Venezuela's Murdoch

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Start Typing Letter Here

Patricia Phelps de Cisneros Por más de cuatro décadas Patricia Phelps de Cisneros ha sido promotora de la educación y del arte, con un enfoque particular en América Latina. En la década de los setenta estableció, junto con su esposo Gustavo Cisneros, la Fundación Cisneros con sede en Caracas y Nueva York. La misión de la Fundación es contribuir a la educación en América Latina y dar a conocer el patrimonio cultural latinoamericano y sus múltiples contribuciones a la cultura global. La Colección Patricia Phelps de Cisneros, fundada a principios de la década de los noventa, es la principal iniciativa cultural de la Fundación Cisneros. Primeras influencias, trabajo y educación William Henry Phelps (1875-1965), bisabuelo de Patricia Cisneros, emprendió una expedición ornitológica en Venezuela, tras concluir su tercer año de licenciatura en la Universidad de Harvard. En ese viaje se enamoró del país y, al concluir sus estudios, regresó para asentarse permanentemente en el país. Phelps fue el gran emprendedor de su época, desarrollando prácticas modernas de negocios y estableciendo varias compañías, desde emisoras de televisión y estaciones de radio hasta importadoras de automóviles, refrigeradores, victrolas, máquinas de escribir, además que fue pionero en introducir el gusto por el béisbol en el país. Creó también la primera fundación en Venezuela. Su profundo interés por las ciencias naturales lo llevó a convertirse en un notable ornitólogo, a catalogar muchas especies aviarias de Suramérica y a publicar sus descubrimientos junto a su mentor, el científico Frank M. Chapman, en el Museo de Historia Natural de Nueva York (AMNH por sus siglas en inglés). -

ORGANIZATION of AMERICAN STATES Inter-American Commission on Human Rights

ORGANIZATION OF AMERICAN STATES Inter-American Commission on Human Rights Application filed with the Inter-American Court of Human Rights In the case of Luisiana Ríos et al. (Case 12.441) against the Republic of Venezuela DELEGATES: Paulo Sérgio Pinheiro, Commissioner Santiago A. Canton, Executive Secretary Ignacio J. Álvarez, Special Rapporteur for Freedom of Expression ADVISERS: Elizabeth Abi-Mershed Débora Benchoam Lilly Ching Ariel E. Dulitzky Alejandra Gonza Silvia Serrano April 20, 2007 1889 F Street, N.W. Washington, D.C., 20006 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page I. INTRODUCTION....................................................................................................... 1 II. PURPOSE................................................................................................................ 1 III. REPRESENTATION ................................................................................................... 3 IV. JURISDICTION OF THE INTER-AMERICAN COURT........................................................ 3 V. PROCESSING BY THE INTER-AMERICAN COMMISSION ................................................ 3 VI. FACTS...................................................................................................................11 A. The political situation and the context of intimidation of media workers................11 B. The Radio Caracas Televisión (RCTV) Network and employees who are the victims in the instant case..............................................................................13 C. Statements by the President -

Miss Venezuela

Universidad Católica Andrés Bello Facultad de Humanidades y Educación Escuela de Comunicación Social Comunicaciones Integradas al Mercadeo Trabajo Final de Concentración Concursos de belleza como herramienta promocional de la moda. Caso de estudio: Miss Venezuela Autoras: María Valentina Castro Lindainés Romero Tutor: Pedro José Navarro Caracas, julio 2017 INDICE GENERAL Introducción…………………………………………………………………….................3 Capítulo I. Marco Teórico……………………………….………………………………5 1. Marco Conceptual………………………………………………………….….5 1.1 Imagen……………………………………………………………………...5 1.1.1 Definición…………………………………………………………...5 1.1.2 Tipos de Imagen…………………………………………………...5 1.2 Posicionamiento…………………………………………………………...6 1.2.1 Definición…………………………………………………………...6 1.2.2 Estrategias de posicionamiento………………………………….7 1.3 Promoción………………………………………………………………….8 1.3.1 Definición…………………………………………………………...8 1.3.2 Herramientas de la mezcla de promoción………………………9 1.3.3 Medios Convencionales…………………………………………10 1.3.4 Medios no Convencionales……………………………………..11 1.3.5 Origen y Evolución…………………………………………...….12 1.4 Segmentación……………………………..……………………………..12 1.4.1 Definición…………………………….……………………………12 2. Marco Referencial……………………………………………………………14 2.1 Origen de los concursos de belleza……………………………………14 2.2 El primer concurso de belleza………………………………………….14 2.3 Miss Venezuela…………………………………………………………..16 2.3.1 Situación político, social y económica del Miss Venezuela…22 Capítulo 2. Marco Metodológico……………………………………………………..26 1. Modalidad…………………………………………………………………26 1 2. Objetivo……………………………………………………………………26 -

