ABSTRACT Title of Document: EROTIC TRANSGRESSION

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Graham Greene Exhibition Catalogue

The Cherry Record Collection of Josephine Reid’s Papers and Books Relating to Our thanks to the following donors who made the acquisition possible: Paul Almond (1949) GRAHAM GREENE Professor John Stephenson (1953) Professor John-Christopher Spender (1957) Roger Jefferies (1957) Paul Lewis (1958) Peter Buckman (1959) Matthew Nimetz (1960) Doug Rosenthal (1961) Alan James (1962) Stephen Crew (1964) Jim Rogers (1964) Emeritus Professor Paul Crittenden (1965) Alan Heeks (1966) Geoff Wright (1967) Neil Record (1972) Julie Record Richard Jones (1977) Mark Storey (1981) Danny Truell (1982) Alison Roberts (1984) Claire Foster-Gilbert (1984) Virginia Preston (1985) Richard Locke (1985) Jonathan Lewin (1992) Adam Dixon (1994) Sarah Longair (1998) Jo Valentine (2001) Jeff Kulkarni (2001) Sean McDaniel (2002) Alice McDaniel (2003) Blackwell Charitable Trust Friends of the National Libraries ISBN 978-1-78280-500-7 An exhibition held at BALLIOL COLLEGE HISTORIC COLLECTIONS CENTRE 9 781782 805007 > ST CROSS CHURCH, ST CROSS ROAD, OXFORD 25 & 26 April 2015 EXHIBITION AND CATALOGUE BY Naomi Tiley Librarian, Balliol College Anna Sander Archivist, Balliol College FOREWORD BY Sir Anthony Kenny Master of Balliol College 1978–1989 Seamus Perry COVER ILLUSTRATIONS: Fellow Librarian, Balliol College Studio portrait of Josephine Reid taken in the late 1940s or early Neil Record 1950s. Photographer unknown. Balliol 1972 Handwriting © Josephine Reid’s Estate Details from postcards from Graham Greene to Josephine Reid © Verdant SA. The organisers are indebted to -

'Bishop Blougram's Apology', Lines 39~04. Quoted in a Sort of Life (Penguin Edn, 1974), P

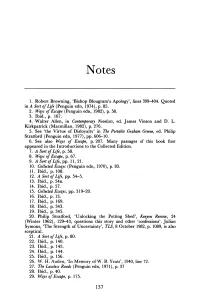

Notes 1. Robert Browning, 'Bishop Blougram's Apology', lines 39~04. Quoted in A Sort of Life (Penguin edn, 1974), p. 85. 2. Wqys of Escape (Penguin edn, 1982), p. 58. 3. Ibid., p. 167. 4. Walter Allen, in Contemporary Novelists, ed. James Vinson and D. L. Kirkpatrick (Macmillan, 1982), p. 276. 5. See 'the Virtue of Disloyalty' in The Portable Graham Greene, ed. Philip Stratford (Penguin edn, 1977), pp. 606-10. 6. See also Ways of Escape, p. 207. Many passages of this book first appeared in the Introductions to the Collected Edition. 7. A Sort of Life, p. 58. 8. Ways of Escape, p. 67. 9. A Sort of Life, pp. 11, 21. 10. Collected Essays (Penguin edn, 1970), p. 83. 11. Ibid., p. 108. 12. A Sort of Life, pp. 54-5. 13. Ibid., p. 54n. 14. Ibid., p. 57. 15. Collected Essays, pp. 319-20. 16. Ibid., p. 13. 17. Ibid., p. 169. 18. Ibid., p. 343. 19. Ibid., p. 345. 20. Philip Stratford, 'Unlocking the Potting Shed', KeT!Jon Review, 24 (Winter 1962), 129-43, questions this story and other 'confessions'. Julian Symons, 'The Strength of Uncertainty', TLS, 8 October 1982, p. 1089, is also sceptical. 21. A Sort of Life, p. 80. 22. Ibid., p. 140. 23. Ibid., p. 145. 24. Ibid., p. 144. 25. Ibid., p. 156. 26. W. H. Auden, 'In Memory ofW. B. Yeats', 1940, line 72. 27. The Lawless Roads (Penguin edn, 1971), p. 37 28. Ibid., p. 40. 29. Ways of Escape, p. 175. 137 138 Notes 30. Ibid., p. -

