Manufacturing Motown

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Young Americans to Emotional Rescue: Selected Meetings

YOUNG AMERICANS TO EMOTIONAL RESCUE: SELECTING MEETINGS BETWEEN DISCO AND ROCK, 1975-1980 Daniel Kavka A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC August 2010 Committee: Jeremy Wallach, Advisor Katherine Meizel © 2010 Daniel Kavka All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Jeremy Wallach, Advisor Disco-rock, composed of disco-influenced recordings by rock artists, was a sub-genre of both disco and rock in the 1970s. Seminal recordings included: David Bowie’s Young Americans; The Rolling Stones’ “Hot Stuff,” “Miss You,” “Dance Pt.1,” and “Emotional Rescue”; KISS’s “Strutter ’78,” and “I Was Made For Lovin’ You”; Rod Stewart’s “Do Ya Think I’m Sexy“; and Elton John’s Thom Bell Sessions and Victim of Love. Though disco-rock was a great commercial success during the disco era, it has received limited acknowledgement in post-disco scholarship. This thesis addresses the lack of existing scholarship pertaining to disco-rock. It examines both disco and disco-rock as products of cultural shifts during the 1970s. Disco was linked to the emergence of underground dance clubs in New York City, while disco-rock resulted from the increased mainstream visibility of disco culture during the mid seventies, as well as rock musicians’ exposure to disco music. My thesis argues for the study of a genre (disco-rock) that has been dismissed as inauthentic and commercial, a trend common to popular music discourse, and one that is linked to previous debates regarding the social value of pop music. -

Marvin Gaye As Vocal Composer 63 Andrew Flory

Sounding Out Pop Analytical Essays in Popular Music Edited by Mark Spicer and John Covach The University of Michigan Press • Ann Arbor Copyright © by the University of Michigan 2010 All rights reserved Published in the United States of America by The University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America c Printed on acid-free paper 2013 2012 2011 2010 4321 No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, or otherwise, without the written permission of the publisher. A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Sounding out pop : analytical essays in popular music / edited by Mark Spicer and John Covach. p. cm. — (Tracking pop) Includes index. ISBN 978-0-472-11505-1 (cloth : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-0-472-03400-0 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Popular music—History and criticism. 2. Popular music— Analysis, appreciation. I. Spicer, Mark Stuart. II. Covach, John Rudolph. ML3470.S635 2010 781.64—dc22 2009050341 Contents Preface vii Acknowledgments xi 1 Leiber and Stoller, the Coasters, and the “Dramatic AABA” Form 1 john covach 2 “Only the Lonely” Roy Orbison’s Sweet West Texas Style 18 albin zak 3 Ego and Alter Ego Artistic Interaction between Bob Dylan and Roger McGuinn 42 james grier 4 Marvin Gaye as Vocal Composer 63 andrew flory 5 A Study of Maximally Smooth Voice Leading in the Mid-1970s Music of Genesis 99 kevin holm-hudson 6 “Reggatta de Blanc” Analyzing -

“My Girl”—The Temptations (1964) Added to the National Registry: 2017 Essay by Mark Ribowsky (Guest Post)*

“My Girl”—The Temptations (1964) Added to the National Registry: 2017 Essay by Mark Ribowsky (guest post)* The Temptations, c. 1964 The Temptations’ 1964 recording of “My Girl” came at a critical confluence for the group, the Motown label, and a culture roiling with the first waves of the British invasion of popular music. The five-man cell of disparate souls, later to be codified by black disc jockeys as the “tall, tan, talented, titillating, tempting Temptations,” had been knocking around Motown’s corridors and studio for three years, cutting six failed singles before finally scoring on the charts that year with Smokey Robinson’s cleverly spunky “The Way You Do the Things You Do” that winter. It rose to number 11 on the pop chart and to the top of the R&B chart, an important marker on the music landscape altered by the Beatles’ conquest of America that year. Having Smokey to guide them was incalculably advantageous. Berry Gordy, the former street hustler who had founded Motown as a conduit for Detroit’s inner-city voices in 1959, invested a lot of trust in the baby-faced Robinson, who as front man of the Miracles delivered the company’s seminal number one R&B hit and million-selling single, “Shop Around.” Four years later, in 1964, he wrote and produced Mary Wells’ “My Guy,” Motown’s second number one pop hit. Gordy conquered the black urban market but craved the broader white pop audience. The Temptations were riders on that train. Formed in 1959 by Otis Williams, a leather-jacketed street singer, their original lineup consisted of Williams, Elbridge “Al” Bryant, bass singer Melvin Franklin and tenors Eddie Kendricks and Paul Williams. -

