And What Is Soul Music?)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Gnostic Myth of Sophia in Dark City (1998) Fryderyk Kwiatkowski Jagiellonian University in Kraków, [email protected]

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by The University of Nebraska, Omaha Journal of Religion & Film Volume 21 Article 34 Issue 1 April 2017 4-1-2017 How To Attain Liberation From a False World? The Gnostic Myth of Sophia in Dark City (1998) Fryderyk Kwiatkowski Jagiellonian University in Kraków, [email protected] Recommended Citation Kwiatkowski, Fryderyk (2017) "How To Attain Liberation From a False World? The Gnostic Myth of Sophia in Dark City (1998)," Journal of Religion & Film: Vol. 21 : Iss. 1 , Article 34. Available at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/jrf/vol21/iss1/34 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Religion & Film by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. How To Attain Liberation From a False World? The Gnostic Myth of Sophia in Dark City (1998) Abstract In the second half of the 20th century, a fascinating revival of ancient Gnostic ideas in American popular culture could be observed. One of the major streams through which Gnostic ideas are transmitted is Hollywood cinema. Many works that emerged at the end of 1990s can be viewed through the ideas of ancient Gnostic systems: The Truman Show (1998), The Thirteenth Floor (1999), The Others (2001), Vanilla Sky (2001) or The Matrix trilogy (1999-2003). In this article, the author analyses Dark City (1998) and demonstrates that the story depicted in the film is heavily indebted to the Gnostic myth of Sophia. -

Chris Billam-Smith

MEET THE TEAM George McMillan Editor-in-Chief [email protected] Remembrance day this year marks 100 years since the end of World War One, it is a time when we remember those who have given their lives fighting in the armed forces. Our features section in this edition has a great piece on everything you need to know about the day and how to pay your respects. Elsewhere in the magazine you can find interviews with The Undateables star Daniel Wakeford, noughties legend Basshunter and local boxer Chris Billam Smith who is now prepping for his Commonwealth title fight. Have a spooky Halloween and we’ll see you at Christmas for the next edition of Nerve Magazine! Ryan Evans Aakash Bhatia Zlatna Nedev Design & Deputy Editor Features Editor Fashion & Lifestyle Editor [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Silva Chege Claire Boad Jonathan Nagioff Debates Editor Entertainment Editor Sports Editor [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] 3 ISSUE 2 | OCTOBER 2018 | HALLOWEEN EDITION FEATURES 6 @nervemagazinebu Remembrance Day: 100 years 7 A whitewashed Hollywood 10 CONTENTS /Nerve Now My personal experience as an art model 13 CONTRIBUTORS FEATURES FASHION & LIFESTYLE 18 Danielle Werner Top tips for stress-free skin 19 Aakash Bhatia Paris Fashion Week 20 World’s most boring Halloween costumes 22 FASHION & LIFESTYLE Best fake tanning products 24 Clare Stephenson Gracie Leader DEBATES 26 Stephanie Lambert Zlatna Nedev Black culture in UK music 27 DESIGN Do we need a second Brexit vote? 30 DEBATES Ryan Evans Latin America refugee crisis 34 Ella Smith George McMillan Hannah Craven Jake Carter TWEETS FROM THE STREETS 36 Silva Chege James Harris ENTERTAINMENT 40 ENTERTAINMENT 7 Emma Reynolds The Daniel Wakeford Experience 41 George McMillan REMEMBERING 100 YEARS Basshunter: No. -