Media Kit 2O15

media kit2O15 1O Reasons to Advertise in TV Latina 1 Editorial Excellence 6 Digital Editions For 19 years, our editorial group has published articles based on exhaustive Your ad will appear in the digital edition of the magazine, which reaches TV Latina media executives before the markets. research, with the journalistic integrity the industry deserves. has set 35,000 the standard for editorial excellence. Our interviews are always unique; unlike others, we do not publish interviews from press conferences or other promo- 7 Annual Guides tional materials. Our company also distributes two yearly guides, Guía de Canales and Guía de Dis- tribuidores, reaching programming executives in the region. Both guides are 3,000 2 The Most Influential Publishing Group distributed at NATPE, as well as various other markets throughout the year. TV Latina is part of World Screen, the most important, influential and respected group in the international media industry. This allows you to expand your target 8 Broad Online Coverage around the world at no additional cost. All printed and online information, includ- We offer our sponsors coverage throughout the year with our online newsletters Diario TV Latina ing content from all three of ’s editors, plus summaries and transla- TV Latina, TV Latina Semanal, TV Canales Semanal, TV Novelas y Series Semanal and tions in English, are done by our team, spearheaded by Anna Carugati, the TV Niños Semanal, which are sent to some executives in the region. Moreover, 9,000 group editorial director, and recipient of an Emmy award for journalism, a our nine English-language services reach an additional executives, pro- 35,000 duPont Columbia honorable mention and the Associated Press award for edit - viding you with a powerful information tool during the entire year. -

Historical Narratives of Denial of Racism And

Historical Narratives of Denial of Racism and the Impact of Hugo Chávez on Racial Discourse in Venezuela Valentina Cano Arcay DEVL 1970: Individual Research Project Prof. Keisha-Khan Perry December 19, 2019 Do not copy, cite, or distribute without permission of the author. / Cano Arcay 2 INDEX INTRODUCTION 3 Structure of the Capstone 10 PART I: NARRATIVES OF DENIAL OF RACISM THROUGHOUT VENEZUELAN HISTORY 11 "Mejorando la Raza": Racism through Miscegenation and Blanqueamiento 12 "Aquí no hay racismo, hay clasismo": The Separation of Race and Class 19 Comparison with the United States 23 Is this Denial True? Examining Forms of Racism in Venezuela 25 Language 26 Perceptions of Racism by Black Venezuelans 26 Media 30 PART II: HUGO CHÁVEZ AND RACIAL DISCOURSE 33 Hugo Chávez's Personal Background and Narrative 35 Policies 37 "El Pueblo" and President Chávez 40 Popular Support for President Chávez 41 The Opposition and President Chávez 42 Limitations and Backlash 43 How Does This All Negate the Historic Denial of Racism? 44 CONCLUSION 46 APPENDIX 50 BIBLIOGRAPHY 52 / Cano Arcay 3 INTRODUCTION On September 20, 2005, President of Venezuela Hugo Chávez Frías, in an interview with journalist Amy Goodman, stated that: "hate against me has a lot to do with racism. Because of my bemba (big mouth), because of my curly hair. And I'm so proud to have this mouth and hair because it's African" (Nzamba). In a country with legacies of slavery and colonialism, it seems evident that, throughout history, politicians would address the topic of racial discrimination. However, this comment by President Chávez was very uncommon for a Venezuelan politician. -

Nationalism, Sovereignty, and Agrarian Politics in Venezuela

Sowing the State: Nationalism, Sovereignty, and Agrarian Politics in Venezuela by Aaron Kappeler A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Anthropology University of Toronto © Copyright by Aaron Kappeler 2015 Sowing the State: Nationalism, Sovereignty and Agrarian Politics in Venezuela Aaron Kappeler Doctor of Philosophy Degree Anthropology University of Toronto 2015 Abstract Sowing the State is an ethnographic account of the remaking of the Venezuelan nation- state at the start of the twenty-first century, which underscores the centrality of agriculture to the re-envisioning of sovereignty. The narrative explores the recent efforts of the Venezuelan government to transform the rural areas of the nation into a model of agriculture capable of feeding its mostly urban population as well as the logics and rationales for this particular reform project. The dissertation explores the subjects, livelihoods, and discourses conceived as the proper basis of sovereignty as well as the intersection of agrarian politics with statecraft. In a nation heavily dependent on the export of oil and the import of food, the politics of land and its various uses is central to statecraft and the rural becomes a contested field for a variety of social groups. Based on extended fieldwork in El Centro Técnico Productivo Socialista Florentino, a state enterprise in the western plains of Venezuela, the narrative analyses the challenges faced by would-be nation builders after decades of neoliberal policy designed to integrate the nation into the global market as well as the activities of the enterprise directed at ii transcending this legacy. -

