported his findings to the rulers of European countries which caused them to send explorers to claim the land for their own. 7. Cornelius Hendrickson- was a Dutch Explorer from the Netherlands who came to the Delaware Bay in 1616. The Dutch set up two trading posts to trade with the Native Americans for beaver furs 8. Peter Minuit- A Dutch man hired by Sweden. In 1636 he bought land from the Native Americans to set up a colony for the Swedish named New Sweden. It is located near where Wilmington, DE is today. Swedish colonists and soldiers build Fort Christina, showing other countries that Sweden had some military power in the New World 9. -

The Archaeology of 17Th-Century New Netherland Since1985: an Update Paul R

Northeast Historical Archaeology Volume 34 From the Netherlands to New Netherland: The Archaeology of the Dutch in the Old and New Article 6 Worlds 2005 The Archaeology of 17th-Century New Netherland Since1985: An Update Paul R. Huey Follow this and additional works at: http://orb.binghamton.edu/neha Part of the Archaeological Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Huey, Paul R. (2005) "The Archaeology of 17th-Century New Netherland Since1985: An Update," Northeast Historical Archaeology: Vol. 34 34, Article 6. https://doi.org/10.22191/neha/vol34/iss1/6 Available at: http://orb.binghamton.edu/neha/vol34/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by The Open Repository @ Binghamton (The ORB). It has been accepted for inclusion in Northeast Historical Archaeology by an authorized editor of The Open Repository @ Binghamton (The ORB). For more information, please contact [email protected]. Northeast Historical Archaeology/Vol. 34,2005 95 The Archaeology of 17th-Century New Netherland Since 1985: An Update Paul R. Huey . In 1985, a number of goals and research questions were proposed in relation to the archaeology of' pre-1664 sites in the Dutch colony of New Netherland. Significant Dutch sites were subsequently ~xcavated in Albany, Kingston, and other places from 1986 through 1988, while a series of useful publications con tinued to be produced after 1988. Excavations at historic period Indian sites also continued after 1988 . Excavations in 17th-century sites from Maine to Maryland have revealed extensive trade contacts with New Netherland and the Dutch, while the Jamestown excavations have indicated the influence of the Dutch !n the early history of Virginia. -

Washington Irving's Use of Historical Sources in the Knickerbocker History of New York

WASHINGTON IRVING’S USE OF HISTORICAL SOURCES IN THE KNICKERBOCKER. HISTORY OF NEW YORK Thesis for the Degree of M. A. MICHIGAN STATE UNIVERSITY DONNA ROSE CASELLA KERN 1977 IIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIII IIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIII 3129301591 2649 WASHINGTON IRVING'S USE OF HISTORICAL SOURCES IN THE KNICKERBOCKER HISTORY OF NEW YORK By Donna Rose Casella Kern A THESIS Submitted to Michigan State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Department of English 1977 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION . CHAPTER I A Survey of Criticism . CHAPTER II Inspiration and Initial Sources . 15 CHAPTER III Irving's Major Sources William Smith Jr. 22 CHAPTER IV Two Valuable Sources: Charlevoix and Hazard . 33 CHAPTER V Other Sources 0 o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o 0 Al CONCLUSION 0 O C O O O O O O O O O O O 0 O O O O O 0 53 APPENDIX A Samuel Mitchell's A Pigture 9: New York and Washington Irving's The Knickerbocker Histgrx of New York 0 o o o o o o o o o o o o o c o o o o 0 56 APPENDIX B The Legend of St. Nicholas . 58 APPENDIX C The Controversial Dates . 61 APPENDIX D The B00k'S Topical Satire 0 o o o o o o o o o o 0 6A APPENDIX E Hell Gate 0 0.0 o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o 0 66 APPENDIX F Some Minor Sources . -