Music Video As Black Art

IN FOCUS: Modes of Black Liquidity: Music Video as Black Art The Unruly Archives of Black Music Videos by ALESSANDRA RAENGO and LAUREN MCLEOD CRAMER, editors idway through Kahlil Joseph’s short fi lm Music Is My Mis- tress (2017), the cellist and singer Kelsey Lu turns to Ishmael Butler, a rapper and member of the hip-hop duo Shabazz Palaces, to ask a question. The dialogue is inaudible, but an intertitle appears on screen: “HER: Who is your favorite fi lm- Mmaker?” “HIM: Miles Davis.” This moment of Black audiovisual appreciation anticipates a conversation between Black popular cul- ture scholars Uri McMillan and Mark Anthony Neal that inspires the subtitle for this In Focus dossier: “Music Video as Black Art.”1 McMillan and Neal interpret the complexity of contemporary Black music video production as a “return” to its status as “art”— and specifi cally as Black art—that self-consciously uses visual and sonic citations from various realms of Black expressive culture in- cluding the visual and performing arts, fashion, design, and, obvi- ously, the rich history of Black music and Black music production. McMillan and Neal implicitly refer to an earlier, more recogniz- able moment in Black music video history, the mid-1990s and early 2000s, when Hype Williams defi ned music video aesthetics as one of the single most important innovators of the form. Although it is rarely addressed in the literature on music videos, the glare of the prolifi c fi lmmaker’s infl uence extends beyond his signature lumi- nous visual style; Williams distinguished the Black music video as a creative laboratory for a new generation of artists such as Arthur Jafa, Kahlil Joseph, Bradford Young, and Jenn Nkiru. -

Young Americans to Emotional Rescue: Selected Meetings

YOUNG AMERICANS TO EMOTIONAL RESCUE: SELECTING MEETINGS BETWEEN DISCO AND ROCK, 1975-1980 Daniel Kavka A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC August 2010 Committee: Jeremy Wallach, Advisor Katherine Meizel © 2010 Daniel Kavka All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Jeremy Wallach, Advisor Disco-rock, composed of disco-influenced recordings by rock artists, was a sub-genre of both disco and rock in the 1970s. Seminal recordings included: David Bowie’s Young Americans; The Rolling Stones’ “Hot Stuff,” “Miss You,” “Dance Pt.1,” and “Emotional Rescue”; KISS’s “Strutter ’78,” and “I Was Made For Lovin’ You”; Rod Stewart’s “Do Ya Think I’m Sexy“; and Elton John’s Thom Bell Sessions and Victim of Love. Though disco-rock was a great commercial success during the disco era, it has received limited acknowledgement in post-disco scholarship. This thesis addresses the lack of existing scholarship pertaining to disco-rock. It examines both disco and disco-rock as products of cultural shifts during the 1970s. Disco was linked to the emergence of underground dance clubs in New York City, while disco-rock resulted from the increased mainstream visibility of disco culture during the mid seventies, as well as rock musicians’ exposure to disco music. My thesis argues for the study of a genre (disco-rock) that has been dismissed as inauthentic and commercial, a trend common to popular music discourse, and one that is linked to previous debates regarding the social value of pop music. -

“My Girl”—The Temptations (1964) Added to the National Registry: 2017 Essay by Mark Ribowsky (Guest Post)*

“My Girl”—The Temptations (1964) Added to the National Registry: 2017 Essay by Mark Ribowsky (guest post)* The Temptations, c. 1964 The Temptations’ 1964 recording of “My Girl” came at a critical confluence for the group, the Motown label, and a culture roiling with the first waves of the British invasion of popular music. The five-man cell of disparate souls, later to be codified by black disc jockeys as the “tall, tan, talented, titillating, tempting Temptations,” had been knocking around Motown’s corridors and studio for three years, cutting six failed singles before finally scoring on the charts that year with Smokey Robinson’s cleverly spunky “The Way You Do the Things You Do” that winter. It rose to number 11 on the pop chart and to the top of the R&B chart, an important marker on the music landscape altered by the Beatles’ conquest of America that year. Having Smokey to guide them was incalculably advantageous. Berry Gordy, the former street hustler who had founded Motown as a conduit for Detroit’s inner-city voices in 1959, invested a lot of trust in the baby-faced Robinson, who as front man of the Miracles delivered the company’s seminal number one R&B hit and million-selling single, “Shop Around.” Four years later, in 1964, he wrote and produced Mary Wells’ “My Guy,” Motown’s second number one pop hit. Gordy conquered the black urban market but craved the broader white pop audience. The Temptations were riders on that train. Formed in 1959 by Otis Williams, a leather-jacketed street singer, their original lineup consisted of Williams, Elbridge “Al” Bryant, bass singer Melvin Franklin and tenors Eddie Kendricks and Paul Williams. -

