Notes on Field Identification, Vocalisation, Status, and Distribution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Band 49 • Heft 2 • Mai 2011

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Hochschulschriftenserver - Universität Frankfurt am Main Band 49 • Heft 2 • Mai 2011 Deutsche Ornithologen-Gesellschaft e.V. Institut für Vogelforschung Vogelwarte Hiddensee Max-Planck-Institut für Ornithologie „Vogelwarte Helgoland“ und Vogelwarte Radolfzell Beringungszentrale Hiddensee Die „Vogelwarte“ ist offen für wissenschaftliche Beiträge und Mitteilungen aus allen Bereichen der Orni- tho logie, einschließlich Avifaunistik und Beringungs wesen. Zusätzlich zu Originalarbeiten werden Kurz- fassungen von Dissertationen, Master- und Diplomarbeiten aus dem Be reich der Vogelkunde, Nach richten und Terminhinweise, Meldungen aus den Berin gungszentralen und Medienrezensionen publiziert. Daneben ist die „Vogelwarte“ offizielles Organ der Deutschen Ornithologen-Gesellschaft und veröffentlicht alle entsprechenden Berichte und Mitteilungen ihrer Gesellschaft. Herausgeber: Die Zeitschrift wird gemein sam herausgegeben von der Deutschen Ornithologen-Gesellschaft, dem Institut für Vogelforschung „Vogelwarte Helgoland“, der Vogelwarte Radolfzell am Max-Planck-Institut für Ornithologie, der Vogelwarte Hiddensee und der Beringungszentrale Hiddensee. Die Schriftleitung liegt bei einem Team von vier Schriftleitern, die von den Herausgebern benannt werden. Die „Vogelwarte“ ist die Fortsetzung der Zeitschriften „Der Vogelzug“ (1930 – 1943) und „Die Vogelwarte“ (1948 – 2004). Redaktion / Schriftleitung: DO-G-Geschäftsstelle: Manuskripteingang: Dr. Wolfgang Fiedler, Vogelwarte Radolf- Karl Falk, c/o Institut für Vogelfor- zell am Max-Planck-Institut für Ornithologie, Schlossallee 2, schung, An der Vogelwarte 21, 26386 D-78315 Radolfzell (Tel. 07732/1501-60, Fax. 07732/1501-69, Wilhelmshaven (Tel. 0176/78114479, [email protected]) Fax. 04421/9689-55, Dr. Ommo Hüppop, Institut für Vogelforschung „Vogelwarte Hel- [email protected] http://www.do-g.de) goland“, Inselstation Helgoland, Postfach 1220, D-27494 Helgo- Alle Mitteilungen und Wünsche, welche die Deutsche Ornitho- land (Tel. -

BORNEO: Bristleheads, Broadbills, Barbets, Bulbuls, Bee-Eaters, Babblers, and a Whole Lot More

BORNEO: Bristleheads, Broadbills, Barbets, Bulbuls, Bee-eaters, Babblers, and a whole lot more A Tropical Birding Set Departure July 1-16, 2018 Guide: Ken Behrens All photos by Ken Behrens TOUR SUMMARY Borneo lies in one of the biologically richest areas on Earth – the Asian equivalent of Costa Rica or Ecuador. It holds many widespread Asian birds, plus a diverse set of birds that are restricted to the Sunda region (southern Thailand, peninsular Malaysia, Sumatra, Java, and Borneo), and dozens of its own endemic birds and mammals. For family listing birders, the Bornean Bristlehead, which makes up its own family, and is endemic to the island, is the top target. For most other visitors, Orangutan, the only great ape found in Asia, is the creature that they most want to see. But those two species just hint at the wonders held by this mysterious island, which is rich in bulbuls, babblers, treeshrews, squirrels, kingfishers, hornbills, pittas, and much more. Although there has been rampant environmental destruction on Borneo, mainly due to the creation of oil palm plantations, there are still extensive forested areas left, and the Malaysian state of Sabah, at the northern end of the island, seems to be trying hard to preserve its biological heritage. Ecotourism is a big part of this conservation effort, and Sabah has developed an excellent tourist infrastructure, with comfortable lodges, efficient transport companies, many protected areas, and decent roads and airports. So with good infrastructure, and remarkable biological diversity, including many marquee species like Orangutan, several pittas and a whole Borneo: Bristleheads and Broadbills July 1-16, 2018 range of hornbills, Sabah stands out as one of the most attractive destinations on Earth for a travelling birder or naturalist. -