Aaamc Issue 9 Chrono

of renowned rhythm and blues artists from this same time period lip-synch- ing to their hit recordings. These three aaamc mission: collections provide primary source The AAAMC is devoted to the collection, materials for researchers and students preservation, and dissemination of materi- and, thus, are invaluable additions to als for the purpose of research and study of our growing body of materials on African American music and culture. African American music and popular www.indiana.edu/~aaamc culture. The Archives has begun analyzing data from the project Black Music in Dutch Culture by annotating video No. 9, Fall 2004 recordings made during field research conducted in the Netherlands from 1998–2003. This research documents IN THIS ISSUE: the performance of African American music by Dutch musicians and the Letter ways this music has been integrated into the fabric of Dutch culture. The • From the Desk of the Director ...........................1 “The legacy of Ray In the Vault Charles is a reminder • Donations .............................1 of the importance of documenting and • Featured Collections: preserving the Nelson George .................2 achievements of Phyl Garland ....................2 creative artists and making this Arizona Dranes.................5 information available to students, Events researchers, Tribute.................................3 performers, and the • Ray Charles general public.” 1930-2004 photo by Beverly Parker (Nelson George Collection) photo by Beverly Parker (Nelson George Visiting Scholars reminder of the importance of docu- annotation component of this project is • Scot Brown ......................4 From the Desk menting and preserving the achieve- part of a joint initiative of Indiana of the Director ments of creative artists and making University and the University of this information available to students, Michigan that is funded by the On June 10, 2004, the world lost a researchers, performers, and the gener- Andrew W. -

Exhibition Keynote Speaker the Newark Public Library

THE PERFORMER The Newark Public Library Miche (pronounced “Mickey”) Braden is a singer, actor, musician, songwriter, arranger and musical Presents director. She is a product of the rich musical heritage of her hometown, Detroit, where she A Black History Celebration was an artist-in-residence with the Detroit Council of the Arts, the founder and former Opening Night lead singer of Straight Ahead (women’s jazz band), and was a protégé of Motown musi- cians Thomas “Beans” Bowles, Earl Van Dyke (leader of The Funk Brothers), and jazz master composer Harold McKinney. As a singer, Miche has performed with Re- gina Carter, Alexis P. Suter, Milt Hinton, Lionel Hampton and Frenchie Davis. She is featured on the James Carter re- lease Gardenia’s for Lady Day (Sony/Columbia), and ap- peared with him at Carnegie Hall. Miche performed “New York State of Mind” in Movin’ Out on Broadway, and was dubbed “Billy Joel’s Piano Woman” by Fox 5 News. Miche’s talented and versatile work can be heard on Diva Out of Bounds, Ms. Miche (available on iTunes and CD Baby). This Saturday JONATHAN CAPEHART ~ FEB 6th Centennial Hall ~ 2:00-4:00 PM Thursday, February 4, 2016 Pulitzer Prize-winning writer, Washington Post editorial board member, PostPartisan blogger Exhibition and MSNBC contributor, Jonathan Capehart, We Found Our Way: will be the keynote speaker on Saturday, Feb- Newark Portraits from the Great Migration ruary 6 at 2 PM, Centennial Hall. Born and raised in Newark, NJ and a gradu- ate of St. Benedict's Preparatory Keynote Speaker High School in Newark, Capehart will discuss "White Balance: Distortion of John Franklin Black Images on Television." Hosted by Emmy Senior Manager Office of External Affairs Award-winning anchor/reporter and FiOS 1 The National Museum of African American News Team anchor, Vanessa Tyler. -

