Security Council Distr.: General 27 April 2011

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spatio-Temporal Analysis of the Impact of Rainfall Dynamics on the Water Resources of the N'zi Watershed in Côte D'ivoire

Spatio-temporal analysis of the impact of rainfall dynamics on the water resources of the N'zi watershed in Côte d'Ivoire ABSTRACT This study aims to analyze impacts of rainfall dynamic on the water resources (surface water and groundwater) of N'zi watershed in Côte d'Ivoire. It justifies use of monthly average climatological data (rainfall, temperature) and hydrometric data of the watershed. The methodology is to interpolate by kriging rainfall, to highlight relationship between the spatial variability of rainfall and the surface water flow, and to evaluate groundwater recharge of fractured aquifers in the watershed. At the end of the study, it appears that the ten-year average rainfall of the N'zi watershed has decreased significantly. From 1233 mm during the decade 1951-1960, it lowered to 1074 mm during the decade 1991-2000. During the decades 1961-1970, 1971-1980 and 1981-1990, average rainfall is estimated at 1213 mm, 1068 mm and 1050 mm, respectively. From a spatial point of view, decrease in rainfall intensity was strongly felt in the central and northern localities, as in those located in the south of the watershed. Evolution of stream flow and rainfall is similar in the upper and middle N'zi, with maximum flow period in september corresponding mainly to the period of high rainfall. However, two peaks of different amplitude and a slight shift are observed between the peaks of rain and those of flow mainly in low N'zi. Water quantity streamed in the N’zi watershed during the period of 1972 to 2000 is of 40.7 mm. -

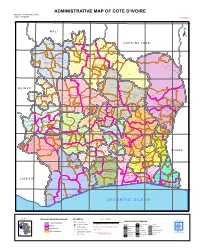

ADMINISTRATIVE MAP of COTE D'ivoire Map Nº: 01-000-June-2005 COTE D'ivoire 2Nd Edition

ADMINISTRATIVE MAP OF COTE D'IVOIRE Map Nº: 01-000-June-2005 COTE D'IVOIRE 2nd Edition 8°0'0"W 7°0'0"W 6°0'0"W 5°0'0"W 4°0'0"W 3°0'0"W 11°0'0"N 11°0'0"N M A L I Papara Débété ! !. Zanasso ! Diamankani ! TENGRELA [! ± San Koronani Kimbirila-Nord ! Toumoukoro Kanakono ! ! ! ! ! !. Ouelli Lomara Ouamélhoro Bolona ! ! Mahandiana-Sokourani Tienko ! ! B U R K I N A F A S O !. Kouban Bougou ! Blésségué ! Sokoro ! Niéllé Tahara Tiogo !. ! ! Katogo Mahalé ! ! ! Solognougo Ouara Diawala Tienny ! Tiorotiérié ! ! !. Kaouara Sananférédougou ! ! Sanhala Sandrégué Nambingué Goulia ! ! ! 10°0'0"N Tindara Minigan !. ! Kaloa !. ! M'Bengué N'dénou !. ! Ouangolodougou 10°0'0"N !. ! Tounvré Baya Fengolo ! ! Poungbé !. Kouto ! Samantiguila Kaniasso Monogo Nakélé ! ! Mamougoula ! !. !. ! Manadoun Kouroumba !.Gbon !.Kasséré Katiali ! ! ! !. Banankoro ! Landiougou Pitiengomon Doropo Dabadougou-Mafélé !. Kolia ! Tougbo Gogo ! Kimbirila Sud Nambonkaha ! ! ! ! Dembasso ! Tiasso DENGUELE REGION ! Samango ! SAVANES REGION ! ! Danoa Ngoloblasso Fononvogo ! Siansoba Taoura ! SODEFEL Varalé ! Nganon ! ! ! Madiani Niofouin Niofouin Gbéléban !. !. Village A Nyamoin !. Dabadougou Sinémentiali ! FERKESSEDOUGOU Téhini ! ! Koni ! Lafokpokaha !. Angai Tiémé ! ! [! Ouango-Fitini ! Lataha !. Village B ! !. Bodonon ! ! Seydougou ODIENNE BOUNDIALI Ponondougou Nangakaha ! ! Sokoro 1 Kokoun [! ! ! M'bengué-Bougou !. ! Séguétiélé ! Nangoukaha Balékaha /" Siempurgo ! ! Village C !. ! ! Koumbala Lingoho ! Bouko Koumbolokoro Nazinékaha Kounzié ! ! KORHOGO Nongotiénékaha Togoniéré ! Sirana -