Historic Changes in Species Composition for a Globally Unique Bird Community Swen C

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Historic changes in species composition for a globally unique bird community Swen C. Renner 1,2* & Paul J. J. Bates 2,3 Signifcant uncertainties remain of how global change impacts on species richness, relative abundance and species composition. Recently, a discussion emerged on the importance of detecting and understanding long-term fuctuations in species composition and relative abundance and whether deterministic or non-deterministic factors can explain any temporal change. However, currently, one of the main impediments to providing answers to these questions is the relatively short time series of species diversity datasets. Many datasets are limited to 2 years and it is rare for a few decades of data to be available. In addition, long-term data typically has standardization issues from the past and/or the methods are not comparable. We address several of these uncertainties by investigating bird diversity in a globally important mountain ecosystem of the Hkakabo Razi Landscape in northern Myanmar. The study compares bird communities in two periods (pre-1940: 1900–1939 vs. post-2000: 2001–2006). Land-cover classes have been included to provide understanding of their potential role as drivers. While species richness did not change, species composition and relative abundance difered, indicating a signifcant species turn over and hence temporal change. Only 19.2% of bird species occurred during both periods. Land-cover model predictors explained part of the species richness variability but not relative abundance nor species composition changes. The temporal change is likely caused by minimal methodological diferences and partially by land-cover. Species richness, relative abundance and species composition are dynamic phenomena and vary in space and over time1,2. -

MORPHOLOGICAL and ECOLOGICAL EVOLUTION in OLD and NEW WORLD FLYCATCHERS a Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the College O

MORPHOLOGICAL AND ECOLOGICAL EVOLUTION IN OLD AND NEW WORLD FLYCATCHERS A dissertation presented to the faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Clay E. Corbin August 2002 This dissertation entitled MORPHOLOGICAL AND ECOLOGICAL EVOLUTION IN OLD AND NEW WORLD FLYCATCHERS BY CLAY E. CORBIN has been approved for the Department of Biological Sciences and the College of Arts and Sciences by Donald B. Miles Associate Professor, Department of Biological Sciences Leslie A. Flemming Dean, College of Arts and Sciences CORBIN, C. E. Ph.D. August 2002. Biological Sciences. Morphological and Ecological Evolution in Old and New World Flycatchers (215pp.) Director of Dissertation: Donald B. Miles In both the Old and New Worlds, independent clades of sit-and-wait insectivorous birds have evolved. These independent radiations provide an excellent opportunity to test for convergent relationships between morphology and ecology at different ecological and phylogenetic levels. First, I test whether there is a significant adaptive relationship between ecology and morphology in North American and Southern African flycatcher communities. Second, using morphological traits and observations on foraging behavior, I test whether ecomorphological relationships are dependent upon locality. Third, using multivariate discrimination and cluster analysis on a morphological data set of five flycatcher clades, I address whether there is broad scale ecomorphological convergence among flycatcher clades and if morphology predicts a course measure of habitat preference. Finally, I test whether there is a common morphological axis of diversification and whether relative age of origin corresponds to the morphological variation exhibited by elaenia and tody-tyrant lineages. -

