Una Bibliografia.Cdr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

View the Floating Doctors Volunteer Handbook

Volunteer Handbook 1 Last Update 2016_07_30 Table of Contents 1. Floating Doctors a. Mission Statement b. Goals 2. Scope of Work a. Mobile Clinics b. Mobile Imaging c. Public Health Research d. Health Education e. Professional Training f. Patient Chaperoning g. Ethnomedicine h. Asilo i. Community Projects 3. Pre-Arrival Information a. Bocas del Toro b. Packing List c. Traveling to Bocas del Toro d. Arrival in Bocas 4. Volunteer Policies a. Work Standards b. Crew Code of Ethics and Conduct 5. Health and Safety a. Purpose b. Staying Healthy c. Safety Considerations 6. Financial Guidelines a. Volunteer Contributions b. Floating Doctors Contributions c. Personal Expenses 7. On-Site Logistics a. Community Guidelines b. Curfew c. Keys d. Laundry e. Resources f. Recycling 8. Living in Bocas a. Floating Doctors Discounts b. Groceries c. Restaurants d. Internet e. Phone 9. Basic Weekly Schedule a. Typical Weekly Schedule b. What to Expect on a Clinic Day c. What to Expect on a Multi-Day Clinic 10. Phone List 2 Last Update 2016_07_30 I. Floating Doctors Mission Statement The Floating Doctors’ ongoing mission is to reduce the present and future burden of disease in the developing world, and to promote improvements in health care delivery worldwide. Goals Our goals include: 1. Providing free acute and preventative health care services and delivering donated medical supplies to isolated areas. 2. Reducing child and maternal mortality through food safety/prenatal education, nutritional counseling and clean water solutions. 3. Studying and documenting local systems of health care delivery and identifying what progress have been made, what challenges remain, and what solutions exist to improve health care delivery worldwide. -

SWOT Analysis of Healthcare in Argentina 16

Global Longevity Governance Landscape 50 Countries Big Data Comparative Analysis of Longevity Progressiveness www.aginganalytics.com 50 Regions Practical Recommendations Countries with Low HALE and Life Expectancy and High Gap: 3 Recommendations United States Iran In death ratio some improvements are observed owing to The health system is one of the most complex systems with declining death rates from the three leading causes of death many variables and uncertainties. The management of this in the country -- heart disease, cancer and stroke. But in system needs trained managers. One of the current recent years, in United States costs of healthcare provision shortcomings is lack of those specifically trained for this have started to rise much more quickly with greater use of purpose. There is all high income inequality in the country. modern technological medicine. While spending is highest, Government should improve access in healthcare coverage the United States ranks not in the top in the world for its for the families with a low income. levels of health care. So, first of all, in order to improve HALE Turkey government should improve health insurance for poor Turkey faces a health care system inefficiencies. Infant population as there is big income inequality and reduce high mortality rate is relatively high and not all population had administrative costs for cost efficiency. The government health insurance, resulting in unequal healthcare access should focus on medical advances, some improvements in among different population groups. It is need to improve lifestyle, and screening and diagnosis. access for high-quality healthcare services and target the Estonia main causes of death through government initiatives. -

Financing Plan, Which Is the Origin of This Proposal

PROJECT DEVELOPMENT FACILITY REQUEST FOR PIPELINE ENTRY AND PDF-B APPROVAL AGENCY’S PROJECT ID: RS-X1006 FINANCINGIDB PDF* PLANIndicate CO-FINANCING (US$)approval 400,000date ( estimatedof PDFA ) ** If supplemental, indicate amount and date GEFSEC PROJECT ID: GEFNational ALLOCATION Contribution 60,000 of originally approved PDF COUNTRY: Costa Rica and Panama ProjectOthers (estimated) 3,000,000 PROJECT TITLE: Integrated Ecosystem Management of ProjectSub-Total Co-financing PDF Co- 960,000 the Binational Sixaola River Basin (estimated)financing: 8,500,000 GEF AGENCY: IDB Total PDF Project 960,000 OTHER EXECUTING AGENCY(IES): Financing:PDF A* DURATION: 8 months PDF B** (estimated) 500,000 GEF FOCAL AREA: Biodiversity PDF C GEF OPERATIONAL PROGRAM: OP12 Sub-Total GEF PDF 500,000 GEF STRATEGIC PRIORITY: BD-1, BD-2, IW-1, IW-3, EM-1 ESTIMATED STARTING DATE: January 2005 ESTIMATED WP ENTRY DATE: January 2006 PIPELINE ENTRY DATE: November 2004 RECORD OF ENDORSEMENT ON BEHALF OF THE GOVERNMENT: Ricardo Ulate, GEF Operational Focal Point, 02/27/04 Ministry of Environment and Energy (MINAE), Costa Rica Ricardo Anguizola, General Administrator of the 01/13/04 National Environment Authority (ANAM), Panama This proposal has been prepared in accordance with GEF policies and procedures and meets the standards of the GEF Project Review Criteria for approval. IA/ExA Coordinator Henrik Franklin Janine Ferretti Project Contact Person Date: November 8, 2004 Tel. and email: 202-623-2010 1 [email protected] PART I - PROJECT CONCEPT A - SUMMARY The bi-national Sixaola river basin has an area of 2,843.3 km2, 19% of which are in Panama and 81% in Costa Rica. -