Emergences Endémiques De Fièvre Jaune Dans La Région

LABORATOIRE D'ENTOMOLOGIE MEDICALE O.R.S.T.O.M. DE L'INSTITUT PASTEUR DE COTE D'IVOIRE O1 BP V-51 Abid.jan O1 O1 BP 490 Abidjan O1 EPERGENCES ENDEMIQUES DE FIEVRE JAUNE DANS LA REGION DE NIAKARAMANDOUGOU REPUBLIQUE DE COTE D'IVOIRE. ENQUETE ENTOMO - EPIDEMIOLOGIQUE -. Roger CORDELLIER Bernard BOUCHITE Dr. es-Sciences Technicien supérieur Entomologiste médical ORSTOM d''Entomologie médicale ORSTOM . c I- 1 1. INTRODUCTION . Le décès le 28 novembre 1982 à l'hôpital de Bouaké, après son trans- fert depuis l'hôpital de Niakaramandougou, d'un Instituteur de 24 ans, a pu être rapporté 2 la fièvre jaune par le Dr. M. LHUILLIER (IgM sur un sé- rumpparvenu seulement le 10 décembre à l'Institut Pasteur). Une enquête conjointe IPCI/ORSTOM a été aussitôt décidée. En ce qui concernc le Laboratoire d'Entomologie médicale, elle s'est inscrite dans le cadre de la mission mensuelle effectuée à Dabakala (Surveillance de la fièvre jaune, de la dengue, et:autres arboviroses humaines dans la zone des sava- nes semi-humides), et ses différentes phases réalisées le 14, le 17 et le 19 décembre, B partir de la station de Dabakala, avec le personnel perma- nent du Laboratoire, et le personnel embauché localement sur la station. Les renseignements obtenus, et les observations faites sur place, 1. B l'hôpital de Niakaramandougou, dès le 14 décembre, nous ont conduit à centrer les prospections sur le village de OUREGUEKAHA (nouveau village), situé à environ 25 Km au sud de Niakaramandougou, et sur ARIKOKAHA, village de l'instituteur décédé, 2' 18 Km au nord. -

République De Cote D'ivoire

R é p u b l i q u e d e C o t e d ' I v o i r e REPUBLIQUE DE COTE D'IVOIRE C a r t e A d m i n i s t r a t i v e Carte N° ADM0001 AFRIQUE OCHA-CI 8°0'0"W 7°0'0"W 6°0'0"W 5°0'0"W 4°0'0"W 3°0'0"W Débété Papara MALI (! Zanasso Diamankani TENGRELA ! BURKINA FASO San Toumoukoro Koronani Kanakono Ouelli (! Kimbirila-Nord Lomara Ouamélhoro Bolona Mahandiana-Sokourani Tienko (! Bougou Sokoro Blésségu é Niéllé (! Tiogo Tahara Katogo Solo gnougo Mahalé Diawala Ouara (! Tiorotiérié Kaouara Tienn y Sandrégué Sanan férédougou Sanhala Nambingué Goulia N ! Tindara N " ( Kalo a " 0 0 ' M'Bengué ' Minigan ! 0 ( 0 ° (! ° 0 N'd énou 0 1 Ouangolodougou 1 SAVANES (! Fengolo Tounvré Baya Kouto Poungb é (! Nakélé Gbon Kasséré SamantiguilaKaniasso Mo nogo (! (! Mamo ugoula (! (! Banankoro Katiali Doropo Manadoun Kouroumba (! Landiougou Kolia (! Pitiengomon Tougbo Gogo Nambonkaha Dabadougou-Mafélé Tiasso Kimbirila Sud Dembasso Ngoloblasso Nganon Danoa Samango Fononvogo Varalé DENGUELE Taoura SODEFEL Siansoba Niofouin Madiani (! Téhini Nyamoin (! (! Koni Sinémentiali FERKESSEDOUGOU Angai Gbéléban Dabadougou (! ! Lafokpokaha Ouango-Fitini (! Bodonon Lataha Nangakaha Tiémé Villag e BSokoro 1 (! BOUNDIALI Ponond ougou Siemp urgo Koumbala ! M'b engué-Bougou (! Seydougou ODIENNE Kokoun Séguétiélé Balékaha (! Villag e C ! Nangou kaha Togoniéré Bouko Kounzié Lingoho Koumbolokoro KORHOGO Nongotiénékaha Koulokaha Pign on ! Nazinékaha Sikolo Diogo Sirana Ouazomon Noguirdo uo Panzaran i Foro Dokaha Pouan Loyérikaha Karakoro Kagbolodougou Odia Dasso ungboho (! Séguélon Tioroniaradougou -