Borneo July 11–29, 2019

BORNEO JULY 11–29, 2019 Extreme close views on our tour of this fantastic Black-and-yellow Broadbill (Photo M. Valkenburg) LEADER: MACHIEL VALKENBURG LIST COMPILED BY: MACHIEL VALKENBURG VICTOR EMANUEL NATURE TOURS, INC. 2525 WALLINGWOOD DRIVE, SUITE 1003 AUSTIN, TEXAS 78746 WWW.VENTBIRD.COM BY MACHIEL VALKENBURG Borneo, Borneo, magical Borneo! This was my fourth trip to Sabah and, as always, it was a pleasure to bird the third largest island of the world. As in many rainforests, the birding can be tricky, and sometimes it means standing and looking at bushes within distance of a faint call from the desired jewel. Sometimes it took quite some patience to find the birds, but we did very well and were lucky with many good views of the more difficult birds of the island. Our group flew in to Kota Kinabalu, where our journey began. During the first part of the tour we focused on the endemic-rich Kinabalu mountain, which we birded from the conveniently located Hill Lodge right at the park entrance. After birding the cool mountains, we headed with pleasure for the tropical Sabah lowlands, with Sepilok as our first stop followed by the Kinabatangan River and Danum Valley Rainforest. The Kinabatangan River is a peat swamp forest holding some very special fauna and flora. Tall dipterocarps dominate the forests of Sepilok and Danum; we did very well in finding the best birds on offer in all places visited. We had 30-minute walkaway views of the superb Whitehead’s Broadbill (photo M.Valkenburg) In the Kinabalu park we walked some trails, but mostly we birded and walked easily along the main road through this gorgeous forest filled with epiphytes and giant tree-ferns. -

A Short Survey of the Meratus Mountains, South Kalimantan Province, Indonesia: Two Undescribed Avian Species Discovered

BirdingASIA 26 (2016): 107–113 107 LITTLEKNOWN AREA A short survey of the Meratus Mountains, South Kalimantan province, Indonesia: two undescribed avian species discovered J. A. EATON, S. L. MITCHELL, C. NAVARIO GONZALEZ BOCOS & F. E. RHEINDT Introduction of the montane part of Indonesia’s Kalimantan The avian biodiversity and endemism of Borneo provinces has seldom been visited (Brickle et al. is impressive, with some 50 endemic species 2009). One of the least-known areas and probably described from the island under earlier taxonomic the most isolated mountain range (Davison 1997) arrangements (e.g. Myers 2009), and up to twice are the Meratus Mountains, South Kalimantan as many under the recently proposed taxonomic province (Plates 1 & 2), a 140 km long north–south arrangements of Eaton et al. (2016). Many of arc of uplands clothed with about 2,460 km² of these are montane specialists, with around 27 submontane and montane forest, rising to the species endemic to Borneo’s highlands. Although 1,892 m summit of Gn Besar (several other peaks the mountains of the Malaysian states, Sabah exceed 1,600 m). Today, much of the range is and Sarawak, are relatively well-explored, much unprotected except for parts of the southern Plates 1 & 2. Views across the Meratus Mountain range, South Kalimantan province, Kalimantan, Indonesia, showing extensive forest cover, July 2016. CARLOS NAVARIO BOCOS CARLOS NAVARIO BOCOS 108 A short survey of the Meratus Mountains, South Kalimantan, Indonesia: two undescribed avian species discovered end that lie in the Pleihari Martapura Wildlife (2.718°S 115.599°E). Some surveys were curtailed Reserve (Holmes & Burton 1987). -