The Social and Cultural Changes That Affected the Music of Motown Records from 1959-1972

Columbus State University CSU ePress Theses and Dissertations Student Publications 2015 The Social and Cultural Changes that Affected the Music of Motown Records From 1959-1972 Lindsey Baker Follow this and additional works at: https://csuepress.columbusstate.edu/theses_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Baker, Lindsey, "The Social and Cultural Changes that Affected the Music of Motown Records From 1959-1972" (2015). Theses and Dissertations. 195. https://csuepress.columbusstate.edu/theses_dissertations/195 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Publications at CSU ePress. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of CSU ePress. The Social and Cultural Changes that Affected the Music of Motown Records From 1959-1972 by Lindsey Baker A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of Requirements of the CSU Honors Program for Honors in the degree of Bachelor of Music in Performance Schwob School of Music Columbus State University Thesis Advisor Date Dr. Kevin Whalen Honors Committee Member ^ VM-AQ^A-- l(?Yy\JcuLuJ< Date 2,jbl\5 —x'Dr. Susan Tomkiewicz Dean of the Honors College ((3?7?fy/L-Asy/C/7^ ' Date Dr. Cindy Ticknor Motown Records produced many of the greatest musicians from the 1960s and 1970s. During this time, songs like "Dancing in the Street" and "What's Going On?" targeted social issues in America and created a voice for African-American people through their messages. Events like the Mississippi Freedom Summer and Bloody Thursday inspired the artists at Motown to create these songs. Influenced by the cultural and social circumstances of the Civil Rights Movement, the musical output of Motown Records between 1959 and 1972 evolved from a sole focus on entertainment in popular culture to a focus on motivating social change through music. -

Recreating the Ensemble Dynamic of Motown's Funk Brothers

6 Unsung Heroes: Recreating the Ensemble Dynamic of Motown’s Funk Brothers Vincent Perry Introduction By the early 1960s, the genre known as soul had become the most commercially successful of all the crossover styles. Drawing on musical influences from the genres of gospel, jazz and blues, ‘soul’s success was as much due to a number of labels, so-called “house sounds”, and little- known bands, as it was to specific performers or songwriters’ (Borthwick and Moy, 2004, p. 5). Following on from the pioneer releases of Ray Charles and Sam Cooke, a Detroit-based independent label would soon become the ‘most successful and high profile of all the soul labels’ (Borthwick and Moy, 2004, p. 5). Throughout the early 1960s, Berry Gordy’s Tamla Motown dominated the domestic US pop and R&B charts with its assembly-line approach to music production (Moorefield, 2005, p. 21), which resulted in a distinctive sound that was shared by all the label’s artists. However, in 1963, the company ‘achieved its international breakthrough’ shortly after signing a landmark distribution deal with EMI in the UK (Borthwick and Moy, 2004, p. 5). Gordy’s headquarters—a seemingly humble, suburban 95 POPULAR MUSIC, STARS AND STARDOM residence—was ambitiously named Hitsville USA and, throughout the 1960s, it became a hub for pop record success. Emerson (2005, p. 194) acknowledged Motown’s industry presence when he noted: Motown was muscling in on the market for dance music. Streamlined, turbo-charged singles by the Marvelettes, Martha and the Vandellas, and the Supremes rolled off the Detroit assembly line … Berry Gordy’s ‘Sound of Young America’ challenged the Brill Building, 1650 Broadway, and 711 Fifth Avenue as severely as the British Invasion because it proved that black artists did not need white writers to reach a broad pop audience. -

