How False Were the Strings in Carrickfergus for Louis Macneice?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Recreation Guide

RECREATION GUIDE GO EXPLORE Permit No. 70217 Based upon the Ordnance Survey of Northern Ireland Map with the permission of the controller of her Majesty’s Stationery Office © Crown Copyright 2007 A STRIKING VISUAL BOUNDARY The Belfast Hills make up the summits of the west and north of Belfast city. They form a striking visual boundary that sets them apart from the urban populace living in the valley below. The closeness to such a large population means the hills are becoming increasingly popular among people eager to access them for recreational activities. The public sites that are found across the hills certainly offer fantastic opportunities for organised and informal recreation. The Belfast Hills Partnership was formed in 2004 by a wide range of interest groups seeking to encourage better management of the hills in the face of illegal waste, degradation of landscape and unmanaged access. Our role in recreation is to work with our partners to improve facilities and promote sustainable use of the hills - sensitive to traditional ways of farming and land management in what is a truly outstanding environment. Over the coming years we will work in partnership with those who farm, manage or enjoy the hills to develop recreation in ways which will sustain all of these uses. 4 Belfast Hills • Introduction ACTIVITIES Walking 6 Cycling 10 Running 12 Geocaching 14 Orienteering 16 Other Activities 18 Access Code 20 Maps 21 Belfast Hills • Introduction 5 With well over half a million hikes taken every year, walking is the number one recreational activity in the Belfast Hills. A wide range of paths and routes are available - from a virtually flat 400 metres path at Carnmoney Hill pond, to the Divis Boundary route stretching almost seven miles (11km) across blanket bog and upland heath with elevations of 263m to 377m high. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses 'A forest of intertextuality' : the poetry of Derek Mahon Burton, Brian How to cite: Burton, Brian (2004) 'A forest of intertextuality' : the poetry of Derek Mahon, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/1271/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk "A Forest of Intertextuality": The Poetry of Derek Mahon Brian Burton A copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without his prior written consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged. Submitted as a thesis for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Durham Department of English Studies 2004 1 1 JAN 2u05 I Contents Contents I Declaration 111 Note on the Text IV List of Abbreviations V Introduction 1 1. 'Death and the Sun': Mahon and Camus 1.1 'Death and the Sun' 29 1.2 Silence and Ethics 43 1.3 'Preface to a Love Poem' 51 1.4 The Terminal Democracy 59 1.5 The Mediterranean 67 1.6 'As God is my Judge' 83 2. -

Austin Clarke Papers

Leabharlann Náisiúnta na hÉireann National Library of Ireland Collection List No. 83 Austin Clarke Papers (MSS 38,651-38,708) (Accession no. 5615) Correspondence, drafts of poetry, plays and prose, broadcast scripts, notebooks, press cuttings and miscellanea related to Austin Clarke and Joseph Campbell Compiled by Dr Mary Shine Thompson 2003 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 7 Abbreviations 7 The Papers 7 Austin Clarke 8 I Correspendence 11 I.i Letters to Clarke 12 I.i.1 Names beginning with “A” 12 I.i.1.A General 12 I.i.1.B Abbey Theatre 13 I.i.1.C AE (George Russell) 13 I.i.1.D Andrew Melrose, Publishers 13 I.i.1.E American Irish Foundation 13 I.i.1.F Arena (Periodical) 13 I.i.1.G Ariel (Periodical) 13 I.i.1.H Arts Council of Ireland 14 I.i.2 Names beginning with “B” 14 I.i.2.A General 14 I.i.2.B John Betjeman 15 I.i.2.C Gordon Bottomley 16 I.i.2.D British Broadcasting Corporation 17 I.i.2.E British Council 17 I.i.2.F Hubert and Peggy Butler 17 I.i.3 Names beginning with “C” 17 I.i.3.A General 17 I.i.3.B Cahill and Company 20 I.i.3.C Joseph Campbell 20 I.i.3.D David H. Charles, solicitor 20 I.i.3.E Richard Church 20 I.i.3.F Padraic Colum 21 I.i.3.G Maurice Craig 21 I.i.3.H Curtis Brown, publisher 21 I.i.4 Names beginning with “D” 21 I.i.4.A General 21 I.i.4.B Leslie Daiken 23 I.i.4.C Aodh De Blacam 24 I.i.4.D Decca Record Company 24 I.i.4.E Alan Denson 24 I.i.4.F Dolmen Press 24 I.i.5 Names beginning with “E” 25 I.i.6 Names beginning with “F” 26 I.i.6.A General 26 I.i.6.B Padraic Fallon 28 2 I.i.6.C Robert Farren 28 I.i.6.D Frank Hollings Rare Books 29 I.i.7 Names beginning with “G” 29 I.i.7.A General 29 I.i.7.B George Allen and Unwin 31 I.i.7.C Monk Gibbon 32 I.i.8 Names beginning with “H” 32 I.i.8.A General 32 I.i.8.B Seamus Heaney 35 I.i.8.C John Hewitt 35 I.i.8.D F.R. -