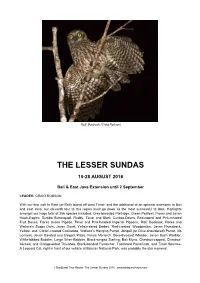

The Lesser Sundas

‘Roti’ Boobook (Craig Robson) THE LESSER SUNDAS 10-28 AUGUST 2016 Bali & East Java Extension until 2 September LEADER: CRAIG ROBSON With our first visit to Rote (or Roti) Island off west Timor, and the additional of an optional extension to Bali and east Java, our eleventh tour to this region must go down as the most successful to date. Highlights amongst our huge total of 356 species included: Grey-breasted Partridge, Green Peafowl, Flores and Javan Hawk-Eagles, Sumba Buttonquail, Ruddy, Timor and Black Cuckoo-Doves, Red-naped and Pink-headed Fruit Doves, Flores Green Pigeon, Timor and Pink-headed Imperial Pigeons, ‘Roti’ Boobook, Flores and Wallace's Scops Owls, Javan Owlet, Yellow-eared Barbet, ‘Red-crested’ Woodpecker, Javan Flameback, Yellow- and ‘Citron’-crested Cockatoos, Wallace’s Hanging Parrot, Jonquil (or Olive-shouldered) Parrot, Iris Lorikeet, Javan Banded and Elegant Pittas, Flores Monarch, Bare-throated Whistler, Javan Bush Warbler, White-bibbed Babbler, Large Wren-Babbler, Black-winged Starling, Bali Myna, Chestnut-capped, Chestnut- backed, and Orange-sided Thrushes, Black-banded Flycatcher, Tricolored Parrotfinch, and Timor Sparrow. A Leopard Cat, right in front of our vehicle at Baluran National Park, was probably the star mammal. ! ! 1 BirdQuest Tour Report: The Lesser Sundas 2016 www.birdquest-tours.com We all assembled at the Airport in Denpasar, Bali and checked-in for our relatively short flight to Waingapu, the main town on the island of Sumba. On arrival we were whisked away to our newly built hotel, and arrived just in time for lunch. By the early afternoon we were already beginning our explorations with a visit to the coastline north-west of town in the Londa Liru Beach area. -

![1 §4-71-6.5 List of Restricted Animals [ ] Part A: For](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5559/1-%C2%A74-71-6-5-list-of-restricted-animals-part-a-for-2725559.webp)

1 §4-71-6.5 List of Restricted Animals [ ] Part A: For

§4-71-6.5 LIST OF RESTRICTED ANIMALS [ ] PART A: FOR RESEARCH AND EXHIBITION SCIENTIFIC NAME COMMON NAME INVERTEBRATES PHYLUM Annelida CLASS Hirudinea ORDER Gnathobdellida FAMILY Hirudinidae Hirudo medicinalis leech, medicinal ORDER Rhynchobdellae FAMILY Glossiphoniidae Helobdella triserialis leech, small snail CLASS Oligochaeta ORDER Haplotaxida FAMILY Euchytraeidae Enchytraeidae (all species in worm, white family) FAMILY Eudrilidae Helodrilus foetidus earthworm FAMILY Lumbricidae Lumbricus terrestris earthworm Allophora (all species in genus) earthworm CLASS Polychaeta ORDER Phyllodocida FAMILY Nereidae Nereis japonica lugworm PHYLUM Arthropoda CLASS Arachnida ORDER Acari FAMILY Phytoseiidae 1 RESTRICTED ANIMAL LIST (Part A) §4-71-6.5 SCIENTIFIC NAME COMMON NAME Iphiseius degenerans predator, spider mite Mesoseiulus longipes predator, spider mite Mesoseiulus macropilis predator, spider mite Neoseiulus californicus predator, spider mite Neoseiulus longispinosus predator, spider mite Typhlodromus occidentalis mite, western predatory FAMILY Tetranychidae Tetranychus lintearius biocontrol agent, gorse CLASS Crustacea ORDER Amphipoda FAMILY Hyalidae Parhyale hawaiensis amphipod, marine ORDER Anomura FAMILY Porcellanidae Petrolisthes cabrolloi crab, porcelain Petrolisthes cinctipes crab, porcelain Petrolisthes elongatus crab, porcelain Petrolisthes eriomerus crab, porcelain Petrolisthes gracilis crab, porcelain Petrolisthes granulosus crab, porcelain Petrolisthes japonicus crab, porcelain Petrolisthes laevigatus crab, porcelain Petrolisthes -

