A Guide to Preserving the Records of Truth Commissions Trudy Huskamp

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Start Typing Letter Here

Patricia Phelps de Cisneros Por más de cuatro décadas Patricia Phelps de Cisneros ha sido promotora de la educación y del arte, con un enfoque particular en América Latina. En la década de los setenta estableció, junto con su esposo Gustavo Cisneros, la Fundación Cisneros con sede en Caracas y Nueva York. La misión de la Fundación es contribuir a la educación en América Latina y dar a conocer el patrimonio cultural latinoamericano y sus múltiples contribuciones a la cultura global. La Colección Patricia Phelps de Cisneros, fundada a principios de la década de los noventa, es la principal iniciativa cultural de la Fundación Cisneros. Primeras influencias, trabajo y educación William Henry Phelps (1875-1965), bisabuelo de Patricia Cisneros, emprendió una expedición ornitológica en Venezuela, tras concluir su tercer año de licenciatura en la Universidad de Harvard. En ese viaje se enamoró del país y, al concluir sus estudios, regresó para asentarse permanentemente en el país. Phelps fue el gran emprendedor de su época, desarrollando prácticas modernas de negocios y estableciendo varias compañías, desde emisoras de televisión y estaciones de radio hasta importadoras de automóviles, refrigeradores, victrolas, máquinas de escribir, además que fue pionero en introducir el gusto por el béisbol en el país. Creó también la primera fundación en Venezuela. Su profundo interés por las ciencias naturales lo llevó a convertirse en un notable ornitólogo, a catalogar muchas especies aviarias de Suramérica y a publicar sus descubrimientos junto a su mentor, el científico Frank M. Chapman, en el Museo de Historia Natural de Nueva York (AMNH por sus siglas en inglés). -

Media Kit 2O15

media kit2O15 1O Reasons to Advertise in TV Latina 1 Editorial Excellence 6 Digital Editions For 19 years, our editorial group has published articles based on exhaustive Your ad will appear in the digital edition of the magazine, which reaches TV Latina media executives before the markets. research, with the journalistic integrity the industry deserves. has set 35,000 the standard for editorial excellence. Our interviews are always unique; unlike others, we do not publish interviews from press conferences or other promo- 7 Annual Guides tional materials. Our company also distributes two yearly guides, Guía de Canales and Guía de Dis- tribuidores, reaching programming executives in the region. Both guides are 3,000 2 The Most Influential Publishing Group distributed at NATPE, as well as various other markets throughout the year. TV Latina is part of World Screen, the most important, influential and respected group in the international media industry. This allows you to expand your target 8 Broad Online Coverage around the world at no additional cost. All printed and online information, includ- We offer our sponsors coverage throughout the year with our online newsletters Diario TV Latina ing content from all three of ’s editors, plus summaries and transla- TV Latina, TV Latina Semanal, TV Canales Semanal, TV Novelas y Series Semanal and tions in English, are done by our team, spearheaded by Anna Carugati, the TV Niños Semanal, which are sent to some executives in the region. Moreover, 9,000 group editorial director, and recipient of an Emmy award for journalism, a our nine English-language services reach an additional executives, pro- 35,000 duPont Columbia honorable mention and the Associated Press award for edit - viding you with a powerful information tool during the entire year. -