~Tate of \!Cennessee

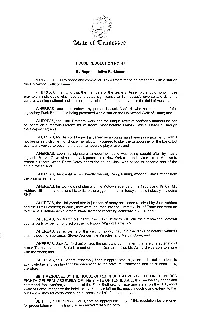

~tate of \!Cennessee HOUSE RESOLUTION NO. 47 By Representative Parkinson A RESOLUTION to honor and commend Jack Ashford for being presented with a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. WHEREAS, it is fitting that the members of the General Assembly should honor those exemplary individuals who have contributed significantly to Tennessee's diverse and dynamic culture, winning national and international acclaim for their endeavors in the field of music; and WHEREAS, one such noteworthy person is Jack Ashford, who as a member of the legendary Funk Brothers, is being presented with a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame; and WHEREAS, the Funk Brothers' work and the unique rattle of Ashford's tambourine can be heard on numerous Motown music tracks; most notably, Marvin Gaye's "Heard it Through the Grapevine"; and WHEREAS, Mr. Ashford began his career as a young man touring in a jazz band; with it not being his instrument of choice, he reluctantly agreed to play the tambourine for the band, but eventually vowed to become the best tambourine player ever; and WHEREAS, soon his signature tambourine sound was being sought after by music legends; Marvin Gaye witnessed Jack perform in a New York club and invited him to Motown to record a record; when Barry Gordy heard the sound, Jack was asked to become part of the studio roster; and WHEREAS, Jack Ashford is currently the only living, touring, working Funk Brother from the original ~et; and WHEREAS, his work did not stop with the Motown legends of the 1960's and 1970's; Mr. -

The Assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and the Birth of Funk Culture

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 2013 Funk My Soul: The Assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. And the Birth of Funk Culture Domenico Rocco Ferri Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Ferri, Domenico Rocco, "Funk My Soul: The Assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. And the Birth of Funk Culture" (2013). Dissertations. 664. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss/664 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 2013 Domenico Rocco Ferri LOYOLA UNIVERSITY CHICAGO FUNK MY SOUL: THE ASSASSINATION OF DR. MARTIN LUTHER KING JR. AND THE BIRTH OF FUNK CULTURE A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY PROGRAM IN HISTORY BY DOMENICO R. FERRI CHICAGO, IL AUGUST 2013 Copyright by Domenico R. Ferri, 2013 All rights reserved. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Painstakingly created over the course of several difficult and extraordinarily hectic years, this dissertation is the result of a sustained commitment to better grasping the cultural impact of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s life and death. That said, my ongoing appreciation for contemporary American music, film, and television served as an ideal starting point for evaluating Dr. -

James Jamerson 2000.Pdf

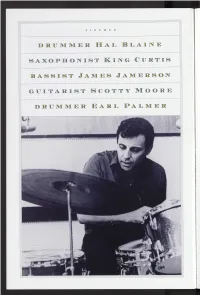

able to conjure up the one lick, fill or effect that perfected albums. Live at Fillmore West exhibits Curtis the bandleader the sound. Some of his best work is found on those records. at his absolute best on a night when his extraordinary players There’s little else to say about Hal Blaine that the music included Bernard Purdie, Jerry Jemmott and Cornell Dupree. itself doesn’t communicate. But I’ll tell you one experience I His 1962 “Soul Twist” single MfclNumber One on the R&B had that showed me just how widespread his influence has charts and the Top Twenty on the pop charts, and made such been. Hal was famous for rubber-stamping his name upon an impression on Sam Cooke that he referred to it in “Having all the charts to which he contributed. In 1981, after one of a Party:” But nothing King Curtis did on his own ever scaled our concerts at Wembley Arena, Bruce asked me into his the Promethean heights of his sax work as a sideman, where dressing room. He pointed to the wall and said, “Look at he mastered the ability to be an individual within a group, that.” I looked at the wall but didn’t see anything except peel standing out but never overshadowing the artists he was sup ing wallpaper. “Look closer,” he said. Finally, I kneeled down porting and mastering the little nuances that made winners to the spot he was pointing to, and - to my great surprise - of the records on which he played. His was a rare voice j a rare in a crack in the paper, rubber-stamped on the w a ll, there it sensibility, a rare soul; and that sound - whether it be caress was: HAL BLAINE STRIKES AGAIN. -

TABLE of CONTENTS ______Page Acknowledgements Viii Credits X Forward Xii Introduction Xiii