The Portrayal of African American Women in Hip-Hop Videos

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Master's Theses Graduate College 6-2005 The Portrayal of African American Women in Hip-Hop Videos Ladel Lewis Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses Part of the Sociology Commons Recommended Citation Lewis, Ladel, "The Portrayal of African American Women in Hip-Hop Videos" (2005). Master's Theses. 4192. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses/4192 This Masters Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE PORTRAYAL OF AFRICAN AMERICAN WOMEN IN HIP-HOP VIDEOS By Ladel Lewis A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The Graduate College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Department of Sociology Western Michigan University Kalamazoo, Michigan June 2005 Copyright by Ladel Lewis 2005 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to thankmy advisor, Dr. Zoann Snyder, forthe guidance and the patience she has rendered. Although she had a course reduction forthe Spring 2005 semester, and incurred some minor setbacks, she put in overtime in assisting me get my thesis finished. I appreciate the immediate feedback, interest and sincere dedication to my project. You are the best Dr. Snyder! I would also like to thank my committee members, Dr. Douglas Davison, Dr. Charles Crawford and honorary committee member Dr. David Hartman fortheir insightful suggestions. They always lent me an ear, whether it was fora new joke or about anything. -

Starr-Waterman American Popular Music Chapter 11: the 1970S: Rock Music, Disco, and the Popular Mainstream Key People Allman

Starr-Waterman American Popular Music Chapter 11: The 1970s: Rock Music, Disco, and the Popular Mainstream Key People Allman Brothers Band: Most important southern rock band of the late 1960s and early 1970s who reconnected the generative power of the blues to the mainstream of rock music. Barry White (1944‒2004): Multitalented African American singer, songwriter, arranger, conductor, and producer who achieved success as an artist in the 1970s with his Love Unlimited Orchestra; perhaps best known for his full, deep voice. Carlos Santana (b. 1947): Mexican-born rock guitarist who combined rock, jazz, and Afro-Latin elements on influential albums like Abraxas. Carole King (b. 1942): Singer-songwriter who recorded influential songs in New York’s Brill Building and later recorded the influential album Tapestry in 1971. Charlie Rich (b. 1932): Country performer known as the “Silver Fox” who won the Country Music Association’s Entertainer of the Year award in 1974 for his song “The Most Beautiful Girl.” Chic: Disco group who recorded the hit “Good Times.” Chicago: Most long-lived and popular jazz rock band of the 1970s, known today for anthemic love songs such as “If You Leave Me Now” (1976), “Hard to Say I’m Sorry” (1982), and “Look Away” (1988). David Bowie (1947‒2016): Glam rock pioneer who recorded the influential album The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars in 1972. Dolly Parton (b. 1946): Country music star whose flexible soprano voice, songwriting ability, and carefully crafted image as a cheerful sex symbol combined to gain her a loyal following among country fans. -

Television Academy Awards

2019 Primetime Emmy® Awards Ballot Outstanding Comedy Series A.P. Bio Abby's After Life American Housewife American Vandal Arrested Development Atypical Ballers Barry Better Things The Big Bang Theory The Bisexual Black Monday black-ish Bless This Mess Boomerang Broad City Brockmire Brooklyn Nine-Nine Camping Casual Catastrophe Champaign ILL Cobra Kai The Conners The Cool Kids Corporate Crashing Crazy Ex-Girlfriend Dead To Me Detroiters Easy Fam Fleabag Forever Fresh Off The Boat Friends From College Future Man Get Shorty GLOW The Goldbergs The Good Place Grace And Frankie grown-ish The Guest Book Happy! High Maintenance Huge In France I’m Sorry Insatiable Insecure It's Always Sunny in Philadelphia Jane The Virgin Kidding The Kids Are Alright The Kominsky Method Last Man Standing The Last O.G. Life In Pieces Loudermilk Lunatics Man With A Plan The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel Modern Family Mom Mr Inbetween Murphy Brown The Neighborhood No Activity Now Apocalypse On My Block One Day At A Time The Other Two PEN15 Queen America Ramy The Ranch Rel Russian Doll Sally4Ever Santa Clarita Diet Schitt's Creek Schooled Shameless She's Gotta Have It Shrill Sideswiped Single Parents SMILF Speechless Splitting Up Together Stan Against Evil Superstore Tacoma FD The Tick Trial & Error Turn Up Charlie Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt Veep Vida Wayne Weird City What We Do in the Shadows Will & Grace You Me Her You're the Worst Young Sheldon Younger End of Category Outstanding Drama Series The Affair All American American Gods American Horror Story: Apocalypse American Soul Arrow Berlin Station Better Call Saul Billions Black Lightning Black Summer The Blacklist Blindspot Blue Bloods Bodyguard The Bold Type Bosch Bull Chambers Charmed The Chi Chicago Fire Chicago Med Chicago P.D. -