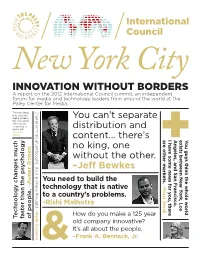

Innovation Without Borders

International Council NewINNOVATION York WITHOUT CityBORDERS A report on the 2012 International Council summit, an independent forum for media and technology leaders from around the world at the Paley Center for Media. Digital isn’t an afterthought, it’s a primary thought. The main thing is to close the digital divide in You can’t separate this new world, either you’re connected or distribution and you’re out. –Ricardo Salinas content... there’s are other markets. other markets. are there you, for some news I have Angeles, and San Francisco. Los York, New between exists think the whole world guys You no king, one without the other. –Jeff Bewkes You need to build the –Yossi Vardi –Yossi –Avner Ronen –Avner technology that is native to a country’s problems. -Rishi Malhotra –Herb Scannell How do you make a 125 year Technology changes much Technology than the psychology faster of people. old company innovative? It’s all about the people. –Frank A. Bennack, Jr. PC_ICBook_FINAL.indd 1 3/18/13 11:07 PM The Innovation Imperative In November 2012, The Paley Center for Media convened the twentieth meeting of the International Council since this perennial gathering of global media leaders began in 1995. Delegates from here in the US to countries in Latin America, Europe, Asia, and the Middle East, assembled at the Paley Center’s New York headquarters and the Time Warner Center for three days of dialogue and debate under the guiding theme “Innovation without Borders.” Certainly, as a longtime convener of international media leaders, The Paley Center has seen that growth goes hand-in-hand with corporate investment and partnerships across borders. -

Media Kit 2O16

TV Latina Mediakit_2016_Layout 1 7/7/15 2:52 PM Page 1 GUÍA DE CANALES 2015 GUÍA DE DISTRIBUIDORES 2015 WWW.TEVEBRASIL.COM JULHO/ AGOSTO 2014 EDIÇÃO ABTA Publicaciones TVBRASIL A hora é esta / Anthony Doyle da Turner TV Latina es una publicación en español que cubre las industrias de programación, cable y satélite en Latinoamérica, / Gustavo Leme da Fox EDICIÓN L.A. SCREENINGS WWW.TVLATINA.TV MAY O 2014 el mercado hispano en Estados Unidos e Iberia. Robert Bakish de Viacom / Elie Dekel de Saban Brands Contenidos digitales paraNIÑOS preescolares / ids Awards TV Peppa Pig Entrega de los International Emmy K Phil Davies y Neville Astley de / WWW.TVLATINA.TV MAYO 2014 TVNOVELASEDICIÓN L.A. SCREENINGS TV Niños es una revista completamente dedicada al negocio de la programación y mercancías infantiles. Novelas y series en plataformas no lineales / Fernando Gaitán TV Novelas es una revista enfocada en las últimas tendencias en este creciente género popular. TV Brasil es la revista dedicada a la cobertura del mercado de televisión brasileño escrita en portugués. La Guía de Canales es una guía portátil anual que provee una mirada completa a la industria de cable y satélite en Latinoamérica. Esta guía se distribuye en siete convenciones durante el año y se envía a ejecutivos en la región. 3 mil La Guía de Distribuidores es una guía portátil anual dedicada exclusivamente al negocio de la distribución de programación en Latinoamérica, el mercado hispano de Estados Unidos e Iberia. La guía está disponible en NATPE y los L.A. Screenings. También se envía a ejecutivos de programación en la región. -

Patricia Phelps De Cisneros

Patricia Phelps de Cisneros For more than four decades, Patricia Phelps de Cisneros has fervently supported education and the arts, with a particular focus on Latin America. In the 1970s, along with her husband, Gustavo A. Cisneros, she founded the New York City and Caracas-based Fundación Cisneros. Its mission is to improve education throughout Latin America and to foster global awareness of the region’s heritage and many contributions to world culture. The Colección Patricia Phelps de Cisneros, founded in the early 1990s, is the primary art-related program of the Fundación Cisneros. Early influences, work, and education Patricia Cisneros’s great-grandfather William Henry Phelps (1875—1965) undertook an ornithological expedition to Venezuela the summer after his junior year at Harvard University. During that trip, he fell in love with the country, and after graduation settled there permanently. Phelps was a great entrepreneur of his era who developed modern business practices and established many companies that ranged from television and radio networks to those that imported automobiles, refrigerators, Victrolas, typewriters, and Venezuela’s first taste of the game of baseball. He also started Venezuela's first foundation. Following his deep interest in natural science, he became a noted ornithologist who catalogued South American bird specimens and published his discoveries alongside his mentor, curator Frank M. Chapman, at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. A supporter as well as a scientific contributor to the AMNH in the following years, Phelps was awarded the position of Research Associate there in 1947. Patricia has credited her great-grandfather’s meticulous attention to the classification of his tropical birds as the inspiration for her awareness of the high level of care and cataloguing needed to preserve a collection and make it available for study. -