Norman Macleod

Norman Macleod "This strange, rather sad story": The Reflexive Design of Graham Greene's The Third Man. The circumstances surrounding the genesis and composition of Gra ham Greene's The Third Man ( 1950) have recently been recalled by Judy Adamson and Philip Stratford, in an essay1 largely devoted to characterizing some quite unwarranted editorial emendations which differentiate the earliest American editions from British (and other textually sound) versions of The Third Man. It turns out that these are changes which had the effect of giving the American reader a text which (for whatever reasons, possibly political) presented the Ameri can and Russian occupation forces in Vienna, and the central charac ter of Harry Lime, and his dishonourable deeds and connections, in a blander, softer light than Greene could ever have intended; indeed, according to Adamson and Stratford, Greene did not "know of the extensive changes made to his story in the American book and now claims to be 'horrified' by them"2 • Such obscurely purposeful editorial meddlings are perhaps the kind of thing that the textual and creative history of The Third Man could have led us to expect: they can be placed alongside other more official changes (usually introduced with Greene's approval and frequently of his own doing) which befell the original tale in its transposition from idea-resuscitated-from-old notebook to story to treatment to script to finished film. Adamson and Stratford show that these approved and 'official' changes involved revisions both of dramatis personae and of plot, and that they were often introduced for good artistic or practical reasons. -

Parodying the Politics of Knowledge

Authors of Truth Writers, Liars, and Spies in Our Man In Havana Jacob Carroll “It takes two to keep something real” - Mr. Wormold in Graham Greene’s Our Man In Havana, 103 - Graham Greene’s celebrated parody of the spy-genre Our Man In Havana opens with a comparison between two characters that are completely unknown to the reader: “‘That nigger1 going down the street,’ said Dr. Hasselbacher standing in the Wonder Bar ‘he reminds me of you, Mr. Wormold’” (7). At first, the reader has no way of evaluating the truthfulness of the similarities Dr. Hasselbacher supposedly sees between Mr. Wormold and the “nigger”: these are two characters that have not yet been described except by the comparison in question. Dr. Hasselbacher’s words assert themselves in the mind of the reader as a statement that – however disorienting it may be as an introduction – cannot be immediately disproved or denied. The accuracy of Dr. Hasselbacher’s comparison is first called into question when the two characters are described in more detail by the narrator: the “nigger” is revealed to be a blind beggar with a limp, while Wormold is revealed to be the clean-cut owner of a Havana vacuum-cleaner shop. However, as the novel’s opening speaker, Dr. Hasselbacher initially details for the reader what the reader cannot perceive otherwise; he offers the only representation of Wormold and the “nigger” available at that juncture. The reader cannot evaluate Dr. Hasselbacher’s comparison as either true or false without first accepting it as a possible representation of both Wormold and the “nigger.” Because the comparison cannot be immediately disproved, it becomes a foil that will re-surface again and again as a potentially true description of these characters’ real natures and qualities. -

Cervantes and the Spanish Baroque Aesthetics in the Novels of Graham Greene

TESIS DOCTORAL Título Cervantes and the spanish baroque aesthetics in the novels of Graham Greene Autor/es Ismael Ibáñez Rosales Director/es Carlos Villar Flor Facultad Facultad de Letras y de la Educación Titulación Departamento Filologías Modernas Curso Académico Cervantes and the spanish baroque aesthetics in the novels of Graham Greene, tesis doctoral de Ismael Ibáñez Rosales, dirigida por Carlos Villar Flor (publicada por la Universidad de La Rioja), se difunde bajo una Licencia Creative Commons Reconocimiento-NoComercial-SinObraDerivada 3.0 Unported. Permisos que vayan más allá de lo cubierto por esta licencia pueden solicitarse a los titulares del copyright. © El autor © Universidad de La Rioja, Servicio de Publicaciones, 2016 publicaciones.unirioja.es E-mail: [email protected] CERVANTES AND THE SPANISH BAROQUE AESTHETICS IN THE NOVELS OF GRAHAM GREENE By Ismael Ibáñez Rosales Supervised by Carlos Villar Flor Ph.D A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy At University of La Rioja, Spain. 2015 Ibáñez-Rosales 2 Ibáñez-Rosales CONTENTS Abbreviations ………………………………………………………………………….......5 INTRODUCTION ...…………………………………………………………...….7 METHODOLOGY AND STRUCTURE………………………………….……..12 STATE OF THE ART ..……….………………………………………………...31 PART I: SPAIN, CATHOLICISM AND THE ORIGIN OF THE MODERN (CATHOLIC) NOVEL………………………………………38 I.1 A CATHOLIC NOVEL?......................................................................39 I.2 ENGLISH CATHOLICISM………………………………………….58 I.3 THE ORIGIN OF THE MODERN -