Panama Breached Its Obligations Under the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights to Protect the Rights of Its Indigenous People

Panama Breached its Obligations under the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights to Protect the Rights of Its Indigenous People Respectfully submitted to the United Nations Human Rights Committee on the occasion of its consideration of the Third Periodic Report of Panama pursuant to Article 40 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights Hearings of the United Nations Human Rights Committee New York City, United States of America 24 - 25 March 2008 Prepared and submitted by the Program in International Human Rights Law of Indiana University School of Law at Indianapolis, Indiana, and the International Human Rights Law Society of Indiana University School of Law at Indianapolis, Indiana. Principal Authors, Editors and Researchers: Ms. Megan Alvarez, J.D. candidate, Indiana University School of Law at Indianapolis Ms. Carmen Brown, J.D. candidate, Indiana University School of Law at Indianapolis Ms. Susana Mellisa Alicia Cotera Benites, LL.M International Human Rights Law (Indiana University School of Law at Indianapolis), Bachelor’s in Law (University of Lima, Law School) Ms. Vanessa Campos, Bachelor Degree in Law and Political Science (University of Panama) Ms. Monica C. Magnusson, J.D. candidate, Indiana University School of Law at Indianapolis Mr. David A. Rothenberg, J.D. candidate, Indiana University School of Law at Indianapolis Mr. Jhon Sanchez, LL.B, MFA, LL.M (International Human Rights Law), J.D. candidate, Indiana University School of Law at Indianapolis Mr. Nelson Taku, LL.B, LL.M candidate in International Human Rights Law, Indiana University School of Law at Indianapolis Ms. Eva F. Wailes, J.D. candidate, Indiana University School of Law at Indianapolis Program in International Human Rights Law Director: George E. -

Socioeconomic Characterization of Bocas Del Toro in Panama: an Application of Multivariate Techniques

Revista Brasileira de Gestão e Desenvolvimento Regional G&DR. V. 16, N. 3, P. 59-71, set-dez/2020. Taubaté, SP, Brasil. ISSN: 1809-239X Received: 11/14/2019 Accepted: 04/26/2020 SOCIOECONOMIC CHARACTERIZATION OF BOCAS DEL TORO IN PANAMA: AN APPLICATION OF MULTIVARIATE TECHNIQUES CARACTERIZACIÓN SOCIOECONÓMICA DE BOCAS DEL TORO EN PANAMÁ: UNA APLICACIÓN DE TÉCNICAS MULTIVARIADAS Barlin Orlando Olivares1 Jacob Pitti2 Edilberto Montenegro3 Abstract The objective of this work was to identify the main socioeconomic characteristics of the villages with an agricultural vocation in the Bocas del Toro district, Panama, through multivariate techniques. The two principal components that accounted for 84.0% of the total variation were selected using the Principal Components Analysis. This allowed a classification in three strata, discriminating the populated centers of greater agricultural activity in the district. The study identified that the factors with the greatest impact on the characteristics of the population studied were: the development of agriculture in indigenous territories, the proportion of economically inactive people and economic occupation other than agriculture; This characterization serves as the first approach to the study of sustainable land management in indigenous territories. Keywords: Applied Economy, Biodiversity, Crops, Multivariate Statistics, Sustainability. Resumen El objetivo de este trabajo fue identificar las principales características socioeconómicas de los poblados con vocación agrícola del distrito Bocas del Toro, Panamá, a través de técnicas multivariadas. Mediante el Análisis de Componentes Principales se seleccionaron los primeros dos componentes que explicaban el 84.0 % de la variación total. Esto permitió una clasificación en tres estratos, discriminando los centros poblados de mayor actividad agrícola en el distrito. -