Council Minutes 1655-1656

Council Minutes 1655-1656 New Netherland Documents Series Volume VI ^:OVA.BUfi I C ^ u e W « ^ [ Adriaen van der Donck’s Map of New Netherland, 1656 Courtesy of the New York State Library; photo by Dietrich C. Gehring Council Minutes 1655-1656 ❖ Translated and Edited by CHARLES T. GEHRING SJQJ SYRACUSE UNIVERSITY PRESS Copyright © 1995 by The Holland Society of New York ALL RIGHTS RESERVED First Edition, 1995 95 96 97 98 99 6 5 4 3 21 The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements o f American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z 39.48-1984.@™ Produced with the support of The Holland Society o f New York and the New Netherland Project of the New York State Library The preparation of this volume was made possibl&in part by a grant from the Division of Research Programs of the National Endowment for the Humanities, an independent federal agency. This book is published with the assistance o f a grant from the John Ben Snow Foundation. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data New Netherland. Council. Council minutes, 1655-1656 / translated and edited by Charles T. Gehring. — lsted. p. cm. — (New Netherland documents series ; vol. 6) Includes index. ISBN 0-8156-2646-0 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. New York (State)— Politics and government—To 1775— Sources. 2. New York (State)— History—Colonial period, ca. 1600-1775— Sources. 3. New York (State)— Genealogy. 4. Dutch—New York (State)— History— 17th century—Sources. 5. Dutch Americans—New York (State)— Genealogy. -

Going on the Account: Examining Golden Age Pirates As a Distinct

GOING ON THE ACCOUNT: EXAMINING GOLDEN AGE PIRATES AS A DISTINCT CULTURE THROUGH ARTIFACT PATTERNING by Courtney E. Page December, 2014 Director of Thesis: Dr. Charles R. Ewen Major Department: Anthropology Pirates of the Golden Age (1650-1726) have become the stuff of legend. The way they looked and acted has been variously recorded through the centuries, slowly morphing them into the pirates of today’s fiction. Yet, many of the behaviors that create these images do not preserve in the archaeological environment and are just not good indicators of a pirate. Piracy is an illegal act and as a physical activity, does not survive directly in the archaeological record, making it difficult to study pirates as a distinct maritime culture. This thesis examines the use of artifact patterning to illuminate behavioral differences between pirates and other sailors. A framework for a model reflecting the patterns of artifacts found on pirate shipwrecks is presented. Artifacts from two early eighteenth century British pirate wrecks, Queen Anne’s Revenge (1718) and Whydah (1717) were categorized into five groups reflecting behavior onboard the ship, and frequencies for each group within each assemblage were obtained. The same was done for a British Naval vessel, HMS Invincible (1758), and a merchant vessel, the slaver Henrietta Marie (1699) for comparative purposes. There are not enough data at this time to predict a “pirate pattern” for identifying pirates archaeologically, and many uncontrollable factors negatively impact the data that are available, making a study of artifact frequencies difficult. This research does, however, help to reveal avenues of further study for describing this intriguing sub-culture. -

School Election

Glasgow runners prepare for Hands Across America/lh Uf.\R R Newark's 'boom boom girls'/8a Tonsina is a winner/lb Vol. 75, ~o. 48 May7,1986 School election by john Saturday Voters will select McWhorter two board members he prom. Webster's Dic For coverage of views of tionary defines the Christina Board of Education can T prom as a formal didates as expressed during Mon dance given by a high day night's League of Women school or college class, but Voters forum, see page 4a. to local high school students the prom is much more than Christina School District "a formal dance." residents will go to the polls To some, the prom is a Saturday, May 10 to select two time to dress their best. To school board members. others it is an opportunity to show the one they love that In District D, the northeastern they really care. But most Newark section of Christina, in of all, the prom is the final cumbent Alfred I. Daniel of Red celebration before gradua Mill Farms is being challenged tion and all of the respon by Charles " Ed" Hockersmith of sibilities that follow. the same development. The win For a period, the prom ner will gain a five-year term. had fallen out of favor with In District G, the school many young people. In the district's southeastern suburban late 1960s and early 1970s, it area, Dona B. Pl'ice of Eagle wasn't "cool" to attend the Glen is squaring off against prom and bynot attending Suzanne S. -