Introduction

Notes INTRODUCTION 1. Graham Greene (ed.), The Old School (London: Jonathan Cape, 1934) 7-8. (Hereafter OS.) 2. Ibid., 105, 17. 3. Graham Greene, A Sort of Life (London: Bodley Head, 1971) 72. (Hereafter SL.) 4. OS, 256. 5. George Orwell, The Road to Wigan Pier (London: Gollancz, 1937) 171. 6. OS, 8. 7. Barbara Greene, Too Late to Turn Back (London: Settle and Bendall, 1981) ix. 8. Graham Greene, Collected Essays (London: Bodley Head, 1969) 14. (Hereafter CE.) 9. Graham Greene, The Lawless Roads (London: Longmans, Green, 1939) 10. (Hereafter LR.) 10. Marie-Franc;oise Allain, The Other Man (London: Bodley Head, 1983) 25. (Hereafter OM). 11. SL, 46. 12. Ibid., 19, 18. 13. Michael Tracey, A Variety of Lives (London: Bodley Head, 1983) 4-7. 14. Peter Quennell, The Marble Foot (London: Collins, 1976) 15. 15. Claud Cockburn, Claud Cockburn Sums Up (London: Quartet, 1981) 19-21. 16. Ibid. 17. LR, 12. 18. Graham Greene, Ways of Escape (Toronto: Lester and Orpen Dennys, 1980) 62. (Hereafter WE.) 19. Graham Greene, Journey Without Maps (London: Heinemann, 1962) 11. (Hereafter JWM). 20. Christopher Isherwood, Foreword, in Edward Upward, The Railway Accident and Other Stories (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1972) 34. 21. Virginia Woolf, 'The Leaning Tower', in The Moment and Other Essays (NY: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1974) 128-54. 22. JWM, 4-10. 23. Cockburn, 21. 24. Ibid. 25. WE, 32. 26. Graham Greene, 'Analysis of a Journey', Spectator (September 27, 1935) 460. 27. Samuel Hynes, The Auden Generation (New York: Viking, 1977) 228. 28. ]WM, 87, 92. 29. Ibid., 272, 288, 278. -

Graham Greene and the Idea of Childhood

GRAHAM GREENE AND THE IDEA OF CHILDHOOD APPROVED: Major Professor /?. /V?. Minor Professor g.>. Director of the Department of English D ean of the Graduate School GRAHAM GREENE AND THE IDEA OF CHILDHOOD THESIS Presented, to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS By Martha Frances Bell, B. A. Denton, Texas June, 1966 TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page I. INTRODUCTION 1 II. FROM ROMANCE TO REALISM 12 III. FROM INNOCENCE TO EXPERIENCE 32 IV. FROM BOREDOM TO TERROR 47 V, FROM MELODRAMA TO TRAGEDY 54 VI. FROM SENTIMENT TO SUICIDE 73 VII. FROM SYMPATHY TO SAINTHOOD 97 VIII. CONCLUSION: FROM ORIGINAL SIN TO SALVATION 115 BIBLIOGRAPHY 121 ill CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION A .narked preoccupation with childhood is evident throughout the works of Graham Greene; it receives most obvious expression its his con- cern with the idea that the course of a man's life is determined during his early years, but many of his other obsessive themes, such as betray- al, pursuit, and failure, may be seen to have their roots in general types of experience 'which Green® evidently believes to be common to all children, Disappointments, in the form of "something hoped for not happening, something promised not fulfilled, something exciting turning • dull," * ar>d the forced recognition of the enormous gap between the ideal and the actual mark the transition from childhood to maturity for Greene, who has attempted to indicate in his fiction that great harm may be done by aclults who refuse to acknowledge that gap. -