Tortiya, Quand Le Diamant Fait Perdre La Tête

Novembre 2015 Groupe de Recherche et de Plaidoyer sur les Industries Extractives Côte d’Ivoire TORTIYA, QUAND LE DIAMANT FAIT PERDRE LA TÊTE Rapport réalisé pour le GRPIE par Koffi K. Michel Yoboué avec les contributions du Dr José Darrozes, Dr Bernard Elyakime et du Dr Eric Maire Cote d’Ivoire : Tortiya, quand le diamant fait perdre la tête 0 | P a g e Publié en Novembre 2015 par le GRPIE (Groupe de Recherche et de Plaidoyer sur les Industries Extractives) avec Partenariat Afrique Canada (PAC). Toute reproduction, même partielle, doit mentionner le titre et le nom des auteurs mentionnés-ci dessus comme étant les propriétaires des droits d’auteurs. Ce rapport est établi à partir des enquêtes de terrain et de sources jugées fiables par le GRPIE, mais le GRPIE n’est pas responsable de leur exhaustivité. Ce rapport est fourni à titre informatif et à des fins de plaidoyers. Les opinions et informations fournies sont valables à la date d’émission du rapport et sont sujettes à modification. Produit grâce à l’appui de l’Union européenne. © GRPIE et Partenariat Afrique Canada Novembre 2015 Partenariat Afrique Canada 331 Cooper Street, Suite 600 Ottawa, Ontario, K2P 0G5, Canada [email protected] www.pacweb.org Photo de couverture : Lavage de gravier par des exploitants artisanaux de diamant dans la rivière Bou. Crédit : M.Yoboué/ GRPIE 2015. Cote d’Ivoire : Tortiya, quand le diamant fait perdre la tête 1 | P a g e TABLE DES MATIERES INTRODUCTION _______________________________________________________________________ 3 RECOMMANDATIONS __________________________________________________________________ 4 I. TORTIYA, UNE VILLE PAS COMME LES AUTRES ________________________________________ 7 1. -

Côte D'ivoire

AFRICAN DEVELOPMENT FUND PROJECT COMPLETION REPORT HOSPITAL INFRASTRUCTURE REHABILITATION AND BASIC HEALTHCARE SUPPORT REPUBLIC OF COTE D’IVOIRE COUNTRY DEPARTMENT OCDW WEST REGION MARCH-APRIL 2000 SCCD : N.G. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS, WEIGHTS AND MEASUREMENTS ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS, LIST OF ANNEXES, SUMMARY, CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS BASIC DATA AND PROJECT MATRIX i to xii 1 INTRODUCTION 1 2 PROJECT OBJECTIVES AND DESIGN 1 2.1 Project Objectives 1 2.2 Project Description 2 2.3 Project Design 3 3. PROJECT IMPLEMENTATION 3 3.1 Entry into Force and Start-up 3 3.2 Modifications 3 3.3 Implementation Schedule 5 3.4 Quarterly Reports and Accounts Audit 5 3.5 Procurement of Goods and Services 5 3.6 Costs, Sources of Finance and Disbursements 6 4 PROJECT PERFORMANCE AND RESULTS 7 4.1 Operational Performance 7 4.2 Institutional Performance 9 4.3 Performance of Consultants, Contractors and Suppliers 10 5 SOCIAL AND ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT 11 5.1 Social Impact 11 5.2 Environmental Impact 12 6. SUSTAINABILITY 12 6.1 Infrastructure 12 6.2 Equipment Maintenance 12 6.3 Cost Recovery 12 6.4 Health Staff 12 7. BANK’S AND BORROWER’S PERFORMANCE 13 7.1 Bank’s Performance 13 7.2 Borrower’s Performance 13 8. OVERALL PERFORMANCE AND RATING 13 9. CONCLUSIONS, LESSONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS 13 9.1 Conclusions 13 9.2 Lessons 14 9.3 Recommendations 14 Mrs. B. BA (Public Health Expert) and a Consulting Architect prepared this report following their project completion mission in the Republic of Cote d’Ivoire on March-April 2000. -