Panama 2018 International Religious Freedom Report

PANAMA 2018 INTERNATIONAL RELIGIOUS FREEDOM REPORT Executive Summary The constitution, laws, and executive decrees provide for freedom of religion and worship and prohibit discrimination based on religion. The constitution recognizes Roman Catholicism as the religion of the majority of citizens but not as the state religion. In March the Ministry of Education issued a resolution allowing girls attending public schools in the provinces of Panama City and Herrera to wear the hijab. Public schools continued to teach Catholicism, but parents could exempt their children from religion classes. Some non-Catholic groups continued to state the government provided preferential distribution of subsidies to small Catholic- run private schools for salaries and operating expenses and cited the level of government support given to the Catholic Church in preparation for the January 2019 World Youth Day. Local Catholic organizers continued to invite members of other religious denominations to participate. Some social media commentators criticized the use of public funds for the religious event. On August 16, the Interreligious Institute of Panama, an interfaith organization, held a public gathering entitled, “Interfaith Coexistence towards a Culture of Peace.” Approximately 100 individuals attended. The institute’s objectives included providing a coordination mechanism for interfaith activities and promoting mutual respect and appreciation among various religious groups. On August 29, the Panama Chapter of the Soka Gakkai International Buddhist Cultural Center hosted its Second Interreligious Dialogue with panelists from the Baha’i Spiritual Community, Kol-Shearith Jewish Congregation, Krishna-Hindu community, and Catholic Church. Embassy officials met on several occasions with government officials and raised questions about fairness in distribution of education subsidies for religious schools and the need for equal treatment of all religious groups before the law. -

Panama's Dollarized Economy Mainly Depends on a Well-Developed Services Sector That Accounts for 80 Percent of GDP

LATIN AMERICAN SOCIO-RELIGIOUS STUDIES PROGRAM - PROGRAMA LATINOAMERICANO DE ESTUDIOS SOCIORRELIGIOSOS (PROLADES) ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RELIGIOUS GROUPS IN LATIN AMERICA AND THE CARIBBEAN: RELIGION IN PANAMA SECOND EDITION By Clifton L. Holland, Director of PROLADES Last revised on 3 November 2020 PROLADES Apartado 86-5000, Liberia, Guanacaste, Costa Rica Telephone (506) 8820-7023; E-Mail: [email protected] Internet: http://www.prolades.com/ ©2020 Clifton L. Holland, PROLADES 2 CONTENTS Country Summary 5 Status of Religious Affiliation 6 Overview of Panama’s Social and Political Development 7 The Roman Catholic Church 12 The Protestant Movement 17 Other Religions 67 Non-Religious Population 79 Sources 81 3 4 Religion in Panama Country Summary Although the Republic of Panama, which is about the size of South Carolina, is now considered part of the Central American region, until 1903 the territory was a province of Colombia. The Republic of Panama forms the narrowest part of the isthmus and is located between Costa Rica to the west and Colombia to the east. The Caribbean Sea borders the northern coast of Panama, and the Pacific Ocean borders the southern coast. Panama City is the nation’s capital and its largest city with an urban population of 880,691 in 2010, with over 1.5 million in the metropolitan area. The city is located at the Pacific entrance of the Panama Canal , and is the political and administrative center of the country, as well as a hub for banking and commerce. The country has an area of 30,193 square miles (75,417 sq km) and a population of 3,661,868 (2013 census) distributed among 10 provinces (see map below). -