"The Given Note": Traditional Music and Modern Irish Poetry

Provided by the author(s) and NUI Galway in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite the published version when available. Title "The Given Note": traditional music and modern Irish poetry Author(s) Crosson, Seán Publication Date 2008 Publication Crosson, Seán. (2008). "The Given Note": Traditional Music Information and Modern Irish Poetry, by Seán Crosson. Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars Publishing. Publisher Cambridge Scholars Publishing Link to publisher's http://www.cambridgescholars.com/the-given-note-25 version Item record http://hdl.handle.net/10379/6060 Downloaded 2021-09-26T13:34:31Z Some rights reserved. For more information, please see the item record link above. "The Given Note" "The Given Note": Traditional Music and Modern Irish Poetry By Seán Crosson Cambridge Scholars Publishing "The Given Note": Traditional Music and Modern Irish Poetry, by Seán Crosson This book first published 2008 by Cambridge Scholars Publishing 15 Angerton Gardens, Newcastle, NE5 2JA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2008 by Seán Crosson All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-84718-569-X, ISBN (13): 9781847185693 Do m’Athair agus mo Mháthair TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements ................................................................................. -

ACTA UNI VERSITATIS LODZIENSIS David Gilligan ONCE ALIEN HERE

ACTA UNI VERSITATIS LODZIENSIS FOLIA LITTER ARIA ANGLICA 4, 2000 David Gilligan University of Łódź ONCE ALIEN HERE: THE POETRY OF JOHN HEWITT John Hewitt, who died in 1987 at the age of 80 years, has been described as the “elder statesman” of Ulster poetry. He began writing poetry in the 1920s but did not appear in book form until 1948; his final collection appearing in 1986. However, as Frank Ormsby points out in the 1991 edition of Poets From The North of Ireland, recognition for Hewitt came late in life and he enjoyed more homage and attention in his final years than for most of his creative life. In that respect he is not unlike Poland’s latest Nobel Prize winner in literature. His status was further recognized by the founding of the John Hewitt International Summer School in 1988. It is somewhat strange that such a prominent and central figure in Northern Irish poetry should at the same time be characterised in his verse as a resident alien, isolated and marginalised by the very society he sought to encapsulate and represent in verse. But then Northern Ireland/Ulster is and was a strange place for a poet to flourish within. In relation to the rest of the United Kingdom it was always something of a fossilised region which had more than its share of outdated thought patterns, language, social and political behaviour. Though ostensibly a parliamentary democracy it was a de-facto, one-party, statelet with its own semi-colonial institutions; every member of the executive of the ruling Unionist government was a member of a semi-secret masonic movement (The Orange Order) and amongst those most strongly opposed to the state there was a similar network of semi-secret societies (from the I.R.A. -

Macneice Thesis

UNIVERZITA PALACKÉHO V OLOMOUCI Filozofická fakulta Katedra anglistiky a amerikanistiky BAKALÁŘSKÁ PRÁCE The Main Themes in Louis MacNeice’s Poetry between the Years 1937-1945 Olomouc 2016 Lada Smejkalová Vedoucí bakalářské práce: Mgr. David Livingstone, Ph. D. I declare that I worked on this thesis on my own and I provided all the cited bibliography. ………………………………. 2 I would like to thank my supervisor, Mgr. David Livingstone, Ph.D. for his professional advice. 3 Abstract The aim of this thesis is the analyze the selected poems by Louis MacNeice, a British poet born in Northern Ireland, and find typical repeating themes in them that would characterize the poet’s work. The poems selected for this analysis were all written between the years 1937 and 1945. The main topics discussed are, therefore, the emotional impact of the Second World War for many in Britain, and the resonance of historical places connected with the poet’s life. The very salient theme of human individuality is discussed in this work, and MacNeice’s writing style is compared with the style of his contemporaries (mainly W. H. Auden). The conclusion of the thesis is that the themes appearing in the works of Louis MacNeice, of the connection of individuals with the effects of the war, and of the nature of empathy as a result of personal tragedy, demonstrate much that was shared in British culture and people between the years 1937-1945. In addition, the poet’s style is common with the style of the other poets from the Auden Group. The first part of the thesis is theoretical – an introduction and a short description of the poet's life and places that were important for him and that appear in his work. -