Cas Du Département De Katiola, Région Des Savanes De Côte D'ivoire

Répartition spatiale, gestion et exploitation des eaux souterraines : cas du département de Katiola, région des savanes de Côte d’Ivoire Talnan Coulibaly To cite this version: Talnan Coulibaly. Répartition spatiale, gestion et exploitation des eaux souterraines : cas du départe- ment de Katiola, région des savanes de Côte d’Ivoire. Sciences de la Terre. Université Paris-Est, 2009. Français. NNT : 2009PEST1034. tel-00638690 HAL Id: tel-00638690 https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-00638690 Submitted on 7 Nov 2011 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Université Paris Est Université d ’Abobo-Adjamé France Côte d ’Ivoire Université Paris Est THÈSE pour obtenir le grade de Docteur de l ’Université de Paris Est Spécialité : Sciences de l ’Information Géographique Présentée et soutenue publiquement par Talnan Jean Honoré COULIBALY le 09 juillet 2009 Répartition spatiale, Gestion et Exploitation des eaux souterraines Cas du département de Katiola, région des savanes de Côte d ’Ivoire Jury : Qualité Nom et Prénoms Grade, Organisme d ’appartenance Lieu d ’exercice label Labo, adresse DEROIN Jean-Paul Professeur, EA 4119 G2I Directeurs de Thèse Univ. Paris-Est Marne la Vallée Univ. Paris-Est Marne la Vallée (France) SAVANE Issiaka Professeur, Géosciences & Environnement Univ. -

Region Hambol.Pdf

REGION DU HAMBOL LOCALITE DEPARTEMENT REGION POPULATION SYNTHESE SYNTHESE SYNTHESE COUVERTURE 2G COUVERTURE 3G COUVERTURE 4G ALLASSO NIAKARAMADOUGOU HAMBOL 306 ANGOLOKAHA NIAKARAMADOUGOU HAMBOL 1208 ARIKOKAHA NIAKARAMADOUGOU HAMBOL 1233 ATTIENKAHA KATIOLA HAMBOL 999 ATTISSA DABAKALA HAMBOL 479 BABADOUGOU DABAKALA HAMBOL 391 BADIKAHA NIAKARAMADOUGOU HAMBOL 4932 BADIOKAHA NIAKARAMADOUGOU HAMBOL 1374 BAKORO SÉOULA DABAKALA HAMBOL 374 BAKORO SOBARA DABAKALA HAMBOL 1139 BALA DABAKALA HAMBOL 692 BALANZIÉ DABAKALA HAMBOL 2039 BAMBARASSO DABAKALA HAMBOL 141 BANGOLO DABAKALA HAMBOL 900 BASSAWA DABAKALA HAMBOL 2033 BESSÉDOUGOU DABAKALA HAMBOL 49 BIDIALA-SOBARA DABAKALA HAMBOL 725 BINDOLO WASSÉGBOGO DABAKALA HAMBOL 780 BOBOSSO DABAKALA HAMBOL 690 BOBOSSO DABAKALA HAMBOL 841 BOGODOUGOU DABAKALA HAMBOL 217 BOKALA NOUMOUSSO DABAKALA HAMBOL 1205 BOKALA-NIAMPONDOUGOU DABAKALA HAMBOL 1688 BONIÉRÉDOUGOU DABAKALA HAMBOL 3002 BOROYARADOUGOU DABAKALA HAMBOL 780 BOUNADOUGOU DABAKALA HAMBOL 1125 REGION DU HAMBOL BROUBROU DIOULASSO DABAKALA HAMBOL 464 BROUBROU SOKOURA DABAKALA HAMBOL 376 DABAKAKRO DABAKALA HAMBOL 1531 DABAKALA DABAKALA HAMBOL 14134 DARAKOKAHA KATIOLA HAMBOL 5966 DARALA DABAKALA HAMBOL 1315 DENDJOUGOUDOUGOU DABAKALA HAMBOL 236 DIAMAKARA DABAKALA HAMBOL 358 DIAMONO DABAKALA HAMBOL 75 DIARADOUGOU DABAKALA HAMBOL 1525 DIEMBRESSÉDOUGOU DABAKALA HAMBOL 1980 DIENGUESSO DABAKALA HAMBOL 1489 DINGASSO DABAKALA HAMBOL 253 DJAKORA DABAKALA HAMBOL 480 DJOLO DABAKALA HAMBOL 318 DOUADIORI DABAKALA HAMBOL 521 DOUSSOULOKAHA NIAKARAMADOUGOU HAMBOL 825 DYENDAGANA -