Voelker and Spellman.Pdf

MOLECULAR PHYLOGENETICS AND EVOLUTION Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 30 (2004) 386–394 www.elsevier.com/locate/ympev Nuclear and mitochondrial DNA evidence of polyphyly in the avian superfamily Muscicapoidea Gary Voelker* and Garth M. Spellman Barrick Museum of Natural History, Box 454012, University of Nevada Las Vegas, 4505 Maryland Parkway, Las Vegas, NV 89154, USA Received 26 November 2002; revised 7 May 2003 Abstract Nucleotide sequences of the nuclear c-mos gene and the mitochondrial cytochrome b and ND2 genes were used to assess the monophyly of Sibley and MonroeÕs [Distribution and Taxonomy of Birds of the World, Yale University Press, New Haven, 1990] Muscicapoidea superfamily. The relationships and monophyly of major lineages within the superfamily, as well as genera mem- bership in major lineages was also assessed. Analyses suggest that Bombycillidae is not a part of Muscicapoidea, and there is strongly supported evidence to suggest that Turdinae is not part of the Muscicapidae, but is instead sister to a Sturnidae + Cinclidae clade. This clade is in turn sister to Muscicapidae (Muscicapini + Saxicolini). Of the 49 Turdinae and Muscicapidae genera that we included in our analyses, 10 (20%) are shown to be misclassified to subfamily or tribe. Our results place one current Saxicolini genus in Turdinae, two Saxicolini genera in Muscicapini, and five Turdinae and two Muscicapini genera in Saxicolini; these relationships are supported with 100% Bayesian support. Our analyses suggest that c-mos was only marginally useful in resolving these ‘‘deep’’ phylogenetic relationships. Ó 2003 Published by Elsevier Science (USA). Keywords: Bombycillidae; Cinclidae; Molecular systematics; Muscicapidae; Muscicapoidea; Sibley and Ahlquist; Sturnidae 1. -

Two New Genera of Songbirds Represent Endemic Radiations from the Shola Sky Islands of the Western Ghats, India

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Biology: Faculty Publications and Other Works Faculty Publications 1-23-2017 Two New Genera of Songbirds Represent Endemic Radiations from the Shola Sky Islands of the Western Ghats, India Sushma Reddy Loyola University Chicago, [email protected] V. V. Robin National Centre for Biological Sciences, TIFR C. K. Vishnudas National Centre for Biological Sciences, TIFR Pooja Gupta National Centre for Biological Sciences, TIFR Frank E. Rheindt National University of Singapore SeeFollow next this page and for additional additional works authors at: https:/ /ecommons.luc.edu/biology_facpubs Part of the Biology Commons Recommended Citation Reddy, Sushma; Robin, V. V.; Vishnudas, C. K.; Gupta, Pooja; Rheindt, Frank E.; Hooper, Daniel M.; and Ramakrishnan, Uma. Two New Genera of Songbirds Represent Endemic Radiations from the Shola Sky Islands of the Western Ghats, India. BMC Evolutionary Biology, 17, 31: 1-14, 2017. Retrieved from Loyola eCommons, Biology: Faculty Publications and Other Works, http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s12862-017-0882-6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Publications at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Biology: Faculty Publications and Other Works by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. © The Authors 2017 Authors Sushma Reddy, V. V. Robin, C. K. Vishnudas, Pooja Gupta, Frank E. Rheindt, Daniel M. Hooper, and Uma Ramakrishnan This article is available at Loyola eCommons: https://ecommons.luc.edu/biology_facpubs/60 Robin et al. -