Peter Hulme Graham Greene and Cuba

PETER HULME GRAHAM GREENE AND CUBA: OUR MAN IN HAVANA? Graham Greene’s novel Our Man in Havana was published on October 6, 1958. Seven days later Greene arrived in Havana with Carol Reed to arrange for the filming of the script of the novel, on which they had both been work- ing. Meanwhile, after his defeat of the summer offensive mounted by the Cuban dictator, Fulgencio Batista, in the mountains of eastern Cuba, just south of Bayamo, Fidel Castro had recently taken the military initiative: the day after Greene and Reed’s arrival on the island, Che Guevara reached Las Villas, moving westwards towards Havana. Six weeks later, on January 1, 1959, after Batista had fled the island, Castro and his Cuban Revolution took power. In April 1959 Greene and Reed were back in Havana with a film crew to film Our Man in Havana. The film was released in January 1960. A note at the beginning of the film says that it is “set before the recent revolution.” In terms of timing, Our Man in Havana could therefore hardly be more closely associated with the triumph of the Cuban Revolution. But is that association merely accidental, or does it involve any deeper implications? On the fifti- eth anniversary of novel, film, and Revolution, that seems a question worth investigating, not with a view to turning Our Man in Havana into a serious political novel, but rather to exploring the complexities of the genre of com- edy thriller and to bringing back into view some of the local contexts which might be less visible now than they were when the novel was published and the film released. -

Spy Culture and the Making of the Modern Intelligence Agency: from Richard Hannay to James Bond to Drone Warfare By

Spy Culture and the Making of the Modern Intelligence Agency: From Richard Hannay to James Bond to Drone Warfare by Matthew A. Bellamy A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (English Language and Literature) in the University of Michigan 2018 Dissertation Committee: Associate Professor Susan Najita, Chair Professor Daniel Hack Professor Mika Lavaque-Manty Associate Professor Andrea Zemgulys Matthew A. Bellamy [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0001-6914-8116 © Matthew A. Bellamy 2018 DEDICATION This dissertation is dedicated to all my students, from those in Jacksonville, Florida to those in Port-au-Prince, Haiti and Ann Arbor, Michigan. It is also dedicated to the friends and mentors who have been with me over the seven years of my graduate career. Especially to Charity and Charisse. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Dedication ii List of Figures v Abstract vi Chapter 1 Introduction: Espionage as the Loss of Agency 1 Methodology; or, Why Study Spy Fiction? 3 A Brief Overview of the Entwined Histories of Espionage as a Practice and Espionage as a Cultural Product 20 Chapter Outline: Chapters 2 and 3 31 Chapter Outline: Chapters 4, 5 and 6 40 Chapter 2 The Spy Agency as a Discursive Formation, Part 1: Conspiracy, Bureaucracy and the Espionage Mindset 52 The SPECTRE of the Many-Headed HYDRA: Conspiracy and the Public’s Experience of Spy Agencies 64 Writing in the Machine: Bureaucracy and Espionage 86 Chapter 3: The Spy Agency as a Discursive Formation, Part 2: Cruelty and Technophilia -