The Chapter the Cisneros Family Does Not Want Read in Venezuela

Click here for Full Issue of EIR Volume 12, Number 7, February 19, 1985 Dope, Inc. The chapter the Cisneros family does not want read in Venezuela Below is the chapter on Venezuela of EIR's Spanish-lan Cartaya, landed in jail on the lesser charges of income tax guage edition of Dope, Inc., titled Narcotrafi�o, S.A. For evasion. Details of the seamier side of the WFC operation further elaboration of references to the Venetian insurance arms for drugs in the Caribbean, financial capabilities made companies, the NorthAmerican-based Bronfman family, and available to the Castro government in Cuba-were included other topics from the world of dirty money, we recommend in the story. Interest was heightened by the fact that a Caracas the EIR cover story of Jan. 15, 1985. newspaper, Diario de Caracas, had just printed a picture of Until recently, Venezuela maintained a "privileged" relation ship to South America's drug traffic. Largely exempt from producing and processing narcotic:s until 1983, Venezuela served instead as a transshipment center and "banking house" for the drug trade. It was Venezuelan drug money, for ex ample, which led the way in laundering proceeds into Florida real estate, even before the Colombian mafia got the idea. Laundering from Venezuela into the United States through Florida grew so extensive that it became a common joke to say that Florida seceded from the Union-joining Venezuela as a new state. By 1980, public estimates placed Venezuelan real estate assets in Florida at over $1. 1 Qillion. A total of some $5 billion was "washed" through Venezuela in 1983, according to early 1984 public estimates of one Venezuelan police official. -

Access the Report

Americas Society and Council of the Americas — uniting opinion leaders to exchange ideas and create solutions to the challenges of the Americas today Americas Society Americas Society (AS) is the premier forum dedicated to education, debate, and dialogue in the Americas. Its mission is to foster an understanding of the contemporary political, social, and economic issues confronting Latin America, the Caribbean, and Canada, and to increase public awareness and appreciation of the diverse cultural heritage of the Americas and the importance of the Inter-American relationship.1 Council of the Americas Council of the Americas (COA) is the premier international business organization whose members share a common commitment to economic and social development, open markets, the rule of law, and democracy throughout the Western Hemisphere. The Council’s membership consists of leading international companies representing a broad spectrum of sectors including banking and finance, consulting services, consumer products, energy and mining, manufacturing, media, technology, and transportation.2 1 Americas Society is a tax-exempt public charity described in 501(c)(3) and 509(a)(1) of the Internal Revenue Code of 1986. 2 Council of the Americas is a tax-exempt business league under 501(c)(6) of the Internal Revenue Code of 1986, and as such, actively pursues lobbying activities to advance its purpose and the interests of its members. Americas Society Council of the Americas Annual Report 2016 Chairman’s Letter 2 President’s Letter 3 Americas Society -

Larouche's Enemies Falling: Cisneros Down in Venezuela

Click here for Full Issue of EIR Volume 21, Number 11, March 11, 1994 �TImInternational LaRouche's enemies:falling: Cisneros down in Venezuela by Jaime Garcia The demise of the corrupt Carlos Andres Perez (CAP) gov "twelve apostles." ernment in Venezuela appearsto beleading also to the fall of In the foUowing months,Ian unprecedented wave of ter the house of Cisneros, led by the brothers Gustavo and Ricar rorism was unleashed in the aountry, including letter bombs do Cisneros, archenemies of Lyndon LaRouche's interna to magistrates of the Venez�elan Supreme Court and car tional movement and viewed by internationalbusiness maga bombs set off in various locations in Caracas. These attacks zines as "the owners of Venezuela." did not succeed in preventing the Supreme Court from con On March 2, a Venezuelan judge issued 83 arrest war firming Perez's ouster from the presidency by late August, rants against the board of directors, managers, and advisers nor did they keep the leading opposition candidate to Perez of the Banco Latino, the once-powerful Venezuelan bank and his free trade economid policies, former Venezuelan whose failure last month triggered a financial and political President Rafael Caldera, from winning the December presi crisis in the country. Among those facing arrest for crimes dential elections. ranging from fraud to "criminal enterprise" is director Ricar During this period, the PL.. V continued to campaign with do Cisneros Rendiles, of the notorious Cisneros clan, whose the slogan "CAP Has Fallenj Down with His Gang," (i.e., head Gustavo Cisneros was responsible for securinga nation the "twelve apostles"). -