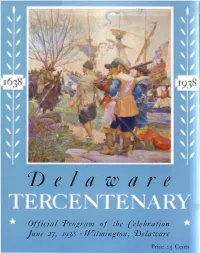

Delaware Tercentenary Program

Vela ware Official Program., of the Celebration June 27, I9J8 ·Wilmington, 'Delaware Price 25 Cents FORT CHRISTINA H.M. CHRISTINA, Queen of Sweden (r6J'l-l 654) during H.M. GusTAvus A oo LPH U s , King of Sweden (161 '· whose reign New Sweden was founded. I 632) through whose support New Sweden becan1e a possibility. l DEcEMBER 1637, the Swedish Expedi tion, under Peter Minuit, sailed from Sweden in the ship, "Kalmar Nyckel" and the yacht,"Fogel Grip," and finally reached the "Rocks" in March r6J8. Here Minui t made a treaty with the Indians and, with a salute of two cannons, claimed for Sweden all that land from the Christina River down to Bombay Hook. Wt�forl(g� ?t�dfantt� �fnur }llttttbetaCONTRACTET gnga(n�cat�ct S�bre �mpagnict �tbf J(onuugart;rctj ewcrfg�c. 6rdlc iam·om �it�dm &\jffdin�. £)�uu 4/ft6tt 9?tl)trfdnb(rc �prdfct �fau p.S6�Mnfl.al 2ft' ~ £ BEGINNINGS of the establishment of New }:RICO SCHRODERO. L S~eden rnay be traced back to the efforts of one William Usselinx, a native of Antwerp, who interested King Gustavus Adolphus in the enter prise. At the right is reproduced the cover of the contract and prospectus which was used to interest The Cover investors in the venture. Here is reproduced the famous painting by Stanley M. Arthurs, Esq., ofthe landing ofthe .firstSwedish expedi tion at the "Roclcs." The painting is owned by Joseph S. Wilson, Esq. GusTAF V ' K.lng • of S weden , d u r .1 n g . w h ose reign, In I9J8 , t h e ter- centenary of · the found·lng of N ew Sweden IS celebrated. -

Chronology of Colonial Swedes on the Delaware 1638-1713 by Dr

Chronology of Colonial Swedes on the Delaware 1638-1713 by Dr. Peter Stebbins Craig Fellow, American Society of Genealogists Fellow, Genealogical Society of Pennsylvania Historian, Swedish Colonial Society originally published in Swedish Colonial News, Volume 2, Number 5 (Fall 2001) Although it is commonly known that the Swedes were the first white settlers to successfully colonize the Delaware Valley in 1638, many historians overlook the continuing presence of the Delaware Swedes throughout the colonial period. Some highlights covering the first 75 years (1638-1713) are shown below: New Sweden Era, 1638-1655 1638 - After a 4-month voyage from Gothenburg, Kalmar Nyckel arrives in the Delaware in March. Captain Peter Minuit purchases land on west bank from the Schuylkill River to Bombay Hook, builds Fort Christina at present Wilmington and leaves 24 men, under the command of Lt. Måns Kling, to man the fort and trade with Indians. Kalmar Nyckel returns safely to Sweden, but Minuit dies on return trip in a hurricane in the Caribbean. 1639 - Fogel Grip, which accompanied Kalmal Nyckel, brings a 25th man from St. Kitts, a slave from Angola known as Anthony Swartz. 1640 - Kalmar Nyckel, on its second voyage, brings the first families to New Sweden, including those of Sven Gunnarsson and Lars Svensson. Other new settlers include Peter Rambo, Anders Bonde, Måns Andersson, Johan Schaggen, Anders Dalbo and Dr. Timen Stiddem. Lt. Peter Hollander Ridder, who succeeds Kling as new commanding officer, purchases more land from Indians between Schuylkill and the Falls of the Delaware. 1641 - Kalmar Nyckel, joined by the Charitas, brings 64 men to New Sweden, including the families of Måns Lom, Olof Stille, Christopher Rettel, Hans Månsson, Olof Thorsson and Eskil Larsson. -