Exploring the Y Chromosomal Ancestry of Modern Panamanians

RESEARCH ARTICLE Exploring the Y Chromosomal Ancestry of Modern Panamanians Viola Grugni1, Vincenza Battaglia1, Ugo Alessandro Perego2,3, Alessandro Raveane1, Hovirag Lancioni3, Anna Olivieri1, Luca Ferretti1, Scott R. Woodward2, Juan Miguel Pascale4, Richard Cooke5, Natalie Myres2,6, Jorge Motta4, Antonio Torroni1, Alessandro Achilli1,3, Ornella Semino1* 1 Department of Biology and Biotechnology, University of Pavia, Pavia, Italy, 2 Sorenson Molecular Genealogy Foundation, Salt Lake City, Utah, United States of America, 3 Department of Chemistry, Biology and Biotechnology, University of Perugia, Perugia, Italy, 4 Instituto Conmemorativo Gorgas de Estudios de la Salud, Panama City, Panama, 5 Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, Panama City, Panama, 6 Ancestry, Provo, Utah, United States of America * [email protected] Abstract OPEN ACCESS Geologically, Panama belongs to the Central American land-bridge between North and Citation: Grugni V, Battaglia V, Perego UA, Raveane South America crossed by Homo sapiens >14 ka ago. Archaeologically, it belongs to a A, Lancioni H, Olivieri A, et al. (2015) Exploring the Y Chromosomal Ancestry of Modern Panamanians. wider Isthmo-Colombian Area. Today, seven indigenous ethnic groups account for 12.3% PLoS ONE 10(12): e0144223. doi:10.1371/journal. of Panama’s population. Five speak Chibchan languages and are characterized by low pone.0144223 genetic diversity and a high level of differentiation. In addition, no evidence of differential Editor: Francesc Calafell, Universitat Pompeu Fabra, structuring between maternally and paternally inherited genes has been reported in isth- SPAIN mian Chibchan cultural groups. Recent data have shown that 83% of the Panamanian gen- Received: March 31, 2015 eral population harbour mitochondrial DNAs (mtDNAs) of Native American ancestry. -

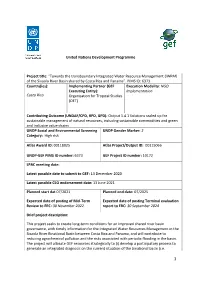

United Nations Development Programme Project Title

ƑPROJECT INDICATOR 10 United Nations Development Programme Project title: “Towards the transboundary Integrated Water Resource Management (IWRM) of the Sixaola River Basin shared by Costa Rica and Panama”. PIMS ID: 6373 Country(ies): Implementing Partner (GEF Execution Modality: NGO Executing Entity): Implementation Costa Rica Organisation for Tropical Studies (OET) Contributing Outcome (UNDAF/CPD, RPD, GPD): Output 1.4.1 Solutions scaled up for sustainable management of natural resources, including sustainable commodities and green and inclusive value chains UNDP Social and Environmental Screening UNDP Gender Marker: 2 Category: High risk Atlas Award ID: 00118025 Atlas Project/Output ID: 00115066 UNDP-GEF PIMS ID number: 6373 GEF Project ID number: 10172 LPAC meeting date: Latest possible date to submit to GEF: 13 December 2020 Latest possible CEO endorsement date: 13 June 2021 Planned start dat 07/2021 Planned end date: 07/2025 Expected date of posting of Mid-Term Expected date of posting Terminal evaluation Review to ERC: 30 November 2022. report to ERC: 30 September 2024 Brief project description: This project seeks to create long-term conditions for an improved shared river basin governance, with timely information for the Integrated Water Resources Management in the Sixaola River Binational Basin between Costa Rica and Panama, and will contribute to reducing agrochemical pollution and the risks associated with periodic flooding in the basin. The project will allocate GEF resources strategically to (i) develop a participatory process to generate an integrated diagnosis on the current situation of the binational basin (i.e. 1 Transboundary Diagnostic Analysis - TDA) and a formal binding instrument adopted by both countries (i.e. -

Epidemiologic Characteristics of Suicide in Panama, 2007–2016

medicina Article Epidemiologic Characteristics of Suicide in Panama, 2007–2016 1, 1 2,3 Virginia Núñez-Samudio y , Aris Jiménez-Domínguez , Humberto López Castillo and Iván Landires 1,4,5,* 1 Instituto de Ciencias Médicas, Las Tablas, Los Santos 0701, Panama; [email protected] (V.N.-S.); [email protected] (A.J.-D.) 2 Department of Health Sciences, College of Health Professions and Sciences, University of Central Florida, Orlando, FL 32816, USA; [email protected] 3 Department of Population Health Sciences, College of Medicine, University of Central Florida, Orlando, FL 32827, USA 4 Centro Regional Universitario de Azuero, CRUA, Universidad de Panamá, Chitré, Herrera 0601, Panama 5 Hospital Joaquín Pablo Franco Sayas, Región de Salud de Los Santos, Ministry of Health, Las Tablas, Los Santos 0701, Panama * Correspondence: [email protected] or [email protected]; Tel.: +507-6593-7727 Sección de Epidemiología, Departamento de Salud Pública, Región de Salud de Herrera, y Ministerio de Salud, Panama. Received: 22 July 2020; Accepted: 28 August 2020; Published: 31 August 2020 Abstract: Background and objectives: We aim to describe the demographic characteristics associated with suicide in Panama, to estimate the suicide mortality rate and years of potential life lost (YPLL) to suicide, and to explore the correlation of suicide rates with the Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI). We present a descriptive retrospective epidemiological report of suicide-related mortality (Panama, 2007–2016). Materials and Methods: Data were matched-merged to calculate unadjusted suicide mortality rates (overall, and by sex, age groups, and administrative region), YPLL, and coefficients (r) for the correlation of MPI and suicide rates. -