TABLE OF CONTENTS _______ Page Acknowledgements viii Credits x Forward xii Introduction xiii Part 1 Funky Beginnings 3 Don’t Look Back 5 Five Bucks A Session (And A Bowl Of Soup) 12 Welcome To The Apollo 18 Igor & The Funk Brothers (Part One) 25 Igor & The Funk Brothers (Part Two) 29 We’re In The Money 36 Stompin’ At The Chit Chat 41 Don’t Mess With James 46 Leave It To Jamerson 49 Dr. Jamerson & Mr. Hyde 52 Growing Pains 55 The Fall Of The King 65 Coda 76 Part 2 Anatomy Of A Sound 81 B-15’s And Funk Machines 84 The Cast 87 Discography 88 Igor’s Chromatic Exercise 91 An Appreciation Of The Style – by Anthony Jackson 92 Part 3 Stars And Scores 99 Tape Contents 101 Paul McCartney 102 James Jamerson Jr. (What’s Going On, Ain’t That Peculiar, My Guy) 103 Will Lee (I heard It Through The Grapevine) 108 John Entwhistle (Ain’t Too Proud To Beg, Going To A Go-Go, 111 Contract On Love) Gerald Veasley (Darling Dear, You Can’t Hurry Love, Shotgun) 113 Phil Chen (Reach Out, I’ll Be There) 118 Pino Paladino (For Once In my Life, I Second That Emotion 121 I Know I’m Losing You) Geddy Lee (Get Ready) 125 Chuck Rainey (Bernadette, Cloud Nine, You Keep Me Hanging On) 127 The Philadelphia Int. Rhythm Section (Ain’t No Mountain High Enough) 132 Freddy Washington (I’m Gonna Make You Love Me, 136 Girl Why You Wanna Make Me Blue) Garry Tallent (Baby Love) 139 Allen McGrier (It’s A Shame) 141 John Patitucci (How Sweet It Is, Heat Wave, Mickey’s Monkey) 143 Jimmy Haslip (Don’t Mess With Bill, It’s The Same Old Song, 147 Shake Me Wake Me) Bob Babbitt (Ain’t Nothing -

RB HOF History 4.Pdf

THE INDUCTION CEREMONIES & WHITE PARTY HISTORY 2013-2020 Duke Fakir Gerald Austin of Bobby Rush The Bar-Kays The Four Tops Founder of TV-ONE Cathy Hughes The Manhattans Denise LaSalle The Legendary Whispers Morgan Freeman Honored in 2014 Dionne Warwick Norm N. Nite The Rhythm & Blues Hall of Fame was established in 2010 and the first induction ceremony was held on August 17, 2013. Since then, it has become an annual event celebrating singers, songwriters, groups, producers, radio personalities, night club owners, and other individuals (and even places and companies) which have significantly contributed to the R&B field. Here is list of over 200 inductees from 2013-2020: A Bert Dearing (2017) Nite Club Owner Al Abrams (2016) Public Relations The Delfonics (2014) Vocal group Barbara Acklin (2017) Singer & Songwriter Detroit Emeralds (2015) Vocal Group The Andantes (2014) Vocal group Bo Diddley (2017) Singer Jazzi Anderson (2015) Radio Host Fats Domino (2016) Singer & Songwriter Louis Armstrong (2017) Musician, Band Leader The Dramatics (2013) Vocal group The Drifters (2018) Vocal Group Freddie Arrington (2013) Master of Ceremonies, Leo’s Casino Night Club Ernie Durham (2017) Radio Host B The Dynamic Superiors (2013) Vocal group Hank Ballard & The Midnighters (2015) Vocal group Band Of Gypsys (2019) Band E The Elgins (2018) Vocal Group The Bar-Kays (2015) Band Enchantment (2013) Vocal group JJ Barnes (2015) Singer Ahmet Ertegun (2017) Record Label Executive Ortheia Barnes-Kennerly (2015) Singer Charles Evers (2017) Civil Rights Activist,