Thousands Flee Smoke in Iowa City

M - MANCHESTER HERALD. Monday, July 15, 1985 MANCHESTER FOCUS SPORTS WEATHER BUSINESS School board mixed Inexpensive tours Little League stars Clear skies tonight; about abuse program create summer fun lose tourney tilts [some sun Wednesday People, money parted ... page 3 ... page 11 ... page 17 ... page 2 Array of credit cards bombarding consumers Discover combines an array of financial services purchase on your newly authorized card and start A seemingly endless parade of credit cards and features and is a direct result of the ferment in this using the item without any delay at all. variations of them is marching into your wallet — with " I f the customer has good credit, the approval the obvious objective of lessening your desire for '"Th*e'card operates like a general credit card. process can take minutes because of access to major cash, Single-purpose credit cards, such as those Your Owners can use it at participating establishmenU credit bureaus," says Marsh. anywhere. You will pay a cardholder fee and be issued by department stores and oil companies, were 2. In some states, manufacturers offer lower long ago joined by bank cards such as MasterCa rd and Money's charged competitive interest rates. UJaurliFfitfr interest rates than those charged on bank cards. At a ftiii /-M * TiiAoHaw .Liilv. But as a user, you’ll be able to lap into other Manchester, Conn. — A City of Village Charm Tuesday, July 16, 1985 — Single copy; 25<P Visa plus travel and entertainment cards, such as minimum, the rates compete with bank card rates, Worth financial services, including automated teller ma American Express and Diners' Club. -

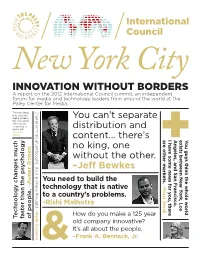

Innovation Without Borders

International Council NewINNOVATION York WITHOUT CityBORDERS A report on the 2012 International Council summit, an independent forum for media and technology leaders from around the world at the Paley Center for Media. Digital isn’t an afterthought, it’s a primary thought. The main thing is to close the digital divide in You can’t separate this new world, either you’re connected or distribution and you’re out. –Ricardo Salinas content... there’s are other markets. other markets. are there you, for some news I have Angeles, and San Francisco. Los York, New between exists think the whole world guys You no king, one without the other. –Jeff Bewkes You need to build the –Yossi Vardi –Yossi –Avner Ronen –Avner technology that is native to a country’s problems. -Rishi Malhotra –Herb Scannell How do you make a 125 year Technology changes much Technology than the psychology faster of people. old company innovative? It’s all about the people. –Frank A. Bennack, Jr. PC_ICBook_FINAL.indd 1 3/18/13 11:07 PM The Innovation Imperative In November 2012, The Paley Center for Media convened the twentieth meeting of the International Council since this perennial gathering of global media leaders began in 1995. Delegates from here in the US to countries in Latin America, Europe, Asia, and the Middle East, assembled at the Paley Center’s New York headquarters and the Time Warner Center for three days of dialogue and debate under the guiding theme “Innovation without Borders.” Certainly, as a longtime convener of international media leaders, The Paley Center has seen that growth goes hand-in-hand with corporate investment and partnerships across borders. -

Media Kit 2O16

TV Latina Mediakit_2016_Layout 1 7/7/15 2:52 PM Page 1 GUÍA DE CANALES 2015 GUÍA DE DISTRIBUIDORES 2015 WWW.TEVEBRASIL.COM JULHO/ AGOSTO 2014 EDIÇÃO ABTA Publicaciones TVBRASIL A hora é esta / Anthony Doyle da Turner TV Latina es una publicación en español que cubre las industrias de programación, cable y satélite en Latinoamérica, / Gustavo Leme da Fox EDICIÓN L.A. SCREENINGS WWW.TVLATINA.TV MAY O 2014 el mercado hispano en Estados Unidos e Iberia. Robert Bakish de Viacom / Elie Dekel de Saban Brands Contenidos digitales paraNIÑOS preescolares / ids Awards TV Peppa Pig Entrega de los International Emmy K Phil Davies y Neville Astley de / WWW.TVLATINA.TV MAYO 2014 TVNOVELASEDICIÓN L.A. SCREENINGS TV Niños es una revista completamente dedicada al negocio de la programación y mercancías infantiles. Novelas y series en plataformas no lineales / Fernando Gaitán TV Novelas es una revista enfocada en las últimas tendencias en este creciente género popular. TV Brasil es la revista dedicada a la cobertura del mercado de televisión brasileño escrita en portugués. La Guía de Canales es una guía portátil anual que provee una mirada completa a la industria de cable y satélite en Latinoamérica. Esta guía se distribuye en siete convenciones durante el año y se envía a ejecutivos en la región. 3 mil La Guía de Distribuidores es una guía portátil anual dedicada exclusivamente al negocio de la distribución de programación en Latinoamérica, el mercado hispano de Estados Unidos e Iberia. La guía está disponible en NATPE y los L.A. Screenings. También se envía a ejecutivos de programación en la región. -