Côte D'ivoire Living Standards Survey (Cilss) 1985-88

The World Bank/ Institut National de la Statistique, Côte d'Ivoire CôTE D'IVOIRE LIVING STANDARDS SURVEY (CILSS) 1985-88 Basic information for users of the data August 6, 1996 c:\wp51\doc\cilss\cilss3.mv, js Contents I. Introduction .................................................................... 1 II. CILSS Questionnaires ........................................................... 3 The Household Questionnaire ................................................. 3 Community Questionnaire ................................................... 15 The Price Questionnaire ..................................................... 18 Health Facility Survey, 1987 ................................................. 21 III. Sample Design and Selection .................................................... 22 Sampling Procedures for Block 1 Data .......................................... 22 Sampling Procedures for Block 2 Data .......................................... 23 Bias in the Selection of Households within PSUs, Block 1 Data ...................... 23 Problems Due to Inaccurate Estimates of PSU Population ........................... 24 Classification of Clusters by Geographic Location ................................ 24 Non-Response and Replacement of Households ................................... 30 Selection of the Respondent for the Section on Fertility ............................ 31 IV. Survey Organization and Fieldwork .............................................. 32 Field-Testing of the Questionnaires Prior to Survey Implementation .................. -

CÔTE D'ivoire.Ai

vers BOUGOUNI 8° vers BOUGOUNI É 6° vers v. BOBO-DIOULASSO B KOLONDI BA SIKASSO a o g a CÔTE D'IVOIRE u GARALO in b BADOGO l f a é i l n é a k B n B a a K f KADIANA i 4° vers DIÉBOUGOU vers NANDOM n M A L I i BANFORA LAWRA u vers BOLGATANGA MANDIANA o B M HAN g a SINDOU é O g É B U R K I N A Z GOUA U D o MANANKORO é KOUÉRÉ H Tengréla O U É Pogo NIANGOLOKO GAOUA N Kanakoro MISS NI Kimbirila-Nord É ( LOROP NI V vers KANKAN B i Sa Tienko n O n a Niellé a L kar b é a o a T ni ndi É Kaouara o KAMPTI u FOLON ha BAGOU A l a m WA é Sianhala Minignan M Mbengué Diawala o N 10° Goulia K GALGOULI 10° O Barrage de É Kouto Ouangolodougou É I MALINK É É BATI R Farakoungouanan D E N G U L Kasséré MANGODARA E L Samatiguila Gbon ) é Doropo Kaniasso 848 Kolia S A V A N E S r Kimbirila- Bag a LOBI GA Gbéléban Sud oé Niofoin ba G Madinani PORO ï Sinématiali Ouango-Fitini Téhini Varalé a b Tiémé ur a Korhogo o n Seydougou 913 Ferkessédougou Kafolo K h Karakoro a Boundiali É Nassian PARC la Sirana Odienné S NOUFO Séguélon Komborodougou Tioroniaradougou 635 NATIONAL Bouna SOKOURALA 893 KABADOUGOU TCHOLOGO a Sirasso Napié b Guiembé c DIOULA DE LA C C n HA HE Bako m a e 824 l Kong G U I N É E i Dikodougou B T COMOÉ a BOUNKANI 1009 Morondo m Tafiré BOLE Dioulatiédougou a u d È vers BANDA NKWANTA S NKO Dianra o KOULANGO Booko n g 560 a a in o Djibrosso B 643 r Mont B Tortiya I B HAMBOL Boutourou BEYLA Borotou ou Tagadi WORODOUGOU Foumbolo Kotouba rédougo Koro Niakaramandougou Gansé Fé uba W O R BO B A a É Kani n Sarhala V A L L E D U B A N D A M A Z A N Z A N É -

Côte D'ivoire Administrative Map UNHCR, Global Insight Digital Mapping © 1998 Europa Technologies Ltd