Graham Greene's Work in the Time of the Cold

Jihočeská univerzita v Českých Budějovicích Pedagogická fakulta Katedra anglistiky Bakalářská práce Graham Greene’s Work in the Time of the Cold War Vypracoval: František Linduška Vedoucí práce: PhDr. Alice Sukdolová, Ph.D. České Budějovice 2017 Prohlášení Prohlašuji, že svoji bakalářskou práci jsem vypracoval samostatně pouze s použitím pramenů a literatury uvedených v seznamu citované literatury. Prohlašuji, že v souladu s § 47b zákona č. 111/1998 Sb. v platném znění souhlasím se zveřejněním své bakalářské práce, a to v nezkrácené podobě – v úpravě vzniklé vypuštěním vyznačených částí archivovaných pedagogickou fakultou elektronickou cestou ve veřejně přístupné části databáze STAG provozované Jihočeskou univerzitou v Českých Budějovicích na jejích internetových stránkách, a to se zachováním mého autorského práva k odevzdanému textu této kvalifikační práce. Souhlasím dále s tím, aby toutéž elektronickou cestou byly v souladu s uvedeným ustanovením zákona č. 111/1998 Sb. zveřejněny posudky školitele a oponentů práce i záznam o průběhu a výsledku obhajoby kvalifikační práce. Rovněž souhlasím s porovnáním textu mé kvalifikační práce s databází kvalifikačních prací Theses.cz provozovanou Národním registrem vysokoškolských kvalifikačních prací a systémem na odhalování plagiátů. 11.7.2017 Podpis Poděkování Tímto bych chtěl poděkovat vedoucí této bakalářské práce PhDr. Alici Sukdolové, Ph.D. za odborné vedení, za pomoc a rady při zpracování všech údajů a v neposlední řadě i za trpělivost a ochotu, kterou mi v průběhu psaní této práce věnovala. Abstrakt Tato práce zkoumá vliv politického prostředí na tvorbu anglického prozaika Grahama Greena ve druhé polovině jeho tvůrčího života. Zaměří se na proměnu stylu psaní autora, psychologický a morální vývoj charakterů hlavních hrdinů a na celkovou charakteristiku Greenovy poetiky. -

An Oral History of the South Vietnamese Civilian Experience in the Vietnam War Leann Do the College of Wooster

The College of Wooster Libraries Open Works Senior Independent Study Theses 2012 Surviving War, Surviving Memory: An Oral History of the South Vietnamese Civilian Experience in the Vietnam War Leann Do The College of Wooster Follow this and additional works at: https://openworks.wooster.edu/independentstudy Part of the Oral History Commons, and the Social History Commons Recommended Citation Do, Leann, "Surviving War, Surviving Memory: An Oral History of the South Vietnamese Civilian Experience in the Vietnam War" (2012). Senior Independent Study Theses. Paper 3826. https://openworks.wooster.edu/independentstudy/3826 This Senior Independent Study Thesis Exemplar is brought to you by Open Works, a service of The oC llege of Wooster Libraries. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Independent Study Theses by an authorized administrator of Open Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. © Copyright 2012 Leann Do The College of Wooster Surviving War, Surviving Memory: An Oral History of the South Vietnamese Civilian Experience in the Vietnam War by Leann A. Do Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements of Senior Independent Study Supervised by Dr. Madonna Hettinger Department of History Spring 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements ii List of Figures iv Timeline v Maps vii Chapter One: Introduction 1 The Two Vietnams Chapter Two: Historiography of the Vietnam War 5 in American Scholarship Chapter Three: Theory and Methodology 15 of Oral History Chapter Four: “I’m an Ordinary Person” 30 A Husband and -

Framing 'The Other'. a Critical Review of Vietnam War Movies and Their Representation of Asians and Vietnamese.*

Framing ‘the Other’. A critical review of Vietnam war movies and their representation of Asians and Vietnamese.* John Kleinen W e W ere Soldiers (2002), depicting the first major clash between regular North-Vietnamese troops and U.S. troops at Ia Drang in Southern Vietnam over three days in November 1965, is the Vietnam War version of Saving Private Ryan and The Thin Red Line. Director, writer and producer, Randall Wallace, shows the viewer both American family values and dying soldiers. The movie is based on the book W e were soldiers once ... and young by the U.S. commander in the battle, retired Lieutenant General Harold G. Moore (a John Wayne- like performance by Mel Gibson).1 In the film, the U.S. troops have little idea of what they face, are overrun and suffer heavy casualties. The American GIs are seen fighting for their comrades, not their fatherland. This narrow patriotism is accompanied by a new theme: the respect for the victims ‘on the other side’. For the first time in the Hollywood tradition, we see fading shots of dying ‘VC’ and of their widows reading loved ones’ diaries. This is not because the filmmaker was emphasizing ‘love’ or ‘peace’ instead of ‘war’, but more importantly, Wallace seems to say, that war is noble. Ironically, the popular Vietnamese actor, Don Duong, who plays the communist commander Nguyen Huu An who led the Vietnamese People’s Army to victory, has been criticized at home for tarnishing the image of Vietnamese soldiers. Don Duong has appeared in several foreign films and numerous Vietnamese-made movies about the War.