Mackay 2015 Celticism Bookc

‘From Optik to Haptik’: Celticism, symbols and stones in the 1930s Peter Mackay Date of deposit 30/11/2015 Document version Author’s accepted manuscript Access rights © Cambridge University Press 2019. This work has been made available online in accordance with the publisher’s policies. This is the author created accepted version manuscript following peer review and as such may differ slightly from the final published version. Citation for Mackay, P. (2018). ‘From Optik to Haptik’: Celticism, symbols and published version stones in the 1930s. In C. Ferrall, & D. McNeill (Eds.), British Literature in Transition, 1920-1940: Futility and Anarchy (pp. 275-290). (British Literature in Transition). Cambridge University Press. Link to published https://doi.org/10.1017/9781316535929.020 version Full metadata for this item is available in St Andrews Research Repository at: https://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/ ‘From Optik to Haptik’: Celticism, Symbols and Stones in the 1930s I Hugh MacDiarmid’s ‘The Stone Called Saxagonus’, first published in his travel guide-cum-polemic-cum-potboiler The Islands of Scotland (1939), is blunt in its response to the Celtic Twilight: ‘Mrs. Kennedy-Fraser’s Hebridean songs – the whole / Celtic Twilight business – I abhor’.1 This abhorrence is no surprise. By the 1930s, as John Kerrigan has pointed out, ‘[r]ejecting the Celtic Twilight was almost a convention in itself’, and the terms of the rejection were also ‘conventional’.2 Common targets were the perceived sentimentality, imprecision and intellectual -

Eavan Boland

Rejecting Images of Women as “Metaphors and Invocations, Similes and Muses”: Irish Woman Poet Eavan Boland By Kristin Kallaher ’04 Conboy, Katie. “Revisionist Cartography: The Politics of Place in Boland and Heaney.” Border Crossings: Irish Women Writers and National Identities. Ed. Kathryn Kirkpatrick. Tuscaloosa: The University of Alabama Press, 2000. # of Women vs. Men in Some Contemporary Anthologies • 5 of 49. Anthony Bradley’s “new and revised” edition of Contemporary Irish Poetry (1988) • 4 of 35. Fallon and Mahon’s The Penguin Book of Contemporary Irish Poetry (1990). • Zero. Thomas Kinsella’s The New Oxford Book of Irish Verse (19th and 20th century sections) (1989). Deane, Seamus. A Short History of Irish Literature. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 1986. • Section on contemporary Irish poetry mentions: • Louis MacNeice, Austin Clarke, Patrick Kavanagh, Thomas Kinsella, Richard Murphy, Seamus Heaney . • “There is no point in pretending that this summary would serve as a rudimentary history of modern Irish poetry. Too many poets have been omitted…” • He names ten names, including Eavan Boland, and then says . • “The general pattern, although subject to severe modifications in relation to any one of these [younger] poets, is nevertheless established.” Object Lessons: The Life of the Woman and the Poet in Our Time by Eavan Boland • “By luck, or by its absence, I had been born in a country where and at a time when the word woman and the word poet inhabited two separate kingdoms of experience and expression. I could not, it seemed, live in both. As the author of poems I was an equal partner in Irish poetry. -

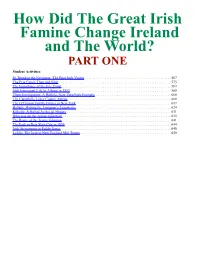

How Did the Great Irish Famine Change Ireland and the World? PART ONE Student Activities: St

How Did The Great Irish Famine Change Ireland and The World? PART ONE Student Activities: St. Brendan the Navigator: The First Irish Visitor . 567 The Erie Canal: Then and Now . 575 The Importance of the Erie Canal. 583 Irish Immigrant Life in Albany in 1852 . 589 Chain Immigration: A Buffalo, New York/Irish Example . 600 The Campbells Leave County Antrim . 609 The O’Connor Family Comes to New York . 617 Ballads: Writing the Emigrant’s Experience. 624 Kilkelly: A Ballad As Social History . 631 Who was on the Jeanie Johnston? . 635 The Route of the Jeanie Johnston. 641 The Irish in New York City in 1855 . 644 Irish Stereotypes in Paddy Songs . 648 Lyddie: The Irish in New England Mill Towns . 659 St. Brendan the Navigator: The First Irish Visitor BACKGROUND t. Brendan is considered to be the first Irish visitor to North America. He was born in Ireland around 489. Some say he was born near Tralee; others say he was born near Killarney. St. Brendan became a Smonk. In the 6th century, many Irish monks were traveling to Europe to establish monasteries as centers of study. They traveled also to lonely islands where they could live close to nature. Legend tells us that St. Brendan and 17 companions left Ireland in an open, leather-covered boat for a voyage of seven years in the North Atlantic, looking for a promised land. It brought them to strange, new lands where they had marvelous adventures. RESOURCES HANDOUTS St. Brendan’s Voyage St. Brendan and His Companions Tim Severin Recreating the Voyage of St. -