TV Latina Is Sent To

MEDIA KIT 2020/2O21 WWW.TVLATINA.TVTV ENEROLATINA 2020 EDICIÓN NATPE Panorama de las OTT en Latinoamérica / Robert Bakish de ViacomCBS / Robert Greenblatt de WarnerMedia Entertainment Michael Sheen / Christiane Amanpour / Damian Lewis / Ryan Eggold / James Farrell de Amazon Studios / Benjamín Salinas de TV Azteca Vincent Sadusky de Univision / John Hendricks de CuriosityStream / Fernando Barbosa de Disney / Alexander Marin de SPT Pierluigi Gazzolo de ViacomCBS / Marcos Santana de Telemundo Global Studios Circulation TV Latina is sent to: . Chairmen, presidents, CEOs and general managers . Cable operators, pan-regional media buyers and regional advertising agencies . Directors of programming, planning and co-productions . Program buyers for every program genre in all television stations, cable channels, pay-TV and satellite services, MSOs and OTT platforms in Latin America, the U.S. Hispanic market and Iberia Country Breakdown Mexico: 18% Argentina: 15% Brazil: 13% Chile, Uruguay & Paraguay: 11% U.S. Hispanic: 10% Spain & Portugal: 7% Central America & Caribbean: 6% Colombia: 5% Ecuador, Bolivia & Peru: 5% Venezuela: 4% Others: 6% WWW.TVLATINA.TV ENERO 2020 EDICIÓN NATPE TV SERIES GUÍA 2020 Tendencias de drama en América Latina / Miguel Ángel Silvestre / Jorge Dorado WWW.TVLATINA.TV MAYO 2019 EDICIÓN L.A. SCREENINGS Publications TV NIÑOS TV Latina is a Spanish-language publication covering the Contenido preescolar / Matteo Corradi de Mondo TV Claude de Saint Vincent de Media-Participations programming, OTT, cable and satellite industries -

2000 Spring Television Quarterly

JOURNAL OF THE NATIONAL ACADEMY OF TELEVISION ARTS AND SCIENCES LINCOLN CITY LIBRARIES "III III II III 1 III 3 3045 01854 1744 hub llerbee e Newswoman Who Fired e- Networks BY ARTHUR UNGER Public Television nd the Camel's Nose Y BERNARD S. REDMONT V's Distorted and 'ssing Images f Women and e Elderly Y BERT R. BRILLER EVISION BULK RATE Ii lkih.hiid1II1 111 I.III, I,II. III II 1II.I,II U.S. POSTAGE RTERLY xxAUTO.xxx.xxxxxxxxxMIXEO HOC 430 CITY' PAID W. 57TH ST. LINCOLN LIBRARIES REFRENCE DEPT. COLUMBUS, OH YO3K 136 S 14TH ST LINCOLN NE 68508 -1801 PERMIT NO. 2443 . 10019 www.americanradiohistory.com Hubbard Broadcasting'.0 bbarc Proudly d casti nc The National Academy of Television Arts and Sciences P -FM KS KSTP -AM KSTP- V USSB CONUS F&F Productions Inc. Diamond P Sports All News Channel WD1O -TV WIRT -TV KSAX -TV KRWF -TV KOB-TV KOBR-TV KOBFTV WNYT TV WNEC -TV www.americanradiohistory.com Muchas gracias, muchas gracias. As the first Spanish -language television network to be honored with two national Emmy Awards, we thought some words of thanks were in order. "Gracias" to our talented Noticiero Univision team of anchors, reporters, and producers for their award -winning coverage of last summer's devastating Hurricane Mitch. " Gracias" to the National Academy of Television Arts and Sciences for recognizing not just the increasing importance, but the worldclass quality of Spanish- language newscasting in this country. www.americanradiohistory.com e aétte°ate o new ColorStream Pro DVD with Progressive Scan & eue/7,4n ckieectle, Jowni dedyne4e, echto4e, CMdiStAWitt eChjA94e, ca4ne4eaman, aJst'sttan,tt , vi G(.SKIT,G1tct4W, W ¡ re0/ ud10, u1agta eve/7me Jee defix ukO4 de Way aif,W. -