Traditional Funk: an Ethnographic, Historical, and Practical Study of Funk Music in Dayton, Ohio

University of Dayton eCommons Honors Theses University Honors Program 4-26-2020 Traditional Funk: An Ethnographic, Historical, and Practical Study of Funk Music in Dayton, Ohio Caleb G. Vanden Eynden University of Dayton Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.udayton.edu/uhp_theses eCommons Citation Vanden Eynden, Caleb G., "Traditional Funk: An Ethnographic, Historical, and Practical Study of Funk Music in Dayton, Ohio" (2020). Honors Theses. 289. https://ecommons.udayton.edu/uhp_theses/289 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the University Honors Program at eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Traditional Funk: An Ethnographic, Historical, and Practical Study of Funk Music in Dayton, Ohio Honors Thesis Caleb G. Vanden Eynden Department: Music Advisor: Samuel N. Dorf, Ph.D. April 2020 Traditional Funk: An Ethnographic, Historical, and Practical Study of Funk Music in Dayton, Ohio Honors Thesis Caleb G. Vanden Eynden Department: Music Advisor: Samuel N. Dorf, Ph.D. April 2020 Abstract Recognized nationally as the funk capital of the world, Dayton, Ohio takes credit for birthing important funk groups (i.e. Ohio Players, Zapp, Heatwave, and Lakeside) during the 1970s and 80s. Through a combination of ethnographic and archival research, this paper offers a pedagogical approach to Dayton funk, rooted in the styles and works of the city’s funk legacy. Drawing from fieldwork with Dayton funk musicians completed over the summer of 2019 and pedagogical theories of including black music in the school curriculum, this paper presents a pedagogical model for funk instruction that introduces the ingredients of funk (instrumentation, form, groove, and vocals) in order to enable secondary school music programs to create their own funk rooted in local history. -

“Rapper's Delight”

1 “Rapper’s Delight” From Genre-less to New Genre I was approached in ’77. A gentleman walked up to me and said, “We can put what you’re doing on a record.” I would have to admit that I was blind. I didn’t think that somebody else would want to hear a record re-recorded onto another record with talking on it. I didn’t think it would reach the masses like that. I didn’t see it. I knew of all the crews that had any sort of juice and power, or that was drawing crowds. So here it is two years later and I hear, “To the hip-hop, to the bang to the boogie,” and it’s not Bam, Herc, Breakout, AJ. Who is this?1 DJ Grandmaster Flash I did not think it was conceivable that there would be such thing as a hip-hop record. I could not see it. I’m like, record? Fuck, how you gon’ put hip-hop onto a record? ’Cause it was a whole gig, you know? How you gon’ put three hours on a record? Bam! They made “Rapper’s Delight.” And the ironic twist is not how long that record was, but how short it was. I’m thinking, “Man, they cut that shit down to fifteen minutes?” It was a miracle.2 MC Chuck D [“Rapper’s Delight”] is a disco record with rapping on it. So we could do that. We were trying to make a buck.3 Richard Taninbaum (percussion) As early as May of 1979, Billboard magazine noted the growing popularity of “rapping DJs” performing live for clubgoers at New York City’s black discos.4 But it was not until September of the same year that the trend gar- nered widespread attention, with the release of the Sugarhill Gang’s “Rapper’s Delight,” a fifteen-minute track powered by humorous party rhymes and a relentlessly funky bass line that took the country by storm and introduced a national audience to rap. -