Panama Immigration & Residency Guide Research Your Relocation

Panama Immigration & Residency Guide Research your relocation with confidence Panama Immigration & Residency Guide SECTION 1: PANAMA AT A GLANCE 4 1 PANAMA IN A NUTSHELL 4 2 PANAMA AT A GLANCE 4 3 NEED MORE DETAIL? 4 4 PANAMA MAP 5 5 PANAMA PROVINCES 6 SECTION 2: VISAS & RESIDENCY 7 1 TOURIST VISA 7 2 RESIDENCY VISAS 8 2.1 FRIENDLY NATIONS VISA 8 2.2 PENSIONER (PENSIONADO) VISA 11 2.3 OTHER RESIDENCY VISAS 16 3 CÉDULA 16 4 CITIZENSHIP 17 SECTION 3: PANAMA EVERYDAY LIFE 19 1 SAFETY 19 1.1 OPINION OF LOCALS 19 1.2 OPINION OF EXPATS LIVING IN PANAMA 20 1.3 BETTER LIFE INDEX 21 1.4 SOCIAL PROGRESS INDEX 22 1.5 GLOBAL PEACE INDEX 22 1.6 THE GANG-MURDER CONNECTION 22 1.7 CONCLUSION 23 2 HEALTHCARE 23 2.1 A FEW FACTS AND FIGURES 24 2.2 AN OVERVIEW OF MAJOR MEDICAL FACILITIES AND PHARMACIES 24 2.3 AVAILABILITY OF HEALTH INSURANCE 26 2.4 WHAT OTHER EXPATS SAY 26 © Copyright Travel Hippi 2019 Page 1 of 38 3 OWNERSHIP 27 3.1 BUSINESS OWNERSHIP 27 3.2 REAL ESTATE OWNERSHIP 28 3.3 VEHICLE OWNERSHIP 30 4 COST OF LIVING 30 4.1 NUMBEO COST OF LIVING INDEX 31 4.2 EXPATISTAN COST OF LIVING RANKING 31 4.3 INTERNATIONS EXPAT INSIDER SURVEY 31 5 PANAMA BUDGET CALCULATOR 31 5.1 RENT 32 5.2 UTILITIES 33 5.3 HEALTH INSURANCE, HEALTHCARE 33 5.4 CONNECTIVITY, MOBILE SERVICE 34 5.5 INSURANCE (HOUSE CONTENT, CARS) 34 5.6 TRANSPORT (PUBLIC AND/OR OWN) 34 5.7 GROCERIES, HOUSEHOLD CLEANING 35 5.8 EDUCATION 36 5.9 CLOTHING & FOOTWEAR 36 5.10 SPORT, RECREATION, ENTERTAINMENT 37 © Copyright Travel Hippi 2019 Page 2 of 38 Updated: 1/23/19 | January 23rd, 2019 The Panama Guide is divided into three sections: At A Glance will give you a basic understanding of this unique Central American country by highlighting its most important features. -

Social Protection Systems in Latin America and the Caribbean: Panama

Project Document Social protection systems in Latin America and the Caribbean: Panama Alexis Rodríguez Mojica Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC) This document was prepared by Alexis Rodríguez, consultant with the Social Development Division of the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC), and is part of a series of studies on “Social protection systems in Latin America and the Caribbean”, edited by Simone Cecchini, Social Affairs Officer, and Claudia Robles, consultant, with the same Division. The author wish to thank Milena Lavigne and Humberto Soto for their valuable comments. The document was produced as part of the activities of the projects “Strengthening social protection” (ROA/1497) -and “Strengthening regional knowledge networks to promote the effective implementation of the United Nations development agenda and to assess progress” (ROA 161-7), financed by the United Nations Development Account. The views expressed in this document, which has been reproduced without formal editing, are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Organization. LC/W.526 Copyright © United Nations, November 2013. All rights reserved Printed in Santiago, Chile – United Nations ECLAC – Project Documents collection Social protection systems in Latin America and the Caribbean: Panama Contents Foreword .......................................................................................................................................... 5 I. Introduction .............................................................................................................................