Patricia Phelps De Cisneros

Patricia Phelps de Cisneros For more than four decades, Patricia Phelps de Cisneros has fervently supported education and the arts, with a particular focus on Latin America. In the 1970s, along with her husband, Gustavo A. Cisneros, she founded the New York City and Caracas-based Fundación Cisneros. Its mission is to improve education throughout Latin America and to foster global awareness of the region’s heritage and many contributions to world culture. The Colección Patricia Phelps de Cisneros, founded in the early 1990s, is the primary art-related program of the Fundación Cisneros. Early influences, work, and education Patricia Cisneros’s great-grandfather William Henry Phelps (1875—1965) undertook an ornithological expedition to Venezuela the summer after his junior year at Harvard University. During that trip, he fell in love with the country, and after graduation settled there permanently. Phelps was a great entrepreneur of his era who developed modern business practices and established many companies that ranged from television and radio networks to those that imported automobiles, refrigerators, Victrolas, typewriters, and Venezuela’s first taste of the game of baseball. He also started Venezuela's first foundation. Following his deep interest in natural science, he became a noted ornithologist who catalogued South American bird specimens and published his discoveries alongside his mentor, curator Frank M. Chapman, at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. A supporter as well as a scientific contributor to the AMNH in the following years, Phelps was awarded the position of Research Associate there in 1947. Patricia has credited her great-grandfather’s meticulous attention to the classification of his tropical birds as the inspiration for her awareness of the high level of care and cataloguing needed to preserve a collection and make it available for study. -

Among the Beautiful People

Page 1 of 3 Among the beautiful people November 8 2003 12:00AM The politics may be deadly but in Venezuela gorgeousness is a patriotic duty. Nicholas Griffin meets the ‘Misses’ and the men who remake them Last month I travelled to Caracas, to act as a judge in the Miss Venezuela competition. With 80 per cent of the population watching the pageant on television, Miss Venezuela commands a much greater audience share than any FA Cup Final. In international beauty competition, the country is dominant, having won four Miss Universes, five Miss Worlds and three Miss International titles in the past 24 years. It is said that Venezuela has two great exports: oil and beauty. The former accounts for more than 90 per cent of GDP, but despite this source of wealth half the populace lives in poverty, a legacy of poor government spanning generations. Even with the oil millions at its disposal, the current Chavez administration persists in blaming its failings on private enterprise and imperialism as it tries to force an unwilling nation towards Cuban-style communism. Beauty, on the other hand, is much more accessible to the average Venezuelan. Whether you travel on the subway or walk the finest shopping streets, you will find men and women who care deeply about how they look. It is estimated that 20 per cent of average household income is spent on beauty products and enhancements. With such interest, it is little wonder that winning the Miss Venezuela title is considered a genuine achievement. As a result, competitors in the pageant come from all walks of life, although the 20 entrants who make the final cut are invariably university students. -

Democracy in Venezuela

DEMOCRACY IN VENEZUELA HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON THE WESTERN HEMISPHERE OF THE COMMITTEE ON INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED NINTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION NOVEMBER 17, 2005 Serial No. 109–140 Printed for the use of the Committee on International Relations ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.house.gov/international—relations U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 24–600PDF WASHINGTON : 2006 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2250 Mail: Stop SSOP, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate Mar 21 2002 11:27 Jul 14, 2006 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 F:\WORK\WH\111705\24600.000 HINTREL1 PsN: SHIRL COMMITTEE ON INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS HENRY J. HYDE, Illinois, Chairman JAMES A. LEACH, Iowa TOM LANTOS, California CHRISTOPHER H. SMITH, New Jersey, HOWARD L. BERMAN, California Vice Chairman GARY L. ACKERMAN, New York DAN BURTON, Indiana ENI F.H. FALEOMAVAEGA, American ELTON GALLEGLY, California Samoa ILEANA ROS-LEHTINEN, Florida DONALD M. PAYNE, New Jersey DANA ROHRABACHER, California ROBERT MENENDEZ, New Jersey EDWARD R. ROYCE, California SHERROD BROWN, Ohio PETER T. KING, New York BRAD SHERMAN, California STEVE CHABOT, Ohio ROBERT WEXLER, Florida THOMAS G. TANCREDO, Colorado ELIOT L. ENGEL, New York RON PAUL, Texas WILLIAM D. DELAHUNT, Massachusetts DARRELL ISSA, California GREGORY W. MEEKS, New York JEFF FLAKE, Arizona BARBARA LEE, California JO ANN DAVIS, Virginia JOSEPH CROWLEY, New York MARK GREEN, Wisconsin EARL BLUMENAUER, Oregon JERRY WELLER, Illinois SHELLEY BERKLEY, Nevada MIKE PENCE, Indiana GRACE F.