Crossing Over: from Black Rhythm Blues to White Rock 'N' Roll

PART2 RHYTHM& BUSINESS:THE POLITICAL ECONOMY OF BLACKMUSIC Crossing Over: From Black Rhythm Blues . Publishers (ASCAP), a “performance rights” organization that recovers royalty pay- to WhiteRock ‘n’ Roll ments for the performance of copyrighted music. Until 1939,ASCAP was a closed BY REEBEEGAROFALO society with a virtual monopoly on all copyrighted music. As proprietor of the com- positions of its members, ASCAP could regulate the use of any selection in its cata- logue. The organization exercised considerable power in the shaping of public taste. Membership in the society was generally skewed toward writers of show tunes and The history of popular music in this country-at least, in the twentieth century-can semi-serious works such as Richard Rodgers and Lorenz Hart, Cole Porter, George be described in terms of a pattern of black innovation and white popularization, Gershwin, Irving Berlin, and George M. Cohan. Of the society’s 170 charter mem- which 1 have referred to elsewhere as “black roots, white fruits.’” The pattern is built bers, six were black: Harry Burleigh, Will Marion Cook, J. Rosamond and James not only on the wellspring of creativity that black artists bring to popular music but Weldon Johnson, Cecil Mack, and Will Tyers.’ While other “literate” black writers also on the systematic exclusion of black personnel from positions of power within and composers (W. C. Handy, Duke Ellington) would be able to gain entrance to the industry and on the artificial separation of black and white audiences. Because of ASCAP, the vast majority of “untutored” black artists were routinely excluded from industry and audience racism, black music has been relegated to a separate and the society and thereby systematically denied the full benefits of copyright protection. -

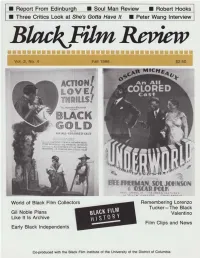

Report from Edinbur H • Soul Man Review • Robert Hooks Three Critics Look at She's Gotta Have It • Peter Wang Interview

Report From Edinbur h • Soul Man Review • Robert Hooks Three Critics Look at She's Gotta Have It • Peter Wang Interview World of Black Film Collectors Remembering Lorenzo Tucker- The Black. Gil Noble Plans Valentino Like It Is Archive Film Clips and News Early Black Independents Co-produced with the Black Film Institute of the University of the District of Columbia ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• Vol. 2, No. 4/Fa111986 'Peter Wang Breaks Cultural Barriers Black Film Review by Pat Aufderheide 10 SSt., NW An Interview with the director of A Great Wall p. 6 Washington, DC 20001 (202) 745-0455 Remembering lorenzo Tucker Editor and Publisher by Roy Campanella, II David Nicholson A personal reminiscence of one of the earliest stars of black film. ... p. 9 Consulting Editor Quick Takes From Edinburgh Tony Gittens by Clyde Taylor (Black Film Institute) Filmmakers debated an and aesthetics at the Edinburgh Festival p. 10 Associate EditorI Film Critic Anhur Johnson Film as a Force for Social Change Associate Editors by Charles Burnett Pat Aufderheide; Keith Boseman; Excerpts from a paper delivered at Edinburgh p. 12 Mark A. Reid; Saundra Sharp; A. Jacquie Taliaferro; Clyde Taylor Culture of Resistance Contributing Editors Excerpts from a paper p. 14 Bill Alexander; Carroll Parrott Special Section: Black Film History Blue; Roy Campanella, II; Darcy Collector's Dreams Demarco; Theresa furd; Karen by Saundra Sharp Jaehne; Phyllis Klotman; Paula Black film collectors seek to reclaim pieces of lost heritage p. 16 Matabane; Spencer Moon; An drew Szanton; Stan West. With a repon on effons to establish the Like It Is archive p.