'More Than Glass': Louis Macneice's Poetics of Expansion

THE CATHOLIC UNIVERSITY OF AMERICA ‘More than glass’: Louis MacNeice’s Poetics of Expansion A DISSERTATION Submitted to the Faculty of the Department of English School of Arts & Sciences Of The Catholic University of America In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree Doctor of Philosophy © Copyright All Rights Reserved By Michael A. Moir, Jr. Washington, DC 2012 ‘More than glass’: Louis MacNeice’s Poetics of Expansion Michael A. Moir, Jr., PhD Director: Virgil Nemoianu, PhD The Northern Irish poet and dramatist Louis MacNeice, typically regarded as a minor modernist following in the footsteps of Yeats and Eliot or living in the shadow of Auden, is different from his most important predecessors and contemporaries in the way he attempts to explode conventional ideas of place, presenting human subjects in transit and shifting, melting landscapes, rooms and buildings that tend to blend in with their sur- roundings. While Yeats, Eliot and Auden evince a siege mentality that leads them to build religious or political Utopias easily separable from the chaos of the contemporary world, MacNeice denies the validity of any such imaginary constructs, instead taking apart the boundaries of imaginary private worlds, from rooms to islands to pastoral landscapes. Mac- Neice’s representations of space favor what Fredric Jameson terms ‘postmodern space’: his poems and radio plays operate outside of ideas of ‘home,’ ‘church,’ or ‘nation,’ opposing the rigidity of such places to the fluidity of travel. MacNeice has been much misunderstood and underestimated, and a reappraisal of his career is due, particularly given the amount of material that has been published or reis- sued since his centenary in 2007. -

The Cambridge Companion to Irish Poets Edited by Gerald Dawe Frontmatter More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-42035-8 — The Cambridge Companion to Irish Poets Edited by Gerald Dawe Frontmatter More Information the cambridge companion to irish poets The Cambridge Companion to Irish Poets offers a fascinating introduction to Irish poetry from the seventeenth century to the present. Aimed primarily at lovers of poetry, it examines a wide range of poets, including household names, such as Jonathan Swift, Thomas Moore, W. B. Yeats, Samuel Beckett, Seamus Heaney, Patrick Kavanagh, Eavan Boland, and Paul Muldoon. The book is comprised of thirty chapters written by critics, leading scholars and poets, who bring an authoritative and accessible understanding to their subjects. Each chapter gives an overview of a poet’s work and guides the general reader through the wider cultural, historical and comparative contexts. Exploring the dual traditions of English and Irish-speaking poets, this Companion represents the very best of Irish poetry for a general audience and highlights understanding that reveals, in clear and accessible prose, the achievement of Irish poetry in a global context. It is a book that will help and guide general readers through the many achievements of Irish poets. GERALD DAWE is Professor of English and Fellow of Trinity College Dublin. A distinguished poet, he has published eight collections of poetry with The Gallery Press, including, most recently, Selected Poems (2012) and Mickey Finn’s Air (2014). He has also published several volumes of literary essays, and has edited various anthologies, including Earth Voices Whispering: Irish War poetry, 1914–1945 (2008). A complete list of books in the series is at the back of this book. -

MACNEICE, LOUIS. Louis Macneice Collection, 1926-1959

MACNEICE, LOUIS. Louis MacNeice collection, 1926-1959 Emory University Robert W. Woodruff Library Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library Atlanta, GA 30322 404-727-6887 [email protected] Descriptive Summary Creator: MacNeice, Louis. Title: Louis MacNeice collection, 1926-1959 Call Number: Manuscript Collection No. 948 Extent: .25 linear ft. (1 box) Abstract: Small collection of letters from Louis MacNeice to various friends and colleagues from 1926-1959. Language: Materials entirely in English. Administrative Information Restrictions on access Unrestricted access. Terms Governing Use and Reproduction All requests subject to limitations noted in departmental policies on reproduction. Source Purchased from various sources. Citation [after identification of item(s)], Louis MacNeice collection, Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library, Emory University. Processing Processed by Katie Long, July 2003. This finding aid may include language that is offensive or harmful. Please refer to the Rose Library's harmful language statement for more information about why such language may appear and ongoing efforts to remediate racist, ableist, sexist, homophobic, euphemistic and other oppressive language. If you are concerned about language used in this finding aid, please contact us at [email protected]. Emory Libraries provides copies of its finding aids for use only in research and private study. Copies supplied may not be copied for others or otherwise distributed without prior consent of the holding repository. Louis MacNeice collection, 1926-1959 Manuscript Collection No. 948 Collection Description Biographical Note Louis MacNeice was born in Belfast, Ireland in 1907, his family later moved to Carrickfergus, County Antrim. He attended Merton College, Oxford University, 1926-1930, where he met his lifelong friend W.H.