List of Birds of Vietnam

(List of birds of Vietnam) No. ENGLISH NAME SCIENTIFIC NAME Note 1 Lesser Whistling-Duck Dendrocygna javanica 2 Bar-headed Goose Anser indicus Rare/Accidental 3 Graylag Goose Anser anser 4 Comb Duck Sarkidiornis melanotos 5 Ruddy Shelduck Tadorna ferruginea 6 Common Shelduck Tadorna tadorna 7 Cotton Pygmy-Goose Nettapus coromandelianus 8 Mandarin Duck Aix galericulata Rare/Accidental 9 Garganey Spatula querquedula 10 Northern Shoveler Spatula clypeata 11 Gadwall Mareca strepera 12 Falcated Duck Mareca falcata Near-threatened 13 Eurasian Wigeon Mareca penelope 14 Indian Spot-billed Duck Anas poecilorhyncha 15 Eastern Spot-billed Duck Anas zonorhyncha 16 Mallard Anas platyrhynchos Rare/Accidental 17 Northern Pintail Anas acuta 18 Green-winged Teal Anas crecca 19 White-winged Duck Asarcornis scutulata Endangered 20 Common Pochard Aythya ferina Vulnerable 21 Ferruginous Duck Aythya nyroca Near-threatened 22 Baer's Pochard Aythya baeri Critically endangered 23 Tufted Duck Aythya fuligula 24 Greater Scaup Aythya marila 25 Red-breasted Merganser Mergus serrator Rare/Accidental 26 Scaly-sided Merganser Mergus squamatus Endangered 27 Annam Partridge Arborophila merlini Endemic 28 Hill Partridge Arborophila torqueola 29 Rufous-throated Partridge Arborophila rufogularis 30 Bar-backed Partridge Arborophila brunneopectus 31 Orange-necked Partridge Arborophila davidi Endemic Near-threatened 32 Green-legged Patridge Arborophila chloropus 33 Crested Argus Rheinardia ocellata Near-threatened 34 Green Peafowl Pavo muticus Endangered 35 Germain's Peacock-Pheasant -

'The Devil Is in the Detail': Peer-Review of the Wildlife Conservation Plan By

‘The devil is in the detail’: Peer-review of the Wildlife Conservation Plan by the Wildlife Institute of India for the Etalin Hydropower Project, Dibang Valley Chintan Sheth1, M. Firoz Ahmed2*, Sayan Banerjee3, Neelesh Dahanukar4, Shashank Dalvi1, Aparajita Datta5, Anirban Datta Roy1, Khyanjeet Gogoi6, Monsoonjyoti Gogoi7, Shantanu Joshi8, Arjun Kamdar8, Jagdish Krishnaswamy9, Manish Kumar10, Rohan K. Menzies5, Sanjay Molur4, Shomita Mukherjee11, Rohit Naniwadekar5, Sahil Nijhawan1, Rajeev Raghavan12, Megha Rao5, Jayanta Kumar Roy2, Narayan Sharma13, Anindya Sinha3, Umesh Srinivasan14, Krishnapriya Tamma15, Chihi Umbrey16, Nandini Velho1, Ashwin Viswanathan5 & Rameshori Yumnam12 1Independent researcher, Ananda Nilaya, 4th Main Road, Kodigehalli, Bengaluru, Karnataka 560097, India Email: [email protected] (corresponding author) 2Herpetofauna Research and Conservation Division, Aaranyak, Guwahati, Assam. 3National Institute of Advanced Studies, Bengaluru, Karnataka. 4Zoo Outreach Organization, Coimbatore, Tamil Nadu. 5Nature Conservation Foundation, Bengaluru, Karnataka. 6TOSEHIM, Regional Orchids Germplasm Conservation and Propagation Centre, Assam Circle, Assam. 7Bombay Natural History Society, Mumbai, Maharashtra. 8National Centre for Biological Sciences, Bengaluru, Karnataka. 9Ashoka Trust for Research in Ecology and the Environment, Bengaluru, Karnataka. 10Centre for Ecology Development and Research, Uttarakhand. 11Sálim Ali Centre for Ornithology and Natural History (SACON), Coimbatore, Tamil Nadu. 12South Asia IUCN Freshwater Fish