FF II CC SS SS Field Information and Coordination Support Section Sources: Côte d'Ivoire Administrative Map UNHCR, Global Insight digital mapping © 1998 Europa Technologies Ltd. UNJLC - UNSDI-T As of November 2010 The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. Cote_Ivoire_Admin_A3PC.WOR ((( BougouniBougouni FaragouaranFaragouaran ((( SikassoSikasso Bobo-Dioulasso ((( ((( Orodara MALI ((( ((( Diébougou LoulouniLoulouni BURKINA FASO T KadianaKadiana ((( ((( Banfora ((( Lawra ZegouaZegoua ManankoroManankoro TENGRELATENGRELATENGRELATingrela ZegouaZegoua Kanakono ((( Gaoua MisséniMisséni ((( Tienko ((( Niangoloko Nielle Minignan Goulia M'bengue ((( Kouto Ouangolodougou Wa ((( Diawala Gbon Kaniasso Samatiguila Kolia Kassere Tehini Dropo Madinani Ferkessedougou Odienne Korhogo BOUNDIALI Tieme BOUNDIALIBOUNDIALI SAVANESSAVANES Niofoin ((( Seydougou Sinematiali ((( FERKESSEDOUGOUFERKESSEDOUGOUFERKESSEDOUGOU ((( Boundiali ((( KorhogoKorhogo FERKESSEDOUGOUFERKESSEDOUGOUFERKESSEDOUGOU ((( OdiennéOdienné KorhogoKorhogo OdiennéOdienné KORHOGOKORHOGO Karakoro ((( Koumbala DENGUELEDENGUELE Boundiali Tioroniaradougou Komborodougou ODIENNEODIENNE Kérouané Seguelon ((( Bouna Guiembe Tafiere Kong Bouna LainéLainé Dioulatiedougou Sirasso Bako Dianra BoleBole Napieoledougou BOUNABOUNA Booko Morondo Djibrosso Niakarmadougou Dikodougou ((( Tortiya Foumbolo ((( KATIOLAKATIOLA GUINEA Borotou Koro Kani Dabakala ZANZANZANZAN TOUBATOUBATOUBA Sarhala BAFINGBAFING CÔTE -

1333118154Nouveau Decoupag

REPUBLIQUE DE COTE D'IVOIRE Union - Discipline - Travail CARTE ADMINISTRATIVE 8°0'0"W 7°0'0"W 6°0'0"W 5°0'0"W 4°0'0"W 3°0'0"W ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Papara ! ! ! ! M A L I (! (! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Débété ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !(! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! TENGRELA !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Kimbirila-Nord Kanakono ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ( ! Toumoukoro ! ! ! ! ! (! ! ! (! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! BURKINA-FASO ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! (! ! ! ! ! (! Mahandiana-Sokourani ! (! ! ! Sokoro ! ! Niellé (! ! ! ! ! ! ! Tienko ! ! ! ! (! ! Blességué Bougou (! ! ! ! ! ! ! (! ! ! Diawala ! ! ! Katogo Kaouara ! ! (! ! ! F O L O N (! ! ! ! Goulia ! 10°0'0"N ! (! MINIGNAN )!(! (! Sianhala M'Bengué ! ! (! ! ! OUANGOLODOUGOU ! ! ! 10°0'0"N !(! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Baya ! (! ! KOUTO ! ! ! ! (! ! ! Fengolo ! ! ! (! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! KANIASSO ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! (! (! (! ! ! Gbon ! ! SAMATIGUILA ! (! ! (! ! ! ! ! ! ! Kasséré (! ! ! (! Katiali TCHOLOGO !(! ! Gogo ! ! Kalamon ! ! ! ! ! ! (! (! ! ! ! Kolia ! DOROPO ! N'Goloblasso ! ! (! ! ! ! ! µ ! ! Tougbo ! (! ! (! Kimbirila-Sud ! ! ! Samango ! ! ! ! ! (! ! SAVANES ! ! ! ! Danoa ! ! (! Gbéléban (! ! TEHINI Niamoué ! SINEMATIALI FERKESSEDOUGOU ! ! (! Niofoin Koni ! ! (! Tiémé ! (! ! (! ! (! (! Lataha !(! )! ! ! (! MADINANI Siempurgo ! (! ! (! ! J! Gbalèkaha (! (! ! Seydougou ! )! (! (Sédiogo) (! ! ! ! KORHOGO (! Togoniéré Bouko ! ODIENNE BOUNDIALI P O R O Koumbala ! (! ! ! ! ! ! ! !( ! J (! Sikolo