Peter Stuyvesant's Leadership of New Netherland

Peter Stuyvesant’s leadership of New Netherland University of Oulu Department of History Bachelor’s dissertation 6.5.2020 Henrik Lodewijks 2 Table of contents Introduction .................................................................................................................. 3 1. Peter Stuyvesant’s rise to power and militarism ................................................... 9 1.1 Peter Stuyvesant lands in North America .............................................................. 9 1.2 Peter Stuyvesant’s militaristic views ................................................................... 13 2. Peter Stuyvesant’s time in office and relation with the settlers. ......................... 17 2.1The extent of Peter Stuyvesant’s power ................................................................ 17 2.2Peter Stuyvesant and the settlers of New Amsterdam .......................................... 19 Conclusion ................................................................................................................. 23 Sources ....................................................................................................................... 25 3 Introduction Research on the colony of New Netherland is quite a new phenomenon. When looking into the studies made of the subject, most of them are quite new and have been published in the late 20th century or 21st century. The studies have been made mostly by Dutch researchers or Dutch American researchers on the east coast of the USA. The cultural heritage of the Dutch -

The Jolly Jack Tar and Eighteenth-Century British Masculinity

CARNEGIE MELLON UNIVERSITY Three Sheets to the Wind: The Jolly Jack Tar and Eighteenth-Century British Masculinity by Juliann Elizabeth Reineke A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2018 i Abstract My dissertation traces the development of the Jolly Jack Tar, a widespread image of the common British sailor, beginning with the formal establishment of Royal Navy in 1660 and ending in 1817 with the publication of Jane Austen’s Persuasion, a novel devoted to presenting a new model of the professional seaman. I also analyze Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe (1719), Charles Johnson’s A General History of the Robberies and Murders of the Most Notorious Pyrates (1724), Tobias Smollett’s Roderick Random (1748), and Olaudah Equiano’s The Interesting Narrative (1789) in conjunction with ephemeral cultural artifacts like songs, cartoons, newspapers, and miscellany to fill in the variable, uneven history of the novelistic Jack Tar over the course of the long eighteenth century. My analysis seeks to answer the following questions: How do fictionalized accounts of sailors (like those found in novels) reflect, challenge, or reinforce the portrayal of sailors in other cultural texts, like songs or plays? How does print culture inflect the construction of Jack Tar, particularly regarding the figure’s connection to Britain and an emergent national identity? How do literary and cultural texts represent seamen’s complicated relationship to the home and the family, particularly when seamen were, by the nature of their profession, typically far from Britain? To answer these questions, I bring together print history, performance studies, post-colonial studies, maritime history, and disability studies. -

Dutch Exploration and Settlement in North America

Name__________________________________________ Date___________ Mankes, Period_____ Dutch Exploration and Settlement in North America Just like the French, the Dutch also wanted to look for new ways to reach the riches of Asia. Dutch people are from The Netherlands in Europe. In 1609, the English explorer Henry Hudson sailed for the Dutch. His ship, the Half Moon, entered present-day New York harbor. Hudson continued to sail some 150 miles up the river that today bears his name. Even though he failed to find a northwest passage, he did map and explore this area. We will watch a brief video about Dutch New York. Answer the questions below based on information from the video. https://www.thirteen.org/dutchny/video/video-dutch-new-york/ (stop the video at 11:40) 1. What would Manhattan have looked like when Hudson landed in 1609? (Describe the land, water, animals, landscape) 2. Describe relations between the early Dutch settlers and Native Americans. 3. Write one more interesting fact you learn from the video. In 1626, Peter Minuit led a group of Dutch settlers to the mouth of the Hudson River. There, he bought Manhattan Island from local Indians. Minuit called the settlement New Amsterdam. Other colonists settled father up the Hudson River. The entire colony was known as New Netherland (later becomes New York) New Amsterdam grew into a busy trading port. The Dutch welcomed people of many nations and religions to their colony. “On the island of Manhattan…there may well be four or five hundred men of different…nations…men of eighteen different languages…” -Father Isaac Jogues, 1609 After reading Father Jogues quote, why might someone consider New Amsterdam as a “multicultural” settlement? ______________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________________________ The Dutch and French soon became rivals in the fur trade.