{EIR} Joins Fight Against Cisneros Takeover of U.S. Television Network

Click here for Full Issue of EIR Volume 19, Number 27, July 3, 1992 EIR joins fight against Cisneros takeover of U. S. television network by Carlos Wesley On June 18, EIR editor Nora Hamerman filed a formal letter 18. In a statement issued jointly by the Media Coalition's of objection on behalf of EIR with the Federal Communica chairwoman Esther Renteria from Los Angeles, the Cham tions Commission (FCC) regarding the attempted takeover ber's Dr. Jose Nino, and the Puerto Rican Coalition's Luis of Univision, the largest Spanish-language television net Nunez from Washington, D. C. , they said that the transfer work in the United States, by a group of dirty-money invest poses the danger of illegal "foreign control of U. S. A. broad ors that includes Venezuelan Gustavo Cisneros Rendiles and cast media. " They noted that in 1986, Azcarraga was forced his brother Ricardo. Former Norman Lear partner Jerrold by the FCC to divest himself of many of the same television Perenchio and Mexican media baron Emilio Azcarraga, own stations that today make up the Univision network, "because er of the Televisa network, are the other principals in the of unlawful alien control" of U. S. broadcasting facilities. deal. Now, "Azcarraga is back at the FCC asking to own 12. 5% Azcarraga's Televisa is notorious for its pornographic of these stations, and for a 'friendly' alien ally to own another soap operas and for its roster of avowedly Satan-worshiping 12. 5%, and for them jointly to own 50% of the Univision stars. -

Venezuela's Murdoch

review Pablo Bachelet, Gustavo Cisneros: un empresario global Organización Cisneros: Caracas 2004 and Planeta: Barcelona 2004, €20, hardback 319 pp, 84 08 04958 5 Richard Gott VENEZUELA’S MURDOCH With a fortune of more than $4 billion, Gustavo Cisneros likes to promote the notion of himself as the wealthiest man in Latin America and the most powerful media baron of the continent, a Latino equivalent to Murdoch or Berlusconi. Since 1961 the Organización Cisneros has owned Venevisión, the main commercial tv channel in Venezuela—best known abroad for its rabid opposition to Chávez during the 2002 coup, and ceaseless denunci- ation of his supporters as ‘mobs’ and ‘monkeys’. From the 1980s he has extended his empire across Latin America to include Chile’s Chilevisión and Colombia’s Caracol tv, with a major stake in DirecTV Latin America, whose satellite beams a diet of sport, game-shows, telenovelas and predigested news to twenty Latin American countries. He also has a lucrative share in Univisión, the main Spanish-language channel for the United States, and a joint Latin American internet connection venture with aol-TimeWarner. Like many wealthy Latin Americans, Cisneros is a chameleon when it comes to nationality. Nominally a Venezuelan—he was born in Caracas in 1945, to an entrepreneurial Cuban father and Venezuelan mother—he was educated and served his media apprenticeship in the us. But he is also a citizen of Spain, at the personal request of King Juan Carlos; an American in New York, a Cuban in Miami, and a Dominican in the Dominican Republic, where his pricipal base—the Casa Bonita, close to the La Ramona beach resort—is within a golfer’s swing of the retreats of other billionaires of Cuban extraction, grown rich on the profits of sugar, rum and real estate.